Executive Summary

Financial advisors often have clients who are too busy to deal with many of the numerous tasks that are required of them by their financial plans, as their cognitive and/or emotional plates are filled by the issues that take priority in their daily lives. In these situations, advisors can use ‘nudges’ as decision-making aids that automate processes for clients, simplifying routine tasks and helping clients to sidestep potential struggles with willpower, rewarding them with quick results with minimal effort… which, in many instances, is exactly what clients want!

Yet, while nudges can be very useful tools for helping clients to take action, advisors who rely on using nudges with their clients – but who also want to educate their clients – may find themselves challenged to find opportunities to explain the larger reason of ‘why’ behind the financial plan. This is because the primary utility of nudges is often simply to help automate tasks, not necessarily to educate clients. In fact, nudges are often effective precisely because they bypass the parts of our brains that require conscious thought! But without getting educated on why they need to do what their financial plan says is important, clients may ultimately struggle with developing the resiliency and financial self-efficacy that can be crucial to staying the course prescribed by their financial plans in the long run.

However, the reality is that not all nudges are designed equally – there are some nudges that can still be used effectively when the advisor’s intent is to educate clients. There are two dimensions used to characterize nudges, which include Type and Transparency.

Nudge Type refers to the level of conscious thought required to carry out an action; it includes Type 1 nudges (involving automated processes and subconscious decision-making) and Type 2 nudges (involving deliberative action and conscious thought). Nudge transparency, on the other hand, refers to whether the intention behind the nudge is communicated and made clear to the client; the intention of a Transparent nudge is made clear to and is understood by the client, while a Non-Transparent is not.

The significance of understanding nudge types and transparency is that while advisors can effectively use Non-Transparent nudges to support their clients by automating simple tasks, it’s the Transparent nudges (whether they are Type 1 or Type 2) that still force at least some level of conscious thought about the nudge, thereby fulfilling the advisor’s objective to not just help clients change their behavior but educate clients so that they truly understand how their financial plan recommendations are, in point of fact, designed to support their financial goals!

Ultimately, the key point is that, by understanding the psychology behind different styles of nudges, advisors can use these tools to help their clients achieve their financial goals… and still help clients get educated and understand the ‘why’ behind their financial plans. As while some recommendations can be simply nudged to help clients take action with minimal thought and with little regard to the underlying processes (e.g., to set up monthly savings deposits), others necessitate clients learning and accepting the reasons for the things their financial plans require of them (e.g., to review and discuss potential portfolio allocation changes). And with the ability to discern not just when to implement nudges, but also which types of nudges to use, advisors can better match the approach to when clients just need help getting something done, and when there’s an opportunity for them to get better educated along the way (and build their financial resiliency and self-efficacy in the process)!

As financial advisors know, working with financial planning clients involves a lot of teaching. And teaching clients can be extremely rewarding because it often empowers clients to develop skills to take on larger tasks that ultimately help them realize important goals.

Yet sometimes, busy clients don’t always have the time nor the desire to learn the deeper nuances and theory behind their financial plan objectives – after all, many clients engage with their financial advisor precisely because they want to delegate and have someone else to think deeply about and take care of (and bear some responsibility for!?) these matters for them!

And so ‘nudges’ – decision-making aids designed to simplify the process for clients to stick to their financial plans (without them even needing to think about it!) – are often a convenient and easy tool that advisors can use to help clients (of course with their full understanding and acknowledgment of the nudge!) take action and implement important changes in a manner that requires minimal effort from the client… which, in many instances, is exactly what the client wants.

However, when it comes to the advisor’s objective of educating their clients, advisors may ask whether using nudges is really a good approach to help their clients. After all, if a client is ‘thoughtlessly’ nudged towards a particular outcome, they may do the right thing but will never get educated on the thing itself, leaving a knowledge void that means the client still may not be well prepared for the future!

Yet, in reality, recent research on how teachers are using choice architecture has suggested that using nudges can, in fact, be used to support learning without necessarily sidestepping it. Which means financial advisors, too, have the opportunity to nudge clients… and still maintain their underlying commitment to teaching them how to flourish as well!

How Nudges Help Form Good Habits But Can Undermine Good Learning

Nudges are designed to eliminate the requisite brainwork for simple or repetitive tasks so that clients – and even advisors – don’t have to remember or think about why they need to do something each time they need to do it; once a task has been deemed necessary, nudges are easy ways to put tasks on auto-pilot to ensure they get done with minimal effort, and without slipping through the cracks.

For example, if a client wants to save up for a vacation a year from now, their advisor may help them set up monthly auto-transfers to a separate “vacation account” that will stay in effect for the next year, instead of requiring the client to remember to set aside a growing portion of their primary checking account for their future vacation. This is an easy way for the advisor to help the client implement positive behavior that will help them achieve a specific financial goal. Nudges, in this way, make it easy for clients to ‘adopt’ the new savings habit and ultimately end up with enough to realize their goal of taking a vacation in a year.

Nudges Make It (Too?) Easy For Clients To ‘Adopt’ Simple Habits

The vacation savings example is simple and offers a great opportunity for nudges. However, is it possible that nudges might make things too easy?

As while there’s generally very little thinking involved when advisors use nudges to encourage behavior that they want their clients to adopt, are nudges really helping the client establish sustainable new behaviors if they haven’t even learned the ‘why’ in the first place?

Example 1: Cleo, a newer client, has come in to meet with her financial advisor, Addy, and stated that she has three main savings goals: 1) retirement, 2) remodeling her kitchen, and 3) her daughter’s upcoming wedding.

Cleo is currently saving through her company’s 401(k) plan, so Addy helps Cleo by determining how much Cleo needs to save to meet the remodel and wedding goals and sets up two new accounts to automatically pull funds for the kitchen and wedding.

Addy briefly reviews an estimated budget that Cleo has prepared to assess her spending and decides that Cleo can easily accommodate the extra savings on a month-to-month basis. When Addy asks Cleo to review and approve the proposed spending cuts, Cleo simply says, “With the help of these automatic savings transfers, I’m sure I’ll be able to adjust. These nudges should make stuff easy, right?”

For the first few months, everything worked out just fine. The accounts Addy set up for Cleo helped Cleo meet her savings goals. Yet, in the third month, Cleo called Addy to tell her that she just didn’t have enough money to ‘get along’.

Because Addy had not taken a deeper dive into the budget before establishing Cleo’s monthly savings plan, the nudges she implemented (automated transfers into the newly created accounts) simply created more problems.

Had Addy taken advantage of the teaching opportunity that reviewing Cleo’s budget more carefully had presented to her, both Addy and Cleo may have ended out with a much better understanding of Cleo’s actual spending habits and needs, which also might have led Addy to consider a less aggressive – and much more realistic – savings plan for Cleo.

From this perspective, while nudges may help clients comply with a prescriptive plan of action (e.g., to transfer money each month into a savings account), they may not actually help anyone to consciously adopt new behaviors (e.g., to learn new spending habits to sustain long-term savings goals).

Because without recognizing how and why you’re actually doing something (which is often the case with financial planning clients ‘nudged’ into action), how can new behaviors really stick… without being stuck forever relying on the nudge as a crutch?

In reality, though, the utility of nudges is unquestionably beneficial. Because who really takes the time to explain the psychology behind setting up default savings? If you do, that’s great! But even if you don’t (which is probably normally the case for most financial advisors), there is rarely any harm done to the client in helping them automate their savings.

The reason we love nudges so much is that they serve as quick and simple ways to help clients modify their behavior – we love them for “compliance” (how easy it is for the client to comply with the recommendation). Which is not a bad thing… because what advisor wouldn’t want to work with clients who listen to them and do the things they suggest the clients need to do?

For instance, many financial advisors may be familiar with programs like the Save More Tomorrow approach, devised by behavioral finance researchers Shlomo Benartzi and Richard Thaler, that involves employers arranging for their employees to be automatically enrolled in their 401(k) plans, and to have their savings contributions automatically increased gradually over time.

Employees in the program are often not even aware of being enrolled in their 401(k) plan because they may not understand (or simply don’t prioritize and have forgotten about) the benefit options and default elections they agreed to as a new hire when they joined the company in the first place. Thus, many employees may not even realize they can choose to opt out of these programs whenever they wish. They just let themselves get defaulted in and achieve the exact savings goal that was intended! Though at the same time, employees generally have little buy-in to the importance and value of saving… because they didn’t even realize or ‘choose’ to do so in the first place!

So even though nudges are meant to help employees do the ‘right’ thing by saving for retirement, they make it very easy (perhaps too easy) to the point that employees weren’t even aware of what was happening. Which isn’t bad, per se – because again, they are doing the right thing – but the nudges were not teaching the employees anything about the value of what they were doing nor about the impact that their actions would have on important long-term savings goals.

Nonetheless, programs like Save More Tomorrow have been wildly successful, mainly because they circumvent the challenges that employees face with self-control and willpower. Few people voluntarily exert self-control to curb spending when they don’t really need to (and thus may find it easy to put off saving for retirement and difficult to establish a savings habit in the first place), nor do they feel the need to struggle with limited willpower reserves (which is often the case when it comes to increasing annual retirement savings or manually enrolling themselves in their employer’s 401(k) plans). Accordingly, when programs do these things automatically for them, it can seem like magic! There’s no thinking, self-control, or willpower required. Savings just starts happening.

But the questions remain – What if they change jobs and there isn’t an automatic enrollment? What if the portfolio in which they are enrolled is actually inappropriate for them, given factors unknown to the organization? Will the client be able to cope in any environment that doesn’t perfectly set up the same nudge in the same way in the future?

In other words, nudges can perhaps be valuable tools used to encourage a client to do what they need to do to follow their financial plan, but is that all a good financial advisor really wants? What about educating their clients?

How Nudges Can Fail When It Comes To Educating Our Clients

From the perspective of education, it is clear that nudges quickly fall short. Education researchers point out that nudges are not necessarily great long-term solutions because they don’t actually teach anything; instead, the whole point is that nudges are designed to be short-term ‘unthinking’ solutions.

True financial planning mirrors this same concern. Whereas the Save More Tomorrow program may seem to be an effective tool to implement immediate client behavior changes, it isn’t really about ‘true’ financial planning… and neither is opening a bunch of automatic savings accounts.

While these actions can be important to the financial plan, they are not, in and of themselves, actually helping the client embrace the gestalt of their financial plan. For many advisors, doing financial planning involves not just getting the client to behave in a certain way but actually helping them understand financial rules and concepts, review financial scenarios, engage in financial discussion, and have buy-in and a commitment to the plan itself.

Another nudge concern coming from educators that also translates to planners is that nudges only focus on the end result; they don’t consider the resulting – and perhaps undesirable – processes or behaviors in the fallout.

For instance, nudge research shows that people are often motivated to work harder or comply with a certain behavior by hearing how other people, like their neighbors, have done. A number of studies have replicated the famous initial study by Costa and Kahn that showed how individuals would strive to reduce the use of electricity in their household once they learned that they were consuming more electricity than their neighbors!

What does this mean to a professor (or financial advisor who wants to educate their clients)? Simply because I can motivate my struggling students by telling them how they were doing in comparison to their classmates, does that mean it is the right way to help them improve their performance? Financial advisors face a similar question – comparing to others can be a powerful nudge, but does comparing their clients’ wealth accumulation to others really help motivate them in positive ways to stick to their financial plans?

Said another way, just because I can get the desired outcome (e.g., for me, a student who gets better grades in my class), does that mean it is okay to disregard the underlying process or processes that end out occurring to attain that outcome? Maybe my students study harder because they believe that doing better is possible once they learn how other students are doing. As a result, perhaps they ask other students for study tips to figure out ways to study more effectively. Alternatively, maybe they experience high levels of anxiety and endure negative self-talk to work themselves to the bone to do better? Or maybe they even decide to risk cheating for a good grade because they don’t want to feel like they’re underperforming their peers? These examples all result in the same outcome, a higher grade, but as an educator (and really, as a compassionate human being), only one of these processes leading to the outcome is acceptable.

Similarly, in financial planning, would advisors push a client to save more by telling them the average savings rates of other clients with the firm? What might this nudge drive the client to do in order to attempt to meet or exceed the average? While one possible outcome might involve the client sitting down with their spouse or advisor to set up a gradual savings program, what if, instead, the client starts a dramatic savings regimen by cutting out their vacations (and estranging themselves from their family) while also eliminating their health insurance (to save on premiums, since they feel they’re healthy anyway), which is not only is unsustainable beyond the short-term but also drastically drives down their overall life satisfaction and actually increases their risks?

Ultimately, both solutions result in meeting the same immediate short-term goal of more savings. Yet, only one does it in a healthy way. And because nudges are only designed (and measured) in terms of whether the outcome is successful or not, both solutions would technically be appropriate. And yet, only one of these solutions truly offers a viable (and desirable) long-term strategy. Furthermore, if the client were to save at a level that is unmanageable for them or just leaves them feeling broke, they probably wouldn’t continue for very long, anyway.

When it comes to teaching students, outcomes and the processes by which those outcomes are achieved both matter… yet again, with most nudges, only the outcome is taken into consideration.

Similarly, when it comes to financial planning, the processes that advisors use to help their clients reach certain outcomes are very important. If clients arrange to have everything done for them without ever really having to think about why certain things might be important, they may never have the opportunity to develop any resiliency or financial self-efficacy.

After all, while nudges are designed to prevent failure, failure itself can actually be key for educating clients about their financial planning needs and the importance of (sustainably) changing their behaviors.

For instance, research on the impact of nudges used in education looked at students who were not nudged and allowed to set their own study timelines. It found that while students were willing to create timelines for themselves, the absence of nudges actually led to suboptimal behavior – they did worse!

However, perhaps that same student learned from their initial failure and adjusted their long-term study timeline accordingly, such that by the end of the academic year, their study habits (and resulting final grades) were much better than the students who didn’t take the time to create their own timelines! A learned behavior of creating their own structure that will benefit them in a wide range of situations in the future!

Advisors who want to teach their clients about financial planning are generally similar to classroom educators. While we certainly don’t want our clients’ plans to ‘fail’, we also know that markets are going to fluctuate and disruptions (e.g., pandemics or financial crises) are going to happen, and these events may cause clients to feel like their plans are off track and failing. In some cases, these events may even require the client to implement certain behavior changes to get the plan back on track.

But the opportunity to learn from these moments of failure (or at least the threat of failure) can help clients develop resiliency through these stressful situations, which can be a powerful asset from a long-term perspective. As in the end, it is a lot easier to encourage clients to stay invested when market conditions go through a rough patch in the future if they have survived a previous patch and thrived after continuing to stay the course.

Simply put, learning lessons through failure can help clients bolster their resolve, identify new solutions, and build strength in the face of adversity. Additionally, supporting clients and guiding them through times of failure can help advisors develop more resilient and trusting relationships with their clients. Students remember when you coach them through a rough spot… and clients will, too.

A Two-Dimensional Framework For Nudges That Support Client Education

When designing nudges, there are often many aspects of learning that are not considered and even purposefully sidestepped. But that does not mean that nudges have no value, as there are different variations of nudges that can be used effectively for specific purposes, including to support educational/learning outcomes.

Nudges generally come in four variations with differences based on two specific criteria – Transparency and Type. Understanding more about each of the variations of nudges reveals that they can indeed be a useful tool in education and financial planning… beyond just helping clients get started with savings habits.

Nudge Transparency

The first criteria that distinguishes certain nudges involves assessing whether the nudge is either Transparent or Non-Transparent. Transparency here refers to the intention of the nudge – if the intention is made obvious to the client, then this is considered a Transparent nudge.

As a simple example, consider an advisor who directly asks their client to set a savings goal. Based on education research, the question alone – just asking someone to set their own goal – actually has the power to help the person realize their goal.

For instance, researchers examined procrastination and academic performance by comparing students who were simply being told what to do by their teacher versus students who were given the option to choose their own goals. Those who were given the opportunity to choose their own goal tended to perform better.

This study suggests that advisors who encourage clients to figure out a systematized saving approach that works for them and their current circumstances, versus advisors who simply instruct clients to set up automatic transfers to their savings accounts (based solely on a mix of financial calculations and common benchmarks with less consideration of life circumstances and personal choice), may have clients who are more successful in achieving their desired outcomes – sustained savings and spending habits over time.

One simple example of a non-transparent nudge is whether outcomes are framed as a loss or gain. Choosing the right framework to introduce a nudge can impact its effectiveness to encourage certain client behaviors, as original research done by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1981 showed that people tend to react differently when outcomes are framed either as a loss or gain, even when the outcome framed is actually the same.

Example 2: Cleo is in Addy’s office to re-visit Cleo’s budget, and they are now doing a deep dive on spending habits to see how much they can realistically set up.

Things are not going all that well – Addy is frustrated because for every suggestion she makes to help Cleo cut her spending, Cleo comes up with an excuse not to implement it.

Addy feels her blood pressure rising, and Cleo is just getting more and more defensive. Addy decides to call a break and suggests they ask Thomas, another advisor at the firm (who is very successful at helping his clients change their spending habits), to join them.

Thomas sits down and begins the conversation, “Let’s talk about a spending plan! Cleo, tell me about a typical week for you, and then tell me about a typical month. What do you like spending your money on the most?”

Cleo, surprised by the freedom to talk about how she likes to spend her money, begins to open up. The entire conversation begins to shift in a positive direction, and by sharing her feelings about her spending habits, Cleo comes to a deeper understanding of what she can realistically cut back on.

Can both approaches end up with the same outcome? Yes. Creating a spending plan (where will you spend in ways you enjoy) and creating a budget (how will you limit the spending in categories that are too much) are the same thing. Yet, framing the conversation more simply can go a long way. Herein lies the magic with the use of Transparent nudges.

In both approaches, the intention is the same (i.e., to find ways to save money). Cleo knows that her plan is giving her a way to move forward to reach her goals, yet Thomas’ Transparent nudge (engaging in a conversation that explored how Cleo enjoyed using her money and focusing on how managing her money can help her to spend more on the things she loves most), got traction over Addy’s non-Transparent nudge (recommending ways that Cleo could simply cut spending, without delving into how that savings would be used!). In the end, getting the client on board was all a matter of using the appropriate framing.

Nudge Type

The second criteria that characterizes nudges is referred to as Type. Nudges are either Type 1 or Type 2. Type 1 and Type 2 nudges follow from the two systems that simultaneously control our brains: System 1 (which involves automatic/subconscious thought processes) and System 2 (which involves deliberative/conscious thinking). Thus, Type 1 nudges result in subconscious decision-making, while Type 2 nudges engage the logical and rational portion of our brains and rely on deliberate choice and action.

An example of a Type 1 (automatic/subconscious) nudge is implementing automatic contributions made to 401(k) plans or savings accounts. As pointed out earlier, these nudges require no thinking and no willpower on behalf of the client. These programs are great tools when we want to sidestep willpower, such as when an individual is experiencing a high cognitive load and may be too busy (or distracted) to take on additional routine tasks.

Importantly, Type 1 nudges are not going to be appropriate to use all the time (or you would have a really, really tired client). For instance, as discussed earlier, when the goal is to educate the client for the long haul, Type 1 nudges won’t be the best tool to help your client understand the reasoning behind what they need to do to stick to their financial plan.

However, Type 1 nudges can be quite valuable during the first few meetings with new clients simply to help them get set up and started on the initial steps of their financial planning journey. Any time the advisor can automate and take a few things off of a busy person’s plate (which again won’t be all time) can be tremendously helpful and worthwhile for clients.

For instance, if you remove the thinking and stress about transferring sums of money for different savings goals, then the client may be free to concentrate on other areas of their financial plan. This can be especially helpful when Type 1 nudges address tasks that don’t require much thoughtful consideration so that the client can focus on areas that do require more contemplation.

Type 2 (deliberative/conscious) nudges rely on the client working through and actually thinking about their choices and actions. A good example of a Type 2 nudge in financial planning is an annual rebalancing policy that the advisor reviews with clients. An annual rebalancing policy constitutes a Type 2 nudge because, in essence, it requires the client to consider (and question or agree to) guardrail rules the advisor is proposing that relate to the management of the client’s portfolio (which in the future, will then happen ‘automatically’ as nudges that keep the client on track). In these meetings setting the nudges, though, the advisor has the opportunity to teach and engage in active discussion with their clients in order to set what the guardrail/nudges will be in the future.

Using Transparent Nudges To Help And Also Educate Clients

The system of characterizing nudges across the two dimensions of intention (i.e., Transparency) and the level of conscious thinking (i.e., Type) offer a framework to consider how nudges can be employed in financial planning across different scenarios, requiring different levels of transparency and thought, beyond just auto-enrollments and automatic savings plans.

As while simple Non-Transparent Type 1 nudges (e.g., Save More Tomorrow and similar automated-savings strategies) can be useful, they aren’t necessarily the only type of nudge available for advisors to use with clients, especially when we consider the larger underlying goals of financial planning like financial education and financial self-efficacy.

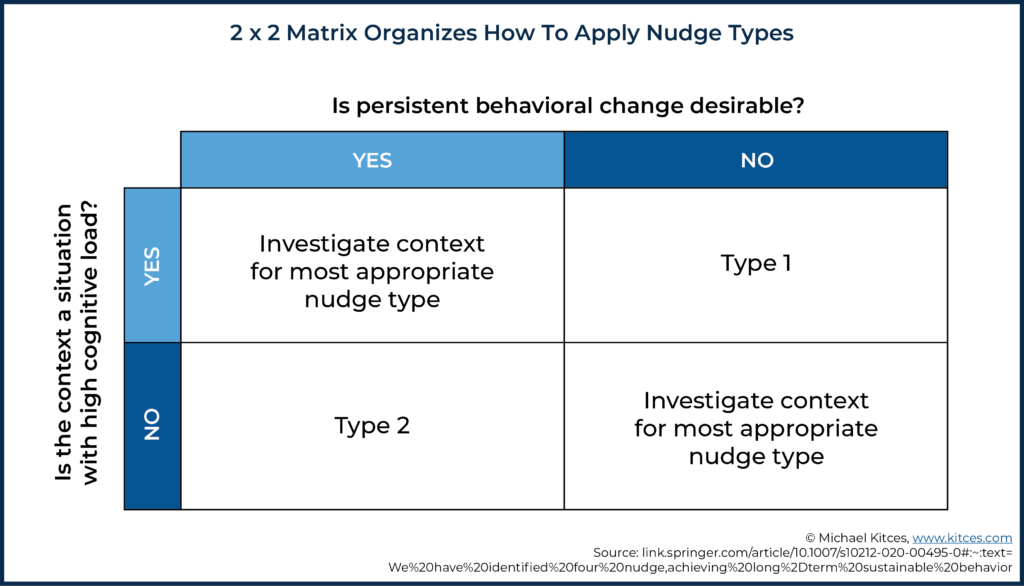

In particular, when it comes to educating clients, it is critical to make use of Transparent nudges (versus Non-Transparent nudges that fail to identify the intention of the nudge). To choose which Type of Transparent nudge to use with clients, advisors can refer to a simple 2x2 nudge matrix that shows how nudge Types can be applied in different situations.

This matrix was initially developed by Public Policy researchers Pelle Guldborg Hansen and Andreas Maaloe Jespersen, and was further refined by researchers Robert Weijers, Bjorn B. de Koning, and Fred Paas for use in education, which can also be easily applied to financial planning.

In order to use the matrix, one must consider two high-level questions:

- Is the individual experiencing a high cognitive load (i.e., the individual has little or no available mental bandwidth)?

- Is the behavior change we are trying to make a one-time change, or is this about changing some behavior permanently over time?

The answers to these questions can help financial advisors figure out which nudge Type they may want to consider using to help their client.

Type 1 Nudges Require Minimal Effort But Still Facilitate Educating Clients

Type 1 nudges are good to use during times when the client is experiencing a high cognitive load or perhaps emotional strain. Transparent Type 1 nudges require little thought, and their purpose is clear.

In financial planning, these nudges work well to encourage clients to make an upfront commitment to follow a particular strategy, which lowers the problem of struggling with insufficient willpower in the future. For example, an Investment Policy Statement is actually a form of pre-commitment strategy that constitutes a Transparent Type 1 nudge.

After all, Investment Policy Statements often have rules about when the advisor will rebalance the portfolio, such as when the target allocation in any given asset class is off by more than 10% of its desired allocation. Clients and their advisors discuss the agreement in the investment policy statement. Once the client understands the IPS guidelines, they sign the policy to acknowledge their agreement (even though it is not a legally binding document, it’s still a positive affirmation of the commitment), understanding that they will be notified of when the advisory firm is making a change to their portfolio (within the parameters of the IPS). And because clients pre-committed to the strategy, they will be more likely to agree with the actions the advisor must take when the time comes, without getting hung up on any particular matter such as taxes or market volatility.

Pre-commitments nudge clients by reducing the amount of willpower they will potentially need in the future. Thus, Transparent Type 1 nudges can be most effective when advisors want to educate their clients, but also to simplify processes and reduce the legwork (and willpower!) required of clients to take action on their plans.

Type 2 Nudges Encourage Clients To Make Thoughtful Decisions

The goal of the Transparent Type 2 Nudge is clear: we are trying to educate the client from the start by helping them think about their decisions and consciously engage in deliberative decision-making in arriving at the system they will then implement to make their own decisions easier in the future.

Using a Transparent Type 2 nudge, advisors can focus on helping the client reflect on their situation, set their own personal goals, and build processes that work towards those goals. Again, we know that by setting our own goals and committing to a program that we think can work for us personally, we can actually realize greater productivity. Accordingly, by guiding clients to actively contemplate the importance of their goals and to understand why certain actions are required to execute their financial plans, advisors can motivate clients to successfully stick to their plans.

Moreover, while it may sound simple to ask the client about their goals, giving the client the opportunity to set and define their goals can be a powerful exercise that often ends out as a very meaningful and insightful process for them to crystalize the ‘why’ behind their financial plans!

Example 3: Think back to Cleo, Addy’s client, in the earlier examples. Another approach that may have been helpful for Cleo to develop a savings plan for her goals may have been for Addy to engage her in a conversation, encouraging her to provide greater details about her future kitchen and daughter’s wedding.

While Cleo had identified those goals, Addy never took time to explore them with Cleo, nor did she give Cleo much opportunity to embellish her ideas with details.

Thus, there was no emotional activation through a personal connection to Cleo’s goals to motivate her to create a plan for those goals, even though Addy had identified how important they were to Cleo.

Whereas if Cleo took 10 minutes to talk through each goal – actively visualizing the new kitchen and walking her daughter down the aisle – the emotional engagement would actually have helped inspire Cleo to take the necessary steps to make that emotional vision a reality!

In terms of clearing the way for important goals, Transparent Type 2 nudges are excellent tools to incorporate education and to engage the client in the process. Because by encouraging clients to consciously engage in and understand the ‘why’ behind their financial plans, advisors empower the client to aspire to financial self-efficacy.

Accordingly, advisors can implement Transparent Type 2 nudges by engaging clients in deeper, fact-gathering conversations about their goals, providing regular check-ins through meetings and phone calls to let the client know how they are doing, and by acknowledging and celebrating their progress.

There’s a lot more to nudging clients than setting up automatic savings plans for them. Advisors can use the psychology behind nudges to support clients, being sensitive to their stress or emotional state; at the same time, they can use nudges as opportunities to educate their clients about the ‘why’ of their financial plans and to motivate them to stick to their plans!

Moreover, while all nudges are generally designed to make things easier for clients, not all are conducive to teaching clients why they need to do the things their financial plans require of them. Accordingly, when considering which style of nudge to use, the golden rule is to use Transparent nudges when the goal is to educate clients and to consider process – not just outcomes.

Because financial planning clients approach their goals from a wide range of circumstances, it’s not always feasible or practical to make every recommendation an educational lesson. However, by understanding when it would be valuable to educate the client about a certain action needed, and when simply automating tasks for clients would be most helpful, advisors can use an appropriate nudge strategy to offer the most benefit for their client’s financial goals by taking their unique needs into account!