Executive Summary

Back in 1991, Congress first enabled the "Pease limitation" phasing out itemized deductions, and the "Personal Exemption Phaseout" (PEP), which were designed to limit the tax benefits of those deductions for higher-income taxpayers. While the PEP and Pease limitations were themselves phased out in the mid-2000s, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 re-enacted them beginning in 2013, making them a current tax planning issue.

Yet the irony is that while they are referred to as "phaseouts of itemized deductions" and a "personal exemption phaseout" the reality is that the Pease limitation and PEP are applied primarily based on the extent by which someone’s income is over specified thresholds. As a result, while they're labeled as penalties to deductions and exemptions, the Pease limitation and PEP actually function more like surtaxes on income, amounting to a 1% marginal tax rate increase for the Pease limitation, and another 1% rate increase per family member for the PEP.

The reason why this distinction matters is that ultimately, as surtaxes on income, the PEP and especially the Pease limitation are not actually disincentives against deduction-producing strategies; for instance, with almost all taxpayers, the tax savings of charitable giving is actually identical with or without the Pease limitation! In the end, this means that advisors and their clients should be cautious about trying to avoid deductions when faced with PEP and the Pease limitation; instead, simply recognize their 1% surtax effects, and focus planning on income given the higher marginal tax rates that result!

Understanding PEP And The Pease Limitation And Their AGI Thresholds

Under rules that were (re-)enacted as a part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, higher-income taxpayers face a limitation on the tax benefits they receive for their itemized deductions and personal exemptions.

Specifically, the rules stipulate that under IRC Section 68, for every $1 of income over the specified threshold, 3% of that amount will be subtracted from the taxpayer’s itemized deductions. In addition, under IRC Section 151(d)(3), for every $2,500 of income over the same threshold, the taxpayer will lose 2% of his/her personal exemptions. These two rules, triggering a phaseout of itemized deductions and personal exemptions, are also known respectively as the Pease Limitation on itemized deductions (named after Representative Donald Pease [D-Oh.] who first authored the legislation enacting the rule back in 1991), and the PEP (an acronym for the Personal Exemptions Phaseout).

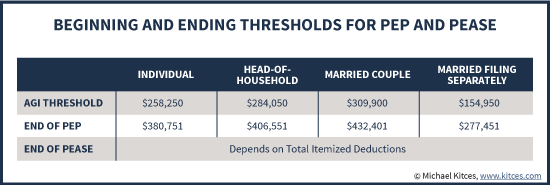

When re-enacted in 2012, the thresholds for PEP and Pease were an Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) of $250,000 for individuals and $300,000 for married couples (and half that amount, or $150,000, for married filing separately); with inflation adjustments, the AGI thresholds for 2015 are $258,250 for individuals and $309,900 for married couples (and again, half the married threshold for couples filing separately).

Notably, because the PEP phases out 2% of personal exemptions for every $2,500 (or fractional amount thereof), its impact eventually ends; after 50 units of $2,500, all 2% x 50 = 100% of the personal exemptions will be phased out. Thus in practice, the PEP begins at $258,250 for individuals but ends after $122,501 of additional income, which equates to an upper threshold of $380,751 (notably, the PEP cap occurs not after 50 x $2,500 = $125,000, but after only $122,501, because the first 98% is phased out after $122,500 and it only takes $1 more to trigger the last fraction-of-$2,500 that results in the last 2% phasing out).

In the case of the Pease limitation, the maximum phaseout is 80% of an individual’s total itemized deductions. Of course, in practice an individual’s itemized deductions themselves tend to rise with income (i.e., higher-income individuals tend to have more itemized deductions for mortgages and charitable giving, as well as more miscellaneous itemized deductions, not to mention that state income tax liabilities also tend to rise with income). As a result, it is rare for the cap on the Pease limitation to be reached. After all, even with no other deductions, a mere 3% state income tax rate is sufficient to increase itemized deductions as quickly as they are being phased out, such that the cap on the Pease limitation would never be reached.

On the other hand, it’s notable that for those subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), the PEP and Pease limitation do not apply, as the AMT already excludes Personal Exemptions (so phasing them out is a moot point), and simply does not apply the Pease limitation (because the AMT already eliminates many itemized deductions anyway). Ultimately, because the PEP and Pease apply under the regular tax system but do not apply under the AMT system, their effective impact is to increase tax liabilities under the regular tax system but not the AMT, which ironically has a net effect of reducing a higher-income taxpayer’s exposure to the AMT (though only because he/she/they are paying more in taxes under the regular system in the first place).

How The Pease Limitation Is Really Just A 1% Surtax On Income

The Pease limitation on itemized deductions is often referred to as a “penalty” against claiming itemized deductions, and a disincentive against deduction-related strategies (e.g., charitable giving). However, a deeper look at how the Pease limitation is calculated reveals that it actually functions not as a penalty to deductions, but as a surtax on income instead. To understand why, it is crucial to recognize how additional income or deductions actually play out at the margin for someone who is subject to the rule.

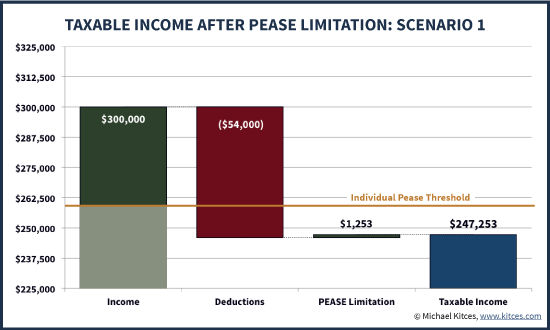

Example. Jerry, an individual taxpayer, has $300,000 of adjusted gross income (AGI), which means he is $41,750 beyond the individual AGI threshold for the Pease limitation in 2015. At $300,000 of income, Jerry is likely to have significant existing deductions. In a state like Pennsylvania (with a flat 3.07% state income tax rate), this would include just over $9,000 in state income taxes, and might also include another $25,000 of mortgage and real estate tax deductions, $10,000 of charitable deductions, and $10,000 of other miscellaneous itemized deductions (e.g., for portfolio management), for a total of $54,000 of deductions. However, because Jerry's $300,000 income is beyond the AGI threshold, his deductions under the Pease limitation are reduced by $41,750 x 3% = $1,253, so his total deductions are only $52,747, and in turn Jerry’s taxable income after deductions would be $247,253 (ignoring Personal Exemptions for a moment), placing Jerry in the middle of the 33% tax bracket.

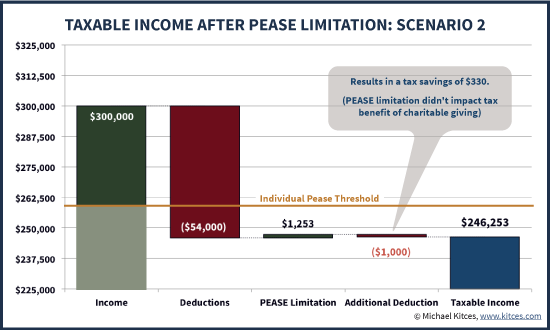

If Jerry were to add another $1,000 of deductions (e.g., by making another charitable contribution), his total deductions would rise by $1,000 (to $53,748), and his taxable income would drop to $246,253. Given this $1,000 reduction in taxable income, and his 33% tax bracket, Jerry would generate $330 of tax savings from the $1,000 deduction. Notably, this means the Pease limitation did not actually impact the tax benefit of his charitable giving, which still generated 33-cents-on-the-dollar in tax savings at his current 33% tax bracket, because the Pease limitation impacts the deductions he already took, not the new deductions at the margin!

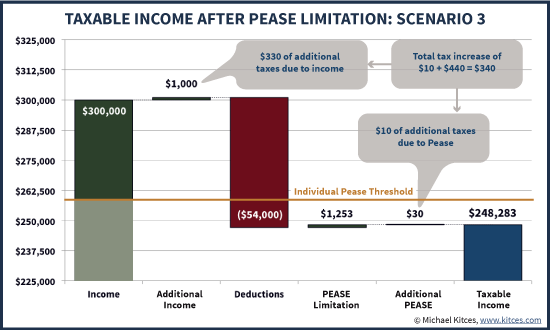

On the other hand, if Jerry were to earn another $1,000 of income, a different result would occur. Jerry’s income would rise to $301,000, which would cause him to be $42,750 over the line, increasing his phaseout of itemized deductions to $1,282.50 (an increase of $1,000 of income x 3% phaseout rate = $30 of additional phaseout). As a result, his deductions would not be $52,747.50, but instead would be $30 lower (at $52,717.50), and accordingly Jerry’s taxable income would be $301,000 - $52,717.50 = $248,282.50. The net result is that Jerry’s total income would be $1,030 higher (another $1,000 of income, plus $30 of lost deductions), which at a 33% tax rate would trigger $340 in taxes.

Consequently, Jerry’s additional income of $1,000 led to a $340 tax increase, which means even though he was in the 33% tax bracket, he actually ended out with a $340 / $1,000 = 34% marginal tax rate. The first 33% is his tax bracket, and the extra 1% is attributable to the $10 of extra taxes triggered by $30 of extra “income” caused by foregone deductions due to the Pease limitation.

In other words, what the above examples show is that once subject to the Pease limitation, additional deductions still benefit at a 33% rate (for someone in the 33% tax bracket), but additional income is subject to a 34% tax rate. Which means that while the Pease limitation is referred to as a phaseout of itemized deductions, in reality its impact is not actually calculated based on deductions, and the Pease limitation did not adversely impact adding more deductions at all. Instead, the Pease limitation functions as a surtax based on generating more income, instead.

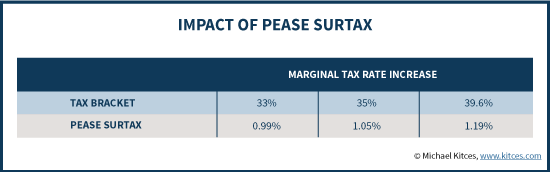

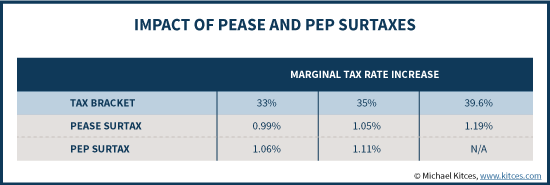

In essence, the Pease limitation causes each dollar of income (above the AGI threshold) to count as more than $1 of income – it counts as $1 of income, plus $0.03 of “extra” taxable income due to the subtraction against itemized deductions. Since that extra $0.03 of income for every dollar will be taxed at a 33% rate (as that’s the tax bracket individuals or married couples will likely be in, by the time the AGI threshold for the Pease limitation is reached), the net result is a $0.01 increase in taxes for every $1 increase in income. This means the Pease limitation is ultimately equivalent to a 1% income surtax (or technically, a 3% [income increase] x 33% [tax bracket] = 0.99% surtax, rounded to 1%).

Notably, though, because the Pease limitation is always adding 3% to income above the threshold, when income rises enough that the tax rate goes up (to 35% and then ultimately the 39.6% tax bracket), the impact of the Pease limitation becomes slightly more severe. Upon reaching the 35% tax bracket, the Pease limitation is equivalent to a 1.05% surtax; at the 39.6% bracket, it is a 1.19% income surtax.

The 1% PEP Surtax… Per Family Member Dependent

As shown above, the Pease limitation might be referred to as a phaseout of itemized deductions, but in reality since it’s calculated based on income (above an AGI threshold), it operates more as a surtax on income. As it turns out, the same is true when it comes to the Personal Exemption Phaseout (PEP) as well.

In the case of the PEP, though, the impact is a bit more nuanced. The Personal Exemption amount is $4,000 in 2015, and the PEP eliminates 2% of this amount for every $2,500 over the threshold. Which means in essence, the PEP reduces the value of the personal exemption deduction by 2% x $4,000 = $80 for every $2,500, amounting to a 3.2% boost in income. In other words, for every $1 of income that someone earns beyond the AGI threshold, their taxable income actually increases by $1.032.

Notably, this means that the marginal impact of the PEP is nearly the same as the Pease limitation! Under the Pease limitation, each $1 of income boosted taxable income by $1.03 (a 3% increase), while the PEP boosts income by $1.032 (a 3.2% increase) beyond the same threshold. And once again, income at that point would be subject to a 33% tax bracket, which means the marginal tax rate impact of PEP is 3.2% x 33% = 1.06%.

As with the Pease limitation, this marginal tax rate impact is higher as the tax bracket itself increases; the PEP results in a surtax of 1.11% in the 35% bracket. On the other hand, the PEP surtax calculation never actually applies to the top tax bracket, because the upper income threshold for the PEP is actually reached before the 39.6% bracket kicks in.

Per Family Member Impact Of PEP On Multiple Personal Exemptions

However, a subtle but important caveat of the PEP is that for couples and families – who have multiple personal exemption amounts (one for each taxpayer/dependent) – the phaseout impacts all the exemptions at once, which effectively means the 1% PEP surtax will apply cumulatively for each/all exemptions.

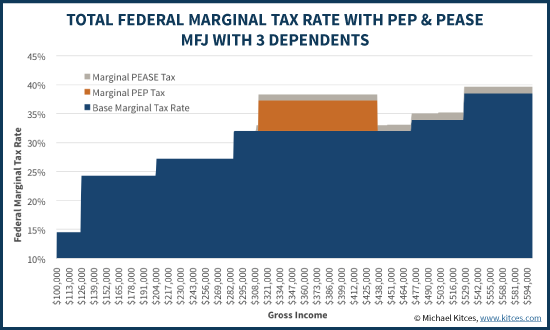

For instance, a married couple with three (young) children is eligible for five personal exemptions, a total of $4,000/exemption x 5 exemptions = $20,000. However, as income rises above the AGI threshold, the couple begins to phase out 2% of all the exemptions at once, which means every $2,500 of income doesn’t just boost income by $80 but by $400 (which is 2% of the total $20,000 of exemptions). Given the 33% tax rate, the net result is whopping $400 / $2,500 x 33% = 5.3% surtax triggered by the PEP, which is the equivalent of five simultaneous 1.06% PEP surtaxes (one for each family member).

Ultimately, then, the key distinction is that while the Pease limitation is a flat 1% surtax for the individual/couple/family, the PEP surtax is approximately 1% per family member – which means it’s actually just 1% for an individual, 2% for a married couple, and over 5% for a family of five! Moreover, this significantly greater impact of the PEP, increasing with family size, continues up until the maximum threshold when the PEP surtax ends because 100% of all personal exemptions have been phased out!

Don't Avoid Deductions - Planning For The 1% Pease And PEP Marginal Rate Surtaxes

Given that the PEP and Pease limitation effectively operate as surtaxes on income that increase the marginal tax rate, planning for/around them occurs the same way any planning should occur based on marginal income tax rates: defer or minimize income when marginal rates are high, and accelerate income if/when marginal rates are low (to avoid higher rates in the future).

In other words, an individual who thinks he/she is in the 33% bracket, but is actually facing a 35.2% rate (thanks to the impact of PEP and Pease), would simply plan accordingly – tax deferral becomes a little more valuable, effective asset location matters a bit more, using an annuity for tax deferral is a little more appealing, and income-acceleration events like Roth conversions become somewhat less appealing. At the simplest level, though, the point is just that planning will really occur the same way it always does, just based on marginal tax rates that are slightly higher once the impact of the PEP and Pease limitation are accounted for.

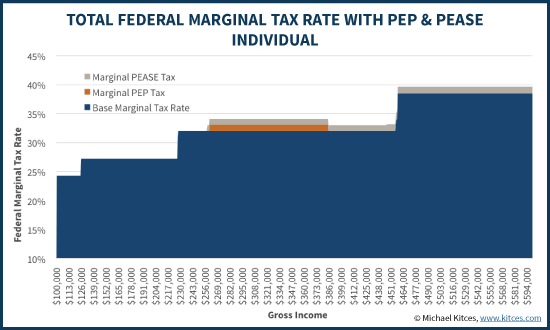

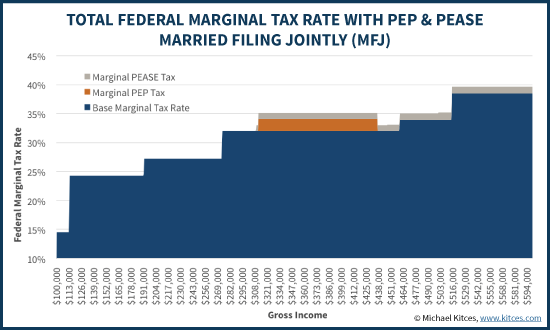

Accordingly, the charts below shows how the PEP and Pease limitation drive the marginal tax rates higher for an individual, a married couple (with no children), and a family of five. In all three cases, once the AGI income threshold is reached, the marginal tax rate increases to recognize not only the rising tax brackets, but the surtaxes for Pease and PEP on top (and the cumulative impact of PEP given multiple family members with simultaneous exemptions phasing out). These examples assume a 3% state income tax rate (and associated state income tax deduction, which slightly reduces the marginal Federal tax rate), along with $5,000 of real estate property taxes, $20,000 of mortgage interest, and $2,000 of charitable contributions. (Michael's Note: These charts show marginal Federal tax rates only; the 3% state income tax rate would add another 3% marginal tax rate on top!)

Notably, many individuals and couples subject to the PEP and Pease Limitation will not actually be impacted by it in the 33% and 35% tax brackets, because in reality they will likely end out being subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) instead (which as noted earlier is not directly affected by PEP and Pease). The AMT applies any time the total tax liability (and thus the effective tax rate) is higher under the AMT system than the regular tax system, and when such situations occur it’s necessary to plan based on the AMT system using its tax brackets and deductions instead, not the regular tax system (and its PEP and Pease rules)!

Ultimately, though, the fundamental point remains that the PEP and Pease simply operate as surtaxes on income, and are not disincentives against charitable giving and other deduction strategies. As shown earlier, a taxpayer who is subject to the Pease limitation phasing out itemized deductions gets the exact same tax savings from charitable giving as would have occurred if the Pease limitation were never created. Notably, the tax benefits of charitable giving are impaired in situations where the 80% cap on the Pease limitation has been reached, but in any other scenario when the Pease limitation remains below the cap, all the normal strategies to maximize tax deductions and savings still apply. Although notably, once the PEP and Pease limitation is in effect, any above-the-line tax deductions become slightly more valuable than below-the-line strategies like charitable giving (because an above-the-line deduction is not only an outright tax deduction, but also reduces exposure to PEP and Pease themselves).

PEP And Pease Vs Just Raising Top Marginal Tax Brackets

Ironically, it probably would have been easier if we simply never (re-)adopted the PEP and Pease rules back in 2012, and simply raised the top three tax brackets by a percentage point or few. Unfortunately, though, changing the top tax brackets was so controversial during the discussions of the “fiscal cliff” tax legislation at the end of 2012 that attempting to do so would have made the legislation impossible to pass. So instead, Congress vowed not to increase rates on high-income taxpayers… and then reinstated the PEP and Pease limitation rules as a part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act to accomplish the same result anyway!

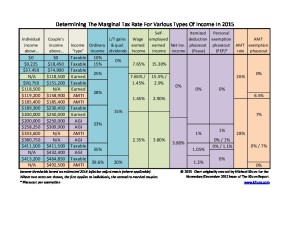

Chart For Determining Marginal Tax Rates In 2015

Until then, however, it is crucial to evaluate all of the rules that can affect marginal tax rates, from the tax brackets themselves, to PEP and Pease, Medicare surtaxes, the Alternative Minimum Tax, and more! To help, you can use the Marginal Tax Rates chart to the right for yourself!

So what do you think? How do you plan for/around the Pease limitation and the PEP? Do you have clients who have avoided charitable giving or other tax deduction strategies due to the Pease limitation? Will you reconsider those strategies going forward? Do you think it would be better if we simply raised the top tax brackets, and eliminated PEP and Pease altogether?

Thanks Michael for the insightful analysis. What impact would Jerry’s additional PA state income tax have on the Pease phaseout? If he would pay $30 additional state income tax on the additional $1000 of income, this would increase his federal deduction by $30, in effect offsetting the pease phaseout and reducing his marginal federal tax bracket back to 33%. Am I thinking about this correctly?

Conner,

Yes, you’re on the right track here.

The reality is that for someone who pays 33% Federal plus 3% state, the reality is that their Federal marginal tax rate isn’t really 33% at that point. It ends out being 32% Federal + 3% state = 35%, because the 3% marginal state tax rate is also producing a 1% reduction in the Federal rate thanks to the state income tax deduction.

So from that perspective, someone who pays 33% Federal plus 3% state is really at a 33% Federal – 1% (state income tax deduction) + 1% (Pease) = 33% Federal. So yes, you do essentially circle back to the same number. (Though obviously a higher or lower state income tax rate will have a slightly different marginal effect.)

– Michael