Executive Summary

Occasionally, an owner of a permanent life insurance policy may decide that they no longer need their policy – either because the death benefit is no longer necessary or because they simply want to access the policy's underlying cash value for their living expenses in retirement. Unlike term life insurance, permanent life insurance doesn't simply lapse when the owner stops paying premiums. Moreover, withdrawing the policy's underlying cash value can trigger significant tax consequences due to the tax-deferred treatment of the funds in the policy.

For example, surrendering or selling a life insurance policy immediately triggers taxation on any underlying gains in the policy's cash value, which can result in a large spike in taxable income. And while policy loans are normally a tax-free option to access cash value, the compounding interest can make them costly over time. Worse, if the loan balance approaches or equals the policy's cash value, the policy may lapse, triggering immediate taxation of the underlying gains (which is especially problematic since most or all of the policy's cash value is then used to pay off the loan, and therefore isn't available to cover the subsequent tax bill).

An alternative strategy is to execute a 1035 exchange, replacing the no-longer-needed life insurance policy for an annuity. In doing so, the policy's cash value and embedded gains carry over from the life insurance policy to the annuity, retaining the funds' tax deferral. Upon annuitizing the contract, payments are taxed as part (tax-free) return of basis and part (taxable) income, spreading out the tax consequences over the entire term of the annuity.

However, exchanging a life insurance policy for an annuity works best when the policyowner plans to annuitize relatively quickly. This is due to non-annuitized withdrawals after the exchange being subject to tax on a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) basis, meaning they're 100% taxable up to the total amount of gain in the contract. To avoid this, policyowners can withdraw funds directly from the life insurance policy prior to initiating the 1035 exchange, where the withdrawal will be taxed on a First-In, First-Out (FIFO) basis and be fully tax-free up to the total amount of basis in the policy. Notably, it's important to remember that any cash received as part of the 1035 exchange – or withdrawals made immediately before the exchange – can be treated by the IRS as "boot" and taxed up to the full amount of the withdrawal. Which makes it essential for a sufficient amount of time to pass between the withdrawal and the 1035 exchange to prevent unintended tax consequences.

The key point is that, as life circumstances change over time, tools like permanent life insurance may no longer meet an individual's needs. And while other strategies like taking a policy loan or simply surrendering the policy might be viable in some circumstances, a 1035 exchange into an annuity can be a more tax-efficient way to access the policy's underlying value when the need for life insurance is replaced by a need for retirement income. Because ultimately, spreading the tax impact of withdrawing the funds over several years usually results in a lower overall tax burden, allowing the owner to keep more of the funds to use as they like!

The point of permanent life insurance is that it's permanent. As long as the owner of the policy pays their required premiums and avoids depleting the policy's cash value with loans and withdrawals, the policy will remain in force until the death of the person whose life it's insuring.

The upside of this feature of permanent life insurance is that it's guaranteed to be around for as long as it's needed. Unlike term insurance, which expires after a set number of years and requires a new round of underwriting to renew once the original term is up (which may cause issues if the insured's health has declined during that time), permanent life insurance has no expiration date and, after the policy is originally issued, never requires further underwriting. In fact, the owner of a permanent life insurance policy can often purchase additional insurance over time in the form of Paid-Up Additions (PUAs) that require no additional underwriting.

The flip side, however, is that if a permanent life insurance policy is no longer needed… it's still there. Because it's permanent. And life circumstances, unlike life insurance policies, are usually not permanent. Which means there may come a time when it makes more sense to unwind a permanent life insurance policy – to free up resources or better align with changing financial priorities – than to leave it in place.

For instance, a parent with young children may have purchased a life insurance policy to provide protection in case they were to die unexpectedly. But once those kids are grown and living independently, there's little reason to maintain the policy (and its death benefit) from a risk management perspective. Similarly, someone might buy a policy to protect their spouse in the event of their death, but if they later get divorced, they may no longer need or want to continue providing that protection for their ex-spouse. Or maybe an individual purchased the policy to accumulate cash value toward their retirement, and now, as their retirement date approaches, they're looking for the most effective way to distribute the policy's cash value to fund their living expenses.

Whatever the reason, because permanent life insurance policies feature both an 'insurance' component (the death benefit paid out to the policy's beneficiary on the death of the insured) and a 'savings' component (the accumulated cash surrender value), the goal is to retain as much of the "savings" portion of the policy as possible while eliminating the unneeded "insurance" portion.

The Tax Consequences Of Surrendering A Life Insurance Policy

If a life insurance policy is no longer needed, it's always possible to unwind the policy all at once by either surrendering the policy for its accumulated cash surrender value or selling it to a third party through a life or viatical settlement. However, these options may be less appealing due to the potential tax consequences, particularly when the policy has significant embedded gains beyond the cumulative premiums paid.

Under IRC Section 72(e), when a life insurance contract is surrendered, a portion of the cash value received is taxable. Specifically, any cash value exceeding the total investment in the policy – defined as the amount of total premiums paid into the policy minus any policy dividends that were paid out in cash or used to reduce premiums – is subject to tax.

Example 1: Andre owns a permanent life insurance policy with a total cash surrender value of $200,000. Over the years, he has paid a total of $100,000 in premiums into the policy, but used $20,000 in policy dividends to reduce his annual premium payments.

As a result, Andre's total investment into the policy is $100,000 (the amount of premiums paid) − $20,000 (the dividends used to reduce premium payments) = $80,000.

If Andre decides to fully surrender the policy, he'll receive the full $200,000 cash surrender value. Of this, $200,000 − $80,000 = $120,000 will be taxed as gain on the policy, while the remaining $80,000 will be tax-free as a return of his investment in the policy.

Notably, the 'gain' portion of the policy – the cash surrender value exceeding the total investment in the policy – is generally taxed at ordinary income rates. This is because the IRS does not treat the surrender of a life insurance policy as the sale of a capital asset.

A policy that is sold to a third party through a life settlement receives similar tax treatment to one that is surrendered directly to the life insurance company: Any embedded gain within the policy is taxed as ordinary income to the extent that the cash surrender value exceeds the total investment in the policy. Additionally, if the policy is sold for more than the cash surrender value (which is often the case since the purchaser typically pays for both the cash surrender value and the present value of the policy's expected death benefit), the amount exceeding the cash surrender value is taxed at capital gains rates. (Though if the policy is sold by a terminally ill person who isn't expected to live for more than 2 years, the sale qualifies as a viatical settlement and is tax-free to the seller.)

The benefit of surrendering or selling the policy in full is that the proceeds are received as a lump sum. After paying any applicable taxes, the remaining proceeds can be spent, invested, or gifted however the owner sees fit. However, surrendering or selling the policy means being taxed all at once on all of the embedded gains within the policy. Which can result in sacrificing a significant amount of the net proceeds to taxes, particularly if the taxable gains are large enough to bump the owner into a higher marginal tax bracket.

As a result, while a surrender or sale might be the simplest way to unwind a life insurance policy that isn't needed anymore, it might not be the most tax-efficient way to access the policy's cash surrender value. For owners who don't need the entire cash value right away, other strategies may preserve more of the policy's value after taxes.

The Risks Of Policy Loans

In addition to selling or surrendering a permanent life insurance policy, another way to access its cash value is through a policy loan. This is effectively a loan made by the insurance company to the policyholder, secured by the policy's cash surrender value. Unlike a surrender, a policy loan doesn't cancel the policy or reduce its cash surrender value, which can keep growing via crediting rates or growth on its underlying investments. Furthermore, policy loan proceeds are tax-free to the borrower, even if the loan exceeds the premiums paid into the policy. This means that a loan, unlike a surrender or sale, allows the policy to retain its tax-deferred treatment. And policy loans typically don't have to be repaid during the borrower's lifetime as long as they don't exceed the policy's cash surrender value; rather, the outstanding loan balance is deducted from the death benefit paid upon the insured's death.

While the tax-favored treatment of policy loans has led to the heavy promotion of strategies like "Bank On Yourself" that use policy loans as a primary funding source for lifestyle expenses in retirement, such approaches also come with major downsides. For one thing, policy loans accrue interest, which compounds over time. If the policyowner doesn't pay at least enough to cover the accrued interest for each period – either from outside funds or from policy dividends – a large portion of the policy's cash value and death benefit can be consumed solely by compounding interest on the policy loan.

An even greater risk is that the loan balance grows to the point where it approaches or equals the policy's underlying cash value. At this point, the policy will lapse, meaning the insurance company will cancel the policy and use the cash surrender value to repay the loan. From a tax standpoint, the IRS considers a policy lapse as equivalent to a full surrender, which triggers the recognition of any embedded gains, even though the gains themselves went towards paying back the policy loan. The result can leave the policyowner with a substantial tax bill but little or no funds remaining from the life insurance policy to pay it.

Example 2: Belle owns a universal life insurance policy with a cash surrender value of $300,000, representing $150,000 of total premiums paid and $150,000 of growth.

20 years ago, Belle took out a policy loan of $100,000. After 2 decades of compounding interest, the loan balance has grown to $300,000, equaling the policy's cash surrender value. This causes the policy to lapse, with 100% of the $300,000 cash surrender value going back to the insurance company to repay the loan.

However, because the IRS considers the policy lapse as a full surrender, Belle will be taxed on the policy's underlying gains of $150,000. Assuming she's in the 24% Federal marginal tax bracket, she'll owe 24% × $150,000 = $36,000 in taxes, despite the fact that she received $0 in net proceeds after the lapse of the insurance policy!

For policyholders who don't want to manage an ever-growing policy loan or monitor it to ensure it doesn't exceed the policy's cash value, a policy loan might not be the best approach. This can be especially tricky with policies like Indexed Universal Life (IUL) policies, where cash value can fluctuate both up and down based on the performance of the underlying investments. And for those who don't want to sacrifice a large portion of their policy's cash value to loan interest, the drawbacks of policy loans may outweigh their benefits.

Partial Surrenders

A third approach to access a life insurance policy's cash value involves partial surrenders or withdrawals from the policy's cash value over time (if the policy allows it), rather than surrendering the policy all at once. Unlike a loan, partial surrenders reduce the policy's cash value over time – and consequently, remove some of the policy's compounding power each time there's a withdrawal. However, this method doesn't accrue interest over time and avoids the risk of a sudden policy lapse.

At first glance, this approach has some appeal on account of how partial withdrawals from life insurance policies are taxed. Because they are taxed on a First-In, First-Out (FIFO) basis, partial withdrawals are treated as coming first from the principal part of the cash value and then from the growth portion. In other words, withdrawals from a life insurance policy are tax-free up to the aggregate amount of premiums paid, since that portion is considered a return of the policyholder's initial investment. Taxes only apply after the policyholder has recovered the full cost of their original premiums.

However, for those who plan to eventually withdraw the entire cash surrender value, there are some downsides. Once they've 'used up' the tax-free portion of their withdrawals, 100% of the remaining withdrawals – all of which represent the growth portion of the cash value – are fully taxable as ordinary income.

Example 3: Curtis has a life insurance policy with a cash surrender value of $1 million, representing $400,000 of total premiums paid and $600,000 of growth. Curtis plans to retire at age 67 and withdraw $100,000 annually from the life insurance policy for the next 10 years to supplement his Social Security and 401(k) plan savings.

For the first 4 years, his $100,000 annual withdrawals will be tax-free since they represent a return of his original premiums. After the first 4 years, however, each $100,000 withdrawal will be fully taxable, as the withdrawals will come from the growth portion of the policy.

Assuming Curtis is in the 24% Federal tax bracket at that time, he'll only get to keep $100,000 − (24% × $100,000) = $76,000 of each remaining withdrawal after taxes. Additionally, the extra taxable income could have compounding effects, like increasing the taxability of his Social Security benefits or triggering IRMAA surcharges on his Medicare Part B premiums, potentially reducing the actual after-tax portion of the withdrawal even further.

In addition to being more difficult for planning purposes (since each withdrawal taken after the original investment is used up will have a lower after-tax value), the FIFO tax treatment of life insurance withdrawals concentrates taxable income into the later withdrawals. Depending on the policyholder's tax situation, this could mean paying a higher tax rate on the policy proceeds than if the tax were spread equally across all withdrawals.

Using A 1035 Exchange Into An Annuity To Spread The Tax Impact Of Life Insurance Withdrawals

One more option for a life insurance policy that's no longer needed is to exchange it for an annuity via a 1035 exchange. Under IRC Section 1035, life insurance policies can be exchanged "in-kind" for another life insurance policy, an annuity, or a long-term care insurance policy with no taxable gain or loss recognized on the exchange, as long as the old and new policies have equivalent cash values. Which effectively allows the policyowner to use the accumulated cash value from a life insurance policy to purchase an annuity while retaining the tax-deferred treatment of any gains within the policy.

Taxation Of Annuity Distributions After A 1035 Exchange

In a 1035 exchange, the original investment in the life insurance policy (i.e., the premiums paid, minus any partial surrenders or cash dividends received) carries over as the cost basis of the annuity contract. This cost basis determines the tax treatment of any subsequent withdrawals or annuity payments from the annuity.

Once the 1035 exchange is completed, the owner essentially has 3 options:

- Keep the annuity in place and let its underlying value continue to grow tax deferred;

- Take withdrawals without annuitizing the contract; or

- Annuitize the contract and begin receiving regular payments.

Keeping the annuity in place generally makes the most sense if there's no immediate need for any payments from the annuity. However, in most cases, the 1035 exchange itself implies a need to access the cash in the annuity; otherwise, keeping the funds in the original life insurance policy would have effectively accomplished the same tax-deferred growth without the added complexity of the exchange. As a result, it's uncommon for a policyholder to go through the process of a 1035 exchange into an annuity without eventually taking any distributions.

Likewise, taking immediate withdrawals from the annuity is often less favorable due to the way annuitized annuity withdrawals are taxed. Unlike life insurance policies, where withdrawals are taxed on a First-In, First-Out (FIFO) basis, withdrawals from a non-annuitized annuity are taxed on a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) basis. This means distributions are 100% taxable as ordinary income to the extent of any gain, with the tax-free return of the original investment representing the last dollars withdrawn. Additionally, any withdrawals within the first 7–10 years of the annuity are likely to come with surrender charges, plus all withdrawals taken before age 59 1/2 are subject to an additional 10% early distribution tax (unless they qualify for an exception under IRC Sec. 72(t)). All of which means that making a 1035 exchange into an annuity with the intent of taking withdrawals from the cash value isn't likely to be a viable strategy.

The Exclusion Ratio Treatment Of Annuitized Payments

The third (and typically the best) option after a 1035 exchange into an annuity is to annuitize the contract. Unlike non-annuitized withdrawals (which are subject to LIFO tax treatment), annuity payments are only partially taxable. Each payment is divided into 2 parts: a tax-free return of the investment (basis), and taxable income representing the gain in the annuity.

The tax-free portion is determined by the "exclusion ratio", which is calculated by dividing the total investment in the contract (i.e., the basis carried over from the original life insurance policy) by the total number of expected annuity payments. These expected payments are based on the age and actuarial life expectancy of the annuitant, as provided in IRS Pub. 939.

Example 4: Esther is a 70-year-old retiree who has an annuity with a cash value of $250,000, representing an original investment of $150,000 and gains of $100,000.

If she annuitizes the contract today, the annuity will pay her monthly payments of $1,600 for the rest of her lifetime. According to IRS Pub. 939, her actuarial life expectancy is 15 years.

Using the exclusion ratio calculation above, the tax-free portion of each payment will be $150,000 (her total investment in the contract) ÷ (15 × 12 = 180) (the number of total expected annuity payments) = $833.33. The remaining $766.67 of each payment is treated as taxable gain.

The exclusion ratio treatment of annuity payments spreads the tax impact of payments from an annuity across the annuitant's lifetime, unlike the taxation of life insurance distributions and non-annuitized annuity withdrawals. Recall that life insurance distributions are taxed on a FIFO basis, allowing tax-free withdrawals until the original basis is exhausted, after which withdrawals become fully taxable; while non-annuitized annuity withdrawals are taxed on a LIFO basis, where taxable gains are distributed first, followed by tax-free distributions of the remaining basis.

Dividing the tax burden across all annuitized payments can often mean a lower overall tax rate on lifetime withdrawals than if the tax impact were concentrated into just the first few or the last few years of payments. Furthermore, once an annuity has been annuitized, there are generally no surrender charges or early distribution taxes on payments from the annuity.

In sum, the best use cases for 1035 exchanges of life insurance policies for annuities are when:

- There's no longer any need for the life insurance policy and its death benefit; and

- The owner wants to immediately (or at least within a few years) annuitize and begin receiving lifetime payments

This strategy is particularly useful for people whose circumstances have changed – such as those who have divorced, whose children have grown and are no longer dependent on their income, who have leftover life insurance policies from a cross-purchase agreement for a business that has since been dissolved, or whose need for a lump-sum life insurance benefit for their beneficiaries has been subsumed by a need for a steady lifetime income. For these individuals, a 1035 exchange into an annuity, followed by annuitization once the income is needed, offers a tax-efficient way to access the life insurance policy's cash value, particularly if there are significant embedded gains.

How To (Correctly) Execute A 1035 Exchange Into An Annuity

Full Vs Partial 1035 Exchanges

After deciding to exchange a life insurance policy for an annuity via a 1035 exchange, the next step is to determine whether the entire policy is to be exchanged and used to fund future annuity payments, or if there's a need for any funds that should remain outside the annuity. The timing of withdrawals can have a big impact on how they're treated for tax purposes.

As noted above, withdrawals from a life insurance policy are taxed on a First-In, First-Out (FIFO) basis. By contrast, pre-annuitization withdrawals from an annuity are taxed on a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) basis, while also potentially being subject to surrender charges and/or the early distribution tax if the owner is under age 59 1/2.

Which means that if there is an immediate need for funds beyond the steady lifetime annuity payments post-1035 exchange, it's generally better to withdraw those amounts from the policy before executing the 1035 exchange. That way, the withdrawal would be subject to the more favorable FIFO treatment of life insurance withdrawals rather than the LIFO treatment for annuity withdrawals.

Example 5: Demetrius owns a cash value life insurance policy to which he's paid $150,000 in premiums over the years. Over time, the policy's cash value has grown to $250,000, and there have been no previous loans or distributions from the policy.

Demetrius's original investment in the policy equals the $150,000 of premiums paid, while the additional $100,000 of cash value represents the embedded gain in the policy.

Demetrius decides to do a 1035 exchange of the life insurance policy for an annuity, but he would also like to withdraw $50,000 to pay for home improvements.

If he withdraws the $50,000 from his insurance policy before the 1035 exchange, the withdrawal would come first from his original investment in the policy – and since his original investment is $150,000, the entire withdrawal would be treated as a tax-free return of basis.

On the other hand, if he waits until after the exchange to withdraw the funds from the annuity, the distribution would be treated as coming first from gains – meaning that the entire $50,000 would be taxable as ordinary income (in addition to being subject to any surrender charges imposed by the annuity provider, plus a 10% early distribution tax if he's under 59 1/2).

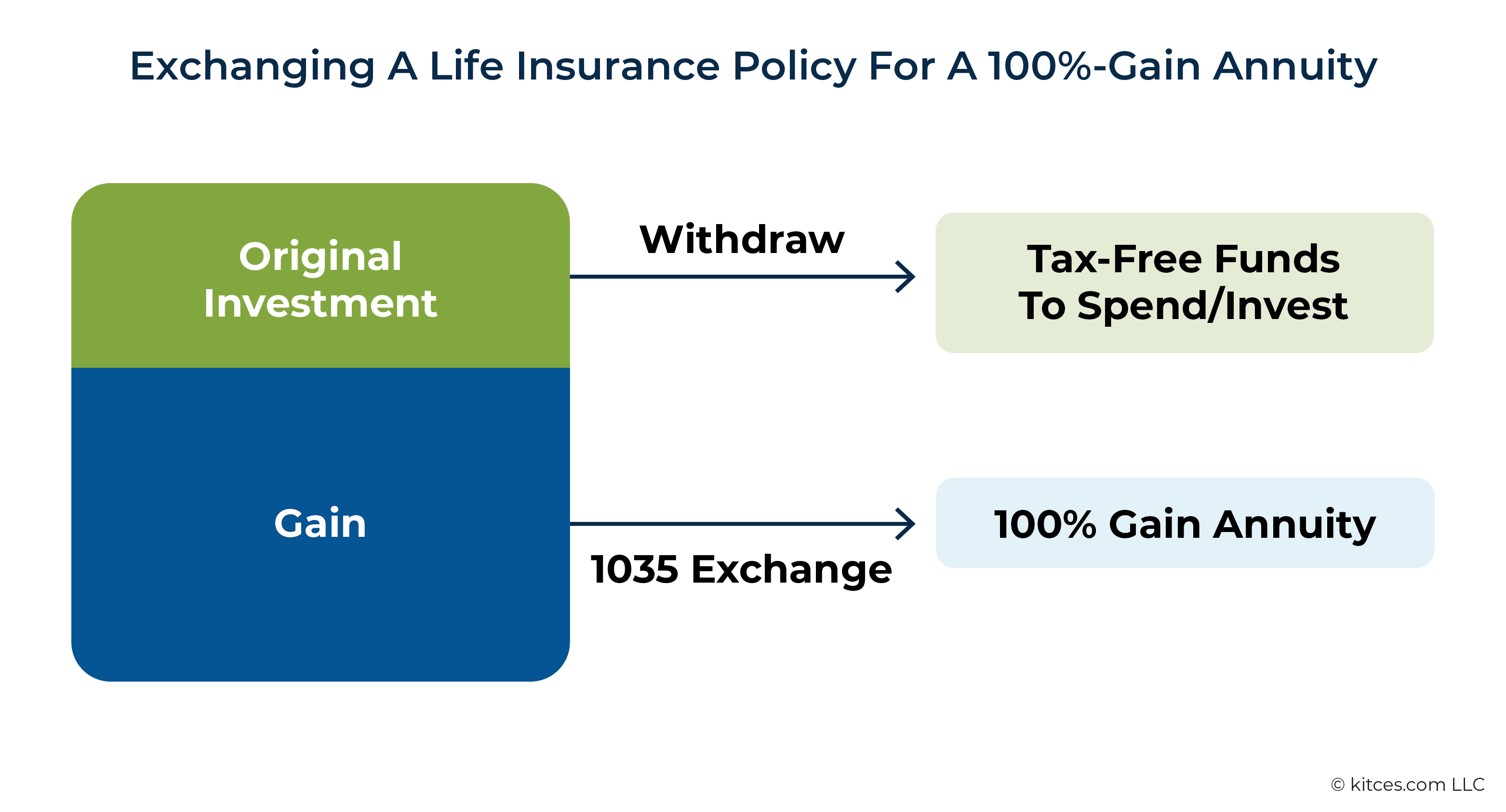

Deferring Just The Gain Portion With A 100%-Gain Annuity

At the extreme, a life insurance policyowner could withdraw up to their entire original investment in the policy tax-free, then exchange only the 'gain' portion of the policy for an annuity. Which would allow them to free up the tax-free portion of the cash value to use or invest however they want, while preserving the tax deferral of the gains portion of the cash value.

The caveat, however, is that this would effectively reduce the 'original investment' portion of the annuity's cash value to zero – meaning that, after the 1035 exchange, all future withdrawals from the annuity (including annuity payments over the owner's lifetime) would be 100% taxable, since there would effectively be no remaining basis that would have made a portion of each payment tax-free. However, the taxable dollar amount of each payment will remain the same either way, since the taxable 'gain' portion of the contract remains the same regardless of how much of the original investment is left.

From a planning perspective, this sort of 100%-gain annuity takes what is technically a nonqualified annuity – funded with after-tax dollars and benefiting from the partially taxed exclusion ratio treatment for its annuity payments – and makes it more akin to a qualified annuity, whose underlying cash value is 100% pre-tax and whose payments are generally 100% taxable.

However, unlike a qualified annuity, a 100%-gain nonqualified annuity doesn't have any RMD rules. And if the annuity owner dies before annuitizing the contract, their beneficiaries can stretch distributions from the annuity over their lifetime rather than being required to fully distribute the annuity within 10 years (as is the case with qualified annuities inherited by non-spouse beneficiaries).

Avoiding "Boot" And Taxation Of Withdrawals Before 1035 Exchanges

However, there's an important consideration when withdrawing funds alongside a 1035 exchange. Under IRC Sec. 1031(b), if any property received from a 1035 exchange is not "solely in kind" – for example, if the insurance policy is not solely exchanged for an annuity, but for some combination of the annuity and other assets like cash – then the additional assets are recognized as gain on the exchange and become 100% taxable. The taxable amount is the lesser of the amount of cash received or the amount of embedded gain in the policy.

In other words, similar to 1031 exchanges where any non-like-kind property (referred to as "boot") received as part of the exchange loses its tax-deferred treatment and becomes taxable, any cash received in the course of a 1035 exchange also becomes immediately taxable.

Which is to say that any withdrawal of the original investment from the life insurance policy should not be done as a part of the 1035 exchange itself. Doing so would turn what would have been a tax-free return of basis into a fully taxable receipt of non-like-kind property.

Additionally, any withdrawals made immediately before the exchange could be treated by the IRS (via the "step transaction" doctrine) as part of the exchange, and likewise treated as boot. There's no specific guideline for how much time needs to pass between the withdrawal and the 1035 exchange to ensure that they're treated as separate transactions – it depends on whether the IRS determines the separation was solely intended to avoid having the non-like-kind proceeds taxed as boot.

To minimize potential issues, it may be best to schedule the withdrawal and the exchange in separate tax years and to have some specific immediate purpose for the funds withdrawn. These steps may make it easier to show that the withdrawal was made for its own purposes, separate from the 1035 exchange, and not done solely to avoid the tax consequences of receiving non-like-kind proceeds.

Treatment Of Outstanding Policy Loans

In addition to cash withdrawals prior to a 1035 exchange, the boot rules can also come into play when the exchange involves a life insurance policy with an outstanding policy loan. If a loan is extinguished (i.e., paid off with a portion of the policy's underlying cash value) as a part of the 1035 exchange, the amount paid off is also considered boot and is taxable to the extent of the underlying gain in the policy.

To avoid this outcome, a life insurance policyowner with an outstanding policy loan who wants to do a 1035 exchange for an annuity could pay off the loan using their own funds from outside the policy. This repayment could be made at any time before the 1035 exchange since it doesn't involve withdrawing funds from the policy.

Example 6: Dinah owns an insurance policy with a $100,000 cash value and a $20,000 loan balance, resulting in a net cash value of $80,000. Her cost basis in the policy is $60,000, with $40,000 of embedded gains.

If Dinah pays off the $20,000 loan balance with funds from her checking account, she can then immediately 1035 exchange the policy for an annuity, with no taxable gain recognized on the transaction.

Otherwise, they could pay the loan using funds from inside the policy, which would again need to be done a reasonable amount of time prior to the 1035 exchange to avoid the IRS applying the step doctrine and treating it as part of the exchange.

Example 7: Dinah, from the previous example, decides to use the policy's cash value to pay off her policy's loan balance before the 1035 exchange instead of paying with outside funds.

If she does so as a part of, or immediately before, the 1035 exchange, the amount used to pay off the loan will be considered boot in the exchange. This means that the amount is taxable up to the lesser of the cash received or the policy's total gain.

Since the amount of cash value used to pay off the loan is $20,000, and the total gain on the policy is $40,000, Dinah will be taxed on the $20,000.

However, if Dinah pays off the loan using the policy's cash value well in advance of the exchange, the repayment is treated as any other withdrawal from the policy and taxed on a FIFO basis. Since Dinah's cost basis in the policy is $60,000, the entire $20,000 used to pay off the policy loan would be considered a tax-free return of basis.

Additionally, policyowners may have the option to carry over the loan balance into the annuity, though not all annuity carriers may permit this. As a result, the selection of annuities available for the exchange may be limited. In practice, the best approaches for policyowners are to either 1) pay off the policy loan using funds from outside the policy any time before the 1035 exchange; or 2) pay off the loan using funds from the policy's cash value, ensuring it is done far enough in advance of the exchange to avoid the repayment being treated as the receipt of non-like-kind property.

The key point is that both life insurance and annuities are best thought of as tools to achieve specific goals – a death benefit for the protection of beneficiaries in the case of life insurance, and a series of guaranteed payments in the case of annuities, with tax deferral and some access to the underlying cash value in both products. And when an individual's life circumstances and goals change, the best tool for accomplishing those goals may change as well.

For a life insurance policy owner who no longer needs the policy's death benefit, it's worth exploring all the options available, from policy loans and withdrawals to surrendering the policy or selling it in a life or viatical settlement to a 1035 exchange into a long-term care policy or annuity. Depending on the policyowner's new circumstances, some of those options might make more sense, and some might make less sense.

But for an individual for whom the pendulum has swung from a need for life insurance to a need for retirement income, and who doesn't want to incur the tax consequences of surrendering or selling the policy all at once, a 1035 exchange – either for the full value of the life insurance policy, or for just the "gain" portion after withdrawing up to the basis in the policy – can be the most tax-efficient way to spread out the tax impact of accessing the policy's cash value.

Leave a Reply