Executive Summary

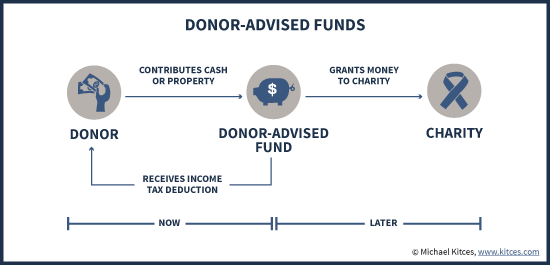

The primary benefit of a donor-advised fund (DAF) is that it allows someone to donate assets for charity today – and receive a tax deduction now – even though the actual funds may not be granted to the final charity until some point in the future. In other words, the donor-advised fund essentially functions as a conduit, where the donor receives a tax deduction when the money goes into the DAF, but has discretion about when the assets will finally leave the DAF and actually go to the charity… and in the meantime, assets inside a donor-advised fund grow tax-free.

Given the potential of a donor-advised fund to separate the timing of the contribution and tax deduction, from the final donation to the charity itself, the most common strategy for using a donor-advised fund is to “front load” charitable contributions in a high income year – when the tax-deduction threshold for charitable contributions will be higher – and then use the DAF to make subsequent distributions to the charities themselves in the future. By using the strategy, the donor can maximize the value of the tax deduction in a high-income year, but retain the flexibility to decide in the future to which charities the funds will actually go.

Notably, though, the donor-advised fund as a vehicle provides a mechanism for other charitable giving tactics as well. For instance, the donor-advised fund can facilitate giving anonymously, or creating an “In Memoriam” fund. The DAF can also help facilitate donating appreciated securities to a smaller charity that doesn’t have the means of handling the donation directly. And for some families, the donor-advised fund can function as a less expensive alternative to a private (non-operating) foundation, providing a means for the whole family to engage in the process of charitable giving, while allowing the tax-free growth of a family’s charitable legacy.

What Is A Donor-Advised Fund (DAF) And How Does It Work?

The basic concept of a “Donor-Advised Fund” is that it’s a form of tax-preferenced investment account, specifically ear-marked for charitable giving. Typically, a donor-advised fund (or “DAF” for short) is managed by a non-profit entity, which might be a charitable organization under the umbrella of a financial services firm, or a local community foundation.

Because any assets deposited into the account are required to ultimately flow through to a charity, the donor is eligible for a charitable deduction for income tax purposes at the time of contribution. The deduction amount is the fair market value of the asset contributed (for illiquid investments worth more than $5,000, an independent appraisal is required to determine the appropriate value for deduction purposes). The contribution to a donor-advised fund is treated as a gift to a 501(c)(3) public charity, which means the charitable deduction is limited to 50% of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) for cash gifts and 30% of AGI when donating appreciated securities (with the usual 5-year carryforward for unused amounts above the AGI thresholds).

As a charitable entity, once assets have been contributed into a donor-advised fund, they grow tax-free within the fund. Investment choices may be limited to the offerings made available by the sponsoring entity of the donor-advised fund, which may be as flexible as a brokerage account in some cases, and limited to a narrow list of pooled investment vehicles in others. For donor-advised funds held under financial services firms, it is often possible for the financial advisor to be hired/paid to manage the assets (though this is usually subject to non-trivial asset minimums).

Ultimately, assets in a donor-advised fund are meant to be granted to a charity. While a donor-advised fund is not required to distribute any donations, when it does do so, the donor-advised fund must make its grants to another public charity (that is in good standing with the IRS). As a result, donor-advised funds cannot make gifts out to split-interest trusts (like a charitable remainder trust or a charitable lead trust), nor can a donor-advised fund make contributions to a private non-operating foundation (although a private operating foundation is permissible), and gifts cannot be made directly to individuals either. Notably, grants to a charity must be solely for the benefit of the charity, and the donor cannot receive any goods or services in exchange; as a result, grants from a donor-advised fund to purchase tickets for a charitable event or a table at a charitable dinner are generally not permitted.

Notably, a donor-advised fund is not technically required to follow the donor’s guidance about how to invest the funds, nor about where grants will be made, although from a practical perspective a donor-advised fund that did not follow the guidance of its donors would quickly see its new contributions fall to $0. Accordingly, virtually all well-established donor-advised funds have a long history of follow the donor’s guidance about how to invest the funds (within the limits of what the platform offers in the first place) and likewise to follow the donor’s guidance about where to donate (after verifying the receiving organization is otherwise a permissible and bona fide charity to receive the funds, and that the grant will not violate the DAF limitation that the donor cannot receive anything in exchange for the contribution).

One unique aspect about donor-advised funds in particular is that they can be used to facilitate anonymous gifting, as the ultimate distribution comes from the charitable organization sponsoring the DAF, which does not have to disclose the details regarding the source. Alternatively, donors can choose to request that grants made out to the charity be acknowledged based on the particular donor-advised fund source (which might be based on the name of the donor, or even “In Memoriam” for someone who has passed away).

What Are The Requirements To Establish A Donor-Advised Fund?

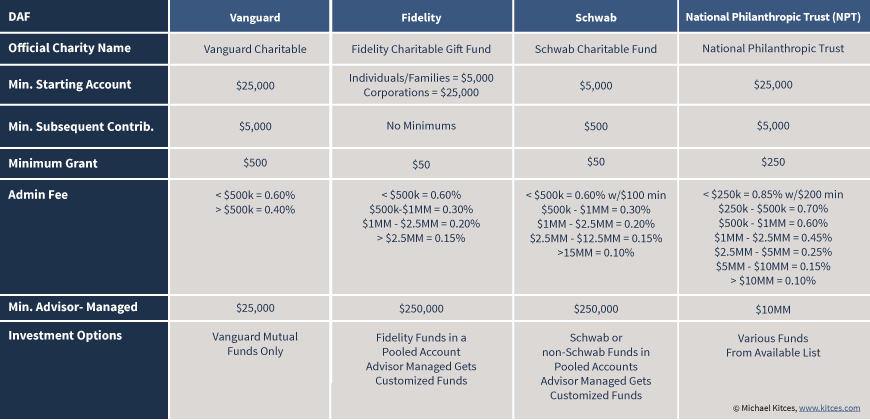

While the general approach of donor-advised funds is fairly standard, they do vary in details, from the minimum starting account and size of subsequent contributions to the minimum size of a grant. Donor-advised fund providers also vary in the cost of their administrative fees (which will generally be applied on top of any underlying investment costs), and whether they allow advisors to manage the DAF. These thresholds for some of the largest national donor-advised funds, including the Vanguard donor advised fund, Fidelity, Schwab, and National Philanthropic Trust, are shown below.

In addition to the large national DAF providers, community foundations (and some faith-based institutions) also offer donor-advised funds. The investment choices may not be as flexible (and in fact many community foundations pool their donor-advised fund assets to obtain access to their own institutional investment managers), but some suggest that locally-based DAFs from community foundations may better know the local charities and which organizations are most able to execute their missions with the funds contributed to them.

On the other hand, while community foundations may be more likely to know the local community charities in need of funding, it is the national organizations that tend to have the capability to handle the most ‘complex’ of assets that might be contributed to a donor-advised fund, from limited partnership interests and real estate to shares of a small business entity. For those looking to obtain a charitable contribution for the donation of a “non-traditional” or less liquid assets to a donor-advised fund, national providers may be better suited to handle the more complex transactions.

Notably, while a donor-advised fund can facilitate the transfer to another donor-advised fund (in essence, as a grant from one to another), not all donor-advised funds cooperate with outbound transfers to other DAFs (as the donor-advised fund is not required to acquiesce to the donor in all situations). As a result, if there is any concern that an initial donor-advised fund provider may not be the right fit for the long run, it is advisable to ask up front if the donor-advised fund permits transfers to other DAF providers.

Common Strategies For Donor-Advised Funds

The most common ‘strategy’ for creating a donor-advised fund is relatively straightforward – donor-advised funds are a good fit any time there’s a desire to contribute (and get the tax deduction) now, but make the actual grant to the final charity at some later date. In fact, the whole point of a donor-advised fund is to separate the timing of when the tax deduction occurs from when the charity ultimately receives the money.

Accordingly, any situation where there might be a desire to separate the timing of the two can be a relevant planning opportunity for a donor-advised fund, most commonly in situations where there is a “big income” year where (taxable) income spikes – for instance, when a major liquidity event occurs, from the sale of a business to the payment of deferred compensation or the execution of stock options.

The significance of a big income year for a donor-advised fund contribution is that, due to the AGI limits on charitable contributions, there’s simply more room to get a large charitable contribution in a year where income is high. Thus, for someone who might be planning to make significant ongoing charitable contributions – perhaps with the newfound wealth found by that liquidity event – there is a benefit to “front-loading” those contributions in a year where the entire deduction can be taken in the first place.

Example. Jerry’s income is normally about $100,000 per year, but this year he experiences a significant liquidity event due to the sale of his business, boosting his income this year to $5,000,000. Given his newfound wealth, Jerry commits to donate $500,000 to charities in the coming years (he’s not ready to choose where to donate that much money all at once), but is concerned that after his income reverts back to ‘normal’, he will be unable to claim a full charitable deduction for his future donations. Accordingly, Jerry decides to contribute all $500,000 to a donor-advised fund this year, claiming a full $500,000 charitable deduction (as that is well below the AGI limits in his current “big income” year). Jerry can then make periodic distributions from his donor-advised fund in the coming years to satisfy his charitable goals, without running afoul of the deductibility limits along the way.

Notably, a related benefit of making a contribution to a donor-advised fund in a “big income” year is that, as an ordinary income deduction, the charitable contribution itself is worth more given the higher tax bracket. In the prior example, Jerry’s charitable contribution comes in the 39.6% Federal tax bracket (plus any state income tax deduction), while waiting until the future would have only produced a tax deduction in the 25% bracket (to the extent it was deductible at all). It’s also important to note that, even at high income levels, the phaseout of itemized deductions (also known as the “Pease limitation”) does not limit the benefit of Jerry’s charitable deduction, as long as he was not already capping out the Pease limitation, as any phaseout will have already impacted Jerry’s prior deductions (not his charitable deductions at the margin).

In point of fact, the use of a donor-advised fund to offset a big income year can be so effective, the vehicle is sometimes paired together as a strategy with other significant income events as well. For instance, a contribution to a donor-advised fund might be paired with a large Roth conversion (though be cautious that above-the-line income from a Roth conversion and a below-the-line charitable deduction do not always perfectly offset!).

It’s also important to recognize that a key benefit of using the donor-advised fund – or really as a part of any charitable giving strategy – is to donate appreciated investments (e.g., stocks, mutual funds or ETFs, or even real estate or company stock) that are eligible for a charitable deduction at fair market value, effectively making any embedded capital gains “disappear” in the process. In fact, donating appreciated securities is generally still more favorable than making a Qualified Charitable Distribution from an IRA (if the rules are reinstated again). Accordingly, donor-advised funds can be an excellent vehicle to facilitate the process, both because as a public charity the charitable deduction is subject to the 30%-of-AGI limitation (as opposed to only 20%-of-AGI when contributing to a private foundation), and because many of the large national donor-advised funds can facilitate the contribution and subsequent liquidation of a wide range of investment assets beyond just marketable securities.

Donor-Advised Funds Versus Private (Non-Operating) Foundations

Of course, the reality is that the strategy of separating the timing of a charitable deduction from when the funds actually go to a charity is not unique to donor-advised funds – this is also a feature of creating a private (non-operating) foundation, that similarly can be funded up front (for a charitable deduction) and may make grants to other charities in the future.

However, the reality is that private foundations are significantly more expensive to operate (compared to donor-advised funds), may face an excise tax on investment income of up to 2% (unlike the tax-free growth in a DAF), have a requirement to distribute 5% of assets annually (unlike a DAF), and are subject to lower limitations on the tax deductibility of contributions (where cash donations are limited to 30% of AGI, and donations of appreciated securities are limited to 20% of AGI).

As a result, donor-advised funds are increasingly popular as an alternative to private foundations, where the latter are only used in circumstances where it is truly ‘necessary’ to do so – such as making grants to individuals in permitted situations, retaining greater control over investments/assets, a desire to compensate people [including family] for their involvement in the foundation, etc.

Other Reasons To Set Up A Donor-Advised Fund

Notwithstanding the general concept and approach of using a donor-advised fund to separate out the timing of a donation for tax purposes from when the assets ultimately go to the charity, the reality is that the mechanics of the donor-advised fund vehicle allow it to be used in other charitable giving situations as well.

A few other situations in which a donor-advised fund might be useful include:

- Conduit for appreciated stock donations. In some situations, the goal may be to donate appreciated securities directly to a charity, but smaller charities often don’t have the accounts and infrastructure established to receive in-kind donations of investment assets in the first place. Accordingly, a donor-advised fund could be established as a “conduit”, where the appreciated securities are donated to the donor-advised fund, which liquidates the investments (tax-free at that point), and then subsequently makes a cash grant out to the intended charity.

- To anonymize gifts. Some donors wish to make contributions on an anonymous basis, whether because they just don’t want to be attached to the gift for donor recognition purposes, or because they’re concerned that a large public gift will lead them to being constantly solicited for more. Yet making donations anonymously can be difficult to execute, especially when in-kind donations of appreciated securities are involved, and of course receipt of a donation needs to be acknowledged for tax purposes as well. With a donor-advised fund, the donor can make the donation to the fund, and have the donor-advised fund sponsor facilitate the donation to the charity on an anonymous basis.

- Creating An “In Memoriam” Fund. Just as a donor-advised fund can facilitate anonymous donations, it can also facilitate donations “In Memoriam” to honor a specific person. This is accomplished by simply naming the donor-advised fund itself in the name of the person to be honored – e.g., “The John H. Smith Memorial Fund” – and then requesting that when grants are made, the source donor-advised fund is recognized and acknowledged as such. Since a donor-advised fund can also collect donations from multiple sources, an “In Memoriam” fund could even be the recipient of “gifts in lieu of flowers” for someone who recently passed away (though be cognizant of minimum starting and subsequent contribution limitations).

- Teaching Charitable Giving To Children. Another ‘alternative’ use for a donor-advised fund is specifically to teach responsible giving habits for children. For instance, a donor-advised fund might be established, and the decision about how much in grants to give and to which organizations would be made collectively by the family. For those families who want to teach about responsible giving, this provides a mechanism for charitable giving to be supported in a ‘supervised’ manner while still allowing for the whole family to be involved. And when the funds are already in a donor-advised fund – so there’s no chance it’s going to go to anyone in the family as an inheritance anyway – it becomes easier to have a constructive conversation about targeted charitable giving.

- A Legacy Family Giving Vehicle. In addition to using a donor-advised fund to teach children about charitable giving while alive, a donor-advised fund can also fund as a legacy family giving vehicle after death. The virtue of doing so is that all funds that are inside the donor-advised fund can grow and compound tax-free indefinitely to support future family charitable giving. Accordingly, a donor-advised fund might be the charitable beneficiary under the decedent’s Will or Revocable Living Trust (or as an IRA beneficiary), if the decedent wants certain assets to go to charity (e.g., as a charitable bequest, or perhaps for any amounts above the estate tax exemption that would be taxed at 40% anyway) but wants to leave heirs the flexibility to decide which charities will receive the money and allow for tax-free growth along the way. Similarly, a donor-advised fund could be used as the ultimate charitable beneficiary of a charitable remainder trust, if there’s a desire to establish one now but the donor/grantor is not certain what charities to name for a bequest that might not be coming for decades.

- Evaluate A Charity’s Fiscal Responsibility Over Time. One of the real challenges for those making large charitable gifts is a fear that the charity will not use the donation responsibly. As a result, donors making significant contributions often have an interest in spreading the contributions out over time, affirming that the charity is continuing to use the funds appropriately and responsibly before making the next gift. However, in situations like “big income years” it is not feasible to stretch out charitable donations over time, as gifts in subsequent years will face the charitable deduction limitations. Accordingly, for those who plan to make gifts over time, but want to evaluate the charity’s stewardship of the funds, a donor might “front-load” the entire planned contribution into a donor-advised fund – to claim the tax deduction in the big-income year when it’s feasible to do so – and then make the subsequent donations to the charity as the charity continues to execute responsibly. If the charity slips up, the donor has the flexibility to redirect subsequent gifts from the donor-advised fund to another charity.

Of course, the important caveat to remember in all donor-advised fund strategies is that once funds go to the donor-advised fund, they must go to some charity, and cannot be retracted for the donor! The charitable gift to a donor-advised fund is still irrevocable, even if the assets have not yet passed through to the underlying charity. Nonetheless, for those who are ready to make the charitable donation – and want to receive the tax deduction now – the donor-advised fund serves as a useful vehicle to execute charitable giving strategies over time. And it certainly doesn’t hurt that any growth along the way will ultimately accrue tax-free for the charity as well!

So what do you think? Have you ever used a donor-advised fund with clients? Have you employed some of the strategies discussed here? How do you frame the donor-advised fund conversation with clients?

Thanks for a thorough review, as usual. I’m the Endowment Chair at my synagogue and looking at DAF’s as a strategy to encourage more commitments today. Planning to pull together an educational piece for this audience.

Now this may be different with synagogue’s than christian churches, but I’m going to give you a winner tip.

You should create a nicely designed card that says “I donated online” or “I donated through my donor advised fund” for your tray/basket that goes around the synagogue.

See some people don’t feel right about being the person who didn’t put anything in the basket when it comes around. That can detract from peoples desires to contribute via merchant processing, DAF, etc. because that is a substitute for the basket. Give them something to put in and they’re more inclined to do it.

But more importantly for you (the synagogue) is that those cards are the best form of advertising for DAF, merchant processed, etc. donations which I understand typically produce larger and more consistent church revenues.

I learned this from a person who works at merchant processing firm focused on religion organizations in Minneapolis (don’t remember name) and he was the inventor of this card that the merchant processor furnished to the church’s, etc. that were it’s customers. He said it was by far the most successful marketing piece they had ever done (and it’s so subtle).

Good article as always Michael! We’ve used DAFs in conjunction with NUA stock to get a double bang for your buck. Though the IRS has been silent on this there are PLRs saying it’s okay.

DAFs are the best thing mankind created since Roth IRAs and Roth IRA AGI workaround loopholes.

I’ll add that QCD’s aren’t eligible to be sent to a Donor Advised Fund, but…

A donor advised fund can be named beneficiary of an IRA which is exactly how any person should set up charitable planning.

Don’t fund the DAF to an amount that would carry past 70.5 (unless it’s a really big year) because QCDs (if still around) are the better option and then any legacy charitable interests should be from IRA to DAF at death with heirs being appointed as the new people to make grant recommendations.

I don’t see any mention of the opportunity to increase total tax deductions, if you normally claim the standard deduction. The amounts are not large, but they can add up if your income is not too high, you don;t have a mortgage and live in a state with a low state tax,

Thanks for your informative piece about donor advised funds, Michael. I’ve assisted a majority of my clients to establish their DAFs–through Fidelity, Vanguard, Schwab, national religious foundations, and local/regional community foundations. They accomplished charitable goals along with many of the other great objectives you outlined. I personally started my first DAF in the mid 1980s before I was a financial planner. I believe this modeling through the years encouraged my clients to follow a real example.

Last year I established the “Kathleen Moore Rehl ‘Moving Forward on Your Own’ Family Foundation” through my local community foundation. (A substantial portion of my speaking and book sales income goes there to fund grants for other nonprofits that benefit widows and their children.) This approach provides many of the advantages of a traditional family foundation without most of the drawbacks. For example, the initial contribution level was only $100,000.

I have also seen strategies very similar to the DAF that allow for the contribution of non-voting company shares into a non-profit account. They allow you to get a deduction on the original contribution and to retain management oversight. Net profits and distributions would flow into the charitable account. They also allow for the sale of the company shares without realizing capital gains.

Don’t forget that when donating vehicles whose book value is in excess of $5,000, some charities will actually pay the donor a proportion of the sale proceeds in cash. It’s a common but mistaken assumption that all of the sale proceeds must go down on the tax return. Note that the official receipted amount (completed on form 1098c) must be the difference not taken in cash. If you sell your classic car for $10,000, for example, and you agree with the charity that they will be pay you $2,500 in cash, only $7,500 can be claimed as a tax credit.I used to have big problems with donating vehicle tips, but am getting in better mind now. Here’s a good site I found that really helped. It gave me great methods and and showed me what I was doing wrong before…there’s even lots of free articles on the site…http://donatingvehicletocharity.com

What about nonprofits that say they operate DAFs such as Network for Good and JustGive. They are not national charities like Fidelity or Schwab or community foundations, yet they state they operate DAFs. How can this be? Can any nonprofit or foundation be a sponsor organization to a DAF or is it restricted?

Is it possible to transfer from one DAF to another DAF? For example, if someone wanted to change who holds the funds (for any number of reasons – fees, investment options, timing or flexibility of distributions) would a donor have to just empty and account and start fresh with a new account, or could a balance from the first account be transferred to the new, second account?

Yes, it would be a grant/gift from the 1st DAF to the second

For those really interested in donor-advised funds I’d encourage you to check out this podcast episode that dives deep into how nonprofits can best work with donors that are using DAFs – https://imarketsmart.com/donor-advised-funds-episode-12/

I co-host this podcast and think it is one of the best episodes we’ve done and really dives deep into this topic.

This is a great resource. Thanks for pulling all this together. Has there been any material changes in the amounts or new entities offering DAF?

Question: If you transfer assets into a DAF but do not take a tax deduction in that year, what happens? Can the individual spread the deduction over multiple years? What is several years later they discover they never took a deduction on the initial amount? Is the appreciation of shares during this time also tax deductible? Thank you!

Quick/free/not professional advice answers to your questions:

a) Nothing happens, you don’t get a tax deduction.

b) If you exceed the deductibility, you can carry that forward to subsequent years, in which you’ll have to be itemizing to take advantage of it.

c) You could file amended returns if you find you missed something you had coming.

d) Once you give to a DAF, it’s not yours, so no, subsequent appreciation is not deductible to you.