Executive Summary

First introduced in the 1970s, index funds have grown in popularity over time thanks to their ability to provide broad-based diversification at (typically) very low costs, making their benefits available to investors of any level of wealth. And while mutual funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) have been the dominant way for investors to get index exposure, thanks to improved technological capabilities and reduced trading costs, direct indexing – buying the individual component stocks within an index – has emerged as an alternative tool with a range of potential use cases.

Historically, direct indexing was developed as a means to unlock the tax losses of individual stocks in an index – even if the index itself was up – and was primarily used only by the most affluent investors (who had the highest tax rates and benefitted the most from the available loss harvesting). However, direct indexing can be used not only to harvest tax losses but also to harvest capital gains (particularly for those taxpayers in the 10% and 12% tax brackets). In addition, direct indexing can provide tax benefits to investors who are charitably inclined by allowing them to donate the underlying shares within an index that have the largest gains, thereby helping them to maximize their tax savings.

For those whose primary goal is to benefit from a more personalized indexing strategy that still gains broad market exposure while specifically adjusting for personal preferences, using a personalized index can ensure the investor’s capital will support the exact industries or companies they wish to support (while also saving on the management fees otherwise charged by more packaged ESG/SRI mutual funds and ETFs).

The direct indexing framework also is relevant for advisors whose default strategy is to own “the market” (i.e., broad-based index funds), but who also want to overlay various rules that subsequently modify or tilt the allocations based on their own (or their clients’) investment preferences or outlook, such as over- (or under-)weighting certain sectors, factors, or segments of the market.

Finally, direct indexing can be used to help a client with a large, highly appreciated or concentrated investment position, or one whose human capital is tied up in one company or industry. For these clients, an advisor can build around the holdings committed to an existing company or industry by diversifying the remaining assets into an index, better positioning the client away from exposure to a potential downturn in their company’s (or its industry’s) performance.

The distinctions between the four types of direct indexing are important, as the various uses of direct indexing necessitate very different capabilities from the platforms themselves. Which in turn means that more than multiple different indexing providers can each have the potential for breakout success, by building the best-in-class solution for a particular direct indexing approach… while recognizing that what it takes to be most successful in one direct indexing category may be very different from what it takes in others.

Ultimately, the key point is that the value of direct indexing is no longer limited to tax benefits for high-net-worth clients. The developing uses for direct indexing – personalized indexes, rules-based advisor investment strategies, and customized completion portfolios – can benefit a wider range of clients. And while it remains to be seen whether direct indexing will start to displace mutual funds and ETFs in advisor-managed portfolios, its expanded uses, increased outside funding into direct indexing providers, and growing platform capabilities, suggest that direct indexing’s value to advisors is likely to expand in the future!

First introduced in the 1970s, index funds have grown in popularity over time thanks to their ability to provide broad-based diversification at (typically) very low costs, which makes their benefits available to investors at any level of assets.

While mutual funds were the dominant index fund vehicle for years, Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) have gained in popularity, particularly over the past decade, thanks to their often-lower costs than mutual funds, coupled with their tradability during market hours (whereas mutual fund transactions are only settled after the market close). Compared to mutual funds, ETFs also have a tax advantage, as the creation/redemption mechanics of the formation and liquidation of ETFs allows them to continuously rotate out older lower-basis shares for more recent higher-basis shares, minimizing or often fully eliminating any taxable capital gains distributions.

The caveat, though, is that while ETFs are internally effective at minimizing capital gains distributions (especially compared to mutual funds), they cannot necessarily generate pass-through losses on the underlying holdings in the ETF. For instance, if the S&P 500 in the aggregate is up for the year, but 150 of the individual stocks in the index are down, the ETF may not generate any capital gains distributions, but the investor would have no means of harvesting the 150 stocks that were at a loss.

Enter Direct Indexing. Historically, direct indexing was developed as a means to unlock the tax losses of individual stocks in an index – even if the index itself was up – and was primarily used by the most affluent investors (who had the highest tax rates and benefitted the most from the available loss harvesting).

However, developments in technology have opened up direct indexing to a much wider range of investors (as well as their advisors!) and to an expanding number of potential uses beyond their pure tax-loss-harvesting roots.

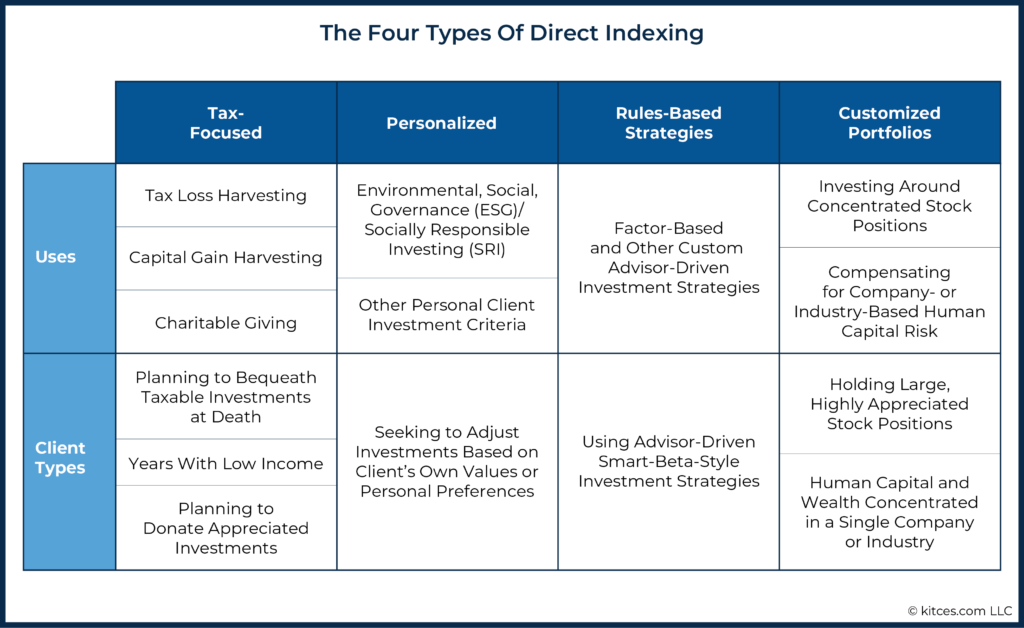

In today’s environment, there are effectively four different types of direct indexing – tax-focused, personalized investor preferences, rules-based, and customized portfolios – each requiring slightly different technology solutions. Which means advisors will need to be cognizant of the requirements of the direct indexing approach they select, to ensure they choose an appropriate direct indexing platform solution to meet the specific needs of their clients.

The Origins Of Direct Indexing

Direct indexing emerged in the 1990s, when the first firms that offered it – including Parametric and Aperio – pitched direct indexing as a tax-efficiency tool, where investors would skip buying an index mutual fund and instead own each of the individual component stocks of the index in their appropriate weightings, replicating the index itself but held in a manner that any stocks whose price declined could be tax loss harvested.

Tax loss harvesting allows investors to sell shares of investments whose value has declined since they were purchased, thereby ‘harvesting’ the losses; those losses can then be used to offset capital gains or other income in the same year the shares are sold. Although notably, tax loss harvesting is not a free lunch, as investors must wait more than 30 days before repurchasing a substantially identical investment. If they don’t, ‘wash sale’ rules would be triggered, which would not only disallow the deductible loss, but may also introduce potential tracking error to the extent that whatever the dollars are invested in during the 30-day waiting period will have returns that deviate from the originally-harvested stock.

Notwithstanding the tracking-error risks, though, for investors with sizable portfolios, tax loss harvesting benefits can be significant, potentially outweighing the costs of potential tracking error and the underlying transaction costs for buying and selling each individual stock (at a time where stock transactions still often cost $20/trade).

The need to purchase shares of each company within an index individually – incurring a $20+ trading charge for each – is what originally made direct indexing the purview of wealthier investors. As simply paying $20/trade for all 500 companies in the S&P 500 instantly created $10,000 of trading charges, and even more as the individual stocks were loss-harvested (incurring additional trading charges). Which meant it took a sizable account for the cost of the individual trades to be outweighed by the sheer size of the account and the available tax savings.

For instance, if an investor allocated $10,000,000 to the strategy and the average stock position was $20,000 each, a $20 ticket charge was ‘only’ a 0.1% transaction cost, while tax loss harvesting the stock could produce far more in tax savings. But if the investor only had $100,000, it certainly wasn’t feasible to allocate just $200 each across 500 stocks (where each $20 ticket charge would have amounted to a 10% transaction cost. In addition, since fractional share purchases were not available when direct indexing emerged, an investor needed a certain amount of assets just to purchase full shares of each of the component companies in the appropriate amount given their weight in the index.

Direct indexing largely remained the purview of high-net-worth individuals until 2013, when robo-advisor Wealthfront introduced its own direct indexing service. The Wealthfront 500, an index of 500 stocks meant to replicate the broad U.S. market Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF, was offered to clients with account minimums of $500,000 (and later $100,000) for a flat 0.25% advisory fee and no underlying transaction charges on each direct-indexed stock trade. Wealthfront argued that, in addition to the tax loss harvesting benefits of direct indexing, clients also benefited by not having to pay an expense fee for the underlying individual securities purchased (unlike mutual funds and ETFs, which have ongoing expense ratios).

This direct indexing exposure was particularly helpful during the long bull market of the 2010s, as while shares purchased of an index mutual fund or ETF were unlikely to decrease in value as the stock market rose (unless they were purchased soon before a brief downturn), some of the component companies of the index saw much more volatility during the period, creating opportunities to sell the shares of those that declined in value. And while the value of tax loss harvesting can depend on future changes to tax brackets (if, for instance, the repurchased asset is sold for a gain, the taxable gain will be larger because of the lower cost basis, potentially creating a larger tax burden if the investor’s tax rate rises between the year the loss was taken and when the repurchased asset is sold!), tax loss harvesting remains an attractive feature of direct indexing.

Notably, though, while Wealthfront’s ability to implement technology to deploy direct indexing at scale – and without cumbersome transaction costs – did expand how many investors could access direct indexing, the touted benefits were still largely focused on tax loss harvesting. But as advancements in advisor technology and reduced trading costs have continued, the potential uses for direct indexing have increased as well.

The Four Types Of Direct Indexing

Direct indexing is still best known for its tax advantages, but the decline and subsequent collapse of trading commissions, coupled with the rising ubiquity of fractional share trading, is resulting in an expansion of how direct indexing is used beyond its original tax-loss-harvesting focus.

As technology continues to improve, advisors can now leverage the direct indexing approach – replacing an index mutual fund or index ETF with the underlying stocks of the index – not only to widen the range of tax strategies (beyond ‘just’ tax loss harvesting itself), but also to create more personalized indexes that reflect client preferences, to create and implement their own rules-based investment strategies (e.g., factor-based investing) using individual stocks while avoiding the wrapper costs of mutual funds and ETFs, and even to design more customized portfolios that allow the advisor to construct a portfolio given unique client-specific constraints, such as a concentrated investment position or restrictions based on their employment.

Tax-Focused Direct Indexing

The opportunity for tax loss harvesting has been one of the primary selling points for direct indexing since its creation, but it is not the only tax advantage that direct indexing offers.

For instance, direct indexing can not only allow investors to more efficiently harvest tax losses, but also harvest capital gains as well. This strategy is especially appealing for those whose taxable income puts them in either the 10% or 12% ordinary income brackets (up to $41,775 for single filers and $83,500 for those who are married and filing jointly), as their long-term capital gains rate is 0%! And while those with employment income might find themselves outside of these brackets in most years, there might be years with lower income (perhaps after a job loss or starting a new business) where capital gains harvesting could be valuable. In addition, retirees who have not yet started Social Security benefits could find that they have significant room to harvest capital gains without exceeding the income limit (although these benefits should be weighed against the potential upside of partial Roth conversions in these years).

And again, just as direct indexing helps in tax loss harvesting by making it feasible to identify individual companies within an index whose share prices have fallen and to harvest their losses, direct indexing can serve a similar function for capital gains harvesting, selling the shares of a company within an index that has gained in value, without having to sell a share of the entire index (in mutual fund or ETF form).

And unlike tax loss harvesting, there is no wash sale rule when harvesting capital gains, so investors can simply repurchase shares of the company immediately after selling the old shares (thereby increasing their basis in the company’s shares, while paying 0% in capital gains taxes on the gains from the sale!), avoiding any exposure to tracking error from the index in the gains-harvesting transaction.

In addition to harvesting capital gains and losses, direct indexing can also provide tax benefits to investors who are charitably inclined. Because investments that have appreciated in value and have significant capital gains can make excellent candidates for charitable giving, as the investor can not only typically deduct the full value of the stock shares in the year of the donation (up to certain AGI limits), but doing so does not trigger capital gains taxes, effectively eliminating any potential capital gains tax that would have been owed if the shares had been sold.

Accordingly, because direct indexing allows an investor to selectively donate the underlying shares within an index that have the largest gains (instead of donating shares of an index mutual fund or ETF, whose gains will naturally be lower than just its highest-gaining components), it helps them maximize the size of the tax savings. And just as with capital gains harvesting, there is no wash sale rule for donating appreciated stock, so replacement shares can be immediately repurchased (avoiding any tracking error), which then receive a new cost basis at the current price (reducing future capital gains exposure as well). In addition, investors with a donor-advised fund may find direct indexing to be particularly useful, as highly appreciated shares can be moved into the fund at any time for later distribution to a charity, rather than having to select a charity each time candidate investments are identified.

Another related strategy for highly appreciated investments that direct indexing can facilitate is the decision to hold certain stocks “until death” so that they can receive a step-up in basis. As holding an index at the individual stock level makes it both feasible to trade individual lots for rebalancing purposes (cherry-picking the higher-basis shares and holding onto the lower-basis shares for a future bequest), and/or to adjust the rest of the portfolio around highly appreciated positions to extend their holding period further.

Altogether, direct indexing can offer tax benefits to a wide range of investors, including those with high incomes (who are in higher capital gains tax brackets and who would benefit the most from tax loss harvesting), those with low incomes (who are eligible to harvest gains at a 0% capital gains rate), and those who are charitably inclined (who have additional choices when investing in the individual shares of companies in an index rather than in an index fund).

Personalized (Direct) Indexing

Index funds offer investors exposure to the diverse range of companies that make up the index, gaining the opportunity to participate in the growth of ‘the market’ in the aggregate without needing to necessarily focus on the business or other merits of the specific companies within the index (a time-saving selling point for index investing).

At the same time, though, some investors that like the convenience of investing in an index might have concerns about certain industries or the activities of particular companies that make up the index. In these instances, direct indexing can be a useful tool for investors who are looking to over- or under-weight certain stocks on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) grounds, or to exclude certain companies in industries altogether under a Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) framework.

For example, investors concerned about the high environmental impact of fossil fuels by some companies will have at least some exposure to those companies (depending on their weight in the index) when investing in a broad index fund (such as one tracking the S&P 500). To avoid this, investors can instead choose to allocate to ESG/SRI mutual funds and ETFs that may have a stated mandate to only invest in clean energy, but will be subject to whatever ESG/SRI criteria the fund manager chooses (and their subsequent ability to execute it).

By contrast, within a direct indexing framework, the investor may choose to overweight their investments not just towards clean energy companies, but also to support wind-based renewables in particular, while entirely avoiding allocations to any petroleum-based energy companies, ensuring their allocations align to their exact preferences.

Of course, one potential cost of this approach (compared to a traditional approach of tracking the index exactly) is that by removing companies from the index or otherwise changing the weightings, the investor’s direct indexing returns are likely to differ from those of the underlying index itself (although this drift could be positive or negative).

Still, though, for those whose goal in the first place is a more ‘personalized’ index – gaining broad market exposure, but specifically adjusted for their personal preferences – investors using personalized indexes can ensure their capital will support the exact industries or companies they wish to support. While at the same time also benefitting from the ‘traditional’ tax advantages of direct indexing (e.g., capital loss and capital gains harvesting) to help offset the platform fees and minimize tracking error (while also saving on the management fees otherwise charged by more packaged ESG/SRI mutual funds and ETFs).

All of which, again, is far more feasible in an environment where transaction costs and fractional shares make it possible for a far wider range of investors than just those with the highest levels of wealth… at least, as long as they have the technology to implement their personalized preferences into their (direct-indexing-constructed) portfolios.

Rules-Based Direct Indexing

Many financial advisors prefer to invest client assets in mutual funds and ETFs due to the ease of implementation and the ‘instant’ diversification that comes from buying a fund, compared to constructing portfolios out of individual stocks. Of course, this convenience comes at a cost, in the form of fees charged by the funds (compared to equities, which are now typically free to trade and have no ongoing costs once purchased), along with a loss of flexibility in being allocated in whatever manner the mutual fund or ETF manager has constructed the fund. Which advisors have managed in recent years by utilizing increasingly finely sliced ETFs that take on more and more targeted allocations, allowing advisors to decide exactly which parts of the market they do and don’t want exposure to.

However, direct indexing platforms create the potential for advisors to implement their own investment strategies at the stock level, rather than relying on packaged funds and ETFs. For instance, an advisor that wanted to overweight technology and underweight industrials wouldn’t need to overweight one sector ETF and underweight the other… instead, they could simply apply a rule within their direct indexing allocator to overweight stocks tagged in the technology sector and underweight stocks tagged in industrials. Similarly, an investor who wanted to implement a DFA-style overweight to value and small-cap could simply use a rules-based system that automatically increases the weightings to such stocks when otherwise buying ‘the index’ and all of its component stocks.

Notably, this is largely a moot point to investment managers who are individual stock-pickers – and who already do individual stock analysis to buy/sell individual companies. Instead, the direct indexing framework becomes relevant for advisors whose default was to own ‘the market’ (i.e., broad-based index funds), but who also want to apply various rules overlays that subsequently modify or tilt the allocations based on their own investment preferences or outlook, such as over- (or under-)weighting certain sectors, certain factors, certain segments of the market, etc.

In essence, direct indexing provides a platform for advisors to create their own “Smart Beta”-style investment allocations, which is notable; as while direct-indexing platforms may be more expensive than traditional ultra-low-cost index funds (that are sometimes just a single-digit-basis-point expense ratio), they may actually end out being cheaper than Smart Beta ETFs (which, by one study, had an average expense ratio as high as 0.35%, even for large-cap Smart Beta). While also providing a framework for advisors to create their own Smart-Beta-style rules for allocating the portfolio.

The key distinction, though, relative to the other types of Direct Indexing, is that while Personalized Indexing is about crafting a portfolio that expresses the client’s preferences, Rules-Based Direct Indexing platforms are primarily about giving advisors a framework to trade and implement their own investment views and preferences on behalf of their clients (but using individual stocks as the building blocks instead of mutual funds or ETFs).

Customized Direct Indexing

Diversification is widely recognized as an important feature of portfolio construction. Yet while most client portfolios can be built from the ground up to entail the full breadth of their desired diversification, some clients will have special circumstances that necessitate more customized individual-specific adjustments from a ‘standard’ portfolio given their financial and other circumstances.

For example, some clients might have a large, highly appreciated position in a certain stock that they’ve held for an extended period of time (perhaps acquired via a gift, employee compensation, or simply an individual stock investment gone especially well), and don’t want to sell to diversify now. Perhaps because they simply don’t want to face the tax consequences, or alternatively perhaps because there is a goal to hold the stock as a future bequest for heirs (where it can receive a step-up in basis at death to eliminate the capital gains altogether).

Yet in the meantime, simply ignoring the stock and otherwise building a diversified portfolio with the rest of the client’s assets doesn’t alleviate the overweighting to a concentrated position, and in fact, may further amplify it because a broad-based index may be likely to hold additional shares of the same stock.

However, the alternative of using a direct indexing framework allows the advisor to actually use the existing stock itself as a substitute for that equivalent position in the index (e.g., keeping the client’s existing Microsoft holding and then buying the other 499 stocks in the S&P 500 around it), or even as a substitute for the entire sector (e.g., holding a large Microsoft position in lieu of the whole Information Technology sector and then buying the other 425 stocks in the S&P 500).

In other words, the client can potentially benefit from having their remaining assets invested so that their overall portfolio is not as overweight in the concentrated position (which would negatively impact portfolio performance if the concentrated position declined significantly), by building a ‘completion’ portfolio around the existing holding at the individual stock level.

Example 1: Maria’s client Bill has a $1 million portfolio, including $250,000 worth of Microsoft stock, which he bought in 1990. Given that Microsoft and other similar technology companies make up a significant part of the S&P 500, Maria does not want to invest Bill’s remaining assets into a broad large-cap index fund.

Instead, Maria uses direct indexing to take the S&P 500 and remove Microsoft and similar technology companies, allocating the remaining $750,000 across the other 425 stocks in the index.

As a result, Bill’s overall portfolio reflects the broader market as closely as possible… without doubling up on Microsoft or other technology stocks in the index and without being required to sell the Microsoft stock to otherwise diversify.

In cases such as these, the use of direct indexing is not about client preferences, but about ensuring client portfolios (and financial situations overall) are diversified and less subject to concentration risk, leveraging the fact that direct indexing builds portfolios at the individual stock level but with a chassis that still arcs towards more broad-based diversified index investing. Which can provide an appealing lower-cost alternative to other strategies for diversifying concentrated positions (e.g., exchange funds, options strategies) that can come with significant fees and/or lockup periods.

Another potential use of direct indexing is for clients whose human capital is tied up in one company or industry and who want to be certain that their financial assets don’t further concentrate their wealth dependency on the same company or sector.

For example, an executive at a public company might receive most of their compensation in the form of stock options, exposing them to significant financial risk if poor company performance not only led to them losing their job, but also seeing the value of their options decline as well (as many employees of Enron experienced in the early 2000s).

Similar to working around a similar stock position, an advisor could use direct indexing to diversify the client’s remaining assets into an index that is built around the existing company or industry, better diversifying the client away from the exposure to a downturn in their company’s (or its industry’s) performance.

Example 2: Brian’s client, Janelle, is an executive at a major oil company. She has a $3 million portfolio, which includes $1 million in shares of her company’s stock. Janelle is worried that a sharp decline in oil prices could impact her job as well as the value of her portfolio.

Brian uses direct indexing to adjust a broader market index to not only remove Janelle’s company, but also other companies with significant exposure to oil prices, building a completion portfolio of the remaining stocks in the S&P 500 to reduce both the company risk and industry risk of Janelle’s portfolio.

Notably, the key distinction of direct indexing in the context of this type of portfolio customization is that it’s not necessarily about expressing the client’s investment preferences for personalization, or the advisor’s investment outlook, but instead, a more granular client-level customization based on existing portfolio constraints around which direct indexing can facilitate a ‘completion’ portfolio of the rest of the holdings it takes to diversify the client (to the extent possible).

Implementing Direct Indexing Strategies

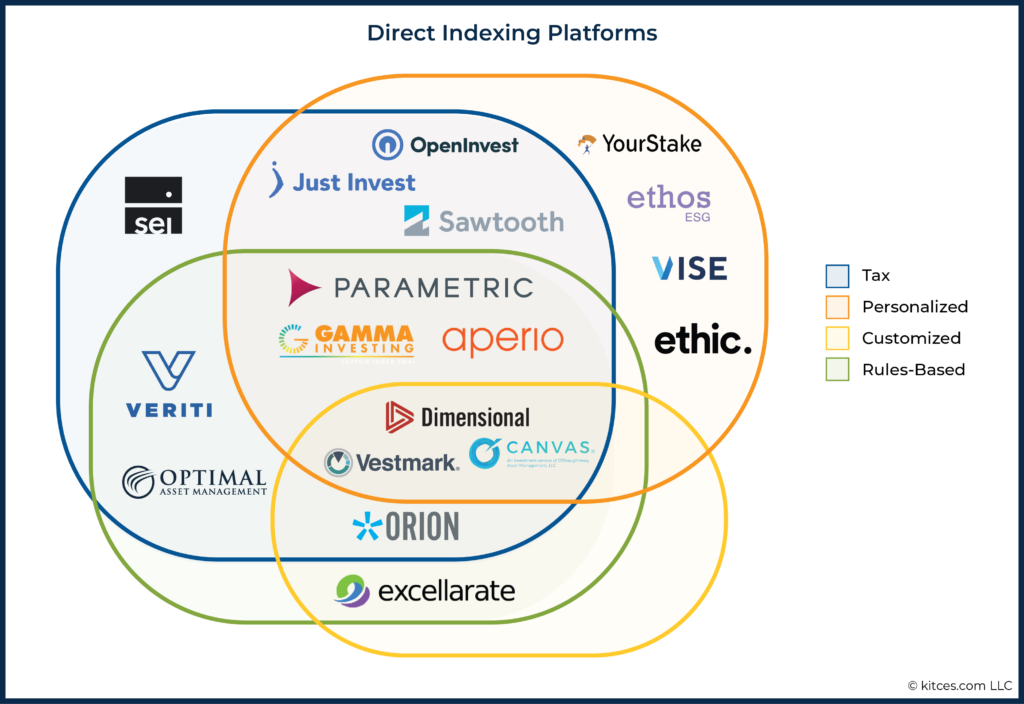

The number of direct indexing platforms has increased significantly as their potential audience and use cases have expanded beyond tax savings (for high-net-worth individuals), from more personalized indexing, to building customized completion portfolios around existing client constraints, to using direct indexing as a trading platform to implement an advisor’s own Smart-Beta-style rules-based investing strategies.

The distinctions between the four types of direct indexing are important as the various uses of direct indexing necessitate very different capabilities from the platforms themselves. Which in turn means that more than multiple different indexing providers can each have the potential for breakout success, by building the best-in-class solution for a particular direct indexing approach… while recognizing that what it takes to be most successful in one direct indexing category may be very different from what it takes in others!

Tax-Focused Direct Indexing Platforms

For tax-focused direct indexing, the best platforms will be the ones that do the best job of tracking the gains and losses of all the individual positions in the portfolio, by stock and by lot, and then make it easiest to identify which shares should be sold for various tax transactions – whether it’s to harvest the losses, or the gains, or extract positions for gifting or bequests.

For tax loss harvesting, this includes identifying the companies within an index that have gone down in value (to get the greatest tax benefit from the sale), identifying replacement securities to purchase (to reduce index tracking error), and ensuring that the transaction does not violate wash sales rules. For advisors interested in capital gains harvesting for clients, platforms should be able to not only easily identify potential candidates to be sold, but also allow advisors to track gains harvested throughout the year to ensure the client remains in the 0% capital gains bracket.

Advisors using direct indexing to maximize charitable deductions would benefit from platforms that identify the best candidates in terms of appreciation, but also eligibility (i.e., only donating stock held for at least one year so that both the basis and appreciation can be deducted). Recognizing that across a diverse client base, advisors may need to use all of these strategies, and determining which ones to implement will vary by client (e.g., a high-income client may need to focus more on tax loss harvesting, an affluent client with a low-income year may need to focus on tax gains harvesting, and a high-net-worth, charitably-inclined client may need to focus on charitable giving opportunities to their Donor Advised Fund). Platforms that integrate with advisor tax-planning software would differentiate themselves from other alternatives as well.

Personalized (Direct) Indexing Platforms

Compared to using direct indexing for tax purposes, creating personalized indexes for clients would benefit from substantively different platform features.

Given that the personalized index will be created with significant client input (regarding their preferences for which types of companies should be included, excluded, or under- or over-weighted within the index), platforms serving this use case would benefit from having a client interface for portfolio construction that is user-friendly for both advisors and clients. Which would serve to make it easier for clients to input their preferences to set their own allocations, understand what companies are being added (as while tax-focused direct indexing clients are seeking exposure to the broad index, clients with personalized indexes will tend to care much more about what companies are included!), and then helping to communicate to clients their results in the context of their stated preferences and goals for their personalized index (since clients expressing their personal preferences usually are not trying to produce superior investment results relative to a benchmark index, but instead want to receive affirmation that their capital was allocated in a way that supported their values and preferences).

In addition, to the extent that personalized indexing is all about tailoring a portfolio to the client's unique preferences - in particular, with respect to areas like values-based and ESG investing - the depth and breadth of the provider's data sources to provide more unique criteria on which companies can be screened to develop personalized allocations becomes increasingly important as well.

Rules-Based Direct Indexing Platforms

By contrast, advisors using direct indexing to implement their own rules-based investment strategies by leveraging direct indexes for their own form of Smart Beta would need platforms that have robust trading capabilities to systematically identify, implement, and monitor the execution of their rules-based trades.

For instance, creating a factor-based or similar direct index would require regular trading of the individual stocks within the custom index throughout client accounts, necessitating solid trade execution and rebalancing capabilities to ensure clients remain ‘on-model’. Performance tracking would also be an important feature, as the advisor’s proprietary rules-based indexing strategy will need to prove its worth by outperforming a benchmark index (net of fees).

Customized Direct Indexing Platforms

For advisors implementing customized completion portfolios for clients with concentrated human capital or legacy positions, having a platform with an exceptions-based framework that can be implemented in a scalable way would be most important. Working with clients with a range of needs (from those with a single concentrated position to invest around, to others that might need to avoid entire sectors), advisors in this group would benefit from a platform that offers efficient customization, tools to easily analyze and produce a completion portfolio that can show how much of the stock or sector risk has been reduced, and the ability to handle a wide range of clients who each have different unique customization circumstances.

Selecting A Direct Indexing Platform To Address Advisor Needs

While the original direct indexing platforms focused on tax benefits, the emerging use cases for direct indexing into personalization, customization, and as an advisor trading platform have led to expanded functionality not only among legacy providers but also among new entrants targeting one or more of the specific use cases for direct indexing outside of tax benefits.

The expansion of direct indexing from primarily tax strategy to uses in developing personalized indexes, rules-based advisor strategies, and customized completion portfolios, is a relatively nascent development, but the space has attracted significant outside funding from many of the largest asset managers, whose market share of traditional mutual funds and ETFs could otherwise be eroded by the growth of direct indexing solutions.

This surge in funding suggests that direct indexing is here to stay, but advisor and investor preferences are likely to drive the direction of future offerings across the four categories, and the success of specific platforms (to the extent they can fulfill the greatest needs within their respective categories).

For now, many of the direct indexing platforms market themselves as providing a range of direct indexing solutions, from tax loss harvesting to personalized indexes to customized completion portfolios, though some appear to be focusing on a specific use case (e.g., Ethic and YourStake for ESG/SRI investing). At this stage, it is unclear which of the direct indexing use cases will become the most popular, perhaps leading to a reluctance among platforms to focus on a single direct indexing niche.

At the same time, given that advisors will be looking for different platform capabilities depending on their needs (e.g., client portal for personalized portfolios or advanced trading capabilities for custom investment strategies), a platform that pursues a ‘niche’ by offering advanced tools for one of the major use cases could be in an advantageous position, especially if that use becomes increasingly popular.

Ultimately, the key point is that the value of direct indexing is no longer limited to tax benefits for high-net-worth clients. The developing uses for direct indexing – personalized indexes, rules-based advisor investment strategies, and customized completion portfolios – can benefit a wider range of clients and are not necessarily tax-focused (although these clients can still potentially benefit from the tax loss and capital gains harvesting benefits that direct indexing can provide).

As advisors look to implement direct indexing for their clients, they are likely to seek out the platforms that provide the most advanced tools for their specific use cases. So while it remains to be seen whether direct indexing will start to displace mutual funds and ETFs in advisor-managed portfolios, its expanded uses, increased outside funding into direct indexing providers, and growing platform capabilities suggest that its value to advisors is likely to expand in the future!

Great post. Shouldn’t the two graphics be links?

Kay

Hi Kay, thanks for reading and for flagging the graphics. They have been fixed!

Thanks for the thoughtful coverage. Well done! But I am confused by one statement regarding capital gain harvesting:

Is this assuming the shares are in a tax-sheltered account? Or that they’re being offset by comparable capital losses in a taxable account? Otherwise, how would selling the appreciated shares result in 0% capital gains taxes? What am I missing?

This statement in the article was made for individuals who fall in the 10-12% ordinary income tax bracket, which would equate to 0% long term capital gains tax rate. This is the demographic that will benefit from capital gain harvesting.

C8-Technologies are a small European firm (operating globally) setup in 2017 that sits in the middle of your Venn, next to Canvas, Dimension and Vestmark. We have the technology to address all 4 groups of investors.

I add that ETFs lack transparency on composition, there have been documented cases of ETFs purporting to be Carbon-ETF compliant only for it to be revealed that underlying portfolios contained fossil fuel producers, it is no surprise as said producers are big parts of the tracked index. This would suggest that their index-tracking technology is poor. Again on ETF providers, as holders of massive stock portfolios, they very easily influence company boards through voting rights a benefit that the investor never gets to enjoy. Further, as holders of large amounts of stock, ETF providers generate income through stock lending, an income stream that is generally not passed to the investor. The space is rife with conflict of interests and ready for disintermediation.

Much more can be said, pls reach out.

Ebrahim,

I am not necessarily familiar with the European direct indexing space and C8 seems like an interesting proposition. We are currently preparing a market research piece looking at: (i) the major participants in direct indexing globally; (ii) recent transactions and consolidation in the sector. Would you be interested in providing your point of view?

Let me know if interested and happy to reach out to you over Linkedin.

Thanks,

Interested reader!

This article was very well done – thank you. I have a general question on the use of tax-loss harvesting and direct indexing. Is there any research on the performance of this strategy vs. buy and hold or rebalancing? Clients love the idea of taking the loss and the short-term low tax profile, but longer-term, you are selling stocks when they are down. Is there any research that shows the harm of letting winners run too long or locking in losers’ losses? The ability to buy “similar” security is limited with individual positions. I love this approach for those with equity comp or ESG concerns, but I am concerned about the long-term performance of selling an investment just for the loss. Any thoughts? Thanks! Mark

Hi Mark, thanks for reading and for the comment. While it does not address direct indexing specifically, here’s a previous NEV article that goes into the weeds into the potential benefits of tax-loss harvesting: https://www.kitces.com/blog/evaluating-the-tax-deferral-and-tax-bracket-arbitrage-benefits-of-tax-loss-harvesting/. As you suspect, TLH is not necessarily a risk-free proposition, as the actual benefits of TLH depend on a range of factors, including any tracking error as well as the client’s current and future tax rates.