Executive Summary

In December 2017, Congress passed “comprehensive tax reform” via the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The law was a once-in-a-generation, massive rewrite of the Tax Code, and gave birth to IRC Section 199A, which allows certain owners of pass-through businesses to receive a deduction for up to 20% of qualified business income.

While the new deduction will be a powerful way for many business owners to reduce their tax liability, it comes at a price… complexity. Many tax experts believe that “new” IRC Section 199A is among the most complicated aspects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. And as evidence to support that claim, individuals can look no further than the IRS’s massive dump of Section 199A guidance on January 18, 2019. That trove of 199A guidance included 247 pages of Final Regulations and discussion, additional Proposed Regulations, IRS Notice 2019-07, and IRS Revenue Procedure 2019-11!

Critically, the introduction of the Section 199A deduction means that business owners must reevaluate their planning from the ground up, as even “obvious” decisions may need to be altered in light of the new rules. Case in point? Going forward, the Section 199A deduction will dramatically reduce the value of a tax-deductible retirement plan contributions.

This new “deduction-reduction problem” with pre-tax retirement contributions arises from the fact that the Section 199A deduction only applies to qualified business income, which is essentially the profits of a company. But when an S corporation makes an employer contribution to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, that contribution, itself, reduces corporate profits. Thus, there is less profit on which the 199A deduction can potentially apply. The sum of these moving parts is that, for some S corporation owners, a contribution to an employer-sponsored retirement plan will effectively result in a partial deduction, but still subject the entire contribution, plus all future earnings, to income tax upon distribution.

Prior to the issuance of the Final Regulations, it was widely assumed that this issue was only applicable to owners of entities taxed as S corporations, since contributions to retirement plans for sole proprietors and partners do not reduce business profits, but rather, are taken as personal above-the-line deductions on new Form Schedule 1 (formerly on the bottom of page 1 of Form 1040). The Final Regulations, however, make clear that sole proprietors and partners must also “back out” these amounts from business profits prior to the application of the 199A deduction. Thus, the “deduction-reduction problem” created by the Section 199A deduction will impact far more small business owners than previously thought.

In general, the primary reason a business owner should make contributions to a tax-deductible retirement plan (as opposed to a Roth-style plan) is that they believe that they are in a higher tax bracket today than they will be when they distribute those funds (along with their earnings) in the future. But when, in effect, you’re only getting a partial deduction for amounts contributed to a plan today, but still have to pay taxes on the “full boat” in the future, it changes the calculus quite a bit! Notably, for business owners who find themselves in this situation, their future tax rate must be even lower for the tax-deductible contribution today to make sense.

But just because a business owner isn’t getting the same bang-for-the-buck on a tax-deductible contribution doesn’t mean that they should throw in the tax-preferred-retirement-savings towel altogether! Instead, 401(k)s with a Roth-style option will simply become more valuable. And for those business owners looking to sock away more for retirement than the $19,000 maximum Roth 401(k) deferral ($25,000 if 50+ by year-end) for 2019, making after-tax contributions to the 401(k) plan (potentially to later convert under the “Mega-Back-Door Roth” strategy) can be an increasingly attractive option as well.

Of course, there is no -one-size-fits-all solution, and there are still plenty of business owners who will continue to benefit from tax-deductible contributions. Such business owners include those in Specified Service Businesses whose income is so high that the QBI deduction is phased out anyway (such as high-income financial advisors, doctors, lawyers, consultants, and accountants), those who believe that their future marginal tax rate will be significantly lower than the marginal tax rate they face today, and business owners who need to reduce their Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) to qualify for other deductions, credits, etc. (as the Section 199A deduction happens “below-the-line” and itself does not reduce AGI).

And of course, it’s important to recognize that tax-favored retirement accounts, in general, should not be abandoned altogether in light of the deduction-reduction impact of Section 199A. While the new deduction-reduction limitation definitely tilts the balance more towards Roth-style retirement accounts, the tax-deferred nature of all retirement accounts cannot be overlooked. Thus, even getting a partial deduction on a contribution today, while paying income tax on the full amount (plus earnings) in the future, will often be preferable than simply investing the same amounts in a taxable account where the entire contribution is implicitly taxed immediately (as an after-tax-dollars account) and then experienced further annual “tax drag” from interest, dividends, and capital gains.

Ultimately though, the most important thing for business owners and their advisors to realize is that the Section 199A deduction’s complexities go far beyond just the calculation of the deduction itself. Rather, there are ripple effects that make it necessary to take a fresh look at every element of a business owner’s overall tax plan, including which type of retirement plans will really provide the maximum benefit in the future!

From the beginning, trying to unravel the “inner workings” of the deduction and figuring out how to maximize its potential value has been of great interest to tax advisors, financial planners, and, of course, small business owners themselves. And for good reason, as the deduction impacts both a substantial number of individuals and has the potential to dramatically lower their taxes. Add to that the fact that the deduction is massively complex, and it's easy to see why it’s received so much attention.

To that end, many small business owners, along with their tax and financial advisors, were eagerly waiting for the release of the IRC Section 199A Final Regulations, with hopes that they would finally answer many, if not most, of the unanswered questions. Those “prayers” were answered just before the start of tax season for the 2018 tax year (nothing like having time to plan, right?!) when on January 18, 2019, the IRS released some 247 pages of Final Regulations (including background information), along with other supporting guidance, including additional Proposed Regulations, IRS Notice 2019-07 (dealing with how rental real estate can qualify as a “business” for purposes of the deduction), and IRS Revenue Procedure 2019-11 (which provides additional guidance on how to calculate wages for the wage/wage-and-depreciable-property tests).

The final regulations do, indeed, provide many of the answers that taxpayers were looking for. And as can be expected in such situations, some of those answers were favorable, while others were not. Notably, one big “negative” to come out of the final regulations is that they significantly expand the number of small business owners for whom there is now a reduced (yes, reduced!) incentive to make tax-deductible contributions to employer plans. In other words, the final regulations make clear that, for many business owners, the tax-deductible contributions they make to certain employer-sponsored retirement plans will be “worth” less. But to understand why, though, it is first necessary to have a “basic” understanding of how the 199A deduction is calculated.

“Basic” Mechanics Of The 199A Deduction Calculation

While there are nearly endless wrinkles, caveats and “yeah buts” to the 199A deduction (the likes of which are being “discovered” on an almost daily basis still), the “basic” mechanics around the calculation are fairly straightforward.

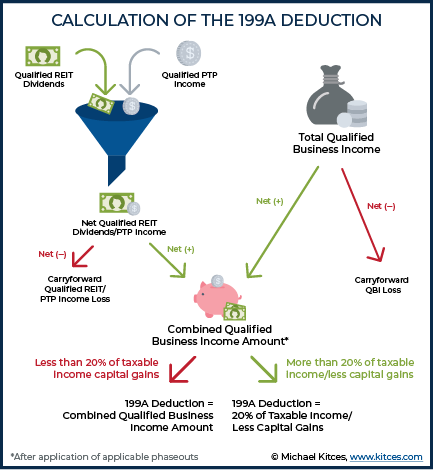

Owners of pass-through businesses (i.e., partnerships, S corporations, LLCs, and even sole proprietorships) are eligible to receive a 20% deduction on the lesser of their:

- Taxable income, reduced by capital gains (which includes qualified dividends), or

- Combined qualified business income (the sum of any positive qualified business income [after netting all qualified business income], plus the sum of any positive qualified REIT dividends and publicly traded partnership income [after netting all such investment income]).

For example, suppose an individual has combined qualified business income of $140,000 and taxable income (after the subtraction of capital gains) of $120,000. In such an instance, the 20% 199A deduction would be applied to the $120,000 of taxable income (the lesser of the two amounts), producing a deduction equal to $120,000 x 20% = $24,000.

Alternatively, suppose a second individual has combined qualified business income of $150,000 and taxable income (after the subtraction of capital gains) of $170,000 including their spouse’s wage income. Here, the 20% 199A deduction would be applied to the $150,000 of combined qualified business income (again the lesser of the two amounts) and would equal $150,000 x 20% = $30,000.

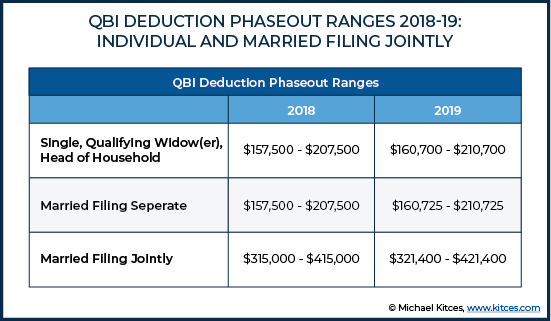

For “low income” taxpayers, the calculation of the deduction is as simple as that. And in further good news for taxpayers, for purposes of the 199A deduction, “low income” really isn’t that low at all. It applies for anyone in the bottom four tax brackets – 10%, 12%, 22%, and 24% – with additional restrictions and phaseouts only beginning once a household reaches the 32% tax bracket ($157,500 for individuals, $315,000 for married couples for 2018) as shown below:

For small business owners whose incomes cross into at least the 32% tax bracket (i.e., exceed the start of the phaseout range), the calculation of the 199A deduction becomes much (much, much, much, much… you get the point!) more complex. It requires, amongst other things, a thorough analysis of a business owner’s operations, including determining whether the business, or any “line” of business, will be deemed a “Specified Service Business,” determining the amount of wages paid by said business, and calculating something called “the unadjusted basis of depreciable property immediately after acquisition.” Thankfully, understanding how these calculations work is not necessary to understand how the new 199A rules reduce the incentive for some small business owners to contribute to tax-deductible employer-sponsored retirement plans, and thus, is beyond the scope of this article. (Though see here for a further discussion of the Specified Service Business and wage-and-property test restrictions on high-income pass-through business owners.)

How Deducting Retirement Contributions Can Reduce The Section 199A Deduction, Too

Shortly after the creation of the IRC Section 199A deduction, some tax practitioners came to a somewhat troubling realization for certain S corporation owners: they “discovered” that by virtue of the way the 199A deduction is calculated, it would reduce the value of making certain tax-deductible retirement plan contributions. The issue was that the 199A deduction is calculated based on net income, and those retirement contributions (e.g., SEP IRA contributions, employer matching contributions, profit-sharing contributions, etc.) would decrease the S corporation profits on which the 199A deduction was based. In essence, retirement plan contributions reduce the section 199A deduction, or conversely the 199A deduction turns the deduction for a business owner’s employer-sponsored retirement plan contributions into a partial deduction. Which is concerning not just for the limited deduction itself, but because the business owner will still have to pay tax on the full amount contributed to their retirement account when distributed in retirement!

Example #1: Robin is the sole owner and employee of The Woods, Inc., an S corporation. For the last several years, she has been making SEP IRA contributions equal to 25% of her salary (the maximum allowable percentage) into her SEP IRA.

In 2018, Robin paid herself (via The Woods, Inc.) a salary of $80,000, and prior to making any employer contributions to a retirement plan (i.e., her SEP IRA contribution), she has $90,000 of business profit as well (for a total take-home income of $170,000). Assuming Robin’s taxable income after itemized deductions is still greater than her $90,000 qualified business income amount – a likely scenario given the $80,000 of salary she took in addition to the profit – she would be entitled to a 199A deduction of 20% x $90,000 = $18,000 if she took no further action.

Suppose, however, that Robin decides to make her current-year SEP contribution equal to 25% of her salary, or 25% x $80,000 = $20,000. Will she receive a $20,000 SEP deduction?

Absolutely!

At least on the surface… but when you begin to take a closer look, a troubling picture begins to emerge.

Continuing with our example, let’s suppose that Robin does decide to make a maximum SEP IRA contribution for 2018 and contributed $20,000 to her SEP IRA. This reduces The Woods, Inc. profits to $70,000, so now, instead of being eligible for the original, pre-SEP-IRA-contribution, 199A deduction amount of $18,000, Robin is “only” eligible for a 199A deduction of 20% x $70,000 = $14,000 (on top of the $20,000 SEP IRA contribution deduction itself).

Here’s where it gets interesting…

In comparing our two potential scenarios for Robin (SEP IRA contribution vs. no SEP IRA contribution), we can see that Robin’s cumulative deductions (SEP IRA deduction plus 199A deduction) are $18,000 if she doesn’t make the SEP IRA contribution, and $20,000 (SEP IRA contribution) + $14,000 (reduced 199A deduction) = $34,000 if she does make the contribution. Thus, by making the $20,000 SEP IRA contribution, Robin has “only” increased her deductions by $16,000!

Clearly, the outcome above is not an optimal result, but here’s the really bad part… what happens when Robin goes to take a distribution of that $20,000 from her SEP IRA (plus whatever it’s grown to) later on in life?

That’s right! She’s going to owe tax on the full $20,000 contribution amount (plus any growth)! In a way, it’s almost like Robin is making a $4,000 nondeductible contribution to a SEP IRA (on top of a $16,000 deductible contribution), but not getting any credit for basis for having made that nondeductible contribution!

199A Final Regulations Expand The Retirement Contribution “Problem” To Sole Proprietors And Partnerships

After the creation of IRC Section 199A via the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and indeed, even after the release of the Section 199A Proposed Regulations on August 8, 2018, it appeared that the “problem” described above was limited to S corporations only.

After all, when a sole proprietor makes a contribution to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, they don’t get to reduce net Schedule C profits (which would also lower self-employment tax). Instead, the deduction is taken “as an individual” on their Form 1040 (an “above-the-line” personal deduction of the business owner instead). Similarly, partners in a partnership do not receive a partnership-level deduction for amounts contributed to an employer-sponsored retirement plan on their behalf and, like sole proprietors, claim that deduction on their Form 1040 (and also like sole-proprietors, do not get to reduce self-employment taxes on account of the deduction). Thus, in both situations, the business income of a taxpayer (Schedule C profits of a sole proprietor, and Box 1 Net Profits of the K-1 for a Partner) is not lowered by a contribution to an employer-sponsored retirement plan in the same manner it is for S corporation owners.

And given that business income for sole proprietors and partners is not reduced by contributions to employer-sponsored retirement plans on their behalf (as their personal income is lowered instead), it would be reasonable – and perhaps even logical – to assume that qualified business income (for the purposes of the Section 199A deduction) would not be reduced either. But reasonable and logical are not often words you hear associated with the tax code… and for good reason.

Indeed, in what came as a surprise to many tax experts (and by the looks of it, just about ever tax software provider), the 199A Final Regulations make clear that sole proprietors and partners DO need to make adjustments to net business profits to account for contributions to employer-sponsored retirement plans when arriving at the amount of qualified business income that is eligible for the 20% pass-through deduction.

Specifically, the new Section 1.99A-3(b)(vi) Of The Final Regulations states:

“Other deductions. Generally, deductions attributable to a trade or business are taken into account for purposes of computing QBI to the extent that the requirements of section 199A and this section are otherwise satisfied. For purposes of section 199A only, deductions such as the deductible portion of the tax on self-employment income under section 164(f), the self-employed health insurance deduction under section 162(l), and the deduction for contributions to qualified retirement plans under section 404 are considered attributable to a trade or business to the extent that the individual’s gross income from the trade or business is taken into account in calculating the allowable deduction, on a proportionate basis to the gross income received from the trade or business.” (Emphasis Added)

As a result of this new language, which was not included, nor alluded to, in the Proposed Regulations released in August 2018, the S corporation retirement contribution “problem” is now a problem for sole proprietors and partners as well!

Example #2: Marian is a sole proprietor who has net Schedule C profits of $107,602 for 2018. Thus, after subtracting out $7,602 to account for the deductible portion of Marian’s self-employment taxes (also required under the above regulation), but absent any further action, Marian has $100,000 qualified business income for 2018. Assuming that her taxable income is at least $100,000 (higher than her QBI), she will receive a 199A deduction of 20% x $100,000 QBI = $20,000.

Suppose, however, that Marian decides to make the maximum allowable contribution of $20,000 to her SEP IRA for 2018. Per the Final Regulations, this amount would need to be subtracted from the $100,000 total prior to the application of the 199A deduction. Thus, after such a SEP IRA contribution, Marian’s total QBI deduction would be $80,000 x 20% = $16,000. Which means the addition of the $20,000 SEP IRA deduction reduced Marian’s QBI deduction by $4,000 as well.

As is plainly evident, Marian, our sole proprietor, is going to find herself in a similarly sour predicament as the one that befuddled Robin in our earlier Example #1. Here, Marian’s pre-SEP-IRA-contribution combined SEP IRA/199A deduction amount is $20,000, while her post-SEP-IRA-contribution combined SEP IRA/199A deduction amount is not $20,000 + $20,000 = $40,000, but only $36,000 instead. Because Marian contributed $20,000 into a SEP IRA, yet received “only” a net $16,000 additional deduction amount due to the partial loss of the QBI deduction alongside it.

Understanding The QBI Impact Of The “Partial” Retirement Plan Contribution Deduction On Future Taxes

While there are exceptions to just about every rule, and this one is no exception, the number one rule for taxes, and a hallmark of a good tax planning, is to try and pay taxes when your rate is lowest. The flip side of that argument is to try and claim deductions when your income is highest, because, with deductions, the “value” of a deduction generally varies in direct proportion to the marginal tax rate to which you find yourself subject.

By contrast, a tax credit is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in one’s taxes. Thus, a tax credit is worth the same amount regardless of the marginal income tax rate to which you’re subject. Have a $500 credit but you’re “only” in the 12% bracket? Well, you just saved $500 on your tax bill. Have a $500 credit and you’re in the 35% tax bracket? Well, you too save the same $500 on your taxes.

Yet a $5,000 deduction for someone in the 35% tax bracket is worth $1,750. Meanwhile, the same $5,000 deduction would “only” be worth $600 for someone in the 12% bracket.

While those concepts are fairly easy to understand, analyzing how the “partial deduction” that many business owners will now receive for tax-deductible retirement plan contributions is a little bit trickier. Consider the following simplified example to illustrate the point:

Example #3: Recall Marian from our previous example, the sole proprietor who had $100,000 of qualified business income prior to making her SEP IRA contribution. Let’s further assume that her total taxable income is $105,000, including a small amount of wages earned from part-time work. As a single filer, this puts Marian squarely within the 24% tax bracket for 2018.

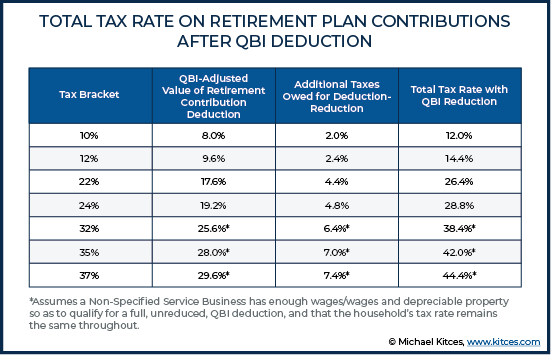

Further recall that by making a $20,000 SEP IRA contribution, Marian would receive a net $16,000 deduction, due to the reduction of her 199A deduction. As such, the net tax savings to Marian of making her $20,000 SEP IRA contribution is $16,000 x 24% = $3,840.

Now suppose that Marian’s income looks substantially similar for 2019, but that she decides to take a distribution of that $20,000 SEP IRA to pay for a dream vacation. The $20,000 distribution from the SEP IRA will increase Marian’s income by a full $20,000, which at a 24% rate will cost her an additional $4,800 in taxes.

As the example above illustrates, Marian would have been much better off not making the SEP IRA contribution in the prior year, and simply keeping that $20,000 and paying the additional $3,840 dollars she would have had to pay (by not getting the SEP IRA contribution deduction), rather than waiting a few months and paying nearly $1,000 more on the same $20,000 of cash! In fact, for every dollar of deduction Marian was receiving on her SEP IRA contribution, she will ultimately pay tax on $1.25 ($20,000 / $16,000)!

Or viewed another way, those who are also eligible for the QBI deduction will only get to claim a deduction for 80% of the funds contributed to a deductible retirement account, while still paying taxes on 20% of the income today, even though they’ll still have to pay taxes on 100% of the income in the future as well! Which means the higher the tax rate to which the deduction-reduction is applied at contribution, the more in additional taxes that will be incurred cumulatively (an additional part now, plus the rest that would already be due in the future) from the partially-lost deduction!

The knee-jerk reaction upon understanding this phenomenon is to jump to the conclusion that pretax retirement accounts for business owners like Marian are no longer a viable strategy. As choosing to contribute to a retirement account when also eligible for the QBI deduction (and subject to its impact) literally reduces the value of the deduction by requiring the business owner to continue paying taxes on 20% of the otherwise deductible amount.

The reality, however, is that such determinations still need to be made on a case-by-case basis. In many instances, it will become far more preferable to contribute to Roth accounts instead (or even after-tax retirement accounts that are converted to Roths later), though in many situations business owners should continue making their usual tax-deductible contributions (particularly if they’re not actually going to be able to claim the full QBI deduction anyway!).

Maximizing Roth Options For Business Owners Impacted By The QBI Deduction-Reduction

For business owners who expect to be in a similar (or worse yet, a higher) tax bracket in the future than they are today, the best course of action may be to try and make the most of Roth-style retirement accounts instead.

By utilizing a Roth retirement account option, there is no deduction for the contribution… which means there is no 199A deduction-reduction either. Yet thanks to the Roth “wrapper” (as opposed to simply not making a retirement account contribution at all), future dividends, interest, and capital gains are shielded from annual taxation.

Unfortunately, though, there aren’t many Roth options when it comes to employer-sponsored plans. In fact, pretty much the only game in town is the 401(k) with a Designated Roth Account feature added in (also simply known as a “Roth 401(k)”).

In 2019, such plans generally allow up to $19,000 of salary to be “deferred” into the Roth side of the plan. For those 50 or older by the end of the year, that amount is increased to a maximum of $25,000 with the $6,000 catch-up contribution.

Unfortunately, though, this highlights one of the real “problems” with the Roth 401(k) option; that it only allows a limited amount of funds to be put aside on a tax-favored basis, at least compared to pre-tax options, such as profit-sharing on top of a pre-tax salary deferral or SEP IRA contributions that can potentially go all the way up to the IRC Section 415 limit of $56,000 in 2019.

Leveraging After-Tax Contributions To A 401(k) To Mega-Backdoor-Roth Around The QBI Deduction-Reduction

For small business owners who expect to be in a similar or a higher marginal tax bracket later and want to contribute more than just the Roth 401(k) salary deferral – particularly sole proprietors and S corporation owners who are also the only employee – but want to avoid the QBI deduction-reduction that would apply on profit-sharing or similar contributions, it may be appealing to consider after-tax contributions to the 401(k) plan instead. In essence, specifically choosing not to make a deduction contribution, and make a non-deductible contribution instead.

The reason is not simply that by making an after-tax contribution, the small business owner at least preserves basis (avoiding the QBI deduction-reduction effect), but that in the future, the business owner may be able to convert those after-tax amounts into a Roth IRA… also known as the “Mega-Back-Door Roth” strategy.

The standard version of the Mega-Back-Door Roth requires a 401(k) plan that allows after-tax contributions to be made to the traditional side of the plan, in addition to any “regular” deferrals of salary, with an intention to convert them later to a Roth. Since the contributions are all after-tax, they can be converted tax-free, and since IRS Notice 2014-54, it is permissible to just convert after-tax dollars in a 401(k) plan (while rolling over any remaining pre-tax amounts to a traditional IRA).

Notably, the after-tax contributions are limited to the difference between the Section 415 overall annual limit ($56,000 for 2019), and the total of all contributions already made to the plan (and the total amounts also must be no more than the plan participant’s total compensation). Thus, a participant who has maxed out on $19,000 of salary deferrals in 2019 could add up to another $37,000 of after-tax contributions (as long as the employee earned at least $19,000 + $37,000 = $56,000 in the first place). However, small business owners should be cognizant that such contributions may also be limited by the Actual Contribution Percentage test, even in plans that utilize Safe Harbor options (though there is no such testing necessary for solo 401(k) plans).

At first glance, some may question the “need” for the added complication of adding a provision for, and then making, contributions of after-tax dollars to a 401(k) plan (and then going through the subsequent trouble of completing the Mega-Back-Door Roth). If Roth money is the goal, why not simply take an easier route, such as making contributions to a SEP IRA or profit-sharing plan and then just immediately converting them?

The short answer? Because in many cases, it will not be as tax efficient to do so with pre-tax contributions that are later Roth converted! Ironically, it takes contributing and converting after-tax dollars to avoid the adverse effect of the QBI deduction-reduction!

Example #4: Allan is the owner and only employee of Sherwood, Inc., an S corporation. In 2019 he estimates that he will pay himself $160,000 in salary, and will also have $100,000 in S corporation profits, prior to making any contributions to an employer-sponsored retirement plan.

In the past, Allan has always used a SEP IRA as his plan of choice for retirement contributions. However, in light of the change in Allan’s projected marginal tax rate through 2026 and the deduction-reduction effect, he and his tax planner have decided to evaluate the merits of using a combined Roth 401(k)/Mega-Back-Door Roth instead of the usual SEP IRA. Here are the results of their comparison:

Scenario #1: Allan contributes the maximum $160,000 x 25% = $40,000 allowable contribution to his SEP IRA for 2019, and then immediately converts it to a Roth IRA. If such action is taken, the following will occur:

- Allan’s $40,000 SEP IRA contribution will reduce his corporate profit to $100,000 - $40,000 = $60,000.

- Allan will receive a 20% x $60,000 = $12,000 199A deduction

- The total business-related ordinary income on which Allan will have to pay taxes in 2019 will be $160,000 salary + $40,000 SEP IRA contributions that is converted + $60,000 profit - $12,000 199A deduction = $248,000.

Scenario #2: Allan ditches the SEP IRA in favor of a 401(k) plan with a Roth feature. He “defers” $19,000 into the Roth 401(k), and then makes an additional $21,000 of after-tax contributions to the traditional side of the plan (thus equaling the same $40,000 Allan saved in a retirement account in scenario #1 above). Shortly after making the after-tax contributions, Allan does an in-service distribution of those amounts and converts them, tax-free, to a Roth IRA. If such action is taken, the following will occur:

- Allan’s corporate profits will remain $100,000

- Allan will receive a 20% x $100,000 = $20,000 199A deduction

- The total business-related ordinary income on which Allan will have to pay tax in 2019 will be $160,000 salary (no reduction for Roth 401(k) contributions or after-tax contributions) + $100,000 profit - $20,000 199A deduction = $240,000.

Note that by changing Allan’s plan to a 401(k) and giving the plan the “right” options (i.e., the ability to make after-tax contributions and the ability to take in-service distributions of those amounts), his taxable income for 2019 would be reduced by $8,000. In other words, normally most solo 401(k) owners would make profit sharing contributions to their 401(k) before resorting to making after-tax contributions to fill up any remaining room, but since profit-sharing contributions are always deductible, those pre-tax contributions are now to be avoided – at least for those in situations similar to that of Allan – in light of the QBI deduction-reduction in lieu of making after-tax contributions instead!

And further note that the result can be achieved with a near-identical outcome for Allan ($40,000 directly into a Roth IRA in scenario #1, versus $40,000 indirectly into Roth accounts in scenario #2 via $19,000 in a Roth 401(k) and $21,000 in a Roth IRA).

Of course, it's worth pointing out that the example above primarily addresses what business owners should consider doing if they believe that they will be in a similar or higher tax bracket in the future. And thanks to the temporarily-lowered-through-2026 Federal income-tax rates and the potential application of the 20% QBI deduction for at least some business income, that group of business owners is likely much bigger today than in the recent past.

Still, there may be some business owners who would like to make deductible contributions as long as they can receive a full deduction (one that is not subject to the effects of the deduction-reduction), even at today’s lower rates. For S corporation owners like Allan, from Example #4 above, one solution might be to maximize contributions to the “regular” side of a 401(k) plan. Such contributions would still reduce taxable income, but because salaries paid to S corporation owners (and anyone else) are already excluded from QBI, there is no further reduction in the QBI amount. Of course, such contributions would still be subject to the $19,000 ($25,000 if 50 or older by year-end) salary deferral limit, so the Mega-Back-Door Roth would continue to be necessary to save additional amounts on a tax-favored basis without falling prey to the impacts of the deduction-reduction.

Finally, it’s important to note that while this approach would almost certainly work for S corporation owners, it is not yet clear how the same strategy would impact partners – and to an even greater degree, sole proprietors – who do not (and cannot) pay themselves a salary.

Identifying Business Owners Who Should Continue To Utilize Tax-Deductible Retirement Options

The 199A deduction-reduction is not good news for any business owner. Frankly, no one wants a deduction for only $0.80 on the dollar but still have to pay taxes on the whole $1 in the future.

Nevertheless, despite the reduced value of the deduction for the retirement contribution, there are still quite a number of scenarios where that reduced benefit will still be better than any other practical alternative.

Business Owners Who Cannot Claim The 199A Deduction Anyway

Thanks to the fairly generous income thresholds at which the Section 199A deduction begins to phase out for taxpayers, many small business owners – of all sorts of businesses – will be eligible to claim the deduction. However, for high-income business owners of Specified Service Businesses (i.e., health professionals, legal professionals, accountants, financial advisors, consultants, athletes, and artists), the Section 199A deduction attributable to income from those businesses is completely eliminated once the top of the phaseout range has been reached.

And while the phaseout of the Section 199A deduction is bad news for the deduction itself, it means individuals with income in excess of the phaseout range still receive a full deduction for contributions to employer-sponsored retirement plans… because there is no longer any more 199A deduction for that retirement contribution to offset!

High-income business owners of non-Specified Service businesses may also find themselves in a similar predicament if they neither pay wages nor have depreciable property, and thus are unable to “protect” or claim any of their QBI deduction. Finally, business owners who have their deduction partially phased out will naturally experience the deduction-reduction effect to a lesser degree.

Business Owners Who Expect To Be In A Substantially Lower Tax Bracket In The Future

Those who are in one of the higher brackets today but expect a material drop in income (and marginal tax rate) in their future retirement may still be better off taking the partial deduction today, even if it means paying tax on the full amount in the future.

Whether or not this will ultimately make sense, however, will depend upon how far their tax rates drop in the future. At a minimum, their future tax rate must drop by at least 20% of what their tax bracket is today, simply to offset the direct impact of the QBI deduction-reduction.

Example #5: Will is a business owner of a non-Specified-Service business which owns $4,000,000 in depreciable property and generates $200,000 of qualified business income (after the reduction for one-half of self-employment insurance). By virtue of his substantial investments in depreciable property, Will’s Section 199A deduction is not limited by the wage/wage-and-depreciable property tests, which means he can claim the full amount.

Will’s wife is an executive at a large company, and earns a substantial income as well. Together they find themselves well into the top 37% tax bracket.

Assume that Will makes a SEP IRA contribution of $40,000 to a SEP IRA. By virtue of the fact that it will reduce his qualified business income that is eligible for the Section 199A deduction as outlined in the examples above, Will would effectively receive a net tax deduction of only $32,000. At the 37% tax rate, that would save Will $11,840 in Federal income taxes (or conversely, it would save him 29.6% of his original $40,000 contribution).

Suppose that the following year, Will and his wife both decide to call it quits. They’ve worked long enough and hard enough to accumulate enough money for retirement and are tired of the daily grind. Assuming their taxable income dropped to “just” $275,000 during their first year of retirement, they would find themselves in the “low” bracket of 24%.

As a result, if Will were to distribute the $40,000 of income he deferred the prior year, he would owe income tax on the full $40,000 amount. But a 24% tax rate on $40,000 produces a tax bill of “only” $9,600. Thus, Will still comes out ahead, because in this case, his partial deduction for the SEP of 37% on $32,000 (equivalent to a rate of 29.6% on the whole $40,000) that saved him $11,840 in taxes was still an improvement when he only had to pay $9,600 in subsequent taxes on that $40,000 at a 24% tax rate in the future!

Business Owners Who Need To Reduce AGI To Qualify For Other Deductions, Credits, And Benefits

One important caveat for planners to consider is that that while a small business owner’s (employer-side) contributions to employer-sponsored retirement plans reduce AGI (either as an above-the-line deduction on the 1040 for sole proprietors and partners, or by reducing corporate profits to S corporation owners, which lowers their gross income to begin with), the 199A deduction itself does not reduce Adjusted Gross Income. Instead, even though the Section 199 deduction is not an itemized deduction, it does happen “below the line” (technically, it is claimed after calculated AGI alongside itemized deductions), such that it does not reduce AGI.

As a result, those individuals who find themselves in a scenario where dropping AGI could have a material impact in receiving other tax/financial benefits may find employer retirement plan contributions appealing despite the impact of the QBI deduction-reduction.

For example, a (partial) SEP IRA contribution might reduce an individual’s Section 199A deduction, but if that drop in AGI gets them below a Medicare Part B IRMAA threshold, the trade-off might be worth it.

Unfortunately, there’s just not a one-size-fits-all answer here, as there are numerous benefits tied to AGI/MAGI, such as a variety of deductions and credits (including medical expense deductions, various college tax credits, and the child tax credit), the aforementioned Medicare Part B (and D) premiums, and the amount of Social Security benefits that are taxable. Many local jurisdictions also offer certain benefits, such as property tax breaks, tied to (Federal) AGI. Thus, a thorough analysis of each individual’s situation must be made prior to arriving at any “contribute or not” decisions.

Don’t Discount The Tax-Deferred Nature Of Retirement Accounts

In light of the deduction-reduction, some practitioners have speculated whether certain small business owners should simply avoid making retirement contributions altogether. It’s a reasonable thought, but the reality is that would very rarely result in long-term tax savings for the business owner.

Recall that the tax-deductible nature of contributions to certain retirement accounts is only one of their benefits. In addition to the up-front deduction though, the funds within the account are shielded from ongoing taxation. Thus, interest, dividends and capital gains can all be reinvested without any “tax drag.” This tax drag is substantial for many investors utilizing after-tax accounts as investment vehicles and can be exacerbated by even modest amounts of portfolio turnover.

Accordingly, while the impact of the QBI deduction-reduction does overwhelmingly make Roth-style retirement accounts preferable to pre-tax retirement accounts, it doesn’t necessarily make pre-tax retirement accounts irrelevant altogether.

When the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed in December 2017, it was clear the law would have a vast impact on a wide variety of taxpayers for years to come. Indeed, even now, more than one year later, the ripple-effects of some of its provisions, such as the new 199A 20% pass-through deduction, are only beginning to be fully understood.

And one of those wrinkles that has now been highlighted by the Final Regulations is the impact of the Section 199A deduction on the optimal retirement savings strategy of business owners. Due to the retirement contribution deduction-reduction effect caused by the 199A deduction, it’s possible to receive what is effectively a partial deduction today for amounts contributed today, even as those dollars will still be subject to full taxation on the same amount when distributed in the future (even if just a single day or year later).

Thus, it’s incumbent upon business owners and their financial professionals to understand these impacts and to determine if any changes to their overall plan, such as a change from a SEP IRA to a Roth 401(k) or making after-tax contributions to a traditional 401(k), would provide greater value instead.