Executive Summary

One of the most significant changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was the creation of new IRC Section 199A, which provides small business owners with an up-to-20% deduction on the profits of their business. High income business owners have a number of complicated restrictions and/or “tests” that can reduce or eliminate that deduction, but for taxpayers with income below the start of their applicable phaseout range ($160,700 for single filers / $321,400 for joint filers) the deduction calculation is far more straightforward. Taxpayers “simply” receive a deduction equal to 20% of their (combined) qualified business income. Or, if lower, simply 20% of their taxable income (less capital gains and qualified dividends).

Notably, this potentially-lower 20%-of-taxable-income limit on the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction means that small business owners need to have some level of non-QBI income, to absorb the various tax deductions (e.g., the standard deduction or itemized deductions) they claim on their personal return, or they may not get the “full” QBI deduction on their business income. And while some business owners do have substantial amounts of non-qualified-business-ordinary-income, enabling them to receive the 20% deduction on the full amount of their Qualified Business Income, other business owners’ incomes are completely (or, at least, substantially) comprised of only Qualified Business Income. In such situations, the business owner’s deductions effectively get applied against their Qualified Business Income, reducing their QBI deduction (to “just” 20% of taxable income after those deductions).

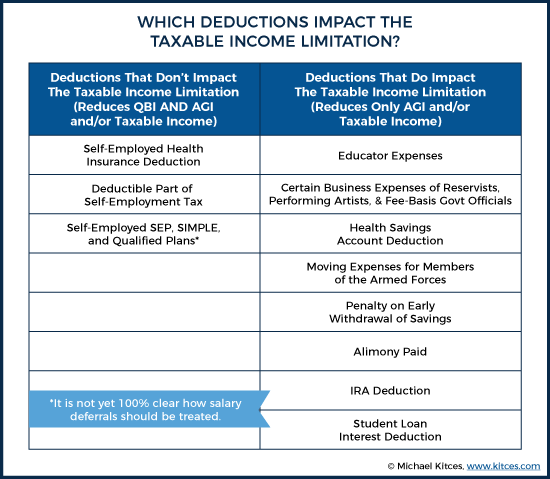

However, not all deductions claimed on the personal tax return create this QBI deduction “problem” for small business owners. Some above-the-line deductions, such as the deduction for SE tax, SEP IRA contribution, and self-employed health insurance reduce both qualified business income and taxable income. Other above-the-line deductions, such as the deductions for IRA contributions, HSA contributions, and student loan interest, along will below-the-line deductions (either itemized deductions or the standard deduction) reduce only taxable income, potential limiting what could be a higher QBI deduction to 20% of taxable income.

Thankfully, though, this complication also presents taxpayers with a significant tax planning opportunity. By accelerating income, a portion of the tax liability that would normally be attributable to the increased income can be covered by a corresponding increase in the taxpayer’s 199A QBI deduction. And ultimately, this can lead to the “Deduction-Production” income being taxed at “just” 80% of the otherwise-applicable tax rate. And this Deduction-Production income strategy can continue to produce favorable results until a taxpayer’s total ordinary income, which is not qualified business income, equals the total of their deductions that reduce taxable income, but not qualified business income.

Of all of the ways in which a taxpayer can accelerate their income and engage in 199A QBI Deduction-Production, the “best” way will most likely be via Roth conversions. Not only do such conversions allow the business owner to reap the benefits of the “discounted” (via Deduction-Production) effective tax rate today, but they also help manage future taxes via continued tax-deferral and future tax-free distributions from the Roth account. Roth conversions are also easy to initiate and allow the business owner to precisely control the amount of income generated.

For those business owners who would benefit from Deduction-Production income, but who cannot make Roth IRA conversions, other options include earning additional W-2 wages, transitioning qualified dividend-producing investments to investments that generate ordinary income, taking distributions from non-qualified annuities, and simply timing deductions so that they occur in other years.

Of course, generating Deduction-Production income only works when the addition of more taxable income would increase the business owner’s 199A deduction. For high-income (taxable income of more than $160,700 for single filers, and more than $321,400 for joint filers for 2019) owners of specified service trade or businesses (SSTBs), additional income may reduce the current QBI deduction further, even if it’s currently constrained by the taxable income limitation, making Deduction-Production income a moot point. The same issue may also present itself to high-income owners of non-SSTBs if their QBI deduction is impacted by the wage or wage-and-depreciable-property tests.

In the end, though, the important thing to remember is that tax planning is first and foremost about trying to pay taxes at the lowest possible rate… something that is a lot easier to do when 20% of your income is effectively tax-free thanks to a deduction that increases in tandem with your income. Thus, for business owners who have their QBI deductions restricted by the taxable income limitation, accelerating “Deduction Production” income must be given adequate and careful consideration.

In December of 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, dramatically altering the tax planning landscape for years to come. One of the most significant changes made by the law was the creation of the new Internal Revenue Code Section 199A for “Qualified Business Income."

While the calculation of the 199A QBI deduction can, at times, become rather complicated, for most taxpayers (whose incomes in 2019 won’t reach the applicable phaseout range for the QBI deduction beginning at $160,700 for single filers and $321,400 for married couples filing a joint return), the “basic” 199A formula can be used to calculate their QBI deduction.

Simply put, such taxpayers are eligible to receive Qualified Business Income tax deduction equal to 20% times the lesser of:

- Their (combined) qualified business income, or;

- Their taxable income (before applying the 199A deduction itself).

“Combined qualified business income” is equal to the net profits of all of a taxpayer’s businesses, plus net profits from REIT dividends and publicly traded partnerships. For those who aren’t investing in REITs or publicly traded partnerships, then, “combined qualified business income” simply comes down to, “What was the qualified business income generated by the business itself?”

In many cases, though, business owners have more total income than just their (combined) qualified business income (e.g., also including other investment income, a spouse’s W-2 wages, etc.). As a result, even after deductions are considered, their total taxable income is greater than their qualified business income. Which simply means the QBI deduction itself is limited to 20% of their qualified business income in the first place (since that would be less than 20% of their total taxable income, even after all other deductions).

However, if a business owner’s total personal income is entirely (or even just mostly) comprised of qualified business income from the business, then their various personal and other deductions will end out applying directly against their business income (on their personal tax return), such that 20% of their taxable income is less than 20% of their qualified business income. In other words, when a business owner’s income is “too concentrated” in the business alone, they may not be able to receive the otherwise-maximum QBI deduction that might have been available based on their business income alone.

Example #1: Sally is a single, sole-proprietor-CPA who has $100,000 of net profit on her 2019 Schedule C. After subtracting $7,065 from Sally’s Schedule C net profit to account for the deduction for one-half of her self-employment tax (as required by the 199A Final Regulations issued by the IRS on January 18, 2019), Sally’s qualified business income for 2019 is $92,935. Thus, the maximum potential QBI deduction that Sally could receive for the qualified business income generated by her CPA practice is $92,935 x 20% = $18,587.

Suppose though, that Sally’s business income is her only income for the 2019 tax year, and that she claims the minimum amount of additional deductions… the $12,200 standard deduction for a single filer in 2019. Based on these facts, Sally’s 2019 taxable income, prior to the application of the 199A deduction, will be $80,735. Which would produce a QBI deduction of only $80,735 x 20% = $16,147.

Since the QBI deduction is ultimately limited to the lesser of 20% of Qualified Business Income ($18,587 for Sally) or 20% of taxable income ($16,147 for Sally), the final QBI deduction for Sally will be only $16,147.

As the example above illustrates, even though Sally would normally get a QBI deduction of $18,587 (based on 20% of her qualified business income), because Sally’s only income is from the business, and her personal deductions (in this case, the standard deduction) effectively applied against her business income on her personal tax return, Sally “only” gets a QBI deduction of $16,147 instead.

Thus, her potential QBI deduction is reduced by $18,587 potential deduction - $16,147 actual deduction = $2,440 as a result of the taxable income limitation.

Determining When The QBI Deduction Will Be Limited By Taxable Income

As can clearly be seen in the example above, if a taxpayer’s only source of income is qualified business income (i.e., only net profits from a sole proprietorship on Schedule C or net profits from a partnership as reported in Box 1 of Schedule K-1), taxable income will always be less than qualified business income. Because if the individual’s sole income is the business income, and any level of personal-return deductions are applied against it – generally, at least the standard deduction, or if greater their itemized deductions – then taxable income will simply be the business income reduced by personal deductions, which is always lower than the business income itself. And accordingly, this will limit the QBI deduction.

Thus, in order to avoid the 199A taxable-income-limitation, a taxpayer must effectively have other income, equal to or greater than their below-the-line deductions (the greater of their applicable standard deduction or itemized deductions), such that even after deductions, their taxable income is still at least as much as their original qualified business income.

However, the caveat is that not just any type of income will be eligible to lift taxable income for purposes of the QBI deduction.

“Taxable Income” Doesn’t Include Capital Gains Or Qualified Dividends

One important caveat for those subject to the 199A deduction taxable income limitation is that not all taxable income actually counts as “taxable income” for 199A deduction purposes.

Specifically, IRC Section 199A(a)(2) states that (for purposes of the 199A deduction) the term “taxable income” does not include “the net capital gain (as defined in section 1(h)).” And IRC Section 1(h)(11(A) states:

“In general

For purposes of this subsection, the term “net capital gain” means net capital gain (determined without regard to this paragraph) increased by qualified dividend income.”

Thus, for purposes of the 199A taxable income limitation, taxable income really means “taxable income, minus net capital gains (regardless of whether those gains are long-term or short-term), minus qualified dividends (but not ordinary dividends).

Not All Deductions Impact The QBI Taxable Income Limitation Equally

Of course, below-the-line deductions are not the only ways that taxpayers can reduce their taxable income. Rather, in addition to their standard deduction/itemized deductions, many taxpayers also claim one or more above-the-line deductions on their personal tax return, which also reduce taxable income (and also adjusted gross income). Thus, unfortunately, determining whether above-the-line deductions will have the same QBI deduction taxable-income-limiting impact for a business owner is more complicated.

Notably, while it might seem odd that deductions taken on a personal income tax return could reduce qualified business income, the Final 199A Regulations released by the IRS on January 18, 2019 make this oddity explicitly clear. Specifically, Treasury Regulation Section 1.99A-3(b)(vi) reads, in part:

For purposes of section 199A only, deductions such as the deductible portion of the tax on self-employment income under section 164(f), the self-employed health insurance deduction under section 162(l), and the deduction for contributions to qualified retirement plans under section 404, are considered attributable to a trade or business to the extent that the individual’s gross income from the trade or business is taken into account in calculating the allowable deduction, on a proportionate basis to the gross income received from the trade or business.

In other words, some above-the-line deductions will reduce both taxable income and qualified business income, which also indirectly means some above-the-line deductions reduce taxable income but not qualified business income. As a result, not all deductions on the personal return are necessarily problematic, as only the latter exacerbates the impact of the taxable income limitation on the QBI deduction (because they increase the difference between QBI and taxable income), whereas deductions of the former do not have the effect because they also reduce QBI itself by an equivalent amount!

Example #2a: Recall Sally from Example #1, who is a single sole-proprietor-CPA with $100,000 of net profit on her 2019 Schedule C. Further recall that after accounting for Sally’s $7,065 deduction for self-employment taxes, her qualified business income was $92,935, and after accounting for both her $7,065 (above-the-line) deduction for self-employment taxes and $12,200 standard deduction, Sally’s taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) was $80,735. Thus, her maximum potential QBI deduction was limited to $16,147 (20% of her taxable income) instead of $18,587 (20% of her qualified business income), effectively reducing her QBI deduction by 20% of the amount by which her taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) was less than her QBI, or ($92,935 - $80,735) x 20% = $2,440.

Suppose, however, that Sally decides to make a $10,000 SEP IRA contribution (which actually may not be the best approach given its potential to result in a 199A Deduction-Reduction). Per Treasury Regulation Section 1.99A-3(b)(vi), as explained earlier, Sally must reduce her QBI by $10,000. Thus, as a result of the contribution, her QBI drops to $82,935, reducing her maximum potential QBI deduction to $16,587.

At the same time, however, the $10,000 SEP contribution will also reduce Sally’s taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) by $10,000, to $70,735. This, in turn, reduces her actual QBI deduction to $14,147. Not coincidentally, the difference between this amount, and Sally’s potential QBI deduction (after her SEP contribution) is $2,440, exactly the same amount by which her QBI deduction was reduced due to the 199A taxable income limitation before the SEP IRA contribution.

As the above example highlights, while the SEP IRA contribution reduced the value of Sally’s SEP IRA contribution (due to the QBI Deduction-Reduction), it at least did not amplify the adverse impact of the 199A taxable income limitation. Because SEP IRA contributions reduce both the business’ income itself and taxable income at the same time.

Example #2b: Continuing the prior example, let’s imagine that Sally also makes a $2,000 contribution to an HSA for 2019, and thus, is entitled to a $2,000 above-the-line deduction for her contribution. This $2,000 deduction does not further reduce QBI, but it would reduce her taxable income by another $2,000.

Thus, Sally’s maximum potential QBI deduction would continue to be $82,935 x 20% = $16,587, but as a result of the taxable income limitation, her actual QBI deduction would now be reduced to ($70,735 - $2,000 = $68,735) x 20% = $13,747.

The end result of Example 2b, above, is that Sally’s actual QBI deduction is now $2,840 less than her maximum potential QBI deduction (as compared to $2,440 in the prior Example 2a). Thus, there is a $400 increase in the amount of lost QBI deduction due to the taxable income limitation, as a result of Sally’s non-QBI-reducing deduction for her HSA contribution. Or viewed another way, the HSA deduction was less valuable than it would have been, because the HSA deduction itself effectively reduced the QBI deduction, given that Sally was already subject to the taxable income limitation.

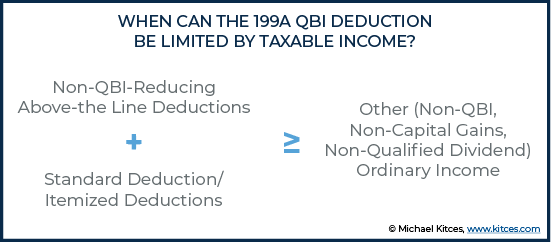

Putting it all together, if a taxpayer’s taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) is below their applicable phaseout range, then the taxpayer’s QBI deduction will be reduced by the taxable limitation when the following formula is true:

Or stated differently, IF non-QBI-reducing above-the-line deductions + the standard deduction/itemized deductions ≥ other (non-QBI) ordinary income, then the QBI deduction will be limited to 20% of taxable income.

This difference between the way the QBI-reducing deductions and non-QBI-reducing deductions impact the ultimate QBI deduction calculation is a critical concept to understand in order to maximize 199A deduction planning, specifically in scenarios where the taxable income limitation has come into play. Notably, though, the impact that QBI-reducing deductions have on the ultimate QBI deduction calculation cannot be offset by other planning, as they reduce QBI itself. By contrast, the impact that other, non-QBI-reducing deductions have on the QBI deduction calculation can be offset… by having – or generating – more taxable income!

Increasing Income Can Increase The QBI Deduction Under The Taxable Income Limitation

When a person’s QBI deduction is limited by their taxable income (e.g., as opposed to their QBI, or due to wage/depreciable property phaseouts), their QBI deduction can be increased – up to a point – by adding more taxable income (that isn’t a capital gain or qualified dividend). While this does increase the overall tax bill, a portion of the tax attributable to the increase in income is offset an increase in the QBI deduction. Which means, in essence, it is unusually-low-taxed income!

Example #3: Al and Peggy are married and file a joint return. Al is a partner in Harry’s Shoes and Accessories, a very successful local shoe store. In 2019, Al’s share of net profits from the partnership are expected to be $275,000. This will be the couple’s only income for the year.

As such, after accounting for the couple’s $11,923 deduction for self-employment tax, their QBI will equal $263,077. However, suppose that in addition to the deduction for self-employment taxes, the couple also has $45,000 of itemized deductions (e.g., from a substantial mortgage on the recent new home they purchased for their family). As such, their taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) is $218,077, and since this amount is less than the couple’s $263,077 QBI, their 20% 199A deduction will equal to (i.e., limited to) $218,077 x 20% = $43,615.

After accounting for the QBI deduction, Al and Peggy have taxable income of $218,077 - $43,615 = $174,462, which gives them a Federal income tax liability (excluding self-employment taxes) of $23,881, and puts them squarely in the 24% bracket for 2019. Given this reality, one would expect that if Al and Peggy were to add additional income to their return, they would pay tax at a 24% rate… but that’s not necessarily what happens.

For instance, suppose that Peggy decides that now that the couple’s children are a bit older and in school, she wants to go back to work part time. If Peggy were to earn a $30,000 salary (W-2 wages) for her part-time work, it would be logical to expect that the couple’s federal income tax bill would increase by $30,000 x 24% = $7,200. But run the numbers and you’ll find that when you add the $30,000 salary, the couple’s taxable income increases by “just” $24,000, resulting in an increase in Federal income tax of “just” $5,760!

But how can this be!?

In short, Peggy’s $30,000 of W-2 wages are partially offset by the production of more 199A deduction. More specifically, the additional $30,000 of wages increases the couple’s taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) to $248,077. This amount is still less than the couple’s QBI of $263,077, but is much closer than before, and results in an actual QBI deduction of $49,615. That’s $6,000 more than the couple’s QBI deduction would have been before Peggy went back to work and earned more income!

The increase in the QBI deduction is the reason why adding $30,000 of actual income only increases final taxable income by $24,000. And by the same token, it’s also why the couple’s tax rate on the actual $30,000 was “only” a very favorable 19.2% and not 24%. In other words, the QBI Deduction-Production process effectively created a tax rate equal to 80% of the original bracket rate (24% x 80% = 19.2%). Or viewed another way, Peggy’s didn’t have to pay taxes on 20% of her new employment income, because her salary increased the household’s taxable income limitation enough to produce an extra $6,000 of QBI deductions on Al’s shoe store business profits!

Limits On QBI Deduction-Production Income

The end result of the above example is that, in situations where the QBI deduction is being limited by taxable income in the first place, producing more income can actually increase the QBI deduction (by 20% of that additional income), and in the process such Deduction-Production Income is taxed at only 80% of the otherwise applicable rate.

A “real” Federal income tax rate that is just 80% of the stated Federal income tax rate probably sounds rather appealing. But it’s important to remember that the QBI Deduction-Production Income process is not one that continues forever. Rather, once taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) equals QBI, the Deduction-Production effect stops, and additional income will not result in an increased QBI deduction. Thus, such income will simply be taxable again at the “retail rate” of a taxpayer’s applicable tax bracket(s) (or ultimately, the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate after considering the potential phaseout of key deductions and/or credits).

Example #4: Recall Al and Peggy from Example #3. When we last “left them,” in addition to Al’s $275,000 of partnership profits from the shoe store, Peggy was working part-time and earning a $30,000 salary. After taking into consideration the couple’s $45,000 of itemized deductions, they were left with QBI of $263,077, taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) of $248,077, and a QBI deduction of $49,615 (which was $6,000 higher than it was before Peggy decided to go back to work).

Now, imagine that Peggy decides to go full-time instead of part-time, and her salary doubles from $30,000 to $60,000. Would that result in another $6,000 of QBI Deduction-Production (the same as was generated from Peggy’s first $30,000) of salary) for the couple, reducing their effective tax rate on the income?

The answer is “no.”

After accounting for Peggy’s new $60,000 salary, the couple would have taxable income (prior to the application of the 199A deduction) of $278,077, while QBI would remain at QBI of $263,077. Here, the limiting factor would no longer be taxable income, but rather, the lower QBI amount itself. And therefore, the couple’s QBI deduction would be $263,077 x 20% = $52,615. Which is only $3,000 higher than before earning the extra $30,000 of income (not 20% x $30,000 = $6,000 of additional deductions).

As Example 4 shows, once Peggy’s salary (the couple’s only non-QBI eligible taxable income) reaches $45,000, equaling the couple’s non-QBI reducing deductions (which here, are simply the couple’s $45,000 of itemized deductions), the maximum QBI deduction is achieved, and an additional 199A Deduction-Production for additional income is no longer available. Further increases in taxable income are no longer be “subsidized” by a growing 199A deduction.

Using Roth IRA Conversions To Maximize 199A Deduction-Production Income

While there are certainly exceptions to the rule, in general, taxpayers whose 199A deductions are restricted by the deduction’s taxable income limitation should give serious consideration to finding ways to accelerate taxable income. Because by doing so, the resulting 199A Deduction-Production will cover the tax cost of some of that income, such that the income will only be taxed at 80% of its otherwise-applicable rate.

Taxpayers may have a variety of options at their disposal when attempting to engage in some good (not so) “old fashioned” Deduction-Production Income strategies, but without a doubt the best option for many will be to engage in Roth IRA conversions. As not only are Roth conversions that create 199A Deduction-Production subsidized by the corresponding increase in the 199A deduction, but such conversions also offer the benefit of protecting future growth from taxation as well (at what will likely be a favorable current tax rate, especially when that rate is only 80% of the otherwise-applicable tax bracket!).

Roth conversions also offer other, more practical Deduction-Production benefits as well. For instance, the income produced by a Roth conversion is easy to control. Simply decide how much to convert! Conversions are also easy to initiate, can generally be processed relatively quickly, and perhaps most importantly, can create income quickly.

Indeed, depending upon an individual’s IRA custodian, a Roth IRA conversion request might be able to be submitted up to and including December 31st of the year (the last day to make a Roth IRA conversion). Thus, even if a tax projection is completed on the final day of the year, if that projection suggests that the taxpayer would benefit from the acceleration of income to trigger a 199A Deduction-Production, it’s possible that a Roth IRA conversion can still be done in time to achieve the goal.

Example #5: Jack and Sandra are a married couple who file a joint tax return. Jack is 60 years old and retired, while Sandra continues to work in her sole proprietorship medical practice. As 2019 comes to a close, the couple meet with their financial advisor and CPA. Sandra estimates that she will net a $240,000 profit from her sole proprietorship, and Jack thinks they will have $38,000 in itemized deductions. Finally, Sandra intends to make a traditional IRA contribution for the maximum deductible amount of $7,000 for 2019 (including a catch-up contribution for being over age 50), plus an additional $7,000 for Jack as a spousal IRA contribution.

Based on the information provided by the couple, Jack and Sandra’s tax advisor calculates that they will have qualified business income from Sandra’s sole proprietorship of $228,546 (which is her $240,000 less the $11,454 of deductible self-employment taxes). The couple’s taxable income, prior to the application of the 199A deduction, is calculated as $176,546. After subtracting the $176,546 x 20% = $35,309 QBI deduction, the couple’s final taxable income is $141,237, giving them a Federal income tax liability of $22,789, and putting them right in the middle of the 22% bracket, which spans from $75,951 to $168,400 in 2019.

Suppose now, that in the context of the “to Roth or not” conversation, the couple believes that their future tax rate in retirement will be somewhere around 20%. Would it make sense to add more income now, even though they’re in the 22% bracket, which is higher than what they anticipate their future tax rate to be?

You betcha!

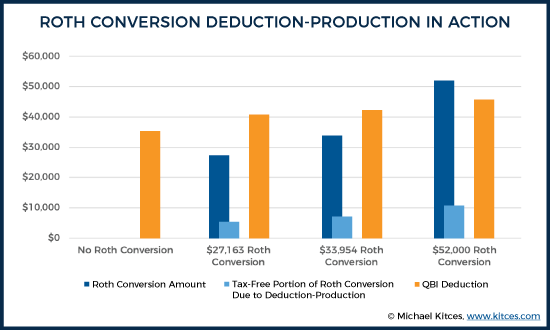

To illustrate how such a Roth conversion could benefit the Jack and Sandra, suppose that they executed a Roth conversion with the intent of maximizing their available bracket space within their current 22% bracket. Since the 24% bracket begins at $168,400 and their current taxable income is $141,237, that might lead one to think that adding another $168,400 - $141,237 = $27,163 of income via a Roth conversion would allow the couple to “top off” their 22%. But remember, as the couple’s taxable income increases, so too will their QBI deduction. Thus, a Roth IRA conversion of $27,163 will “only” increase the couple’s taxable income by $21,730 to $162,967. Instead, it will take a conversion of $33,954 to “do the trick” and bring taxable income (after the impact of the QBI deduction-production) up to the $168,400 top of the 22% bracket.

In reviewing the tax impact of the $33,954 conversion, Jack and Sandra’s Federal income tax liability increases from $22,789 pre-conversion, to a post-conversion total of $28,765. That’s a $5,976 increase, which translates to an effective tax rate on the conversion of $5,976 / $33,954 = 17.6%. NOT coincidentally, 17.6% is also equal to 80% times the tax bracket in which the income was taxed!

In fact, armed with this knowledge, if Jack and Sandra are “betting” on a future tax rate of 20%, their Deduction-Production Roth IRA conversion should be increased even further since going into the 24% bracket would also make sense, as 24% x 80% = 19.2%

Thus, Jack and Sandra can fully offset their $38,000 itemized deductions’ and $14,000 of total IRA contribution deductions’ reduction of their potential 199A deduction by converting a total of $52,000, pushing further into the 24% tax bracket (which is only a net 19.2% tax rate for them, thanks to the 199A Deduction-Production effect). This equalizes the couple’s taxable income, before the application of the 199A deduction, to their qualified business income of $228,546, allowing them to “max out” their QBI deduction at $45,709.

As the above example illustrates, income that generates a Deduction-Production effect ends out being taxed at 80% of the otherwise applicable rate. Which is not only easy to control via Roth conversions but can actually make Roth conversions more appealing precisely because the current Roth conversion rate is reduced (making it easier to stay below the projected future tax rate). However, it’s still important to bear in mind that any additional ordinary income added beyond the point that taxable income after deductions equals Qualified Business Income (or alternatively, the point at which other eligible income equals the couple’s various deductions), additional income would not result in any additional QBI deduction, and would therefore simply be taxable at “regular” (not-necessarily-appealing) tax rates.

Secondary Options For Deduction-Production Income

For those individuals who would benefit from adding more Deduction-Production Income, but who either don’t have enough traditional, pre-tax retirement funds to Roth convert to maximize its potential (or who can’t access those funds, perhaps because they are “locked up” in an employer’s 401(k) to which there is currently no access), other potential sources of ordinary income generation should be considered. One secondary option is to simply earn, or have a spouse earn, additional W-2 wages, as such income is taxable at ordinary rates, but is not itself, qualified business income eligible for the 199A deduction.

Notably, this is one reason why owners/employees of S corporations are less likely to benefit from the Deduction-Production strategy than partners or sole proprietors. Unlike the latter, S corporation owner/employees should already be receiving a reasonable, ordinary-income-but-non-QBI-eligible-salary, which also happens to reduce that chances that taxable income will be less than qualified business income (since the salary is other non-QBI taxable income to offset against available deductions). And when taxable income (including non-QBI salary) is greater than QBI from the business to begin with, there is no opportunity for Deduction-Production Income tax savings at all.

Of course, for those who are paying themselves a salary from their own business, earning W-2 wages means actually working, which in and of itself makes it less attractive than other options. A non-working spouse may not have any desire to (re)enter to the workforce in order to get a tax break, while a QBI-generating business owner may lack both the time and the desire to work another job.

Another potential source of Deduction-Production Income could be transitioning qualified-dividend-paying investments to ordinary-income-paying investments. Recall that the effect of Deduction-Production is to create an effective rate that is 80% of the actual rate. For instance, a filer in the 22% ordinary income bracket pays tax on qualified dividends at a 15% rate. But if that taxpayer is able to benefit from Deduction-Production Income, the ordinary income tax rate effectively drops to 17.6%, while the qualified dividend rate remains unchanged at 15%. Thus, the after-tax yield calculation shifts potentially making such a switch in investments more attractive, as the ordinary income yield would only have to be very slightly higher than the available dividend yield to be superior on an after-tax basis.

Other ways to engage in Deduction-Production Income include taking taxable distributions from non-qualified annuities, as well as simply adjusting the timing of certain deductions to not claim them in the current year when the taxable income limitation is in effect for a QBI deduction. For example, instead of making a December contribution to a favorite charity, a taxpayer might wait until January of the following year to make the same contribution, in order to allow the QBI deduction to be better maximized in the current year.

Deduction-Production Doesn’t Work (As Well) When The QBI Deduction Is Being Phased Out For Other Reasons

When considering whether it makes sense to engage in Deduction-Production Income strategies, it’s important to consider whether taxable income is the only factor limiting the amount of the QBI deduction. Because, in the end, the total amount of QBI deduction for which a person is eligible can be limited by a number of other factors as well.

For example, once an owner of a Specified Service Trade or Business (SSTB)’s taxable income begins to exceed the lower end of the phaseout range ($160,700 for single filers for 2019, $321,400 for joint filers for 2019), they begin to see their QBI deduction phased out regardless of whether taxable income is greater than, or less than, their QBI.

As an SSTB owner’s taxable income approaches the top of their phaseout range $210,700 for single filers for 2019, $421,400 for joint filers for 2019), it continues to be reduced. And once taxable income reaches the top of the phaseout range, the QBI deduction is eliminated altogether!

In such instances, adding more taxable income is not likely to help. In fact, it might even hurt! Because, in situations where an SSTB owner’s taxable income is less than their QBI, if adding more taxable income would push them (further) into or above the phaseout range, they may be trading one restriction on the deduction’s benefit for another that’s even worse.

High-income owners of businesses that are not SSTBs may also find themselves in the same position if they don’t have enough wages or depreciable property to cover a “full” QBI deduction. When such business owners have taxable income in excess of the top of their phaseout range, the maximum QBI deduction that they can receive is equal to the greater of 50% of wages paid, or 25% of wages paid plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis of depreciable property owned by the business (the testing is phased in for such business owner’s within the phaseout range).

Thus, for non-SSTB business owners with sufficient wages and/or depreciable property (such that their QBI deduction is not limited by the tests), Deduction-Production Income can be implemented in a manner similar to those business owners (SSTB and non-SSTB) with taxable income below the start of their phaseout range. However, for those high-income non-SSTB business owners whose wages/depreciable property have already been fully “absorbed” by the wage/wage-and-depreciable-property tests (and thus, have already “capped” the QBI deduction), Deduction-Production Income is no longer possible… and the addition of more taxable income for that purpose should be avoided.

The hallmark of good tax planning is to pay taxes when your rates are the lowest. All too often, however, people simply look at their taxable income, compare it to a chart showing the tax brackets, and assume that any additional income will be taxed at that rate. That’s not always the case though!

Many times, the addition of more income creates a tax rate that’s higher than the stated tax rate because the income is simultaneously eliminating some sort of deduction of credit. Occasionally, however, there’s a quirk in the law that can be exploited, allowing additional income to be taxed at what might be considered an artificially low rate. And one of the best examples of that in the current law is when a business owner’s facts and circumstances line up such that they can take advantage of additional 199A QBI Deduction-Production Income.

The Deduction-Production strategy effectively produces a tax rate that is “just” 80% of the rate that income would otherwise be taxed at. Thus, for this income acceleration strategy not to make sense, a business owner’s future tax rate would have to be at least 20% lower than their current rate. That’s an unlikely outcome for many successful business owners, making the Deduction-Production strategy today a home run! At least for those who are eligible, because their QBI deduction is being limited by their taxable income in the first place.