Executive Summary

With interest rates hovering around multi-decade lows, investors have been increasingly concerned about the consequences to bonds when the “inevitable” shift happens and rates begin to rise. As the simple math of bonds makes clear, rising interest rates will drive down bond prices, potentially to the point of creating negative total returns for bonds.

To defend against this risk, an increasing number of advisors have been shifting to buying individual bonds in lieu of using bond funds. Given that bond funds tend to target a consistent maturity, in a rising rate environment the potential exists that bond funds will “lock in” bond price losses annually, while holding individual bonds until maturity allows for the investor to be assured that the bond will not face capital losses and will eventually mature at par value.

Yet the reality is that in an upward-sloping yield curve environment, rolling bonds to maintain a constant maturity is actually an enhancement to total return… enough that even if rates do rise, funds that roll bonds down the yield curve may still outperform the hold-to-maturity bond investor! And the steeper the yield curve becomes, the greater the benefit to sticking with bond funds after all.

Of course, the reality is that if rates spike “enough”, there is still risk that funds rolling their bonds will underperform just holding individual bonds until maturity. But on the other hand, trying to avoid rising rates by buying individual bonds is still at best a risk-return trade-off, as investors give up a “known” potential to roll down the yield curve for greater returns against just the potential that interest rates may, eventually, rise far enough and fast enough to offset the benefit!

How Individual Bond Prices Rise As They’re Held To Maturity

The “hold to maturity” approach with bonds is used most commonly as a means to manage the potentially adverse consequences of interest rate fluctuations, and specifically of rising interest rates. While rate increases can cause bond prices to decline, the potential to buy a bond at par and hold the bond until maturity ensures that, eventually, that principal will be returned intact (assuming no default), while interest payments are received along the way as well. In other words, holding bonds to maturity ensures that any price declines due to rising rates will only be temporary.

However, a unique and often under-recognized fact is that in a ‘normal’ upward-sloping yield curve environment, holding a bond until maturity actually gives up price increases that otherwise occur as the years go by. The reason is that as the bond ‘rolls down the yield curve’ – it’s remaining maturity gets shorter and shorter as the maturity date approaches – the original yield of the bond may actually look quite appealing relative to similar shorter-term bonds at that point!

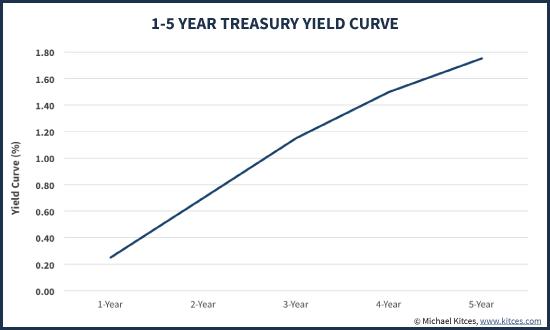

For instance, the chart above approximates today’s yield curve, where the 5-year Treasury yields 1.75%, the 4-year offers 1.50%, the 3-year pays only 1.15%, the 2-year is down to 0.70%, and a 1-year Treasury offers only 0.25%. So imagine for a moment that an investor has just bought a 5-year Treasury (for $100) with a stated coupon yield of 1.75%, and that this yield curve will remain in place for the next 5 years as the bond is held until maturity (when it will mature at par for $100).

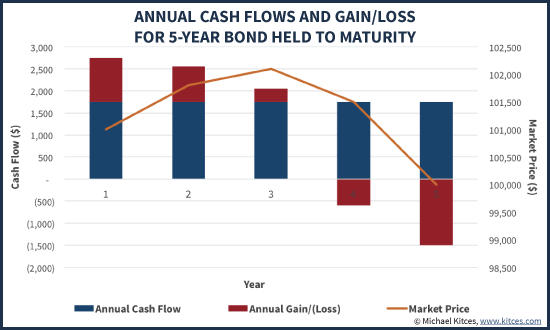

A year from now, the investor will still own a Treasury that yields 1.75%, but it won’t be a 5-year Treasury anymore. It will be a 4-year Treasury at that point. And a 4-year Treasury is only “supposed” to yield 1.50%, not 1.75%. Which means the originally-5-year Treasury’s price will actually appreciate, to about $101 – such that over the remaining four years, the bond will yield 1.75% per year, but lose $0.25 per year in price declines, allowing it to produce a yield-to-maturity of 1.50%, the same as buying a new 4-year Treasury bond at that time. In fact, this is the whole point of why bonds change price as interest rates change – to ensure that existing bonds, combining their price-change-plus-yield results until maturity, will produce the same cumulative total return until maturity as new bonds bought at then-current yields over the same time horizon.

As the bond’s maturity date continues, the bond price will continue to fluctuate to ensure its then-current yield-to-maturity matches the then-current yield curve at the time. As the bond approaches the 3-year mark, its coupon of 1.75% will be even more superior to the then-current 3-year Treasury yield of 1.15%, and the price will increase to $101.80 – which ensures that over the remaining 3 years, the ‘excess’ interest rate of 0.60% will be offset by three years of the price declining at $0.60 per year (again to produce a yield-to-maturity of 1.15%).

And so it will continue to progress as the bond’s maturity date looms even close. By the final years, the bond price will finally begin to converge on the known-to-be-$100-at-maturity price, and as the ‘excess’ yield in the final years is offset almost entirely by price declines in those final years. For instance, with 1 year to go, the original bond still yielding 1.75% will be compared to a 1-year Treasury rate of only 0.25%, which means the price heading into the final year will be $101.50 – of which $1.50 will be lost as the bond price moves to $100 at maturity.

Notably, over the whole time period, the fact remains that the bond bought at $100 will mature at $100 and produce 1.75%/year coupon payments (for a total of $8.75 in bond interest). But the implied changes in interest rates as that originally-5-year bond is compared to shorter and shorter maturity (with lower and lower interest rates) will cause the bond to temporarily appreciate before it finally converges on its $100 final value.

How Bond Investors Can Go Rolling Down The Yield Curve

The fact that bond prices will increase in the initial years after purchase (at least in any ‘normal’ upward-sloping yield curve environment) supports the popular bond strategy of “rolling down the yield curve” – where bonds are regularly sold a year or two after purchase (at a premium price), and reinvest again at the original maturity and yield… just to repeat the process again in the subsequent year.

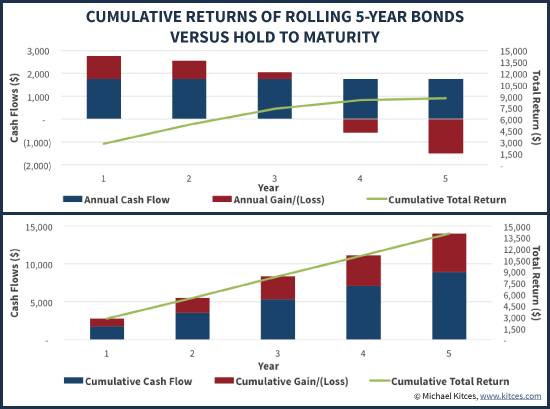

For instance, as noted earlier, with the 5-year yield at 1.75% and the 4-year at “just” 1.50%, a 5-year bond will appreciate in price from $100 to $101 after the first year – a recognize of the ‘value’ of having a four-years-remaining bond yielding 1.75% when the ‘going rate’ for a 4-year bond is only 1.50%. This provides an opportunity for the investor to sell the bond at $101, and reinvest into a new 5-year bond at 1.75% again, producing a total return in the year of 2.75% (where 1.75% is the coupon payment from the bond, and 1% is the appreciation on the bond).

Repeated annually, this can produce a significant boon to total return for a bond investor. As shown in the chart below, the cumulative coupons of just holding a 5-year Treasury at 1.75% until maturity may be $8.75 (which is simply $1.75/year for 5 years), but the cumulative return of reinvesting into a new 5-year bond at the end of each year is $13.75 over the 5-year time period (including $8.75 of cumulative bond payments, plus $1/year of bond price appreciation for 5 years).

Notably, this phenomenon of being able to trade bonds as they roll down the yield curve actually produces a natural tailwind to bond funds that are managed to produce a stable average maturity. Bond investors that hold until maturity lose out on the price appreciation in the early years, as the bond premium winds back down when the bond approaches maturity; by contrast, bond funds that continue to trade their bonds to keep moving back to the original target maturity capture an additional price return from year to year! And the steeper the yield curve in bonds, the greater the appreciation of the bond as initial years go by, and the greater the total return available by continuing to roll the bonds! (Though notably, bond trades must still be managed efficiently, or the increase in total return may be offset by bid/ask spreads and transaction costs!)

Why Bond Funds Maintaining Constant Maturity Might Not Suffer With Rising Rates

With the ongoing fear of looming rising rates, it has been increasingly popular for advisors and clients to eschew bond funds, and instead invest into individual bonds. As the convention view goes, by owning the individual bonds, investors can avoid sustained losses on their bonds by simply holding them to maturity, instead of owning bond funds that may sell their bonds (at a loss) in their effort to maintain a stable maturity consistent with the goals of the fund as stated in the prospectus.

Yet as shown above, rolling bonds with an upward-sloping yield curve actually creates wealth, which means the decision to hold bonds to maturity is actually a trade-off – the ‘good’ news is that any losses from rising rates can be recovered as the bond matures at par, but the ‘bad’ news is that doing so gives up the additional total return available from rolling the bonds instead!

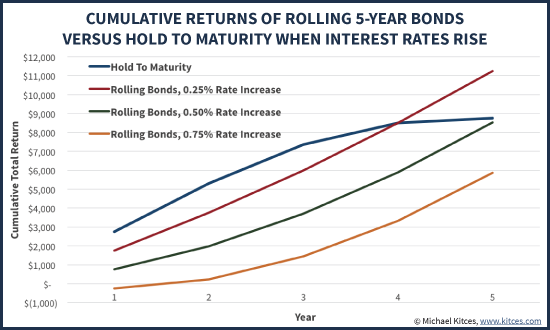

So how much of an interest rate increase does it take for the two to offset? As the graphics show below, even if rates increase an average of 0.25%/year – returning to 3% yield on the 5-year Treasury by the end of the decade – the investor still has a better cumulative return by rolling the bonds. In this case, the price decline from rising rates effectively offsets the price increase from rolling down the yield curve, but the investor still gets to keep reinvesting at higher yields, producing more total return. At a 0.50%/year rate increase – pushing the 5-year to 4.25% by the end of the decade – the scenarios come out the same, as the small annual price losses that are recognized by rolling the bonds in rising rates are offset by the higher yields obtained by reinvesting into new bonds. If rates rise at a more ‘extreme’ rate, by 0.75%/year – putting the 5-year Treasury at a whopping 5.50% by the end of the decade, a yield it hasn’t seen since the year 2000(!) – the investor still has a positive total return, at just a slight loss to the buy-and-hold investor.

As the results show, there is a point at which rising rates will make it unfavorable to hold a bond fund over just sitting on individual bonds until maturity. However, the required magnitude of rate increases must be quite significant – even a scenario where rates rise fast enough in the next 5 years to offset all the rate decreases of the past 15 years (back to 2000!) still only results in a slight loss of total return compared to just buying and holding the bonds!

Additional Factors In The Rising Rate Breakeven Of Rolling Down The Yield Curve

Notably, there are a few other important factors to consider in the implications of continuing to use bond funds (despite the potential for rising rates) over just buying individual bonds directly to hold until maturity.

Bid/Ask Spreads And Other Bond Transaction Costs

First and foremost, the issue of bond transaction costs – including both outright trading costs, and more significantly any bid/ask spread (plus dealer mark-ups) – can potentially be a drag on either strategy. For large bond funds that have scale, bid/ask spreads and dealer markups may actually be more favorable and modest than an individual investor trying to buy a few individual bonds.

In fact, given potentially limited dollar amounts, strategies to roll down the yield curve may be better suited in bond funds than for investors buying the bonds directly. On the other hand, when buying government bonds in particular, bid/ask spreads tend to be narrower and pricing tends to be better, which makes buying individual bonds for an individual investor at least somewhat less problematic.

Slope Of The Yield Curve

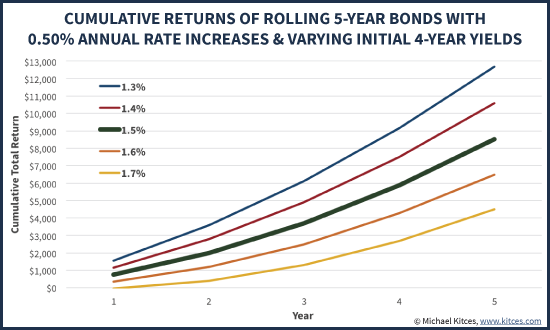

Second, it’s important to note that the actual benefit of rolling bonds along the yield curve is heavily contingent on the slope of the yield curve itself – in the case of our earlier examples of rolling a 5-year Treasury bond, the benefit is heavily driven by the exact difference in yield between the 4-year and 5-year Treasury. A 0.25% difference (from 1.50% on the 4-year to 1.75% on the 5-year) is enough to break even over 5 years even if rates go up 0.50%/year; the chart below shows how the outcomes change (with 0.50%/year rate increases) as the 4-year Treasury moves higher or lower relative to the 5-year (resulting in a spread between 0.05% and 0.45%).

Uniformity Of Rising Rates Across The Curve

Third, it’s important to note that “interest rate increases” in general does not necessarily mean that rates increase uniformly at all points on the yield curve (though that was the assumption in all the earlier examples).

For instance, just because the Federal Reserve raises rates (at the short end of the yield curve) doesn’t necessarily mean intermediate or long-term rates will rise. In fact, if short-term rates rise and long-term rates don’t (or do but to a lesser extent), the yield curve will be flatter and the benefit of rolling bonds will diminish. Alternatively, in recent months mid-to-long term interest rates have actually increased (even though the Fed hasn’t yet changed short-term rates), and the steepening yield curve has actually made it even more valuable to use constant-maturity bond funds that roll their bonds along the yield curve, rather than simply holding until maturity.

Corporate Vs Government Bonds

And fourth and finally, it’s worth noting that all the charts here were based on U.S. government bonds. Using corporate bonds will entail different yields and a different yield curve, which may be flatter or steeper than government bonds. In addition, corporate bond prices can also fluctuate as risk spreads widen and narrow in a changing economic environment, which could make the process of trying to roll bonds better or worse.

On the other hand, in the context of corporate bonds with default risk, there’s also virtue to using a bond fund over individual bonds, simply for the potential of obtaining greater diversification (unless the client’s portfolio is truly so large that an allocation of individual corporate bonds can still purchase enough different bonds to effectively diversify the individual-company risk).

In the end, though, the bottom line is simply to recognize that the decision to purchase individual bonds that will be held until maturity, rather than using a bond fund that manages to a consistent duration, can actually result in inferior returns with an upward sloping yield curve, simply by losing out on the ability to roll bonds along the yield curve. As a result, even a moderate rising rate environment could still perform just as well with bond funds as with individual bonds, and even more so if the yield curve steepens further. Of course, if rates do rise enough, it really will be better to hold individual bonds to maturity rather than a fund that rolls them… though even then, investors must weigh whether it’s better to buy individual bonds to maturity, or simply use a bond fund with a somewhat shorter duration to reduce the risk exposure, and then continue to earn the additional return potential that’s still available to a mutual fund that rolls the bonds!

Michael’s Note: Special thanks to Ryan Massey and Jason Stuck of Performance Trust Analytics Group, for their assistance on some of the bond modeling and calculations in this article!

Excellent analysis Michael, bravo!

Thanks! 🙂

Yes, very grateful for the analysis

Since the Fed works at the short end of the yield curve, wouldn’t Fed action to raise short term rates actually tend to flatten the yield curve?

It really depends on the market reaction to the Fed actions. If NOTHING else on the curve moved, yes by definition the Fed raising the short end of the curve would flatten it. But markets do react. Which frankly could flatten it even more, or cause it to remain at the currnet slope, or if the market thought the Fed was raising TOO SLOW it could even steepen as the Fed raises (as the market anticipated faster increases in the future!).

– Michael

We have three bubbles now, brought on by cheap money: housing, bonds, and stocks. When is the last time the Fed tried to engineer a “soft landing” that didn’t turn into a crash? Yes, it all depends on how the markets react, and if they read it as a trend change, they will all head for the exits at the same time. We could see Deflation and rising interest rates to extremes at the same time.

Perhaps, but a lot of people has made the exact same statement about the imminence of rapidly rising rates since the Fed’s first QE actions in 2009. And instead, rolling down the bond curve has continued to be a radically higher return strategy for 6 years…

Predicting the exact timing of a rate increase and how it will propagate across the yield curve is far easily said than done. Just noting…

– Michael

At the end of January of 2014, every talking head on the financial programs were saying the interest rates were going up. I sent out a memo to my mortgage firm that rates would be going down, and possibly challenge the 2012 lows. I was simply reading the charts, technical analysis, and they told me we’d hit the top of the long term downtrend in the TNX, and would be headed down. I turned out to be right, and the Bill Gross lost his job at PIMCO by hedging against higher rates. He should have looked at what the “tea leaves” were saying. I still think rates are going lower in the near term. And I don’t think the Fed will raise rates this year. As much as it would like to put some arrows back in its quiver, it can’t afford to, because the markets won’t react well to it.

The problems in this economy have nothing to do with interest rates or liquidity anyway, and the Fed has no control over tax or regulatory policy, which is where the problems lie. The Fed has been pushing on a rope.

Fantastically thorough breakdown of this concept, love these articles.

Thanks! 🙂

Michael:

Thank you for this great article. As a younger advisor, I have struggled lately explaining the impact of rising rates on bond funds. Do you have any advice or analogies that you like to use when discussing this topic with clients?

Thanks!

Great article Michael. The individual advisers in our firm have differing opinions on this subject, and this excellent explanation of the benefits of bond funds in certain situations will help us.

Michael, thanks for this great analysis. Re expenses, my experience is that for most retail investors, high dealer markups alone tilt the analysis in favor of inexpensive bond funds over individual bonds.

At a DFA conference last September, I chatted briefly with Joe Kolerich about bond ladders vs. bond funds. At the time I had access to individual bonds with very low dealer markups (though a TAMP) and had been putting my clients in bond ladders, but I was about to lose that access and was concerned that switching to a bond fund like DFA’s 5-Year Global would cost my clients some return. Joe claimed that a bond fund using variable maturities would actually outperform a bond ladder. Your analysis, even without specifically addressing variable maturities, seems to lend credence to that position. Thanks!

Very insightful!

It’ll be interesting to see what happens to the 10-year treasury yield once the Fed starts raising. I don’t think we’ll be going up farther than 2% (4.5%) MAX for the next decade… if not our working lifetimes. The Fed Funds could rise to 2.5% and the 10Y could stay at 2.5% like it did a decade ago, for a flattening yield curve.

Everybody freaking out about rising rates needs to just relax!

Here’s my take on rising rates and buying property if permitted: http://www.financialsamurai.com/should-i-buy-a-home-in-a-rising-interest-rate-environment/

The value of this analysis to me is to say “Hold on, folks. It’s not that simple. Follow it through and understand the variables.” In the end, it’s yet another example of “I don’t know.” And that’s fine and we should say that to ourselves and to our clients more often. About rebalancing. About tax loss harvesting. About risk. And about returns. It’s healthier for everyone.

An interesting article. Does a similar argument hold for CD ladders, and may it prove worthwhile replacing CDs before the end of their term?

Thanks,

Brian

A great article indeed!

If we are in the throes of a Wicksellian dilemma, then (slowly and moderately) rising rates may be a positive, and, in any case, panic is generally not productive.

Hello Michael

Let me start by repeating the “thank you” that I gave

to you in person at the Nor Cal FPA event after you spoke. I’m writing

you today in response to the wonderful and timely article you just released on

bonds vs. bond funds.

I will confess up front that it’s unclear to me whether I am

writing you, or thinking aloud. Either way, here it goes.

I see two prisms in which to view the issue: strategic or

tactical. Ironically, our firm (West Coast Financial in Santa Barbara)

has leaned heavily toward strategic allocations believing more in The Random

Walk. I have listened carefully to your presentations to both FPA and

NAPFA on the potential merits of tactical tilts.

Strategically I have no problem w/your article and your conclusions,

though you are careful w/your word choices opting for “might be”

instead of more Draconian language. It’s the tactical view where I am

getting twisted. Specifically:

1. Your basic thesis is that the “normal” yield

curve is steep. Today the risk of rising interest rates (though it seems

to wane and wax weekly) seems to indicate a flatter yield curve moving forward,

not a steeper one.

2. Your conclusion toward MFs rests on the “not too

big a move” in interest rates. If the historical risk premium in the

10-Year Treasury has been around 2.0% +/- and if inflation is really running

around 2% +/-, would it be illogical to presume that the 10-Yr should be at

something near 4%? And, if one buys that presumption, the change in rates

to get a 2.18% Treasury up to 4.0% would seem to exceed your “big

move” line.

3. You ask why someone would give up a “known”

potential to roll down the yield curve for greater returns against just the

potential that interest rates may, eventually, rise for greater returns….

Wouldn’t this calculus depend on whether someone (adviser or client) would seek

a higher total return out of their fixed income portfolio in exchange for

greater risk?

Thank you so much, in advance, for your thoughts on the

above. If you are ever in the Santa Barbara area, our adviser team would

love the opportunity to take you out on the town and express our gratitude for

all you do.

Steven Weintraub