Executive Summary

Pre-tax assets like IRAs can face a significant income tax burden as their value grows, a challenge that is only made worse for those who are subject to estate taxes on those assets as well. In the extreme, the combination of the two can consume the majority of the value of an inherited IRA bequeathed to a beneficiary.

To help mitigate the combined income-and-estate-tax effect, the Internal Revenue Code allows for an “Income in Respect of a Decedent” (IRD) deduction under Section 691(c). Claimed by the beneficiary of an inherited IRA to the extent of any estate taxes that were caused by the account, the deduction can be material – as much as 40% of the value of the account!

Yet despite its size, beneficiaries in practice often “miss” the IRD deduction, not realizing it was there to claim, or perhaps “losing track” of it when changing accountants or tax preparation software. Fortunately, an amended tax return can be filed to claim a missed IRD deduction from recent years – but only the past 3 years. Which means going forward, anytime an inherited IRA appears with a new client, a good best practice for all advisors is to ask: “did the decedent who left you this account pay any estate taxes?” and if so, be certain the IRD deduction is claimed properly!

And notably, in the end the IRD deduction applies not only to inherited IRA accounts, but also other employer retirement plans, inherited non-qualified annuities, employer non-qualified stock options, deferred compensation, employer NUA stock, and more!

How The IRC Section 691(c) Income In Respect Of A Decedent (IRD) Deduction Works

To understand the purpose of the IRC Section 691(c) income tax deduction for “Income in Respect of a Decedent” (IRD), it’s perhaps easiest to illustrate by looking at what would happen if the rules did not exist.

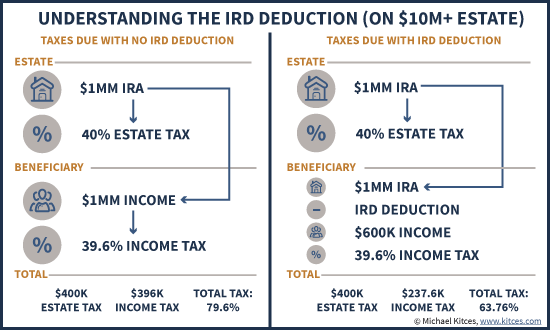

Example 1a. An affluent individual has nearly $10M of net worth, including an IRA worth $1M. Being over the estate tax exemption amount for an individual (currently $5.43M in 2015), this individual will face an estate tax liability of 40% on the last several million dollars of net worth, including the IRA as a part. In addition, when the IRA is subsequently inherited by the next generation heirs, it is still a pre-tax asset that will be subject to ordinary income tax rates as high as 39.6% as the account is liquidated. The end result: at the margin, as much as 79.6% of the IRA may be diminished by a combination of income and estate taxes.

Notably, in such situations where both income and estate taxes can apply to the same account, the combined rates have been even worse in the past. For instance, back in the 1990s, the top estate tax rate was 55% and the top income tax bracket was 39.6%, leading to a combined tax rate of 94.6%! And if either income or estate tax rates rose enough, the total tax liability could potentially exceed the entire value of the IRA in the first place!

Accordingly, the purpose of the IRD deduction under IRC Section 691(c) is actually to avoid this stacking “double” taxation effect, by providing that after death the beneficiaries who inherited the IRA will receive an income tax deduction for any additional estate taxes that were caused by that pre-tax asset.

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example, since at the margin the $1M IRA caused $400,000 of estate taxes (at the 40% marginal estate tax rate), the beneficiaries will be eligible for a $400,000 income tax deduction when the IRA funds become taxable as they are subsequently withdrawn from the account. Given this deduction, the beneficiaries will only end out owing income taxes on $1M - $400,000 = $600,000 of the IRA. Which means even at a top 39.6% tax rate, the beneficiaries will only face $237,600 of income taxes on the $1M inherited IRA, or a marginal rate of 23.76%. The end result – thanks to the IRD deduction, the $1M IRA is “only” diminished by 40% + 23.76% = 63.76%, not the 79.6% that would have resulted by just adding the two taxes together.

While the net tax liability of being subject to income and estate taxes can still be significant, the impact of the IRD deduction is that it prevents the total taxes due from ever exceeding the value of the account. After all, in the extreme if the estate tax rate was 100%, then the entire $1M IRA would be consumed by the estate tax, the beneficiaries would be eligible for a $1M IRD deduction, which means there would be zero income taxes due in the end. More generally, with any combination of income and estate taxes, the fact that the income tax exposure is reduced by any estate taxes paid ensures that the sum of the two can never exceed 100%.

How To Claim The 691(c) IRD Deduction As An IRA Beneficiary

The IRD deduction is claimed by the beneficiary of the IRA, at the time that distributions occur from the IRA (this ensures that the deduction applies at the same time that the IRA becomes taxable in the first place). And the deduction applies regardless of whether any of the IRA is actually used to pay the estate’s tax liability. In other words, it doesn’t actually matter whether the IRA is used to pay any estate taxes; the mere fact that its existence caused additional (Federal) estate taxes will generate an IRD deduction.

When the IRD deduction applies, it is claimed as a miscellaneous itemized deduction on Schedule A, but one that is not subject to the 2%-of-AGI threshold that applies to other miscellaneous itemized deductions. The fact that the IRD deduction is not subject to the 2%-of-AGI threshold also means it is not treated as an AMT adjustment.

To calculate the amount of the deduction, Treasury Regulation 1.691(c)-1(a)(2) stipulates that the decedent’s Federal estate tax liability should be calculated twice – once including all assets in the estate (as would normally be done), and then a second time including everything except the pre-tax assets like the IRA. The difference in estate tax liabilities between the two is the IRD deduction. Notably, the IRD deduction is calculated based only on Federal estate taxes, and not any state estate tax liability.

Example 2. Decedent’s estate had a gross value of $10M, including a $1M IRA. After all deductions, the net taxable estate was $9.5M. Given the current estate tax tables in effect, a $9.5M taxable estate would be subject to a tentative estate tax of $3,745,800, and after the $2,117,800 unified credit would lead to a final estate tax of $1,628,000. To determine the IRD deduction, the decedent’s estate tax is then recalculated without the $1M IRA, which would result in an $8.5M taxable estate, a tentative estate tax of $3,345,800, and a final estate tax of $1,228,000. Accordingly, the IRD deduction would be $1,628,000 - $1,228,000 = $400,000.

As the above example shows, the process of calculating the IRD deduction ensures that the IRA is treated as the “last” asset taxed at the highest marginal rate, which produces the most favorable IRD deduction. Even though the IRA was 1/10th of the total estate, the IRD deduction was not 1/10th of the $1.628M estate tax liability (which would have been only $162,800); instead, it was a full 40% of the IRA’s value, or $400,000. Pre-tax assets in the estate are always treated as the last marginal dollar subject to the highest marginal rate with the IRD deduction.

Given that the IRD deduction is literally calculated by determining the amount of estate taxes due with and without the IRA (and any other pre-tax assets in the estate) – where the difference is the amount of the deduction – this also means that an IRD deduction is only possible in situations where there was a Federal estate tax in the first place. If the estate is small enough to not be subject to any Federal estate taxes (i.e., the unified credit is sufficient to offset any taxes due), or alternatively owes no estate taxes thanks to the marital deduction or a charitable deduction (or any other valid deductions), then there is no IRD deduction either.

Notably, in the event that the IRA had “basis” in the form of after-tax contributions, that portion of the account will not generate an IRD deduction, because it was not actually a pre-tax asset in the estate. Only the remainder of the account – the pre-tax contributions, and all the growth, that would be taxable as ordinary income when withdrawn – would be eligible to generate an IRD deduction. Again, the whole point of the IRD deduction is that the asset must have actually been income with respect to the decedent in the first place, not just a return of the decedent’s principal.

Tracking The 691(c) IRD Deduction Over Time On A Pro-Rata Basis

As mentioned earlier, the IRD deduction applies regardless of whether the decedent’s estate taxes were actually paid from that IRA, or with other assets; the mere fact that the IRA caused a greater estate tax liability is sufficient to trigger the rules.

However, the IRD deduction itself can only be claimed by the beneficiary as the IRA is actually liquidated and the income tax event is triggered. This ensures that the tax deduction (the IRD deduction) is always properly matched to the taxable income (withdrawals from the IRA) that triggered it. And if only part of the account is liquidated, only a commensurate pro-rata portion of the IRD deduction goes with it.

Example 3. Continuing the earlier examples with a $1M inherited IRA eligible for a $400,000 IRD deduction, if the beneficiary takes out $200,000 of the account (20% of the total IRA), then an $80,000 IRD deduction goes along with it (20% of the total IRD deduction). The IRD deduction is claimed on a pro-rata basis as partial withdrawals occur from the IRA.

In essence, this pro-rata treatment is simply a reflection of the fact that each dollar of the $1M IRA caused $0.40 of estate taxes (at a 40% rate), and thus each dollar of the IRA has a $0.40 IRD deduction attached to it. Thus, if only a portion of the dollars come out of the account, only the share of IRD specifically attached to those dollars comes with it. Again, this also ensures that the amount of IRD deduction is always properly aligned to the amount of the pre-tax asset that created it.

On the other hand, the rules are somewhat more complex (or really, ambiguous) if the IRA is liquidated over time, as IRC Section 691(c) and the supporting Treasury Regulations are actually silent when it comes to the proper way to allocate the IRD deduction when the inherited IRA account balance includes subsequent growth that occurred since it was inherited.

Example 4a. Continuing the example of the $1M inherited IRA, imagine for a moment that in the first year after the IRA is inherited, a dramatic bull market surge lifts the value of the account by 20%, up to $1.2M. At the end of the year, the beneficiary wishes to take a $100,000 withdrawal. But it’s no longer clear how to calculate the IRD deduction, since the IRD itself is essentially attached to “just” $1M of the now $1.2M account balance. If $100,000 comes out of the account, is the proper IRD deduction still $40,000? Or if $100,000 is “just” about 8.9% of the account, does that mean the beneficiary can only claim 8.9% x $400,000 = ~$35,600 of the IRD deduction (which would mean the withdrawal is assumed to be a pro-rata blend of original IRD assets and subsequent growth)?

Although the IRS and Treasury have yet to provide any guidance on the issue, leading estate planning attorney Christopher Hoyt suggests that the ‘best’ (and most common practice) way to allocate the IRD deduction is on a FIFO (first-in first-out) basis. Such an approach is technically the most favorable for the beneficiary – it accelerates the IRD deduction to come out first and the fastest (since the IRD dollars tied to an IRD deduction are presumed to be the first out) – but realistically FIFO is also the simplest and easiest to track, manage, and substantiate in the event of an audit. After all, treating the IRD dollars (and the associated 40%-of-that-amount IRD deduction) as coming out on a FIFO basis means there’s no need to actually track all the subsequent growth in the IRA from year to year after the original owner’s death. Instead, the only amounts that are necessary to track are the original amount of IRD assets (and the associated IRD deduction), the amount that has been actually withdrawn (and the associated IRD deduction), which can then be used to calculate what’s still remaining to claim.

Example 4b. Continuing the prior example further, if the beneficiary claimed the IRD deduction on a FIFO (first-in first-out) basis, then the $100,000 distribution would allow for a $40,000 IRD deduction. After that distribution occurs, the remaining account balance would be $1.1M, the remaining IRD assets would be $900,000, and the remaining IRD deduction would be $360,000. In each subsequent year, additional withdrawals would further reduce the $900,000 of IRD assets, and each withdrawal would be attached to a 40%-of-that-amount IRD deduction, until eventually all the IRD assets and IRD deduction have been withdrawn.

Notably, by following the FIFO approach, in situations where the beneficiary chooses to stretch the inherited IRA (assuming required minimum distributions are taken in a timely manner), there will come a point where dollars remain in the account, but the entire IRD deduction has been exhausted. For instance, just continuing Example 4b above, if the beneficiary continued to withdraw $100,000 per year, a $40,000 IRD deduction would come out every year, and in 10 years the entire IRD deduction would have been exhausted, even though an account balance remains for all the growth that occurred in the account after it became an inherited IRA.

Filing An Amended Return On Form 1040X To Claim A Missed 691(c) IRD Deduction

While the IRD deduction can be quite large – a tax deduction as much as 40% of the value of an IRA(!) – it is missed surprisingly often by beneficiaries, who are simply not aware of the rules and that they should be claiming the deduction. In some cases, a beneficiary might also miss an IRD deduction by failing to realize that the decedent who bequeathed the asset was subject to estate taxes (which is necessary to create an IRD deduction in the first place). In other cases, an IRD deduction may have even been claimed for a period of time, but then the beneficiary changed accountants, changed tax preparation software, etc., and ‘lost track’ of the ongoing IRD deduction and failed to claim it in recent years.

Fortunately, to the extent that the missed IRD deduction occurred recently, a beneficiary can still go back and file an amended return within the statute of limitations – generally, you have 3 years from the date you filed your original return to file a Form 1040X amended return – to claim the deduction, and receive any tax refund that may be due for the prior year(s). Given the sheer magnitude of the IRD deduction, this is often quite desirable to do so if the IRD deduction was missed in the first place!

For advisors working with clients who have inherited assets, asking about the IRD deduction can uncover significant tax savings opportunities. As a general practice, any time an “inherited IRA” or “inherited [non-qualified] annuity” are involved, it’s a good idea to ask if the original owner had paid estate taxes at the time the asset was bequeathed – and if so, it’s time to check to see if the IRD deduction is being claimed!

Deferred Annuities, Deferred Comp, NUA, And Other Assets Eligible For 691(c) IRD Deduction

While the IRC Section 691(c) IRD deduction has been described here in the context of an inherited IRA, in reality it can apply to anything that was – as the name suggests – “income in respect of the decedent.” In other words, anything that represented an unrecognized ordinary income gain in the hands of the decedent at death, is generally eligible for IRD treatment.

Accordingly, just a few of the “other” types of assets that can be eligible for IRD treatment include:

- 401(k), 403(b), profit-sharing, and other (pre-tax) employer retirement plans. While this article has discussed IRD in the context of an IRA, in reality any pre-tax retirement account is eligible for IRD treatment. This includes any of the typical employer retirement plans, from a 401(k) and/or an associated profit-sharing plan, to a 403(b), or even a pension that has some remaining value at death (though a pension payable to a spouse would generally be offset by a marital deduction anyway).

- Deferred compensation, unpaid bonuses, and a final paycheck. Ordinary wage income attributable to employment – income had been earned but not paid (as well as earned-but-not-paid in a self-employment context, e.g., as “receivables”) – is also income in respect of a decedent, and thus able to generate an IRD deduction. Although in practice a final paycheck often isn’t ‘significant’ relative to the size of an estate (at least over the $5.43M exemption amount) that generates an IRD deduction, deferred compensation and unpaid bonuses can potentially be much larger and more material. Accrued vacation/sick leave that is paid out as wages at death would also be included as IRD, and can in some cases be a more material amount.

- Employer non-qualified stock options. If the employer had granted non-qualified stock options that were vested but not exercised, the unrealized gain on the options – generally, the excess of the fair market value of the stock over the exercise price, or the ‘bargain element’ of the option – is eligible for IRD treatment. Notably, the Incentive Stock Option (ISO) version is generally viewed as not being eligible for IRD treatment, because the ISO can be held for capital gains treatment and the only gain in the year of exercise is for AMT purposes but not IRD-triggering-ordinary-income.

- Gains in a non-qualified deferred annuity. As with an IRA, a non-qualified annuity is also a pre-tax asset, at least to the extent of any gains that are being deferred and are not yet recognized. Notably, though, this only applies to the gains portion of the deferred annuity, as the cost basis portion is not taxable (and therefore not eligible for IRD treatment) in the first place. In the case of a qualified annuity (i.e., held inside of an IRA), the entire account will be eligible for IRD treatment simply because it is a retirement account, regardless of the presence of the annuity.

- Accrued investment income. Investment income that was accrued at death but not yet paid can be eligible for IRD treatment. This might include accrued-but-unpaid bond or CD interest, or dividends from stock that had gone ex-dividend before the date of death but where the actual dividend payment date wasn’t until after death.

- Installment sales. Although property eligible for capital gains treatment is generally eligible for a step-up in basis at death and not treated as IRD property, ongoing payments from an installment sale may be IRD, where the sale itself occurred before death but installment payments (including accruing interest) will continue to be received after death. Of course, in the case of a self-cancelling installment note (SCIN) where payments end at death, there would be no IRD as no payments remain to be paid to a beneficiary after death.

- Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) stock. Another exception for the rules otherwise applicable to capital gains treatment, employer stock that was distributed from an employer retirement plan under the Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) rules is not eligible for a step-up in basis, and instead is treated as IRD under Revenue Ruling 75-125. Notably, only the actual embedded gains at the time of the NUA distribution are treated as IRD; any subsequent gains between the time of distribution and the date of death are ‘normal’ capital gains, eligible for step-up in basis and not IRD.

- Non-qualified Roth distributions. In the case of a Roth IRA or designated Roth account under an employer retirement plan, there will generally not be any IRD treatment, as Roth distributions are tax-free and not subject to ordinary income tax treatment (and therefore would have no ordinary income to which an IRD deduction would be attached). However, in the event that the Roth in the hands of the decedent fails the 5-year rule for qualified (tax-free) Roth distributions, gains do become taxable as ordinary income, and any portion of the gain attributable to the time period before the decedent passed away would be IRD. Notably, by definition this means that the IRD treatment would only be associated with gains from a relatively small number of years, and will be a moot point if the beneficiary simply holds the Roth long enough to satisfy the 5-year rule even after the decedent passed away; nonetheless, in situations where a beneficiary inherits a Roth and the 5-year rule is not satisfied, IRD treatment is at least possible to partially offset the ordinary income from a non-qualified distribution.

On a final note, it’s also worth recognizing that under IRC Section 1014(c), any asset that is income in respect of a decedent will not be eligible for a step-up in basis at death (this is why IRAs, annuities, and other similar assets do not get stepped up at death)!