Executive Summary

Since the income limits on Roth conversions were removed in 2010, higher-income individuals who are not eligible to make a Roth IRA contribution have been able to make an indirect “backdoor Roth contribution” instead, by simply contributing to a non-deductible IRA (which can always be done regardless of income) and converting it shortly thereafter.

However, in practice the IRA aggregation rule often limits the effectiveness of the strategy, because the presence of other pre-tax IRAs and the application of the “pro-rata” rule limits the ability to convert just a new non-deductible IRA. On the other hand, those with a 401(k) plan that allows funds to be rolled in to the plan can avoid the aggregation rule by siphoning off their pre-tax funds into a 401(k) plan, and then converting the now-just-after-tax IRA remainder.

Perhaps the greatest caveat to the backdoor Roth contribution strategy, though, is the so-called “step transaction doctrine”, which allows the Tax Court to recognize that even if the individual contribution-and-conversion steps are legal, doing them all together in an integrated transaction is still an impermissible Roth contribution for high-income individuals to which the 6% excess contribution penalty tax may apply. Fortunately, though, the step transaction doctrine can be navigated, by allowing time to pass between the contribution and subsequent conversion (although there is some debate about just how much time must pass!). But perhaps the easiest way to avoid the step transaction doctrine is also the simplest – if the goal is to demonstrate to the IRS and the Tax Court that there was not a deliberate intent to avoid the Roth IRA contribution limits, stop calling it a backdoor Roth contribution in the first place!

Mechanics Of Making A Backdoor Roth IRA Contribution Via Conversion Of A Non-Deductible IRA

The basic concept of the “Backdoor Roth IRA Contribution” is relatively straightforward. Contributing directly to a Roth IRA is restricted for higher-income individuals; once a married couple has an AGI in excess of $193,000 (or $131,000 for an individual), the maximum contribution limit to a Roth IRA is reduced to zero. However, anyone with earned income can contribute to an IRA, regardless of how high their income is; at worst, higher income levels may limit the deductibility of that IRA contribution (for those who are an active participant in an employer retirement plan), but not the ability to make the IRA contribution.

In addition, under the Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act of 2005 (TIPRA), there have been no income limits on Roth conversions of traditional IRAs since 2010. As a result, anyone who has funds in a traditional IRA – whether originally deductible or not – is eligible to do a Roth conversion. In other words, while income limits remain on Roth contributions, there are no income limits for a Roth conversion.

Thus, by putting the two together, those with higher income who are not able to make a Roth IRA contribution are able to effectively work around the income thresholds by making a non-deductible IRA contribution (permissible even at high income levels) and then converting it to a Roth (again permissible even at high income levels). (Note: In order to do an IRA contribution at all, it is still necessary to have qualifying earned income in the first place.)

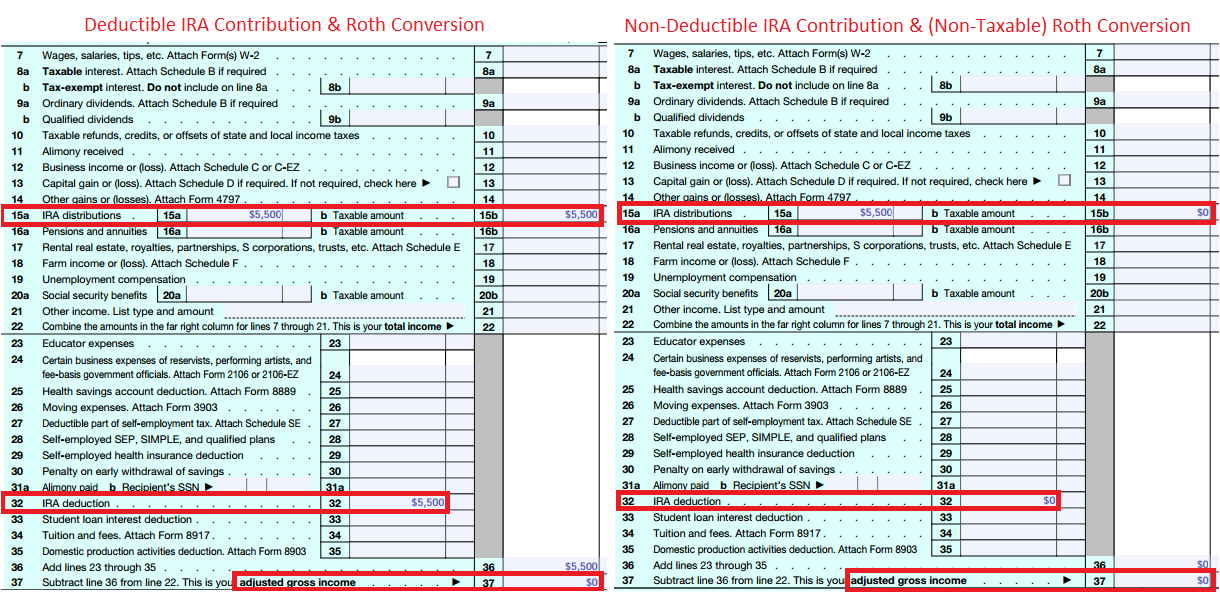

If the IRA contribution is deductible, the end result will be a contribution to an IRA that produces a tax deduction, followed by a Roth conversion that causes the income in the IRA to be recognized for tax purposes. In the end, this means there will be an IRA deduction of up to $5,500 in 2015 (reported on Line 32 of Form 1040), Roth conversion income of up to $5,500 to match it (reported on Line 15 of Form 1040), and since both are above-the-line income/deductions on the tax return, the net result is $0 of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) and a $0 tax liability, even while getting the whole $5,500 in a Roth IRA!

In the case that the IRA contribution is not deductible (e.g., because the high-income earner is an active participant in an employer retirement plan, and his/her income level has therefore made the contribution non-deductible), the net result is still the same. The contribution into the IRA itself produces no tax deduction (Line 32 of Form 1040 is $0), and the after-tax portion of the contribution is reported on Form 8606. The conversion of that non-deductible IRA is a taxable event, but the portion of the IRA that is attributable to non-deductible contributions is treated as a return of principal and thus has no tax consequences (thus Line 15a of Form 1040 is $5,500 but 15b reporting the taxable amount is $0). In the end, this means there will be no deduction for the IRA contribution, and no income from the Roth conversion of that after-tax money, and the net result again is a zero impact on AGI and a tax liability of $0, while still getting the whole $5,500 into a Roth IRA!

Ultimately then, as the above graphic shows, either way the net result is that $5,500 goes into an IRA, $5,500 ends out in a Roth IRA, and the net impact on Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) is $0, which means the tax impact is $0! The IRA contribution is always permitted (as long as there's earned income), and at that point it doesn't actually matter whether it's a deductible contribution or not, because the net result after Roth conversion is always the same - $0 of AGI, and $0 of tax liability!

Notably, though, while this strategy of making a Roth IRA contribution through the "back door" by making a (potentially non-deductible) traditional IRA contribution followed by a Roth conversion seems relatively straightforward, there are some important caveats to consider in executing the strategy.

The IRA Aggregation Rule Under IRC Section 408(d)(2)

The first caveat to the backdoor Roth contribution strategy is what’s called the “IRA aggregation rule” under IRC Section 408(d)(2).

The IRA aggregate rule stipulates that when an individual has multiple IRAs, they will all be treated as one account when determining the tax consequences of any distributions (including a distribution out of the account for a Roth conversion).

This creates a significant challenge for those who wish to do the backdoor Roth strategy, but have other existing IRA accounts already in place (e.g., from prior years’ deductible IRA contributions, or rollovers from prior 401(k) and other employer retirement plans). Because the standard rule for IRA distributions (and Roth conversions) is that any after-tax contributions come out along with any pre-tax assets (whether from contributions or growth) on a pro-rata basis, when all the accounts are aggregated together, it becomes impossible to just convert the non-deductible IRA.

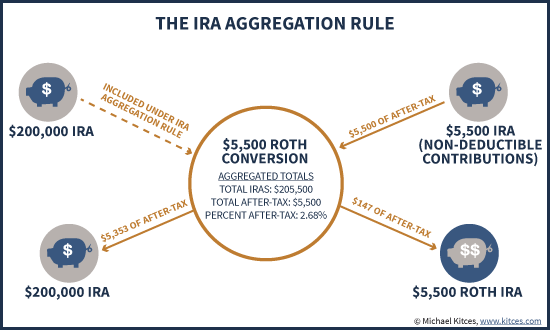

Example. Jeremy has $200,000 of existing IRA assets, accumulated from years of deductible IRA contributions plus growth when he was younger, along with a rollover from an old 401(k) plan. Jeremy is now a high-income earner, and wishes to make a $5,500 contribution to a non-deductible IRA, with the plan to convert that $5,500 into a Roth IRA.

However, due to the IRA aggregation rule, Jeremy cannot just convert the $5,500 non-deductible IRA contribution, even if it is help in a separate/standalone account. Instead, Jeremy must treat any $5,500 conversion from any account as a partial conversion of all of his IRA assets.

Accordingly, if Jeremy tries to do a $5,500 Roth conversion (from combined IRA funds that now total $200,000 plus new $5,500 contribution equals $205,500), the return-of-after-tax portion will be only $5,500 / $205,500 = 2.68%. Which means the net result of his $5,500 Roth conversion will be $147 of after-tax funds that are converted, $5,353 of the conversion will be taxable, and he will end out with a $5,500 Roth IRA and $200,000 of pre-tax IRAs that still have $5,353 of associated after-tax contributions (the remaining portion of the $5,500 non-deductible contributions that were not converted).

Notably, the net effect of the IRA aggregation rule is that only a portion of the non-deductible contributions can actually be converted, even if the non-deductible contribution is made to a new account and converted separately because the IRA aggregation rule combines all the accounts for tax purposes anyway! In fact, the IRA aggregation rule effectively “transfers” a large portion of the after-tax funds from being associated with the new $5,500 IRA over to the existing IRA instead!

Avoiding The IRA Aggregation Rule Via 401(k) And Other Employer Retirement Plans

While the IRA aggregation rule does combine together all IRA accounts to determine the tax purposes of a distribution or conversion, it’s important to note that the rule only aggregates together IRA accounts, and only the traditional IRA accounts for that individual.

Thus, a husband and wife’s IRA accounts are not aggregated together across the marital unit (although the husband still aggregates all the husband’s IRAs, and the wife aggregates all the wife’s IRAs). Nor are an individual’s own IRAs aggregated together with any inherited IRA accounts on his/her behalf. And any existing Roth IRAs – and the associated after-tax contributions that go into Roth accounts – are not aggregated either.

In addition, any employer retirement plans – e.g., from a 401(k), profit-sharing plan, etc. – are not including in the aggregation rule. However, a SIMPLE IRA or SEP IRA, both of which are still fundamentally just an “IRA”, are included.

The fact that employer retirement plans are separated out from the IRA aggregation rule means first and foremost that as long as assets stay within a 401(k) or other employer plan, they can avoid confounding the backdoor Roth strategy. Thus, in the earlier example, if Jeremy’s $200,000 IRA was a $200,000 401(k) instead, then the $5,500 non-deductible contribution to an IRA really could be converted on its own, because that would be the only IRA involved.

The second opportunity that emerges when employer retirement plans are not included in the IRA aggregation rule is that funds in an IRA can be removed from the aggregation rule by rolling them into a 401(k) or other employer plan. Thus, again continuing the earlier example, if Jeremy wanted to begin doing backdoor Roth IRA contributions, he could roll over his $200,000 IRA into a 401(k) plan, reducing his IRA accounts to zero, and then open a new IRA with a new non-deductible contribution and just convert that account.

In fact, under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(A)(ii), when funds that are rolled from an IRA specifically to an employer retirement plan, the transfer may not include any after-tax assets at all. In other words, if (under the IRA aggregation rule) Jeremy has $205,500 of total IRA assets, including $5,500 of after-tax funds, he cannot roll all $205,500 into a 401(k) plan even if he wanted to. Instead, he can only roll the $200,000 of assets that would be taxable if distributed.

In essence, this rule becomes an exception to the normal “pro-rata” rule that applies to IRA distributions and rollovers, and permits IRAs with a combination of taxable and after-tax funds to “siphon off” the pre-tax portion by rolling into a 401(k), leaving only the after-tax funds as a remainder to then be converted (and/or to receive subsequent non-deductible contributions to convert in future years!).

Of course, the most important caveat to this rule is simply that the individual must have a 401(k) plan that accepts roll-in contributions in the first place, which is not always the case. In the extreme, if the individual has any Schedule C income for consulting or other self-employment activity (and no other employees), he/she could even create an individual 401(k) and make a small contribution from income, establishing the account which can subsequently be used to accept roll-ins from his/her other IRAs to execute the strategy.

Backdoor Roth IRA Conversions And The Step Transaction Doctrine

The second potential blocking point for doing a backdoor Roth contribution is called the “step transaction doctrine”, which originated decades ago in the 1935 case of Gregory v. Helvering, and stipulates that the Tax Court can look at what are formally separate steps of a transaction that have no substantial business purpose to be separate, conclude that they are a really just a single integrated tax event, and treat it as such.

In the context of the backdoor Roth contribution, this means if the separate steps of non-deductible IRA contribution and subsequent conversion are done in rapid succession, there is a risk that if caught the IRS and Tax Court may suggest that the intent was to make an impermissible Roth contribution… and then disallow it (and potentially apply an excess contribution penalty tax of 6%), if the individual’s income was too high to qualify in the first place.

Example. Betsy earns over $250,000 per year, and wishes to make a Roth IRA contribution in 2015, but cannot because her income is too high. Instead, Betsy decides to pursue the “backdoor Roth contribution” strategy, and makes a non-deductible IRA contribution on July 1st, followed up with a conversion to a Roth IRA on July 2nd (as soon as the funds have officially been deposited in the IRA account and are available to transfer to the Roth IRA account).

The fact that Betsy did the steps in rapid succession implies that her intent all along was to complete a Roth IRA contribution that she was not allowed to make due to her income. According, under the Intent Test of the step transaction doctrine, if the IRS challenged the situation, the Tax Court may conclude that Betsy really did just make an impermissible Roth IRA contribution, which would then require her to remove the funds from the account, and be subject to a 6% excess contributions penalty tax as well.

It’s crucial to recognize that with the step transaction doctrine, each step of the transaction continues to be entirely legitimate. The point is not that each step cannot be legally done, nor even necessarily to say that they can’t be done one after the other. The ultimate point of the step transaction is that when the multiple steps are done with the clear intent of accomplishing a single transaction, though, the Tax Court can recognize (and tax or penalize) it accordingly.

Accumulating The 6% Excess Contribution Penalty Tax On Multiple Roth IRA Contributions

Notably, because the excess contribution penalty tax applies every year the contribution is not corrected, there may even be risk that a backdoor Roth contribution made in the distant past (beyond the statute of limitations) could still create issues, because while the original backdoor Roth contribution may no longer be challenged for that tax year, the subsequent years that the impermissible contribution remains in the account would still be within the statute of limitations. And arguably, if the excess contribution penalty was never reported on IRS Form 5329 in the first place, the statute of limitations may never even start on those prior years.

Thus, for instance, if someone had done backdoor Roth IRA contributions that ran afoul of the step transaction doctrine for 5 years in a row, the earliest contributions from 4 and 5 years ago might no longer be subject to penalties for those years (or might if the IRS deems failure to file Form 5329 prevented the statute of limitations from starting), but either way in the current year the taxpayer could still face penalties for each of the 5 improper contributions that still remained in the account re-creating new excess contribution penalties every year (although the most recent might still be corrected)! And if enough such penalties compound, it's even conceivably possible to trigger a 20% accuracy-related penalty as well!

Avoiding The Step Transaction Doctrine On Your Roth IRA Backdoor Contribution

So how is the step transaction doctrine avoided? In this context, the step transaction doctrine applies to a series of steps done in quick succession that have the substance of a single whole (and not permitted) transaction, such that the court determines by looking at the end result that it was the taxpayer's intent to do the single-step transaction in the first place.

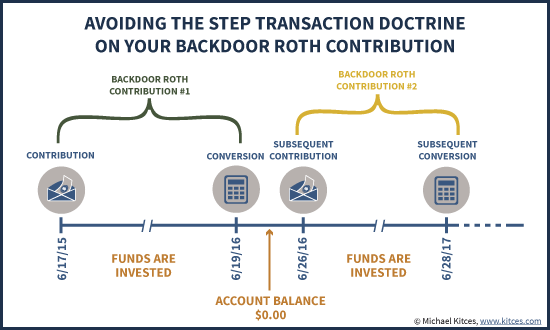

Accordingly, then, the key to avoiding the intent test of the step transaction doctrine is conceptually simple: put more time and space between the steps, to clearly establish that they were separate and independent decisions, and not part of a single whole. If there is a deliberate time gap between when the non-deductible IRA contribution is made, and when the subsequent Roth conversion occurs, it's easier to claim that the end result of dollars in the Roth wasn't part of a sole intent to circumvent the rules. Again, the reality is that each event separately is permissible, but the goal is to clearly establish that each step really is separate.

The caveat is that there's no hard-and-fast rule about “how long” it takes to avoid the step transaction. A prudent rule of thumb in the context of the backdoor Roth contribution is to wait a year (though notably, Jeff Levine and the team at Ed Slott and Company believe a much shorter time period is sufficient, such as waiting "one statement" until an end-of-month statement is released to show the IRA contribution being made). For instance, in a similar step-transaction-doctrine issue with partial 1035 annuity exchanges and subsequent liquidations (which allowed annuity owners to get more favorable treatment in the multi-step process than could have been obtained if treated as a whole), the IRS ultimately declared in Revenue Procedure 2008-24 that as long as the taxpayer waited at least 12 months between the 1035 exchange and the subsequent liquidation, it would be allowed. Thus, for example, if the current non-deductible contribution is made in June of 2015, the Roth conversion would be done sometime next June (after a full 12 months has passed).

For those who plan to do ongoing annual Roth IRA backdoor contributions, the strategy might be repeated again from year to year, where each non-deductible contribution is made, after 12 months that amount is converted (and the account balance goes to $0), and then a few days or weeks later a new non-deductible IRA contribution is made again, which in turn will be converted again another 12 months hence. This allows for a clear sequencing of cash flows, where each non-deductible contribution can clearly be shown to have had time to “age”, introducing the possibility that circumstances might have changed, and affirming that the subsequent conversion was an independent transaction.

And ideally, the funds should actually be invested during this intervening year as well. While investing the funds creates the potential that there will be a small tax liability when the conversion occurs if there was any growth along the way (if the $5,500 account grows to $5,750, the $250 of gains will be taxable at the time of Roth conversion). However, a tax liability will only occur if there was growth (which still isn’t a bad thing in the end!). And in reality, the fact that the funds were invested for growth, and had the possibility of creating a tax liability, is also what helps to reinforce that the steps were independent and not done with the sole intent of defeating the Roth IRA contribution limits as a step transaction!

But perhaps the most important to step avoid the step transaction doctrine is the simplest one: do not, in any notes or records, indicate that you are doing to do a “backdoor Roth IRA contribution” in the first place! After all, the reality is that the application of the step transaction doctrine is based on the court’s determination of intent – so when you say you are trying to do a backdoor Roth IRA to bypass the Roth contribution income limits, you are making the case for the IRS!

In addition, it’s important to note that in the case of financial advisors, client notes and records are discoverable documents if the client winds up in Tax Court! Unlike in the case of CPAs in certain circumstances, non-CPA client notes and advisor-client communication are not privileged (confidential even from the courts). Thus, advisors should also be cautious not to record in the advisor’s CRM and client file that the advisor is facilitating a backdoor Roth contribution, or risk that the advisor’s recommendation to do a “backdoor Roth contribution” is the very document used against the client to defeat the strategy!

Risk Of Getting Caught Vs Risk Of Being Penalized Under The Step Transaction Doctrine

It’s important to recognize that the step transaction doctrine is ultimately not a black-and-white test; instead, it is a nuanced interpretation of the facts and circumstances of the situation. In point of fact, this is why it has evolved as a judicial doctrine in the courts, not merely as an arbitrary rule that the IRS can apply at will.

In addition, the reality is that current reporting systems for IRA contributions and conversions generally do not track (in the automated reporting to the IRS on Form 1099-R and Form 5498) the exact days on which a non-deductible IRA contribution and Roth conversion occurred, nor from which accounts (and whether it was related to the same account). Which means the IRS has no real way to detect potentially abusive backdoor Roth contributions, short of discovering them by some other means (e.g., a random audit) and then raising the issue.

As a result, it is fair to acknowledge that the actual risk of getting “caught” with a questionable backdoor Roth contribution is low. Nonetheless, though, for someone who is caught, it may be difficult to defend that a backdoor Roth contribution was not a step transaction, if they were in fact done in very rapid succession. This is roughly analogous to speeding by driving 57mph in a 55mph zone; the odds that a police officer pulls you over are low, but if you are pulled over and end out in traffic court, you can’t really dispute that you were guilty of speeding (and at best, you can just ask for leniency on the punishment!).

On the other hand, given the dollar amounts involved, if the client is challenged, it’s almost certain in practice the client will just choose to acquiesce and pay any penalties the IRS assesses, as the cost to fight the matter with the IRS will likely be worse than just accepting the consequences and moving on. Though given that repeated years’ worth of backdoor Roth contributions could create a compounding excess contribution penalty tax (potentially even compounding enough to trigger a 20% accuracy-related penalty in the final year as well), eventually it may be the case that a client will wish to fight to defend the strategy.

However, from the IRS’ perspective, as the magnitude of dollars engaged in the strategy increases, that may also increase the likelihood that the IRS will pursue the matter in the first place. And in fact the reality that the dollar amounts involved are typically still small may indicate why the IRS has not aggressively pursued the strategy… at least, not yet?

Guide To How To Do A “Backdoor Roth IRA Contribution” Without Getting In Trouble

So in the end, what is a "backdoor Roth contribution"? A backdoor Roth IRA contribution is simply making a (typically non-deductible) IRA contribution, followed by a subsequent Roth conversion, even if you're otherwise over the income limits to make a normal Roth IRA contribution, all without running afoul of the step transaction doctrine.

Given all these dynamics, how should a “Roth IRA backdoor contribution” be accomplished? By following these steps:

How To Do A Backdoor Roth IRA Contribution Safely

- Verify there are no other pre-tax IRAs

- If there are, roll over existing pre-tax IRAs to a 401(k) (if available) to avoid the IRA aggregation rule

- Contribute to non-deductible IRA (if eligible)

- Invest funds in the non-deductible IRA

- Keep invested for 1 year (or if you're more aggressive follow the "one-statement" rule)

- Convert to Roth IRA

- Repeat steps 2-5 annually as desired

- Do not at any point along the way note that you are doing a “backdoor Roth contribution”!

It’s also worth noting that with the IRS’ decision in IRS Notice 2014-54 to allow after-tax funds in 401(k) plans to be split upon distribution (which allows after-tax funds to be converted to a Roth), a similar “deferred Roth contribution” is now possible with employer retirement plans that allow after-tax contributions as well. In the extreme, this can even be a form of “supercharged backdoor Roth” if the plan allows in-service distributions to repeat an annual contribute-then-convert process. Though again, particularly in the context of an annually repeated strategy, clients should be cautious not to trigger the step transaction doctrine.

Ultimately, it remains to be seen how long the backdoor Roth contribution will continue to be allowed. President Obama’s budget recommendations earlier this year did include, in the so-called Treasury Greenbook, a proposal that would outright prevent any after-tax funds in a retirement account to be converted to a Roth at all, which would “kill” most forms of the backdoor Roth strategies (though notably, it would still be possible if the IRA owner was not a participant in an employer retirement plan and was still making a pre-tax IRA contribution to convert).

For the time being, though, the “backdoor Roth IRA contribution” strategy does remain available… at least, as long as you don’t make it clear that’s what you’re trying to do!!

So what do you think? Are you recommending a 2015 "backdoor Roth IRA contribution” to clients to implement? Have you ever had a client who faced a challenge to the strategy? Do you plan to wait (between contribution and subsequent conversion) when executing the backdoor Roth IRA conversion strategy in the future?