Executive Summary

Survivorship Guilt is the experience of emotional distress that can result after having survived a traumatic event when others did not. These feelings can have an adverse effect on behavior, such as reduced motivation and irritability, and when left untreated, can manifest in much more serious and harmful behaviors, including suicide. Given the trauma and tragedy that people have experienced because of COVID-19 around the world, Survivorship Guilt is unsurprisingly on the rise.

The nature of the K-shaped recovery from the pandemic (i.e., how certain parts of the economy have started to recover when others have not, or continue to get even worse) has faced financial advisors with clients who may be experiencing their own form of financial Survivorship Guilt, where they may be financially ‘okay’ (or possibly even better off than they were before the pandemic), but who feel ashamed or guilty for being okay as they witness (and empathize with) others suffering extreme hardship. These feelings of discomfort may cause their clients to do things with their money they would not normally do, and that may not be in alignment with their overall financial goals. For instance, clients with financial Survivorship Guilt may feel uncomfortable about the idea of enjoying or spending money, which manifests in unusual spending habits or even emerges as suddenly-drastic charitable giving. Thus, advisors will want to be on the lookout for signs of financial Survivorship Guilt in clients as COVID-19 continues to take its toll.

Given the financial advisors’ position in their client’s lives, they may be the first people to see or recognize these issues arising. Clients may indicate that they’re feeling guilty, ashamed, or disgusted because of their wealth, or they may lament the dramatic disparity that exists between the wealthy and the poor. Fortunately, though, for advisors who suspect that clients may be experiencing financial Survivorship Guilt, there are some things they can do to help.

First, advisors can highlight the benefit of and normalize the grieving process for clients with unresolved grief. While the pandemic has interfered with the traditional ways many of us normally grieve, grieving is still an essential part of healing, and failing to bring closure to the process can cause individuals to reconcile unresolved feelings by shifting their emotions to guilt and shame. Second, advisors who have clients that are philanthropically inclined and who want to use giving as a way to process grief can ensure that they give responsibly and in ways that have personal meaning for them. Third, advisors can encourage clients to group together (virtually if need be) for social support, perhaps through a giving drive where they can share stories of their grief, talk about their giving goals, or maybe to listen to a speaker on a topic of interest (e.g., Survivorship Guilt, philanthropy, etc.). Ultimately, the key point is that advisors have tools to help clients who may be suffering from financial Survivorship Guilt cope in healthy ways. By watching for signs of shame and guilt, advisors can recognize when their clients may need support, whether from the advisor directly or where appropriate via a mental health professional. Importantly, advisors must also recognize the critical importance to take good care of themselves too, both physically and emotionally, during these difficult times, which can only help them to serve their clients even better!

Survivorship Guilt Combines Surviving Trauma, Feeling Emotional Empathy, And Being Unable To Grieve

Survivorship Guilt is experienced when, after surviving a traumatic event such as an accident, serious illness, or war, a person feels guilty or shameful instead of happy, relieved, or grateful. These feelings can arise because of the fact that others were not so fortunate, for whom we feel empathy. And when we feel Survivorship Guilt for prolonged periods, it can be bad for our health, leading to irritability, a lack of motivation, and depression. Left untreated, unresolved guilt and shame can lead to even more serious mental conditions which may require special review and special treatment.

Importantly, though, trauma and traumatic events don’t necessarily have to involve one-time acute events such as accidents, war, or terrible illnesses. Even though these are the types of situations that may come to mind, trauma can actually mean a host of different things. For example, trauma can be created by smaller and/or chronically occurring events that happen over a long period of time. In the case of COVID-19, the long-standing effects pervaded nearly everyone’s daily life; while some individuals may not have personally known anyone who was adversely impacted, the reality of worldwide suffering has created an inescapable source of chronic trauma experienced by nearly everyone.

In addition to experiencing trauma, Survivorship Guilt also involves emotional empathy, as feelings of guilt often arise because of our capacity to empathize with others. It is because of empathy that we may experience the pain, fear, and suffering of others, even if we, ourselves, are not actually experiencing the source of pain first-hand. For instance, a study by Michael Poulin and Roxane Silver examined Survivorship Guilt as a result of the 9/11 attacks. Their study found that individuals who felt they had near-miss experiences connected to the attack had a higher chance of experiencing Survivorship Guilt. Which suggests that, given the worldwide impact that the pandemic has had on millions of people and the vast number of individuals who undoubtedly feel they may have narrowly escaped being affected by the virus, many people may be suffering from Survivorship Guilt as a result of COVID-19.

In addition to surviving trauma and emotional empathy, Survivorship Guilt can also involve a broken grieving process. Grief is a terrible feeling and no one likes to experience it. Nevertheless, grief is a crucial part of the healing process when we have suffered the loss of something important to us. And so it is important to grieve to acknowledge our pain and loss in order to eventually feel better.

Yet, because of COVID, many of us haven’t been able to grieve in the same ways we have traditionally grieved in the past. For instance, maybe with the passing of a loved one or friend, a person would have been able to grieve by attending a funeral, sitting shiva, or bringing over food. But because of COVID and social distancing requirements, many of these activities were not possible. As a result, there can be a lack of closure that may be subconsciously reconciled by feelings of guilt and shame. And so in lieu of grieving, people may end up with Survivorship Guilt, unable to process their grief.

Understandably, in these turbulent times, financial advisors may be witnessing more financial trauma as a very real issue experienced by many clients as they worry about their money. And as a result, they may suffer from financial Survivorship Guilt because of financial hardships they have personally experienced and since recovered from (even as they know or have seen others experience similar troubles and not fared so well in the aftermath).

For example, we can imagine (or perhaps remember) how awful the US housing market disaster felt – a somewhat acute traumatic event when people were losing their jobs and defaulting on mortgages as a result of extreme financial turmoil in the world. Clients who made it through okay may have suffered (or may still be suffering) from financial Survivorship Guilt, having known and empathized with their friends or family that did not fare as well.

The key point, though, is that given the traumatic impact of and tragic outcomes caused by COVID-19, financial advisors may have clients who have fared relatively well through these times and are feeling affected by Survivorship Guilt. So how can advisors recognize these clients, and what can they do to help them cope?

K-Shaped Recoveries May Find More Individuals With Financial Survivorship Guilt

COVID-19 has presented us with a unique situation because of the nature of its K-shaped recovery process, whereby certain parts of the economy (or socioeconomic classes) have started to or fully recovered, and yet others have not, or continue to get worse. Because of the unbalanced nature of the economy recovering, workers with white-collar jobs (who have benefitted more from the recovery) are disproportionately more likely to be experiencing financial Survivorship Guilt right now – as their jobs have returned (or perhaps were never in jeopardy), while many less fortunate workers were laid off and may still be unemployed. New research and articles have even alluded to the idea that privilege may be its own vice when it comes to financial Survivorship Guilt experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In fact, even for those whose economic security may not have been jeopardized, COVID still presented them (and everyone else) with traumatic experiences of death, illness, and financial strife everywhere, with little (if anything) that could be done about it. Thus, as was the case with the 9/11 attacks, even though we may not have been directly impacted by the sources of trauma, the people who were impacted – be they family, friends, or total strangers – kept increasing in number, in step with the emotional toll resulting from empathizing with those suffering hardship.

Importantly, first-hand experience of trauma isn’t a requirement to develop Survivorship Guilt; when the news and social media are serving as constant reminders of all the ways that different classes of individuals are being negatively impacted by the fallout (physically, mentally, and financially), it can be extremely difficult to feel grateful for weathering the storm just fine. Conversely, though, it also becomes easier to feel guilty when empathizing and grieving for others less fortunate.

How Financial Survivorship Guilt Can Hurt Clients

Because of the important roles that money and financial security play in the lives of financial planning clients (and advisors!), there are a number of ways that financial Survivorship Guilt can be hazardous.

For instance, financial Survivorship Guilt may lead to irrational money beliefs and behaviors (guilt around money, wanting to give away more than usual, discomfort spending money when others have so little to spend, etc.) as clients try to cope with feelings of guilt and shame that can come up.

Yet while experiencing a little Survivorship Guilt is probably not harmful – certainly philanthropic giving can be a wonderful way to connect and help others – some clients who may normally tend to be easygoing and generally unworried might just seem a bit more irritable these days (especially when meeting with their advisors over the very financial wealth that may be driving their guilt). Or some clients who are usually very motivated may suddenly seem to have difficulty taking action on their financial plans or may feel overwhelmed by what is going on, despite the fact that they, themselves, are financially okay and may be relatively unimpacted personally.

However, unless clients have experienced some sort of trauma and have seen a mental health provider to deal with that trauma, chances are they do not know why they are experiencing inner turmoil to begin with, not to mention that what they are experiencing has a name (i.e., Survivorship Guilt). More importantly, they don’t understand that these feelings can potentially interfere with good decision-making behavior, or what to do about it.

How To Help Clients With Financial Survivorship Guilt

Financial advisors certainly help clients to protect and grow their wealth, but ideally can also help clients enjoy their wealth. Therefore, if clients are having mixed emotions – or maybe even straight-up negative emotions – about simply being financially okay and safe in the aftermath of the pandemic, it is important for advisors to know how to recognize and address the situation.

If advisors can recognize when clients are experiencing financial Survivorship Guilt, then they can better strategize with clients to help them get back on track and enjoy their wealth. For example, if philanthropy is how clients want to address their emotions, advisors can assist them in developing responsible and appropriate giving strategies. Yet, for clients with extreme Survivorship Guilt (or any emotional hardship) that is making daily living difficult for them, advisors should know how to guide them to find appropriate mental health support.

Recognizing When Clients Have Financial Survivorship Guilt

The first step in helping clients with Financial Survivorship Guilt is simply to recognize it. If you have heard clients say any of the following, it’s a potential sign that they may be suffering from financial Survivorship Guilt:

“This whole situation is just so awful. I feel guilty that I am not doing more to help.”

“I don’t have the energy to get this stuff done right now. I was excited about this investment/opportunity before, but now…with everything that’s happening… it just feels wrong and uncomfortable.”

“I feel guilty that I have not been financially impacted to any great extent during COVID when I know so many others – even my own employees – have had, and continue to have, so many issues.”

“I am glad that I am okay and I know I worked hard during these times to be able to thrive a bit, but it still makes me feel sick and, in some ways, guilty to think about others who probably worked just as hard, if not harder, but who are not okay.”

“I want to give away more money this year. Given all that has happened and the fact that I am okay is great, but I also feel called to help. I can’t just sit back when so many people lost everything.”

Advisors can detect clients who may be suffering from financial Survivorship Guilt by paying special attention to the particular words that a client may be using. If they express guilt and shame, or that they are somehow suddenly feeling ‘wrong’ or discontent with their financial situation (even though their situation may not be much different than it was pre-COVID), they may be experiencing the effects of financial Survivorship Guilt.

In addition to telltale statements like the ones above, advisors may also detect certain uncharacteristic behaviors that may be signs of further problems coming down the road. For example, clients who are generally motivated and on top of things may suddenly seem unresponsive and unmotivated. Clients who are generally energetic and enthusiastic about new ideas may seem as if they are slowing down, sometimes even dramatically, and reluctant to take on new activity when experiencing Survivorship Guilt.

Irritability may also arise in clients experiencing financial Survivorship Guilt. For instance, if the client feels shameful or guilty, they might react with irritability when faced with next steps or new suggestions in their financial plan. A client who had expressed interest in acquiring investment property might snap at their financial advisor bringing up the recent dip in mortgage rates that should be a positive, telling them, “I have other things to worry about, we are in a pandemic! This extra property is the least of my concerns!” This may simply be a sign that the client is having some emotional turmoil that likely involves financial Survivorship Guilt.

Grieving, Giving, And Grouping: The 3 Gs Of Helping Clients With Financial Survivorship Guilt

For advisors who think they might be witnessing a client struggling with financial Survivorship Guilt, the most important thing to know is that there are things they can do to help the client. Three very useful techniques that can help struggling clients cope with their Survivorship Guilt involve grieving, giving, and grouping.

And notably, while these techniques can be especially useful and helpful with clients experiencing financial Survivorship Guilt, the advisor does not need to do anything special to confirm that financial Survivorship Guilt is the root of the problem, because these techniques can still be beneficial for clients if there are other reasons for their distress!

Supporting Grieving Clients

Many clients who have lost someone close to them (or may know someone who has lost someone dear) may have had their ability to properly grieve compromised. Gathering to mourn with family and friends is an important part of the grieving process for many, but for many has been curtailed because of the global impact of COVID-19 and its social distancing requirements.

Furthermore, when the need to grieve for loss and trauma exists on a worldwide scale, as has been the case with the millions of lives taken by COVID, it is often very difficult to specifically identify the loss and be able to feel a finite sense of closure for what has been lost. The ambiguous loss that results compounds the difficult grieving process, as grief tends to come more naturally when something has truly come to an end (while for so many, COVID-19 has been the disruption that just lingers on and on!).

Accordingly, as a way to reconcile this broken grieving process, some people may subconsciously turn to Survivorship Guilt as an outlet for unresolved emotions. And because guilt can feel like a safer emotion than grief when everything feels so turbulent and overwhelming, this can be a workable alternative (at least on a short-term basis). However, it doesn’t change the fact that to truly heal from a traumatic experience, individuals must eventually grieve. Covering it up or replacing it with feelings of guilt or shame may actually leave someone in a worse state and, again, prone to maladaptive (and even harmful) thinking and behavior.

Moreover, if you know a client has lost someone close to them, or if you know that they are manifesting their survival as shame and guilt when others have died, it can help to suggest the healing power of grieving and its importance, as clients might not even realize they are avoiding the grief process.

Example 1: Clara is meeting with her financial advisor, Adam, after having just lost a good friend of hers to COVID-19. Through their conversation, Adam recognizes that Clara may be suffering from Survivorship Guilt. Adam uses his own situation to highlight the value that grieving can offer.

Clara: I just feel overwhelmed, like this is never going to stop. I have lost a close friend. Things will never be normal again and I feel so uneasy and I just don’t know what to do.

Adam: Thank you for sharing with me how you are feeling. I value your honesty and openness. If I may, would it be alright if I share with you something personal that has helped me?

Clara: Sure, anything.

Adam: I too have lost close friends. And I do still feel unsettled by all of this. Yet, one thing I have actively started to do is to allow myself to miss them – to grieve for my friends and loved ones.

I know that might sound a bit odd, and I don’t mean to suggest that you do not miss your friend. It is just that, during COVID and all this mess, I normally would have been able to attend a funeral, visit my friends’ homes, and spend time talking about my memories with them. I’ve come to realize how important those things are, and that although I can’t do those things in the same way right now, I can still find ways to create that connection.

For example, I have called other friends just to reminisce about our lost friend, I’ve sent food to their family, and I have started just to think about them more – those ideas may or may not work for you, but just taking a little time to actively think about how to grieve… that has helped me.

Clara: Yes, you make a good point. My friend that I lost… I remember getting the phone call when I learned that she was gone, but then I couldn’t do anything. The fact that I didn’t do anything has festered. But… perhaps I can still call my other friends who also knew her. Maybe I will.

In the above example, the advisor didn’t suggest that the client had failed in any way by not addressing their grief. Instead, once the client had shared what they were feeling, the advisor took the opportunity to normalize how the current environment can prevent us from resolving our grief through traditional means (e.g., attending a funeral, gathering with friends, etc.).

Accordingly, the key is not to give instructions and say, “You should go grieve!” Instead, the advisor pointed out how grieving had helped them – never pushing the client to grieve, accusing them of not grieving, or even trying to rationalize the stress, guilt, or shame as resulting emotions from a lack of grieving.

The most effective way to help clients grieve is simply to normalize how difficult COVID has made it to observe traditional ways of resolving grief. And yet, as difficult as it may be to do things traditionally, there are unconventional ways that are beneficial that still allow us to process our grief.

Guide Clients By Developing Responsible Giving Strategies

Another great way to address the shame and guilt that come specifically from financial Survivorship Guilt is through philanthropy. Giving feels good; whether individuals give their time or dollars, giving can benefit not only the donor but also those who may benefit (directly or indirectly) from the donation made. And there are so many different ways to give – individuals can choose to contribute to whichever charity or movement makes the most sense to them.

Financial advisors can help their philanthropic clients make gifts using strategies that are sensible and healthy. For clients who wish to process their grief through an act of giving, advisors can pay special attention to find ways to connect the giving with the client’s source of grief or shame, in a meaningful way that can help the client process their grief, yet while making sure that clients aren’t giving mindlessly.

Importantly, though, the point is not to encourage clients to give as a way to assuage any potential guilt. The client must be open and willing to making the gift to the charity/organization of their choosing and of their own volition. They must also understand that they are in no way obligated to give as a means to rectifying their guilt. It is simply a pathway for those who are already inclined to do so… and one that advisors can help clients shape productively.

Example 2: Clara is meeting with her financial advisor, Adam, again to discuss how she is still feeling overwhelmed by her friend’s death. She has talked to some friends, but still wants to do something more. Adam has the following conversation with her to see if giving might be a suitable option.

Clara: I just feel ‘wrong’ for being okay. There are so many people out there hurting, I feel guilty for being here able to discuss my options. The fact that I have options feels shameful.

Adam: I really appreciate that you are opening up and sharing how you are doing emotionally. If I am hearing you correctly, and correct me if I am not, guilt and shame are really tough emotions that you’re feeling right now. Is it fair to say that the idea of feeling okay does not feel okay?

Clara: Yes. Exactly. Feeling okay has me feeling like a jerk.

Adam: Well, let’s explore a bit more about that, as you say, feeling like a jerk. Tell me, is there something that you think you could do that would make you feel like less of a jerk?

Clara: Actually yes, I was just listening to the news about how women have been adversely impacted by COVID-19. My friend that I lost, before losing her to COVID she did lose her job, and well, maybe I can help do something there… you know, for other women who have been adversely impacted by this situation.

Adam: Perfect. Let me do a bit of research and see if I can find a qualified charity that supports that cause. If I find a charity that appeals to you and that you want to give to, we will make it happen. Thanks again for sharing, letting me in on how you are doing – I am glad we are going to be able to connect ‘feeling not okay about being okay’ to something positive.

In the above dialogue, the advisor took the time to stop and address the client’s emotional turmoil. It may seem small, but the fact is that a lot of people feel that it’s ‘not okay to be okay’ right now. Yet, that does not mean we just have to live like that and accept feeling awful. Instead, we can take action and do something to resolve those feelings. And for some, that can mean finding ways to give. Advisors can assist clients to take back some control and feel better by making a meaningful difference.

Helping Clients Connect By Encouraging Group Bonding

Shame, guilt, grief, stress, and fear are all emotions that we often tend to handle more adeptly with someone by our side. As humans, we often feel an innate need to connect with others in groups when we experience these painful feelings. It is human to want to share our feelings and experiences; we often feel a sense of satisfaction and belonging not only when we are able to help alleviate another person’s burdens, but also when others are available and willing to help us with our own. And this is especially important now, given how COVID-19 has wildly disrupted our ability to connect with others.

With this in mind, advisors can support their clients not just by helping them manage their financial affairs, but also by encouraging group bonding beyond the confines of one-on-one meetings between just the advisor and client.

For instance, if advisors find that a number of their clients want to give, they may find their clients are really excited about participating in a group-based giving drive with each other. This might be organized simply by having a “Giving Night” (perhaps modeled as a socially-themed fundraiser) or group Zoom conference pitched as a “Giving Get-Together” with an invited speaker (which can even be the advisor themselves) discussing the value of giving and getting together in times like these.

Attendees can be encouraged to talk about gratitude and to share stories about how they are managing (or perhaps even not managing). Advisors have built-in networks in their own client bases, and when they are brought together for positive connections, something really special may bloom!

When Clients Need A Mental Health Professional

Importantly, advisors should recognize that some clients may be adversely impacted by feelings of Survivorship Guilt to the extent that they need professional mental health support. In those instances, it will benefit both the advisor and the client for the client to consider seeking help. Importantly, advisors can remind clients that mental health professionals are excellent resources for clients (and advisors) who need their support, and are no less important than seeking help from a CPA or an estate attorney.

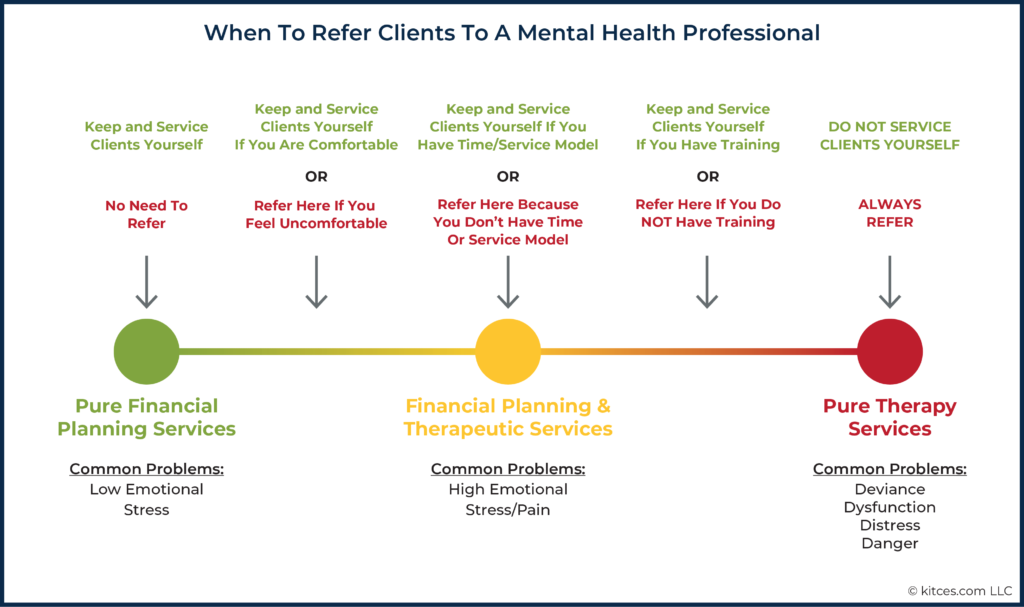

Referrals to mental health care professionals should always be made when the client has a problem that appears to be a condition that would be psychologically diagnosable (e.g., addiction, clinical depression, hoarding behaviors). Advisors can watch out for new behaviors that are described by the four “D’s”, which can signal a potentially diagnosable problem: Deviance (does the client’s behavior suddenly seem inappropriate or socially unacceptable?), Dysfunction (does the client seem to have trouble relating to others and/or thinking clearly?), Distress (is the client expressing unusual signs of stress or pain?), and Danger (are there any signs that the client may pose a danger to themselves?).

However, when the issue is not as clear cut and the client’s condition isn’t obviously diagnosable, a general rule of thumb advisors can use would be to consider referrals based on the advisor’s comfort level and ability to service the client’s needs. If they feel uncomfortable working with the client because the intensity of the client’s emotional stress or pain is too high, or because they do not have the time or service model to accommodate the level of financial therapeutic services the client needs, it would behoove both the client and advisor to refer the client to a mental health professional.

Importantly, giving a mental health referral is much easier and simpler than it sounds. The key is to normalize the idea so there’s less chance of any stigma being associated with the prospect of visiting a mental health professional. As such, if you haven’t yet brought up the fact that your firm can also make mental health referrals in the same way it makes referrals to CPAs and estate attorneys – get started today! Consider having a mental health practitioner host your Giving Night, and introduce the idea that these professionals are valuable and totally normal.

Self-Care For Advisors Experiencing Survivorship Guilt

While every advisor’s attention is focused primarily on their clients, it is especially important for them not to forget about their own needs and to take time to recognize their limits. Advisors love their clients, and it can be hard for them to watch clients who feel hurt and not be able to help.

Yet, advisors also need to remember that emotional burnout, let alone general burnout, is a very real thing that can adversely affect their happiness and quality of life. Moreover, given that the financial advisory industry has actually fared remarkably well through the pandemic, with most advisory firms still growing significantly in 2020 (if only thanks to the bull market that ensued), financial advisors themselves are especially likely to be on the upper side of the K-shaped recovery, and may be facing financial Survivorship Guilt themselves.

Ultimately, clients and their advisors themselves deserve to feel okay about being okay. In times like this, though, this can be a lot easier said than done. While financial Survivorship Guilt may be on the rise, advisors can help clients through the process of resolving these emotions… by bringing something better to themselves (peace of mind, relationships, support) and to the world around them (giving and grouping). You won’t be much good for your clients if you are not taking care of yourself.

Financial advisors provide immense value to clients when they actively work to connect their mental and financial well-being. Which in today’s environment means helping many clients who may be struggling to some extent with feelings of Financial Survivorship Guilt.

Fortunately, though, advisors are not without armaments. Advisors can remind clients to grieve. And advisors can help clients to give and group. Sometimes when we feel awful the obvious is not obvious to us, so help clients get the support that they need – and don’t hesitate to reach out to (and normalize working with) a mental health professional and bring them into the fold as well.

And while you are at it, be good to yourself too!

Leave a Reply