Executive Summary

Sometimes it can be easy to misconstrue financial planning as a purely logical industry, as clear-cut as analyzing the numbers, adding expertise, and then giving clients the requisite recommendations. However, as all advisors quickly learn in the field, personal finance is often more personal than it is finance. The emotional ties that people have to money understandably manifest in many ways, and figuring out what clients want out of the financial planning relationship is sometimes contingent on getting clients to express what and why things are important to them. In short, because finances are deeply personal, good advice is built not just on a foundation of expertise and recommendations that accounts for the client’s capacity, but also on an emotional connection that allows the advisor to identify the client’s overall vision based on their values. By adopting a “coach approach” to financial planning, advisors focus on giving advice that clients will actually follow and that adapts to their changing financial circumstances and emotional priorities.

There are different coaching methods that advisors can use to better visualize and comprehend client goals, each that focuses on different aspects of how coaches can better connect with their coachees. This may range from client self-discovered solutions (International Coaching Federation Model) to an in-depth drill on who is sitting across from them to avoid giving the wrong advice or solving the right problems for the wrong reasons (the Who, How, What Coaching Model). Or it may focus on bridging the gap between what’s ‘Here and Now’ for the client and their desired outcome of ‘There and Then’ (Coach U Strategizing for Success Model). Each coaching method has its own emphasis, which advisors can choose to play to their strengths – or stretch themselves to learn new skills!

Once a client’s goals are clearly visualized, there still remains the issue of action, and at the same time, overcoming inaction. To this end, advisors can guide clients through areas that may be blocking their progress, such as by helping them tackle important tasks that have been difficult for them to complete. If a client feels reluctant or paralyzed by negative emotions, it may help to explore and identify options that clients may not have previously realized were available to them. Lastly, advisors can set up a systematic process with tools such as LifeCards and LifeMaps that can help clients lay out what their specific priorities and goals are—and give them something to be motivated about.

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors can consider a ‘coach approach’ as an effective way to bridge the gap between their technical knowledge and helping a client apply it to the relevant things that matter most to them. It can be leveraged to both onboard new clients and help existing ones move into action. Furthermore, when advisors use a coach approach, they place themselves at the intersection of a client’s life and money, which ultimately helps clients realize their life goals and achieve their desired quality of life!

Early in my career as a financial advisor, I was at an industry conference oriented toward younger planners, where I began voicing my early observations in working with clients. My conviction that successful navigation of personal finance seemed vastly more personal than financial received unanimous, if not anecdotal, agreement from other attendees through our commiserations.

This catalyzed my missional pursuit to better understand the personal side of personal finance – the intersection of money and life – by examining the qualitative personal drivers of our clients in our navigation of the quantitative technical aspects of their financial plans.

First, I studied with Rick Kahler and Ted Klontz in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where I learned about the unarticulated “money scripts” that drive our financial actions and inaction. Then, in the Pacific Northwest, I learned from Carol Anderson and Amy Mullen at Money Quotient how various tools and techniques could be woven into a financial advisory practice to help chart a path to a client’s “ideal future vision.”

Later, I learned from George Kinder and Louis Vollebregt at the Kinder Institute for Life Planning how to be (and how not to be) in pursuit of “lighting the torch” within our clients. Culminating with my receipt of the Kinder Institute’s Registered Life Planner designation was a convergence of an obsession with the field of behavioral economics and finance that seemed to scream that the notion that personal finance is more personal than finance doesn’t just resonate with us anecdotally; it’s also backed by scientific research.

Despite having more than enough to practice and preach from what I’ve learned through these and other life planning thought leaders, my curiosity took me most recently into the world of professional and executive coaching when I enrolled in a 70-hour personal, executive, and corporate coaching course taught by Master Certified Coach, Pamela Richarde, of Coach U. What might we have to learn, I thought, from those outside of our profession?

You can imagine my pleasant surprise, then, when, on the second day of our training, Ms. Richarde mentioned as an aside that the original founder of the now-international coaching movement, Thomas J. Leonard, was actually a financial advisor in search of a better way to understand, motivate, and move his clients to action! 🤯

Having just completed the requirements to be a graduate of Coach U’s Core Essentials program, I’d love to share with readers a ‘coach approach to financial planning’—why it’s important for us to explore as practitioners, what it could look like in action, and why and how advisors weave coaching into their wealth advisory practices.

Why A Coach Approach Is Better Than ‘Just’ Doing Financial Planning

“Hey, I’m a numbers guy,” my banker friend likes to say when we’re in the midst of company where he feels as though his status as statistician will lend credibility to his opinion. Indeed, many advisors may have gotten into the business of personal finance because they’re “good with numbers,” thinking they would charge a premium to transfer that numerical knowledge to those who are arithmetically challenged. In fact, a Kitces Research study showed that an “Interest In Personal Finance” was the #2 motivator for becoming a financial advisor after the desire to help/service others. However, they soon come to realize that the majority of what we do with clients doesn’t really require more than middle school math, and that the greater challenge in financial planning isn’t bringing new mathematical revelations to clients but helping them clarify and act on inklings they already have.

Personal Finance Is More Personal Than Finance

To be fair, there is a vast amount of information embodied in the field of financial planning, owing primarily to its expansive breadth of scope. A general comprehension of this sphere is certainly a prerequisite for those of us who are financial advisors. And knowledgeable financial advisors certainly can (and do!) bring valuable insight to bear when clients lack an understanding of financial planning principles. But just how valuable is advice that isn’t acted on?

And that’s where the problem lies. The problem is not so much in giving advice but in giving “advice that sticks,” as psychologist and executive coach Dr. Moira Somers would say. In one study, Russ Allen Prince found that half of the clients who’d paid for a formal financial plan implemented less than 20% of the recommendations given. Worse yet, at the other end of the spectrum, almost 20% of them implemented nothing at all.

And that’s where the problem lies. The problem is not so much in giving advice but in giving “advice that sticks,” as psychologist and executive coach Dr. Moira Somers would say. In one study, Russ Allen Prince found that half of the clients who’d paid for a formal financial plan implemented less than 20% of the recommendations given. Worse yet, at the other end of the spectrum, almost 20% of them implemented nothing at all.

But I’d bet that fellow fans of behavioral economics aren’t surprised to learn this. Students of Daniel Kahneman’s work know that most of our decisions as humans are driven by our faster and more emotionally-based ‘System 1’ processor that drives our decisions before we even have an opportunity to ‘think’, not our slower-thinking and reflective ‘System 2’ that takes the time to process through decisions logically. Fans of Jonathan Haidt’s research are aware that our System 1 processor, representative of our emotional impulses and analogous to a powerful elephant, wins in the decision-making process every time it is in conflict with its rational rider, our System 2 processor.

So should we really be surprised to learn that up to 80% of our rational recommendations aren’t implemented when 80% of their clients’ decisions are made without consideration for rationale? Is it possible that most advisors are simply speaking the wrong language to clients? That we need to learn to speak ‘elephant’?

The problem that most clients have isn’t knowing what to do, but doing what they know, as the saying goes. Yes, it might help to be a ‘numbers guy’, to borrow my banker friend’s phrase, in order to make sound recommendations. In order to help ensure your clients act on those recommendations, though, you’d better be a people person and a student of human behavior.

This is where financial planning proper seems to stop and where coaching picks up. Or does it?

Coaching Is Simply Financial Planning Done Right

While the CFP Board’s definition of financial planning may not be the only one, I think it’s fair to say that, when it comes to articulating what advisors do and how they do it, the voice of the CFP Board is the most recognized and influential.

Take a look at their newest definition of financial planning in the updated Code and Standards published in October 2019:

Financial Planning is a collaborative process that helps maximize a Client’s potential for meeting life goals through Financial Advice that integrates relevant elements of the Client’s personal and financial circumstances. [emphasis added]

Now please pause for 10 seconds, reread that, and consider the impact of the words “collaborative,” “life,” and “personal” in that definition.

Furthermore, when the CFP Board outlines the practice standards for the financial planning process, the very first step, “Understanding the Client’s Personal And Financial Circumstances,” delves deeply enough to mandate the collection of both “Qualitative and Quantitative Information,” even offering examples of the former, including values, attitudes, expectations, goals, and priorities.

The CFP Board goes even further in its fourth step, “Developing the Financial Planning Recommendation(s),” clarifying that information a CFP professional “must” consider when making recommendations includes “how the recommendation is designed to maximize the potential to meet the Client’s goals, the anticipated material effects of the recommendation on the Client’s financial and personal circumstances, and how the recommendation integrates relevant elements of the Client’s personal and financial circumstances.”

Wow! Did you catch that? Financial advisors aren’t just on the hook for giving recommendations as CFP practitioners, but for designing them in such a way that they are maximized. And, as noted before, the key to maximizing recommendations (i.e., getting clients to follow those recommendations) is to understand how to make recommendations speak to the clients’ System 1 brains – the faster, emotional, and more impulsive thinking mechanisms used to make decisions – which is exactly how a good dose of coaching comes in handy.

But the advisor’s job is still not done! As in its final, circular step of the financial planning process, the CFP Board reminds advisors that they need to perpetually “obtain current qualitative and quantitative information concerning the Client’s personal and financial circumstances.”

In other words, people change, and it’s part of the advisor’s job to know how their clients are changing and what impact that change might have on the work they do for their clients. Because while traditional financial planning has historically emphasized the technical requirements that would help clients optimize their insurance and investments as the primary focus of the plan (with the client’s lifetime goals being used to justify those product recommendations), the new reality of what ‘good’ financial planning looks like places more emphasis on what’s actually important to the client – in helping them reach their unique goals, and viewing insurance and portfolio assets as auxiliary resources to meet those goals.

And so for financial advisors, providing ‘good financial planning’ means that they need to be able to recognize not just how their solutions can fit into what’s important to the client, but also how to help them really take the action steps necessary to achieve their goals in a financially responsible manner that is in alignment with their priorities and values.

In all of this, the qualitative is inextricably intertwined with the quantitative nature of the financial plan. There’s no escaping it, and there’s no definition of financial planning that leaves room for opting out of that which many in the industry have denigrated as “the soft stuff” – where it’s not just what is recommended to the client, but how the recommendation is delivered that also matters.

The biggest challenge we tend to have with the CFP Board standards and process is that they tell us what we need to do without telling us how we should do it.

For example:

- How do you explore your client’s values, attitudes, expectations, goals, and priorities?

- How do you custom-design recommendations for clients so they’re delivered in a manner that increases the probability of their implementation?

I believe the answers are found in bringing the wisdom of professional coaching into the realm of financial planning. In fact, I’ll take it a step further:

Coaching, by whatever label you want to apply, is simply part of good financial planning. It’s financial planning done right.

Three Coaching Models: What Does A Coach Approach Look Like?

Let’s consider what a coach approach to financial planning could look like by examining three different, yet complementary, coaching models, beginning with the model developed by the International Coaching Federation (ICF), the primary credentialing body in the world of personal, professional, and executive coaching.

The International Coaching Federation (ICF) Model

The ICF coaching method includes a set of steps that position coaches as guides who facilitate the client through a discovery process, where the advisor doesn’t drive the recommendations but instead leads the client to their own self-generated solutions, to which advisors then hold them accountable for follow-through and implementation.

The central steps in this ICF coaching process are:

- Discover, clarify, and align what the client wants to achieve;

- Encourage client self-discovery;

- Elicit client-generated solutions and strategies; and

- Hold the client responsible and accountable.

The first and final steps in this model should look very familiar to financial advisors, as they’re reflective of processes that most advisors are already undertaking. Step 1 of the ICF coaching model – discovering, clarifying, and aligning with goals – are direct parallels to steps 1 through 3 in the CFP planning process – understanding circumstances, identifying goals, and analyzing the course of action. The final, ongoing step in the ICF coaching model is all about accountability, and aligns with the last standard in the CFP financial planning process that emphasizes monitoring and updating responsibilities.

Where advisors might likely be less familiar is with steps 2 and 3 in the ICF model, which can seem ambiguous in regard to the primary actor designated in these steps. Because the CFP process puts the burden to analyze and recommend primarily on the advisor, while the ICF method puts the client at the center.

This is where I believe many financial planners tend to miss the boat, and where the coaching world has the most to teach us. Perhaps the best way to make recommendations “designed to maximize the potential to meet the Client’s goals,” as the CFP Board instructs advisors to do, is perhaps to be less instructive!

In her eminently actionable volume, Advice That Sticks, Dr. Moira Somers implores that advisors “do not need to impress or educate clients as much as [we] need to understand and involve them,” further asserting that “[c]lient satisfaction, it turns out, is directly related to the amount of airtime that the client takes up in meetings.”

This goes beyond the truism that “we have two ears and one mouth and should use them proportionately.” Strategically, our clients will stick with the advice of their own creation more than our recommendations, however brilliant, so it is in providing the safe space for self-exploration where the advisor’s value can really be amplified, and not in the proposal of advisor-generated solutions, but the refinement of client-generated solutions where an advisor’s recommendations can be maximized.

But where exactly does that leave the financial advisor? When do we get to change into our financial superhero get-ups and save the day? Ideally, according to the ICF model, never. Advisors are not supposed to be the heroes of their client’s financial plans – the clients are their own heroes. If advisors want to increase the effectiveness of their plans, they would do well to position themselves as guides, not heroes.

The Who, What, How Coaching Model

Now let’s glance at one of the simplest coaching models that underscores where advisors’ individual planning processes are likely the weakest, which is in identifying the important aspects of who their client is beyond what may be in their portfolio. “Often in a coaching interaction, the coach is tempted by the two-step coaching model,” reads the Coach U Inc. Personal and Corporate Coach Training Handbook, which suggests that “…the coach will move to solving the presenting problem, skipping over the discovery of the true who in the scenario.”

You could easily replace the words ‘coaching’ and ‘coach’ with ‘advising’ and ‘advisor’ here, because even more than having a penchant for dollars and cents, I believe this is what has driven many advisors to be advisors – our affinity for problem solving. But if we skip the all-important step of really understanding who we’re problem solving for, we could find ourselves solving the wrong problems, or solving the right problems for the wrong reasons.

Thus, the client-centric model’s name of ‘Who, What, How’ emphasizes the key points of the coaching process: clearly identifying the unique client with the specific problem to be solved (‘Who’), understanding the problem that the client is facing (‘What’), and only then developing the most appropriate solution the client can use to solve their problem (‘How’).

For example, a client might declare that they want to have $5 million in retirement savings, $2 million of life insurance, or the means to quit their job and move to the Australian Outback. And the advisor may have done the initial ‘data gathering’ work to identify those client goals. In turn, the advisor could then analyze the client’s current situation, and develop a plan with recommendations for achieving any or all of those goals. But lost in the process is getting a genuine understanding of who the client is, and the deeper motivation they have behind reaching those goals. Why $5M in retirement savings, and not $4 or $6 million? Why $2M of life insurance? Why the Australian Outback, and not some other part of the US or the world? Without delving further into the “Who” to understand what has led the client to these stated goals, advisors could be missing the vital step that, when better explored, could have a dramatic impact on the plan.

In short, financial advisors may already be masters of the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ – but what about their ability to identify and work in alignment with the ‘who’?

Advisors may find it useful to ask themselves if they have a systematic process in place for exploring who their clients really are, and what their deepest-held values and motivations are. Where it’s not about identifying the client’s goals, but understanding why those goals are the goals in the first place (which can impact everything from whether those really are the ‘right’ goals, to whether the client will truly act in a motivated manner to implement action steps and achieve them). This is where coach-like thought leaders within the realm of financial planning have been incredibly helpful:

George Kinder’s 3 Questions is a legendary self-exploration tool that does an exceptional job of revealing who our clients really are;

George Kinder’s 3 Questions is a legendary self-exploration tool that does an exceptional job of revealing who our clients really are;- The author trio of Kahler, Klontz, and Klontz (the financial planning thought leaders, not a law firm!) have illuminated many advisors and many more clients through their work on “money scripts,” found especially in their books, the client-friendly The Financial Wisdom of Ebenezer Scrooge and the advisor/coach textbook Facilitating Financial Health;

- Money Quotient offers a host of tools that are designed to reveal the ‘Who’ within clients; and

- Susan Bradley’s work at the Sudden Money Institute is centered on the notion of figuring out who clients are before launching into what strategies will help them navigate major life events.

The Who, What, How Model can serve as an effective reminder of the key imperatives in an advisor’s work. It’s at least deserving of a sticky note attached to the advisor’s computer with the word “WHO” on it!

Coach U Strategizing For Success Coaching Model

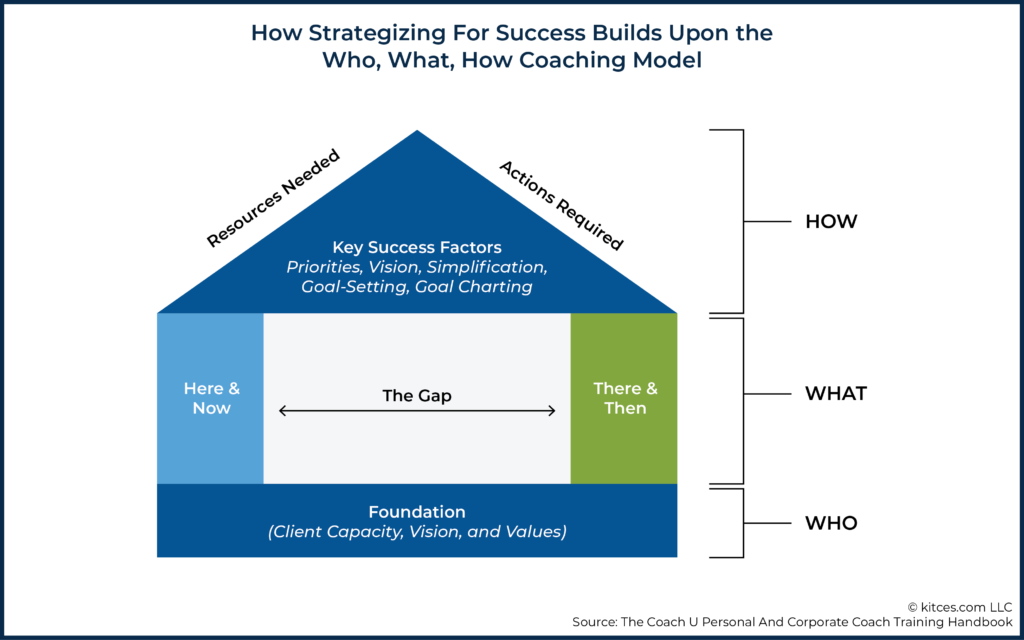

While the Who, What, How (WWH) model may be the simplest and most easily applied coaching model in our work with clients, the Coach U Strategizing For Success model builds on the WWH model and offers a powerful visual that represents a coaching method financial advisors can use with their clients.

When a client comes to their advisor for the first time, they bring with them their present situation – the ‘Here and Now’ – whatever that may be. ‘There and Then’ is the outcome the client would like to achieve – the 'What', if you will, of the framework for the Who, What, How model – and the 'Gap' is the distance in between the client’s current state and the desired outcome that they hope to bridge.

But before going the distance to reach ‘There and Then’, advisors first need to ensure a strong Foundation through an understanding of who the client really is – what their vision and values are, and what their capacity is to withstand the journey ahead.

These three factors – the Foundation, Here and Now, and There and Then – are all gleaned through a sound initial discovery (or rediscovery) process with the client that is likely not dissimilar from what many advisors likely already have in place (assuming their process is designed to illuminate the qualitative as well as the quantitative). From here, advisors can orchestrate the How required to bridge the gap between ‘Here and Now’ and ‘There and Then’ by identifying the Actions Required and Resources Needed.

The case is made that no one is better suited to do personal coaching than financial advisors—because they understand the resources needed and the actions required that are often not common knowledge, without which virtually any strategy for success is likely to result in failure.

The Key Success Factors prescribed by Coach U are the following:

- Clients’ priorities should be revealed in the discovery process of identifying who they are;

- This is the synthesis of a client’s priorities and their motivation behind (and beyond) them;

- It is more the job of advisors to offer simplified solutions that clients can understand and implement, more than it is on educating the client on the technical theory of their financial plan;

- Goal Setting. While goal setting may come naturally for advisors, having an actual process of setting goals with clients is important to ensure that Priorities and Vision have been accurately communicated and are reflected in the goals established;

- Goal Charting. Charting the progress of reaching goals should not be underestimated; most clients enjoy a great deal of satisfaction from reaching their outcome (and being acknowledged for their achievement!); furthermore, momentum from progress made can be recycled to catalyze the progress on other goals to be achieved.

It may be tempting to look at these models and surmise that coaching is simple, perhaps even simplistic, and verging on self-evident. But the best coaching tools often appear so; the simplicity of the models is intentional, as the keys to their effectiveness lie in the flexibility an advisor has to design a usable process that integrates the principles presented by the models, yet that can be adjusted as needed for each individual client.

You may be looking at these three models and thinking, “Eureka – this is what I’m already doing, so I’m good!” This is a temptation to be sure, but instead of finding self-satisfaction in your client experience’s areas of strength – its own form of ‘confirmation bias’ – I invite you instead to seek out the areas where it, and where you, can be stronger. And if you’re looking for where those areas of weakness might be, you’ll likely find them in the first and (especially) second points of the ICF model, the Who in the WWH model, and in the Foundation of the Strategizing for Success model.

Now, let’s look at three tools pulled directly from the world of coaching that might be especially applicable in the advisory realm.

Three Coaching Tools That Advisors Can Use

The ICF coaching model, the Who What How coaching model, and the Coach U Strategizing For Success model, are all frameworks for how coaching can be applied in an advisor-client relationship. But in practice, the intentional ‘simplicity’ of coaching models can also make it difficult to figure out the next steps to take to actually incorporate more of a coach approach into an advisor’s practice.

Fortunately, though, there are a number of practical coaching tools that advisors can draw upon directly to implement with clients and help them better achieve their (more clearly understood) goals.

Overcoming Incompletions

Incompletions are undone ‘to-dos’ and can have the opposite effect of the positive momentum built from the completion of a task. Willpower is an exhaustible resource, and incompletions are often a source of unnamed stress, as well as the conscious or unconscious barriers to setting forth on our next desired achievement adventure. Therefore, it is in uncovering these incompletions that we can catalog and deal with this potential barrier.

A good rule of thumb is to start the discussion as open-ended as possible, and grow more specific only when necessary. For example, I love George Kinder’s opening question:

So, why are we here?

Yes, it’s expansive, but there’s also an implicit client-centricity built into it, presuming that it is likely a life event or an observation of the client’s that is the meeting’s inspiration, even if it is occurring at the advisor’s invitation.

Contrast this with a phrase I commonly uttered at the onset of a client meeting prior to meeting Kinder, “How can we serve you?” Although clever, because it implies our team structure and our ‘servant’s heart’ mentality, it is ironically more about us than the client. And it is necessarily bound by what the client believes we do and don’t do.

The simplest way to address incompletions doesn’t require a questionnaire or a helpful visual; it involves asking a simple question:

What haven’t you done that you feel like you should do?

This could be a question asked in person, but I find that clients tend to answer this question slowly, as a lot of thought can be involved in each response. And because the pace tends to quicken once we add space for reflection, this could be a good exercise to give to a client in advance of a discovery meeting, asking them simply to jot down their answers.

Notably, the incompletions question could also be a question that might benefit from being discussed together, as the client may have limited experience working with a financial advisor and not realize the scope of what the advisor can help them do and that they should bring up in response to this question. Instead, they may find themselves compartmentalizing their answers into the box they perceive is within your numerical realm of expertise. Therefore, they’ll likely benefit from you qualifying that it could be anything that comes to mind.

Either way, though, by going through the exercise, they’ll have a clearer mind for whatever exploration you undertake next, and you’ll also find that most incompletions have financial implications associated with them anyway.

Of course, clients don’t know what they don’t know, so advisors may consider creating a checklist of some essential financial planning elements that allows clients to check off that which they have not yet completed. But it is a good idea to avoid the temptation of starting here. Generally speaking, it is most beneficial for the process of identifying incompletions to be client-inspired instead of advisor-led, as the responses will more likely reveal a more authentic assessment of the client’s “Here and Now” along with developing a more effective “How” in arriving at the desired “There and Then”. Accordingly, advisors may consider making their discovery process as open-ended as possible, both in general and specifically relating to the discussion of incompletions.

While it may be tempting to immediately turn every incompletion into a new financial planning recommendation, advisors should remember that clients can’t do everything at once. The advisor can offer valuable expertise to clients by guiding their inclinations with knowledge that will help them prioritize, and ultimately tackle, their various incompletions.

In fact, one of the best ways to help clients accomplish more is to ask less of them at any one time. For example, I wouldn’t recommend having more than three open action items expected of a client at any given time. (If you want to know why, check out Jim Benson’s “Introduction to Personal Kanban.” I’ll give you a nickel if you don’t begin to apply this in your own personal productivity system, too.)

A more expansive and proactive coaching tool used to help clients uncover incompletions is the Clean Sweep Program found in Coach U’s Essential Coaching Tools book. This 100-point exercise is designed to offer a comprehensive review of four primary areas of a client’s life – Physical Environment, Health and Emotional Balance, Money, and Relationships – delivering at its conclusion both categorical scores and a composite score.

Much of the content within the Coach U program falls outside of the blurred borders of “traditional financial planning,” but for those advisors who are charging boldly into a truly holistic approach, I can attest personally to the value of completing this exercise and the validity that it can have within the financial planning process.

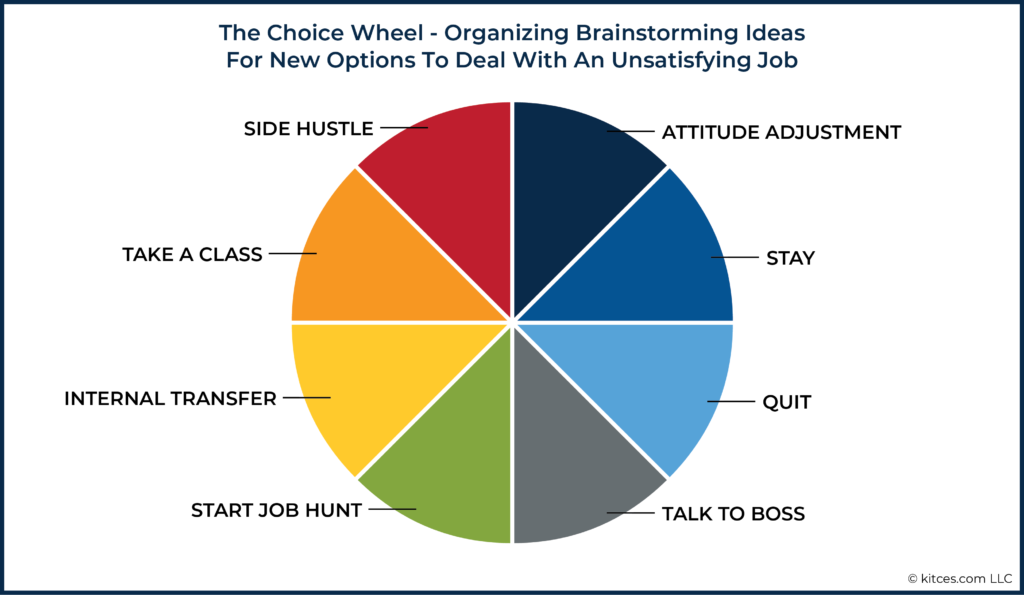

The Choice Wheel

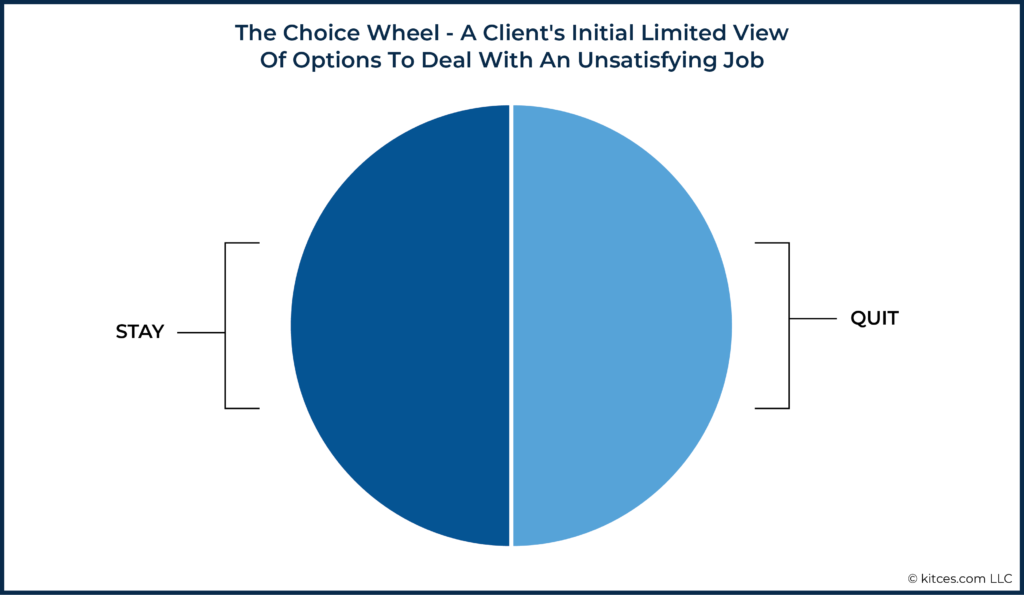

Transitioning from a broad exploratory tool to a more focused aid, the Choice Wheel is a simple, helpful tool to use with clients facing an apparent “I don’t have a choice!” scenario, or when they’ve backed themselves into an unattractive either/or dualistic dilemma, and is intended to open their minds to choices beyond their initial, limited purview.

Consider, for example, someone who is unhappy with their job. They may view their options as confined to either quitting their job (and eliminating their income, which they can’t afford to do) or hating their job (and “sucking it up” even though it’s making them feel miserable).

Instead, ask clients to try a brainstorming exercise designed to illuminate what other options might exist, no matter how silly they seem. Again, it’s a good idea to withhold the burning desire to fill this in for clients. Give them the gift of silence. Let them get on a roll, and they will.

For instance, simply asking the client “Can you think of any other options to pursue given your unsatisfying job, besides just ‘stay and be miserable’ or ‘quit when you can’t afford it’?” and then letting the client think and respond may elicit the following response:

When the client’s perception matches the reality that they are not simply limited to the two choices they originally thought were their only options, and that they have in fact several viable options available to choose from, the client a) is now relieved of the feeling of being stuck that can sap our decision-making energy, and b) may well have discovered several serviceable new options to add to their decision-making architecture!

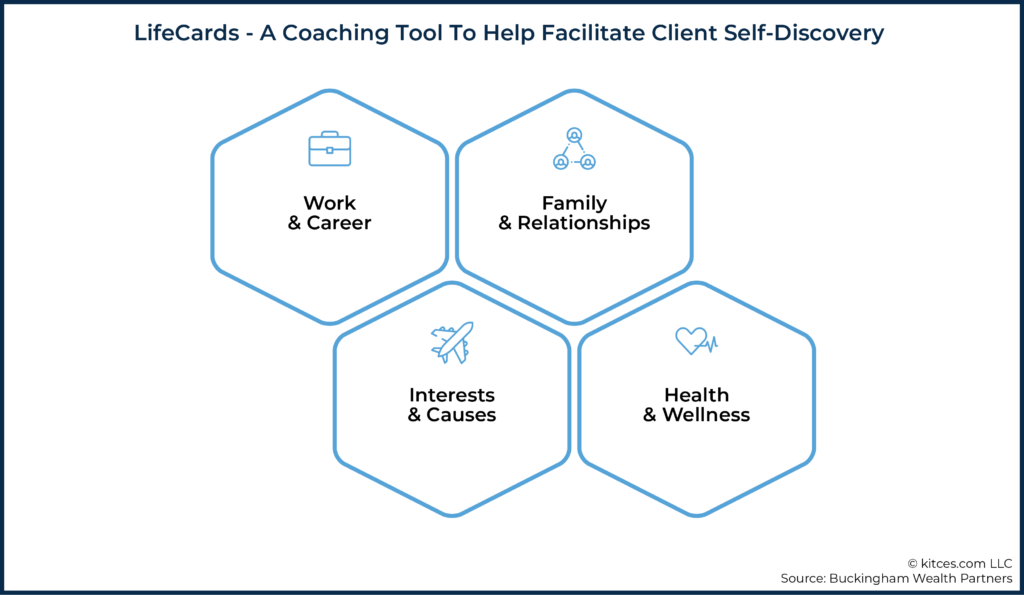

LifeDiscovery

Having now shared some ideas directly from the world of professional coaching that are ripe for advisors to modify and apply in their financial planning practices as they deem appropriate, I thought it would be helpful to illustrate an example of a coach approach methodology and two companion tools—LifeCards and a LifeMap—that we’ve created and embedded within the Design | Build | Protect client experience at my firm, Buckingham Strategic Wealth.

It’s called LifeDiscovery, a qualitative information-gathering method that is used during a meeting and designed to be an approachable way for both clients and advisors to better explore the ‘Who’ in pursuit of the most effective ‘What’ and ‘How’. Yes, as experienced advisors and as CFP practitioners, we’ve been told to uncover client values, but we’ve been offered very little regarding bringing that practice to life. This is the purpose of LifeDiscovery, and here is a recommended setup, a brief walkthrough of the process, and a look at the two key coaching tools that are built within.

Setting The Stage

Whether conducting a brand-new client discovery meeting or a rediscovery session with your oldest client, it’s vitally important for advisors to properly set their expectations that the entire (or vast majority of the) meeting will be dedicated to this process. In our LifeDiscovery process, the purpose that we share with our clients is designed to be simple, straightforward, and accessible:

We want to learn what’s most important to you in life to ensure that our collaborative financial plan is in alignment with those priorities.

For the skeptics who fear that they’ll be ranging into uncharted, woo-woo, warm-and-fuzzy waters by using a coach approach, how many prospects or clients do you think will hear this phrase and say, “No, I think that’s a horrible idea!”?

Indeed, coaching doesn’t have to appear weird and doesn’t require a lengthy disclaimer either. Nor is it necessary, or even helpful, to announce it with fanfare, lest it be presented or received as an unnatural part of the process.

The Process

The very nature of open-ended conversations with clients requires a great deal of flexibility in the navigation of any process and a willingness to go where the client leads, but we do offer four phases as a natural rhythm:

- Explore life areas;

- Identify vision and values;

- Articulate and prioritize goals; and

- Address and overcome concerns.

The bulk of the effort – and value! – comes from the exploration itself. The method is designed to facilitate an open-ended, yet guided, exercise in self-discovery for the client.

The Tools

Advisors can help to encourage the client’s self-discovery process through the utilization of LifeCards—tangible, physical, representations of each life area akin to a branded drink coaster (although there’s an underground movement underway that involves craft-made wooden LifeCards with a vintage leather band around them).

The exploration ensues in the form of four areas of life that are common to most: 1) Family & Relationships, 2) Work & Career, 3) Health & Wellness, and 4) Interests & Causes.

There’s nothing magical about the life areas or cards, and although we undertook great deliberation to arrive at the life areas listed, including subjecting them to the critique of Dr. Moira Somers, I can assure you they weren’t handed down on stone tablets from above! What they have in common is their commonality and their familiarity—and that they are all clearly more personal than financial.

And they have evolved over time. You may notice that each single life area actually represents a duality. In the past, they consisted of a single word, but in their most recent iterative phase, we realized that using word pairings broadened the canvas for the client to explore and helped ensure that they were as inclusive as possible.

For example, an overwhelming number of our clients are likely to mention “Family” as one of their priorities, cards or no. But what about the minority who are happily single, recently divorced or widowed, or for whom the whole notion of family brings up painful memories from their past? Similarly, “Career” may be a major driver for our Gen X and younger clients, but what about our retired clients? For them, some version of “Work” will likely prove a helpful exploration. “Health”, for many, represents the absence of sickness, but “Wellness” is a way of life for many. Not everyone is charitably inclined, but most have a cause or “Causes”; and as “Hobbies” may sound frivolous as a life area, “Interests” can carry more weight. You get the point. They’ll surely continue to evolve.

You’ll note that I didn’t number these life areas, because even such a listing implies an order of importance, while the optimal design is to allow the client to choose which life area to discuss first, second, and so on. The cards provide a helpful context, but we want to provide as many opportunities for autonomy throughout.

While we do utilize a virtual version of the slides within the context of virtual discovery meetings—a lot of those over the past year!—we’ve also found it helpful to conduct a virtual meeting after initially setting the stage for the client by sending them a tangible set of cards in advance. This allows them to have a tactile component to the discovery process that complements the visual and audio elements of the meeting, and that helps to retain the client-directed benefits of a meeting held in person.

And if your first impression of the LifeCards is reticence, because they feel hokey or unnecessary, let me assure you that was also my first impression. Then I learned more about the science of learning, that the utilization of various senses — audio, visual, and tactile — helps accelerate and deepen connection and extenuate retention. Then, most importantly, I used them, first with fellow advisors, and then with clients, and they worked. Yes, they work to differing degrees — more for some and less for others — but they work.

We aim to navigate this discovery conversation with as few, open-ended questions as possible and healthy doses of silence to nudge clients toward sharing their insights without our interruption.

Let’s take a look at the key elements of a LifeCard coaching session and how the conversations might go:

- Resetting the Stage – Remember, we’ve already set the stage prior to the meeting, so the client shouldn’t feel surprised, but it’s important to reset the stage and refresh the clients’ memories by reminding them of the exercise and answering any questions they may have:

“Jim and Sandy, as I mentioned, in order to ensure that our planning is supporting what’s most important to you in life, we begin with [or periodically revisit] this discussion to guide our work. We’ve found that a great way to learn what is most important to you is to frame our discussion through several areas of life that are common to most. One of those life areas is represented on each of these cards [handing the cards to the client]. Would you please arrange them on the table and choose one of the cards to begin our conversation?”

- Open-Ended Question - It normally requires little to no prompting, but if a question is needed, once they’ve selected a life area, we’ll ask,

“What’s important to you about [life area]?”

- Empathy (Through Strategic Silence) – You’ve heard this word that is now verging on overuse, but it’s another element, like the uncovering of values, that is talked about more than practiced. What does empathy look like? Head nods, posture, and facial expression mirroring. What does it sound like? Gutturals, like “Hmm,” “A-hah,” “Yes,” “Interesting,” and an exclamation when appropriate. But most of all, empathy is strategic silence. We demonstrate our care for our clients, and we give them the space to unpack their thoughts through silence.

- Open-Ended Follow-Up – Step 3, and silence, in particular, will most often elicit everything you need to know on a particular LifeCard, but if the client is challenged to open up, or you feel like there’s more, an open-ended follow-up question like the anticipatory,

“What else?” Or to be more conclusive, “Anything else?”

Either of these phrases should serve you well. Please note, however, that I’m not including the popular, “Tell me more,” as one such prompt because its design is to deepen into a single topic rather than our aim at this phase of exploration…breadth.

- Repeat and Reframe – Most clients will ‘get it’ pretty quickly and require limited nudging from their guides, but if you feel like they’ve come to the conclusion of their thoughts on a particular life area, you can always say,

“Thank you for sharing that. Which life area would you like to discuss next?”

Furthermore, as the manifestation of this exploration often flows directly into illuminating client stories, you may occasionally need to reframe the conversation if you feel like they’re diverting too far from the intended path or struggling to find their way. You can do so simply by returning to Step 1 in an abbreviated form.

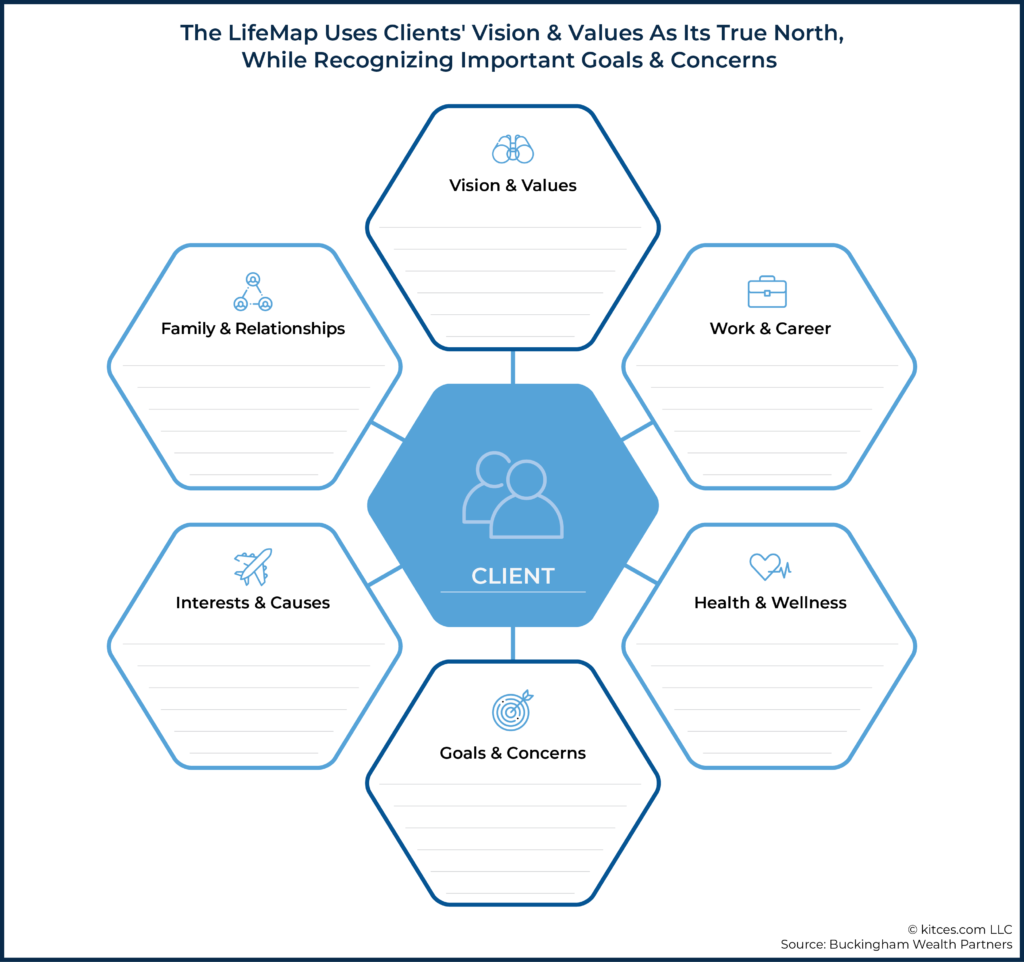

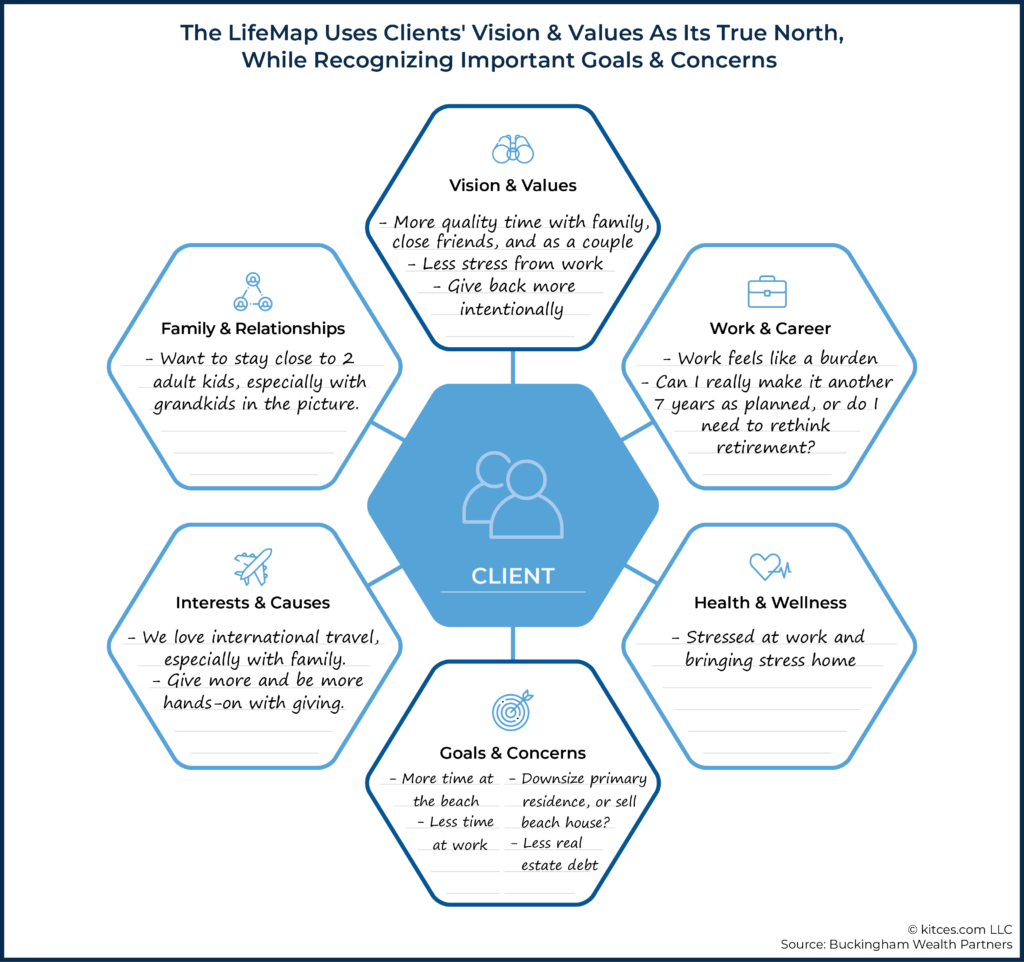

Then, what do we do with the insight gained from this LifeCard exploration? Enter the cards’ companion tool, the LifeMap.

The LifeMap is where we, as advisor guides, as coaches, note our primary observations from each of the four life areas for starters during our conversation with clients. This provides a great opportunity for active listening: “If I heard you correctly, this is what’s most important to you about ‘Interests and Causes’?” for example.

From there, we allow the insight gained in the exploration to bubble up to a statement, or short list of Vision & Values, most often (and ideally) articulated by the client in a form of their choosing. This becomes the true north on our planning compass, and it is from these core motivations that our purposefully limited number of goals (we only address three at one time) is drawn and prioritized.

While most discovery processes stop at the articulation of goals and move directly to implementation, we’ve added one additional step of addressing the client’s concerns to increase adherence to the plan. Instead of shying away from them, we actually invite the client to share their concerns about successfully reaching their goals, based on the fact that it is often these unspoken concerns that lead to incompletions—unimplemented recommendations.

Then, we allow the client to remain the hero of their plan by asking them what potential solutions might assuage each concern. And yes, you’ll have to bite your tongue so hard that it will hurt.

Let’s look at one of the more common examples: Suppose a client’s Vision & Values lead them to the life goal of “reducing work-related stress by converting to part-time work.” The accompanying financial goal, then, would be to “begin supplementing monthly income with a portfolio distribution.”

You ask the client, “What concerns do you have about that plan?” The client responds, “I don’t want portfolio withdrawals today to negatively impact my future lifestyle.” Of course you don’t.

So you probe further, “What’s a possible solution to lay that concern to rest?” They respond, “Well, I guess that’s why I’m working with you! Is that something we can calculate or model?” Indeed.

The articulable solution, then, is to “Collaborate with my advisor to model my future lifestyle to make sure I’ll be okay in retirement.” (Ok, that was an easy one.)

The visual LifeMap process is designed to provide enough space for advisor and client autonomy, but too little to drone on. This precludes losing the distilled essence that will help drive adherence to the great planning recommendations that flow from LifeDiscovery, a practice for which many advisors are already well prepared.

We also leave sufficient space in precisely how the LifeMap is built; some advisors use an enlarged whiteboard version of the map to develop collaboratively with the client, in real time, throughout their initial LifeDiscovery meeting.

Regardless of how the discussion pans out, we return regularly to the LifeMap in subsequent meetings with the client, as it becomes page one for every “report” or “statement.”

LifeDiscovery, through the utilization of the LifeCards and LifeMap tools, becomes the bridge into the important quantitative steps that need to be taken that are now supported by the client’s qualitative motivation, commitment, and excitement!

If you’re still with me, the chances are good that you’re one of the many advisors who’ve identified at least anecdotally with the scientific backing that personal finance is more personal than it is finance. But if you’re still a skeptic, I appreciate that, and I’ll offer a bottom-line conclusion that I hope will sway you to consider applying a coach approach to financial planning despite your hesitation.

In addition to generating higher levels of advisor satisfaction, I’ve observed that a coach approach is good for business – and may even become a business imperative. That’s because much of what would have differentiated your practice 10 or even 5 years ago no longer sets you apart. You’re an educated, credentialed, experienced advisor whose firm offers comprehensive financial planning as a fiduciary supported by evidence-based investment portfolios, right? Well, the 1-800 number at the unnamed behemoth firm purports to be all of the same, staffed with CFP professionals, who only charge $300 upfront and $30 per month!

Offering a coach approach to financial planning allows advisors to create a process that many larger firms simply can’t – and that will ultimately result in lasting relationships with an uncommon bond tempered by financial planning recommendations that are based on the personal goals and qualitative values of our clients. That’s what advisors who embrace a coach approach to financial planning can uniquely offer.

Indeed, every financial decision sends ripples through our lives, and most other choices we make in life also have financial implications in some form. Clients, therefore, need a guide who is skilled in navigating the intersection of life and money – financial life planning. While many advisors have the ‘financial’ and the ‘planning’ parts down, taking a coach approach can help us better navigate the vast middle realm that consists of understanding the values our clients have, along with their qualitative life goals and priorities.

Fantastic article, Tim! Thank you so much for sharing all of this detail and why coaching our clients is so important. It’s why I started my own firm, Make A Money Mindshift LLC, that emphasizes financial coaching before even getting into the financial planning piece. Coach first, plan second.™

Great article and good advice. I truly believe “coaching” your clients through the financial planning process is best and gives our clients true ownership of their financial future.

Magnificent article, Jim! I would tend to agree with you that personal finance is more personal than it is financial. Coaching is a tool for client empowerment and those aha moments are testaments of our commitment to stand aside and allow the real heroes to stand up. That's the rewarding piece.