Executive Summary

The decision of whether to delay Social Security benefits is a trade-off: give up benefits now, in exchange for higher payments in the future. If the higher payments are received for enough years – dubbed the “breakeven period” – the retiree can more than recover the foregone benefits early on, even after adjusting for inflation and the time value of money.

With couples, however, the decision to delay is more complex. Earning delayed retirement credits can not only boost an individual’s own retirement benefit, but increases the potential survivor benefit as well… which means the breakeven can be reached as long as either member of the couple remains alive long enough! Which makes delaying benefits even more appealing, as the odds of at least one member of a couple remaining alive is better than the single life expectancy of either member in particular.

However, delaying retirement to generate a larger survivor benefit is a moot point if the survivor already has a larger benefit of their own. In fact, a higher-earning spouse makes it less valuable to delay at all, as the other person’s survivor benefit may overwrite the delayed benefit altogether, and thus the couple loses if either member of the couple passes away too soon!

Which means ultimately, the ideal strategy for most couples is for the higher-earning spouse to delay as long as possible (which benefits them as long as either remain alive) but to start the lower-earning spouse’s benefits as early as possible, as delaying both is only beneficial in the less likely scenario that both of them remain alive into their 90s and beyond!

(Michael's Note: Some Social Security claiming strategies discussed in this article have been materially impacted by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, which has eliminated most forms of the File-and-Suspend strategy. See "Congress Is Killing The File-And-Suspend And Restricted Application Social Security Strategies" for further details.)

The Breakeven Period For Delaying Social Security Retirement Benefits

For those who don’t yet want or need their Social Security retirement benefits at full retirement age, the Social Security system allows individuals to delay their benefits and earn an 8%/year “delayed retirement credit” instead. This is often described as an “8% guaranteed return” for delaying Social Security benefits, although in reality the benefit of delaying is not quite that significant – for the simple reason that while benefits may increase by 8% for every year the retiree waits, that also means the retiree doesn’t get any money for that year!

Accordingly, the proper way to evaluate the benefit of delaying Social Security benefits is to view it as a trade-off, where – similar to the purchase of an annuity – the retiree gives up known dollars today, in exchange for receiving (higher) payments for life beginning at some point in the future. For instance, choosing to wait on retirement benefits from full retirement age (currently age 66 for those born between 1943 and 1954) until the maximum age 70 results in a 4 years x 8%/year = 32% increase in benefits, in exchange for the fact that no benefits will be received for those 4 years.

Example 1. Larry is eligible for a $2,000/month Social Security benefit at his full retirement age, but chooses to delay his benefits by 4 years, boosting his benefits by 32% to $2,640/month (though in reality, by the time he reached age 70, his benefits would be slightly higher, due to 4 years’ worth of cost-of-living adjustments as well). However, the decision to wait 4 years and get an “extra” $640/month will have a “cost” to Larry, in the form of $2,000/month (plus cost-of-living adjustments) he will not receive for the next 4 years.

This trade-off can be evaluated on the basis of a “breakeven period” – for how many years must Larry receive an extra $640/month to recover the four years of (lower) benefits he didn’t receive while waiting. Notably, the breakeven is evaluated not only by looking at the raw dollar amounts of benefits, but must be adjusted for the fact that the extra $640/month is an inflation-adjusting benefit increase (so the actual breakeven period will depend on how high inflation is in the future); the breakeven period must also be adjusted for the fact that by delaying, Larry could not invest that $2,000/month of benefits at some growth rate, and/or had to liquidate other investments (that no longer enjoy a growth rate) to cover his living expenses while the Social Security was being delayed.

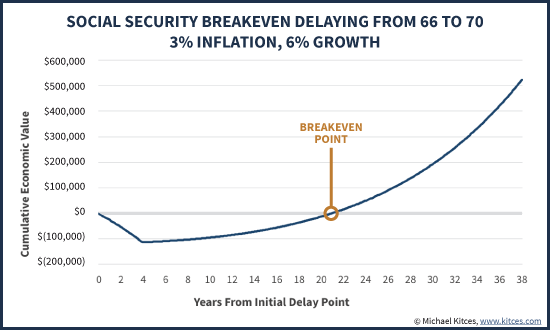

For instance, the chart above shows how long it takes Larry to break even, assuming 3% inflation adjustments and a 6% growth rate. As the results reveal, in this case Larry must live 21 years, until age 87, to begin to come out ahead by delaying. Though notably, if Larry lives beyond the breakeven period, the compounding now begins to work in his favor, and Larry can end out significantly further ahead in the long run, especially if inflation is higher than expected or portfolio returns are worse than anticipated. In fact, the implied return on those delayed Social Security dollars can beat bonds or even equities for those who live to see age 100!

Similarly, Larry might also consider whether to begin benefits early – he can start as early as age 62, which would reduce his benefits by a total of 25% given a full retirement age of 66 – which is actually simply another form of a breakeven calculation. In this case, the trade-off is whether to begin receiving benefits of $1,500/month at age 62, or get a higher benefit of $2,000/month at full retirement age, or an even higher benefit of $2,640/month at age 70. Again, the breakeven analysis will reveal how long Larry must live to recover the initial years’ worth of foregone payments with higher subsequent payments.

The bottom line, though, is that when it comes to an individual, the cost-benefit analysis of whether to delay benefits or not simply comes down to an evaluation of the individual’s breakeven period, whether he/she expects to live long enough to get past that breakeven period (given that the upside on Social Security is significant for those who live materially past that breakeven point!), and/or the extent to which the individual wants to delay Social Security as a hedge against high inflation or poor market returns.

How A Widow’s Eligibility For A Survivor Benefit Changes The Breakeven For Delaying

In the case of a married couple, the likely impact of delaying Social Security benefits can be even more favorable. The reason is that with a married couple, when one person passes away, the survivor is eligible for a widow(er) benefit equal to 100% of the deceased spouse’s retirement payments. Which means the decision to begin retirement benefits early or delay them late impacts not only the size of the retiree’s own benefit, but the size of the survivor benefit that will be payable to a spouse as well.

Thus, the benefit of delaying retirement benefits as the member of a married couple is that the higher benefit will be payable for the life of the retiree, and the lifetime of the survivor if the retiree passes away first. In other words, as long as either member of the couple lives long enough to see the breakeven period, it pays to have delayed – either in the form of a higher (delayed) retirement benefit, or a higher survivor benefit based on that delayed retirement benefit! Which means the odds of reaching the breakeven period for a couple increase significantly, as it’s no longer based on the life expectancy of the retiree, but instead on the joint life expectancy of the couple instead!

Of course, the caveat to delaying in order to earn a higher survivor benefit is that ultimately a survivor only receives the greater of the survivor benefit or his/her own retirement benefit. As a result, if both members had substantial income in the working years and will have similar retirement benefits, the higher survivor benefit is of little or no value.

Example 2. Larry is eligible for a $2,000/month benefit at full retirement age, and his wife Lisa is eligible for an even higher benefit – in fact, Lisa is eligible for the maximum individual benefit in 2015 of $2,685/month based on her work history. As a result, if Larry passes away, Lisa will not get any survivor benefit, because her own benefit is already higher than the potential survivor benefit! Even if Larry delays until age 70 – pushing his benefits $640/month higher thanks to the 32% increase from delayed retirement credits – the delay will only boost his benefit (to $2,640/month) but still will not generate any additional survivor benefit for Lisa if he passes away first, because Lisa is already eligible for more than this survivor benefit herself!

The end result – given that Lisa’s own retirement benefits will already be higher, delaying Larry’s benefits will increase only his benefits and not Lisa’s survivor benefits, and the potential for higher survivor benefits should no longer be a factor in Larry’s decision to delay. Instead, the decision of whether or not to delay benefits should be based solely on Larry’s own life expectancy and the likelihood that he will reach his breakeven point on his own.

The Problem With A Lower-Earning Spouse Delaying Retirement Benefits

As the earlier example showed, the benefit of Larry delaying Social Security benefits is limited to his own benefit, as Lisa cannot receive a survivor benefit when her own benefits are already higher. However, the fact that Lisa’s benefits are higher creates an additional complication to the scenario – it actually further reduces the benefit for Larry to delay at all!

The reason is that not only will Larry not be able to leave a survivor benefit for Lisa (because her benefits are already higher), but if Lisa dies first, her benefits will overwrite Larry’s! Which means Larry’s effort to delay his benefits may be a moot point!

Example 3. Larry decides to delay his retirement benefits until age 70 to earn 32% in delayed retirement credits. However, just before his 70th birthday, his wife Lisa passes away, and as a result Larry will begin to receive a $2,685/month survivor benefit from Lisa. And notably, Larry was going to receive a $2,685/month survivor benefit from Lisa regardless of whether he started at full retirement age or delayed until age 70. As a result, his decision to delay four years simply means he gave up four years of benefits that he will never recover, not because he passed away before reaching the breakeven period, but because his wife passed away first.

As the above example illustrates, the caveat to delaying Social Security benefits as the lower-earning spouse is that ultimately the delay only works as long as both members of the couple remain alive – Larry must remain alive long enough to reach the breakeven period, and Lisa must remain alive long enough to allow Larry to reach the breakeven period without overwriting his benefit with her own survivor amount.

Early Claiming Strategies For Spouses Anticipating A Higher-Earner’s Survivor Benefit

Notably, while there is a risk for Larry to delay benefits – given that either his death or Lisa’s death will cause him to fail to reach the breakeven point – there may actually be a benefit for Lisa to delay benefits instead.

After all, in this scenario, Lisa is the higher earning spouse, and her decision to delay benefits until age 70 will boost her benefits by 32% (in this case, from $2,685/month to $3,544/month) and will boost the amount of the survivor benefit that Larry is eligible for. After all, while Lisa won’t benefit from Larry delaying to boost his survivor benefit, Larry does benefit by having Lisa delay to boost her survivor benefit instead! If Lisa delays and then passes away first, Larry’s benefit will be stepped up from his $2,000/month up to Lisa’s $3,544/month instead, enjoying not only a higher benefit but the full additional payments that Lisa gets by delaying.

In fact, given that Lisa’s higher survivor benefit is looming, not only is there benefit for the couple to delay Lisa’s benefits – which will be valuable as long as either of them are alive (in the form of either Lisa’s retirement benefit or her survivor benefit for Larry) – but there is even less value to delay Larry’s benefits at all. Which means not only would Larry probably not want to delay benefits from full retirement age until 70, but if he had the opportunity, he would probably want to start benefits as early as possible at age 62! After all, even just “not starting early” is actually a delay (from age 62 to age 66), which has a breakeven that will be difficult to reach given that a death of either member of the couple will end the breakeven period early.

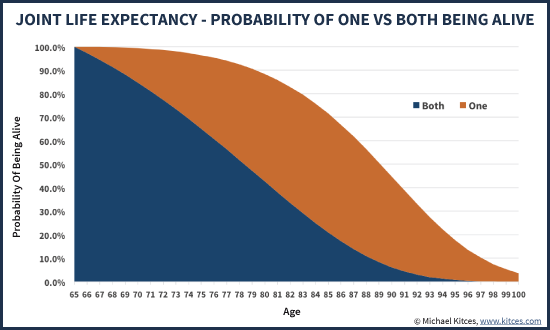

More generally, the key distinction to recognize is that when couples have substantively different benefits and are considering the breakeven periods, delaying the higher earner’s benefit will win as long as either person is alive at the breakeven, but delaying the lower earner’s benefit will only win if both of them are alive at the breakeven point.

And given that the breakeven point typically falls somewhere in the retiree’s 80s, this distinction is very significant. As shown below, the odds (based on the Social Security 2010 period life table) that both members remain alive for their 80th birthday is less than 50%, but the odds are more than 50% that at least one of them will remain alive until age 90. Which means the life expectancy of individuals versus couples is crucial; delaying the higher earner’s benefits is the odds-on bet, but delaying the lower earner’s benefit is not.

For couples who are already well into their 60s, it’s worth noting that if benefits have already been delayed (i.e., one or both didn’t already start early) and the couple is approaching full retirement age, additional strategies involving “file-and-suspend” or claiming a “restricted application” may become relevant. And in cases where there is a significant age gap, these claiming strategies can be a moot point, as there’s little potential for any coordination (e.g., where the lower earning spouse will turn age 70 before the higher-earning spouse is even eligible anyway).

Still, the point remains that with a married couple, the decision to delay benefits must be evaluated based on the life expectancy and health of both members of the couple. If both are in poor health, it still won’t pay to delay at all. And if both are in great health – and both can live well beyond the breakeven period – there can still be a value for both to delay. But for those of ‘merely average’ life expectancy, the most common strategy will be to delay the higher earning spouse as long as possible (a strategy that wins as long as either of them are alive into their 80s) but to start the lower earning spouse’s benefits as early as possible (a strategy that only wins in the less likely scenario that both of them remain alive through their 80s and beyond!).

So what do you think? How do you handle situations with married couples? Do you distinguish between the strategy for the higher-earning spouse versus the lower-earning spouse? Have you had scenarios that required a different strategy altogether?

Michael:

I fully agree with your conclusion that most of the time it never pays for both spouses to delay but rather for just the higher earning spouse to delay as the higher delayed benefit will be paid until both spouses die and thus the increase the probability to reach break-even. I also would point out that the time to reach break-even would be a little lower to reflect the fact that the higher earning spouse also can collect a spousal benefit while he / she is delaying for 4 years. This benefit is not reduced as long as the higher earning spouse is at least FRA even though the lower earning spouse is collecting a reduced benefit before reaching FRA. Also the 8% annual delayed retirement credits are not compounded and are worth exactly 32% after four years while the PIA portion of the delayed benefit not only receives COLAs but they also are compounded.

Stan, CPA

I ran Larry and Lisa in

our Savvy Social Security Planning Spousal Planning Calculator using your PIAs

($2,000 for Larry and $2,685 for Lisa) and assuming both are 62 now. I ran the

extremes: claim at 62 vs. 70; die at 70 or 90. I also ran one for average life

expectancy (85 for Larry, 87 for Lisa). As you say, it all comes down to life

expectancy. As we would expect, if Lisa dies at 70, Larry is better off

claiming at 62 so he can get those 8 years of benefits before switching to the

survivor benefit. If they both live to age 90, they are better off both

claiming at 70 and Larry taking the spousal benefit from 66 to 70.

Interestingly, I found that if they both live to the average life expectancy

(85 and 87), they are better off both claiming at 70 and Larry taking the

spousal benefit at 66. This is contrary to your findings. Perhaps you didn’t

account for the spousal benefit? In any case, this exercise points out the

extreme value in running the numbers for each individual client, as the age

disparity between spouses can change the outcome. It also points out the

importance of “life expectancy counseling”. Most baby boomers

underestimate their life expectancy. We like to ask “how long do you think

you’ll live . . . really?” and “what if you live much longer than

that?” Social Security is excellent longevity insurance and comes at a

pretty low cost – in fact, after the breakeven age it’s free. You’re only

paying for it (in the form of foregone benefits) prior to the breakeven age,

and the closer you get to the breakeven age the less it costs you. Breakeven

age, as you point out, is a function of inflation and investment returns. The

more you earn over the inflation rate, the higher the breakeven age will be.

Realistically, it would range from 78 (return matches COLA) to about 84 (3%

return over COLA). While we encourage clients to consider the very real

possibility they will live beyond the breakeven age and beyond the average life

expectancy, our main goal is to help clients understand the lifetime impact of

their claiming decisions using whatever assumptions they wish to use. If, after

counseling and analysis they choose to claim at 62, that’s their business. But

it might be a good idea to save the analysis so that if challenged by family

members later on (this happened, in a case where there was insufficient income

to pay for long-term care), it will be clear that the advisor provided proper

guidance and the client made his own decision as to when to claim Social

Security.

Michael,

Is an implicit assumption in your analysis that the lower-earning spouse has an own-benefit greater than their spousal benefit? So, if his/her spousal benefit is greater than their own-benefit, another strategy might be better–as you point out in the second to last paragraph?

Thanks,

Steve

Excellent presentation Michael! Question for you on the break even chart. Is the 6% growth rate assuming SS benefits could have been received at FRA and invested at 6%? If so, what about income taxes on the four years of SS benefits received, should not a net after tax on 85% of the FRA SS benefit be invested then at the 6% assumption? And won’t this reduce the break-even point then?

Thanks Michael.

WiseOwl,

The projection itself is tax agnostic, so no I didn’t adjust for taxes.

But that being said, if you want to assume a tax haircut on 85% of the benefits, it won’t substantively change.

You’ll get a tax-reduced payment for the first 4 years, versus a tax-reduced higher payment starting at age 70. If the tax rate is the same throughout, the net result is simply that the total amount of wealth will be reduced evenly across the board (the line will flatten), but the breakeven won’t be substantively different.

In other words, we can trade off $2,000/month for 4 years versus $640/month of extra at age 70, or pay 25% (or whatever rate) in taxes and trade off $1,500/month for 4 years versus $480/month of extra at age 70. The breakeven doesn’t change though, because we reduced both payments proportionately by the same tax rate.

– Michael

Thanks Michael, I assumed the 66 year old might still be working and thus in a higher marginal tax rate e.g. a higher effective tax rate on 85% of SS benefit received, versus a lower post age 70 marginal rate when more likely to be retired.

If the higher earning spouse is 4 years older than his spouse, and will get the max SS payout, while the homemaker spouse will get about $700 monthly at her FRA, should the lower earning spouse start taking her reduced benefit at age 62, while waiting to take her spousal benefit when she is 66 and he is 70? In this scenario he waits until he is 70 for the max benefit. If he files and suspends at 66 for him and she is 62, does it make sense for her to take a reduced spousal benefit of about $1300 minus the early percent decrease, rather than her own early benefit (700 minus early withdrawal percent)?

One aspect of this discussion not yet addressed is the desire to have more total wealth down the road. Should the “delay or not delay” decision be based on one’s life expectancy exclusively? It’s great to have a break-even point at age 86 if one delays, but in practical terms, is having more money at age 86 and > the goal of a retiree? If it is, why are we telling retirees to reduce their portfolio risk when they retire? There is a lifestyle question missing from this analysis.

Rick, thanks for this comment, though it appears there was no reply. I have been wondering if my cash flow projections had some sort of error.

I projected cash flows from current age to age 110 (Were optimists! We plan to be playing tennis when we go.). I included the sale of a second house, likely inheritances, pension, 401ks and IRAs (I haven’t yet added the RMD impacts). I want to retire at 60 yrs old. I keep finding that our total wealth last longer, grows more if we both start taking SS at 62.

I appreciate any insights you might have on common trade-offs or anomolies in planning process that might throw this off, or if you find this situation is reasonably common in practice. Thanks!

John,

It depends entirely on what you’re assuming as the growth rates on your investments over the 50+ year time horizon. If you make the growth rate assumption high enough, every possible alternative will look inferior, particularly if the model doesn’t incorporate volatility or the risk of inferior returns.

– Michael

Mr Kitces, ok, that’s embarrassing… of course, you nailed it. I appreciate you taking the time to set me straight. I’ve done pretty well with investing over the years, so even though I assumed a couple full points lower in retirement (and yes, a stable return assumption as a placeholder), it’s still a pretty strong number. When I get to the point of trying to stress test the model over a range of return assumptions, the impact should become more obvious. It’s fun to work through all this, but at some point I’ll be going to a fee-only advisor (or two) to sanity check what I’ve done. Have a great Labor Day weekend!

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/024e718dcc6b1732e40fc7bbabad3027e33d6a4fb941f7f4d1cff6f0429ca1df.gif

John,

Yeah, that’ll do it.

The real return on delaying Social Security comes in around 5%-6% real (above inflation) by your 90s. If you project returns lower than that, you should see the delayed Social Security look better in the very long run. 🙂

I hope that helps!

– Michael

If delaying to get the higher benefit at age 70 is a risk-free return, shouldn’t it be compared to alternative investments that are also risk-free? In other words, shouldn’t the growth rate be more like 3%. How much does that improve the break-even year?

Ron,

The discount rate for the analysis is based on what the client will NOT own (i.e., have to liquidate from the portfolio) in order to delay Social Security.

Yes, the risk/return characteristics of Social Security are “bond-like”. But the client isn’t SELLING a bond to ‘buy’ Social Security. The client is effectively selling the portfolio in this example (or failing to Social Security payments to invest into the portfolio, or spending from the portfolio while waiting for Social Security, which is mathematically the same thing).

The proper discount rate is the opportunity cost of not having/keeping the money in the portfolio.

– Michael

Michael, Hi, I have similar question, what if assumed portfolio is extremely conservative, say 4%, and inflation still held at 3%, would be interesting to see that scenario for comparison… as I get older my investments getting much more conservative than expected…

Thanks…

Howard S.

Retired and so far suspended for one year…

But yes, Ron, if you used a lower return assumption on the investments that would have to be liquidated while waiting for SS benefits or the opportunity cost in not being able to invest the SS benefits, then the years-to-breakeven calculation gets shorter.

Michael: Great article filled with great advice and examples. I did not see the break-even point for the lower earning spouse starting at age 62; what is that age?

Also it is tough to quantify and distinguish between “great health” and “merely average” heath. In that case, where it becomes a guessing game (this is life we are talking about), then would the bottom line strategy be to delay the higher to age 70 for all the reasons you mentioned and have the lower earning spouse begin at age 62? If so then my question above as to break-even for the lesser spouse becomes even more relevant. What do you think Mike?

Michael,

could your survivor in example 3 quickly claim all of his benefits going back to FRA if he had filed and suspended at FRA, and then claim the survivor benefit? 🙂

BlackRock actually has a nice little tool for advisors to use for free (login required). It’s simplified, but it gives a good general idea, IMO.

Michael – What about reduction of IRA before RMDs to lower tax burden? There have been a few articles re. this issue recently.

My life partner of 16 years and I have decided this question by both of us taking our respective Social Security ex-spousal benefits from 66-70 starting this year, and delaying legal marriage until after we both turn 70 in 2020. That way we can both draw partial benefits, still get 8% delayed retirement credits on our own retirement benefits, and qualify for widow benefits at 71 if either of us should die. Being able to take two ex-spousal benefits rather than one spousal benefit is one advantage of being legally single over legally married. And if circumstances change, we can always marry sooner if need be.

Looking at reality versus hypotheticals, how many folks reading this are 75 or older, and can say they are in every way more active, and healthier, than ten years ago? My father paid for great assisted living/retirement community insurance, but by the time he was in need, over age 85, he had become too stubborn and unwilling to make the life changes necessary to take advantage, living instead paying out of pocket for assistance in home care for his wife with Alzheimer’s for her last two years, then staying put until his own death two years later. Elderly affairs are a roll of the dice, financially, and dependent on the actual quality and integrity of service providers; without advocates, in survivors, offspring, or legal powers of attorney, we all become more vulnerable and inevitably funds rapidly flush down myriad sinkholes of inefficiency, if not outright swindles. Social Security funds may be the most reliable, if modest, source of income at some far point in the future (because aging voters will not let the system fail), but will not make the difference between comfort and being destitute. Habits and systems you set up now will be providing the funds that set you above subsistence level in the future, not one or two hundred a month, sooner or later.