Executive Summary

In most financial advisory firms, compensation for employees is more than 3/4ths of a firm’s total expenditures. Which means trends in compensation can have a very significant impact on the profitability and success of an advisory firm business. And the urgency of advisory firms to control compensation have become acute in recent years, as a projected wave of advisors retiring and a dearth of young advisor talent suggests that advisor compensation will rapidly rise, squeezing the margins of most firms.

Yet the latest industry benchmarking studies from Investment News and FA Insight find that, despite the fact that the headcount of financial advisors has already declined by 15% in the past 6 years, advisor compensation growth has remained remarkably sluggish, with little evidence whatsoever of an advisor talent shortage.

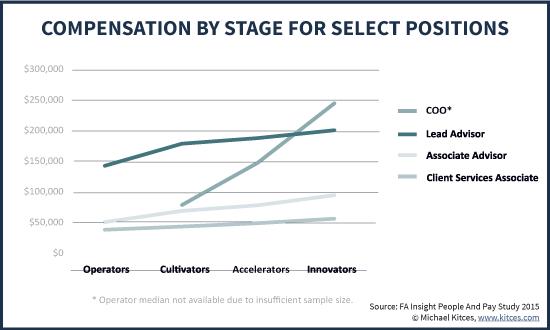

Instead, the industry studies find that the largest advisory firms are competing for talent by paying healthy salaries, supported by incentive compensation that allows them to be flexible in a bear market, and using their offer of a career track as an incentive to attract the top young talent. In the meantime, the firms are paying very modest raises, counting on the top advisor talent to satisfy their hunger for financial success by climbing the firm’s career track ladder from support advisor to associate to lead advisor, and ultimately to partner.

In fact, the lack of any apparent pressure on firms to raise compensation, despite what is already a declining advisor headcount, suggests that perhaps the reality is most of the current attrition of “financial advisors” are actually product-centric “non-advisors” who aren’t really delivering financial planning anyway. Similarly, the continued growth of CFP certificants – now up 54% in the past decade – may have actually been more than enough to satisfy the demand of firms for young talent as planning-centric firms slowly but steadily take market share. And with the average age of an employee lead advisor at planning-centric RIA firms “just” age 50, perhaps the reality is that the advisor talent shortage really is just a mirage – or at least, a danger that may not manifest for 10-15 years or more!?

Slowing Growth In Average Financial Advisor Salary And Other Cash Compensation?

The Investment News Compensation and Staffing Study (formerly driven by Moss Adams, now sponsored by Pershing and produced by Philip Palaveev and his team at The Ensemble Practice) and the FA Insight “People And Pay” Study are two of the longest standing benchmarking surveys analyzing trends in how much financial advisors make in cash and other compensation (along with the other staff members in advisory firms). And in their latest studies, a striking “new” trend is emerging: growth in financial advisor salary compensation appears to be remarkably sluggish, despite continued growth of advisory firms, and record highs in both advisor productivity and advisory firm profit margins.

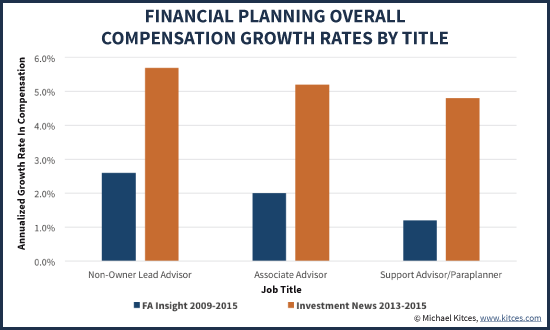

According to the FA Insight study, non-owner Lead Advisor compensation (there are now more non-owner employee advisors than there are advisor firm owners!) has experienced annualized growth of only 2.6% since the market bottom in 2009. Associate advisors have fared even worse, with average annual compensation growth of only 2%, and support advisors (i.e., paraplanners) have struggled even more, with compensation gains of only 1.2% over the past 6 years. To put that in context, the general growth for all U.S. wage and salary workers over the same time period was 2.0%!

And the Investment News study paints a similar picture as well. Over the past 2 years, the median salary for a non-owner lead advisor (i.e., an advisor who is primarily responsible for a group of clients, but is not a partner/owner of the firm) has grown from $110,000 to just $115,000, a compound growth rate of just 2.2%/year. Including bonuses and other incentive compensation, median total cash compensation for lead advisors went from $128,000 to $143,000, a slightly heathier 5.7% growth rate, but that compensation boost may be ‘temporary’, as bonus compensation for lead advisors is most commonly tied to AUM and revenue (that benefits from the bull market, but can evaporate quickly in the next bear market).

And according to the Investment News data – similar to FA Insight – the situation is only slightly better for Associate advisors, whose median salary went from $65,000 to $72,000 and total cash compensation grew at 5.2%/year. And once again, Support advisors (i.e., paraplanners) fared the worst, with median salaries rising from $50,000 to $55,000 and total compensation growing at only 4.8%/year.

Growing Your Income As A Financial Advisor By Climbing Up The Career Track Ladder

Of course, the caveat to these charts is that the most successful advisors in each category, who ostensibly would earn the biggest raises, don’t remain in that category in the first place – they tend to move up the line, as support advisors become associates, the associate advisors become lead advisors, and the best lead advisors have the opportunity to become partners. So the advisors who remain in each category tend to be the below-average performers.

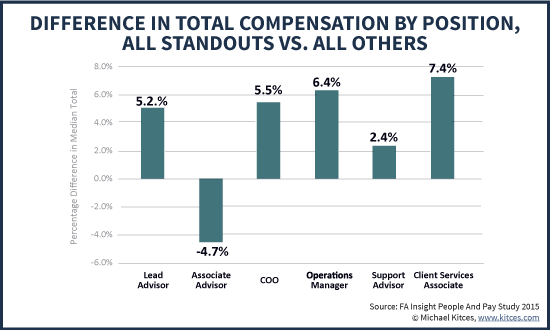

But still, increasingly in advisory firms, it appears the path to greater income is not to earn more in your current advisor position, but to learn the skills necessary to climb the career track ladder. In fact, amongst the most profitable and successful advisory firms, offering a career track with progression to the highest tiers of income seems to be used as a means to control compensation; consequently, the top performing firms pay barely more than other firms when it comes to a support financial advisor's salary, and actually pay less for associate financial advisor salaries, but use the potential of an upwards career trajectory along the firm’s career track to attract and incentivize the top young advisor talent (an area where smaller firms struggle to compete because they lack the size and depth and have too much uncertainty about growth to commit to a career track in the first place).

Overall, the opportunity to progress income by climbing the career ladder – rather than simply staying stationary and waiting for the raises to come – isn’t necessary a bad thing, and given recent growth of advisory firms there should certainly be ample opportunity for most successful advisors to move up. Yet in the meantime, the strategy of incentivizing advisors not with raises in their current positions but the potential to move up the ladder is simultaneously allowing advisory firms to control their costs, and leverage the productivity of their advisors (the average amount of revenue per professional in an advisory firm has leapt from $363,600 in 2009 to $528,500 by the end of 2014, a growth rate of 6.4%) while the advisory firm accrues the benefit of greater productivity.

Accordingly, advisory firms have improved profit margins from a median of just 14.2% in 2011, to a whopping 26.1% in today’s environment, by keeping advisor raises modest and allowing the top advisors to climb the career ladder instead! Though in the meantime, this still means the growing financial success of advisory firms is increasingly accruing to the owners of the firms, and not their advisor employees, and that advisors who want to reach the top of the income ladder must learn both the client relationship management and business development skills necessary to “make partner” at their firms!

Compensation Gains For For COOs And Other Non-Advisor Employees – Large Firms Pay More

Notably, while the compensation gains have been lackluster for the employee financial advisor positions at many advisory firms, the results have been quite a bit better for non-advisor employees, as the typical advisory firm continues to grow, becomes more complex, and requires more professional management and higher-level staff support.

For instance, FA Insight finds that the position enjoying the most compensation growth for the past 6 years – a whopping 6.9% per year – is the Chief Operating Officer (COO) position in the subset of firms that are becoming large enough to need one. The growth appears to be most significant at smaller firms that are growing large; in the Investment News data, the COO compensation growth has been flatter, but the typical COO in the Investment News data set already earns 35% more than their FA Insight counterparts. This significant compensation different appears to be due to the fact that the Investment News study has greater representation of mega-RIAs (what the study has dubbed “Super Ensembles”) that tend to offer the highest compensation. Similarly, due to the complexities of large firms, the Investment News study also shows that Chief Compliance Officer compensation (primarily found in large firms) has exploded at a 13% per year growth rate for the past few years!

Amongst other staff positions at mid-sized versus large advisory firms, a similar trend emerges. The slightly-smaller-average-firm-size FA Insight study finds Office Manager compensation has been up 3.9%, while Investment News shows it to be fairly flat. The same is true for Client Services Associations (up barely 2% in Investment News but over 4% with FA Insight). But again, the Investment News data, which has more large firm representation, has most of these staff positions getting smaller raises are already earning far more than their counterparts in the slightly smaller firms represented by the FA Insight data.

In fact, the overall trend becoming apparent in the advisory industry is that larger advisory firms are starting to pay noticeably more in compensation than smaller firms, though the higher compensation at those larger firms also means they’re under less pressure to give significant raises to staff members.

In turn, this suggest that reality in the FA Insight study is that a portion of the higher compensation growth may simply be because there are more small-to-mid-sized firms that have grown to become mid-to-large-sized firms in the past 6 years, and therefore have provided more compensation increases, simply because of this phenomenon that larger firms tend to pay more than smaller firms (and especially for non-advisor staff positions, as shown below). In other words, even for non-staff positions, advisory firms aren’t giving better raises due to a talent shortage and a struggle to find good people, but simply because they’re growing larger and the greater complexity of the job merits a greater compensation commensurate with those duties.

Is The Financial Advisor Talent Shortage A Mirage?

More broadly, perhaps the most notable aspect of the relatively slow growth in advisor compensation is that it wasn’t “supposed” to be this way. As many industry commentators and analysts have written for years, the advisory industry has a severe “demographics” problem, with the average age of an advisor at 50-something (from early 50s to late 50s, depending on which subset of data you look at), and a severe dearth of advisors in their 30s and especially Millennial advisors in their 20s. The implication for years has been that if/when/as advisors begin to retire en masse, there will be far too few advisors to replace them, and in turn compensation for employee advisors would rise dramatically due to the supply/demand imbalance.

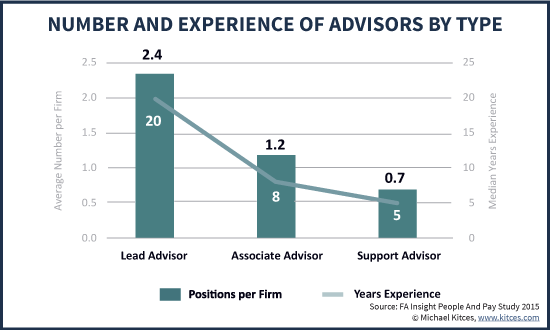

And this lack of a talent pipeline does still appear to bear out in the research. For instance, FA Insight finds that at the typical advisory firm, there is only 1 associate advisor available to replace every 2 lead advisors, and in turn there is an average of barely more than 1 support advisor for every 2 associate advisors! Which means if/when/as lead advisors actually do begin to retire, firms will suddenly experience an acute talent shortage, with only 2 associate advisors to replace every 4 lead advisors who leave, and only 1 support advisor to replace those 2 lead advisors!

Yet the reality is that the number of financial advisors has already been declining by a few percentage points per year – there were an estimated total financial advisor headcount of nearly 350,000 back in 2000, which had declined to 334,000 by 2009, and has accelerated down to only 285,000 advisors in 2014. And despite these declines that have already been occurring, the compensation impact of the implied “advisor shortage” has failed to appear.

Instead, to the extent that advisors are leaving the industry, apparently their clients are simply being “redistributed” (i.e., are finding their way or being to, or being outright acquired by) other advisors still in practice, resulting in a significant increase the amount of revenue being managed by the typical advisor, but little associated compensation increase!

The Attrition Of “Non-Advisor” Advisors And The Rise Of Financial Planning

Ultimately, the question that gets raised in all of these trends is whether the number of true “financial advisors” has perhaps been overstated in the first place, such that fears over the projected advisor attrition has been overblown.

For instance, a study from Cerulli several years ago found that only about 30% of “financial advisors” actually deliver real financial planning services to clients, which appears consistent with the fact that only about 25% of all financial advisors actually have CFP certification (with about 285,000 financial advisors and 72,600 CFP certificants according to the CFP Board). And notably, the number of CFP certificants is up significantly in the past several years (growing 54% in the past decade) even as the number of “financial advisors” declined by almost 15%.

In other words, perhaps the reality is that attrition in the number of “financial advisors” has been driven primarily by product-centric advisors, who weren’t really “true” financial advisors and weren’t delivering financial advice, and perhaps even retired because they were finding it increasingly difficult to compete. After all, even Cerulli notes that most of the projected advisor attrition is projected to come from the industry’s most product-centric channels, including wirehouses and broker-dealers, and not the increasingly-financial-planning-centric RIA channel.

In this context, the muted compensation growth of financial advisors in these RIA-centric benchmarking studies – firms that are generally really doing financial planning – suddenly makes far more sense. In these firms, the average age of an employee advisor is “only” 50 and retirement is still far away, the number of true financial planners retiring is happening less rapidly than anticipated (especially given both the financial and personal rewards of continuing to engage with clients), and in fact firms are growing as clients are slowly redistributing from product-centric non-advisors who are retiring. And no doubt, the increasing quality of technology solutions for advisors is also playing a role in allowing advisors to handle more financial planning clients than ever both.

Ultimately, then, what this suggests is that the real story in the advisory industry is perhaps there’s not an emerging acute advisor shortage, and the number of “real” financial advisors is growing at a steady and healthy pace, enough to keep up with the market demand – as evidenced by both the growth of CFP certificants, the lack of accelerating compensation increases, the leveraging of advisor technology tools, and the continued strong growth of financial-planning centric advisory firms!?

In the meantime, you can purchase a full copy of the FA Insight “People And Pay” Study and the Investment News Compensation and Staffing Study directly from their respective websites, if you want to check them out in further detail!

So what do you think? Is the young financial advisor talent shortage just a mirage? Are we actually creating enough young financial planners earning CFP certification to keep up with the demand? Is the attrition of financial advisors really just the retirement of product-centric "advisors" who are struggling to keep up in an increasingly financial-planning-centric world?

There are no shortages when free market’s are present. Supply meets demand at a given price and continuously seeks equilibrium. Why do you think there is a “shortage” of labor for advisors? Unless someone is setting the price artificially low, the supply demanded is being met.

Because these are markets that cannot equalize instantaneously. It takes years to train a new advisor from scratch to be capable of handling clients without supervision. So if a wave of senior advisor retirees hits, it can take 5-7 years for the replacements to be trained, which creates a severe supply/demand imbalance in the interim.

I don’t think that’s the way it works. That is the way it would work if somehow this changing of the guard from Boomer advisors to Nextgen were a surprise to the market. It isn’t. I’ve been hearing about this for a decade. If more labor were demanded for this job, wages for the right age workers would have begun rising very early in their careers, thereby inducing even more advisors. Remember too that if wages rise enough, others, CPA’s, lawyers, will retool their skills and supply more labor. There are no shortages in well informed and good functioning markets. There is only the nexus of supply and demand. Perhaps in the case of some big surprise. (like a techology shift)

And we know this isn’t a particularly efficient market. This is reflected in the parallel conversations on this blog around business models and pricing structures. A large number of consumers don’t even know what real financial planning is and how much they should be paying for it. And even in the best of circumstances, a consumer isn’t going to know or appreciate the efficacy of the advice received until many years after it is delivered. All of this is reflected in advisor compensation, which, as stated at the beginning of this piece, consumes 75% of revenues.

Interesting. New Zealand (population 4.6 million) was only recently regulated (2010), but the way its regulation works may provide insights into number of financial planners and other kinds of financial advisors.

All New Zealand financial advisors (FAs) – other than those working for large, self-regulating entities (QFEs) like the larger banks – must be registered. But registered FAs are minimally regulated. The only advice standard they face is a duty of care.

But to be able to provide ‘complex’ advice (covering more than 2 financial products), an ‘investment planning service’, or ‘financial planning’ advice a FA must also be authorised (AFA).

Becoming and remaining authorised requires compliance with a ‘client first’ code, documented advice – with support, and maintaining professional competency.

Nearly five years in, there are only 1800 AFAs in New Zealand, about 60 percent of whom work at QFEs. And perhaps because the AFA standards are not too different from what is required of CFP professionals, the QFEs don’t generally encourage their AFAs to seek CFP status. This, plus an aging adviser cohort, may help explain why we have only 350 CFP professionals here – about 15% fewer than five years ago.

So whilst well remunerated, professional financial advisers are thin on the ground. With one to every 2,500 people – or if QFE AFAs are excluded – one to 6,000; the world is a non QFE AFA’s oyster in New Zealand.