Executive Summary

When an advisor runs their own solo advisory firm, their capacity to meet with current and prospective clients is limited to the extent that they are also responsible for all of the non-client-facing tasks of running their firm. Which may not be a serious limitation when they are just starting out and don’t have a lot of clients to serve, but as the firm grows, they will eventually run out of time available for working with clients – at which point, it becomes necessary to decide whether to stay a solo firm (without taking on more clients) or to hire support staff to free up more time for the advisor/owner to prioritize client work and optimize advisor capacity.

Advisors who have never hired before may have little idea of what to expect once they do decide to hire. Will they be able to support themselves with the additional overhead cost of their employees? What type(s) of employee should they hire? Will they actually get to spend any more time working with clients, as was the original goal?

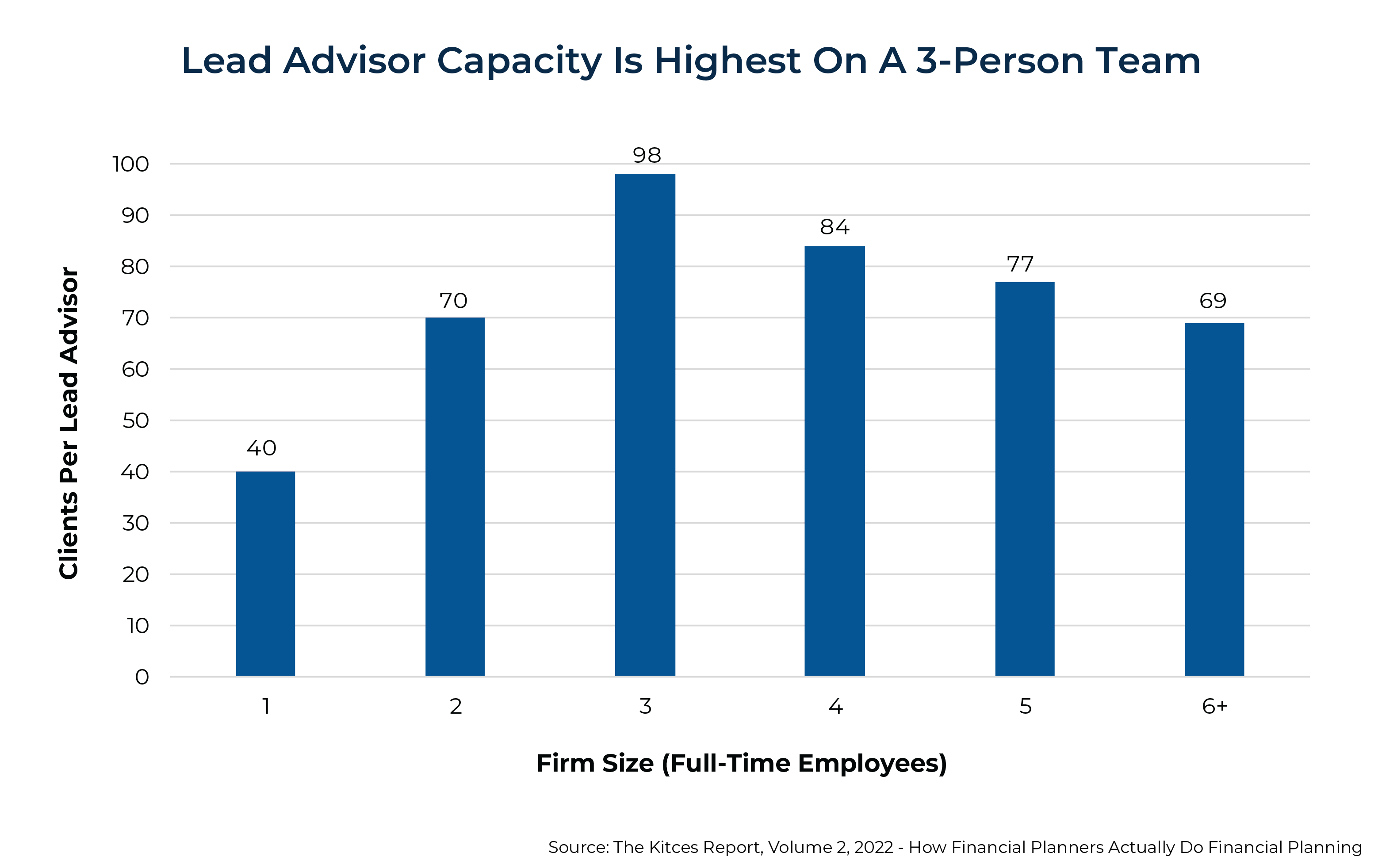

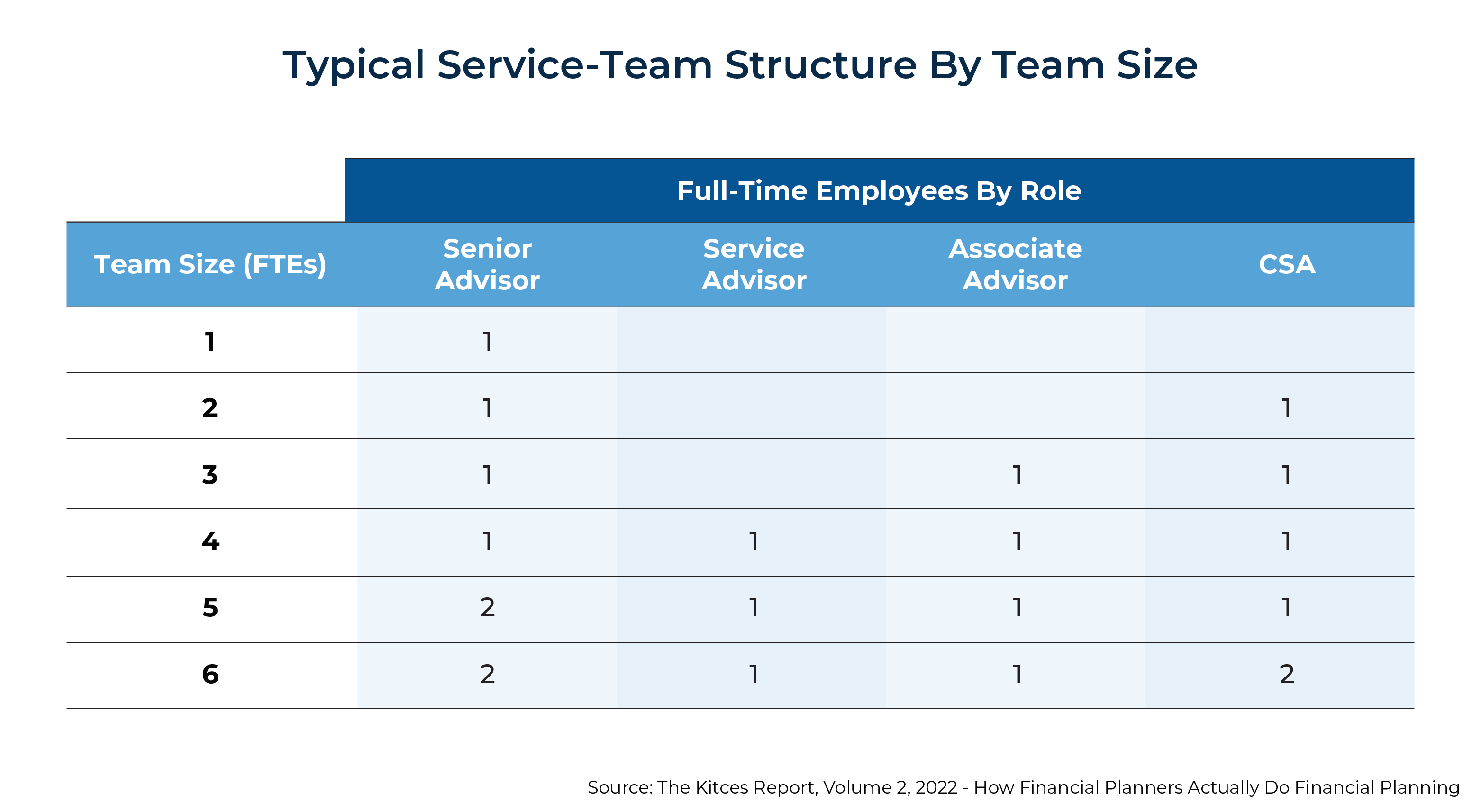

Data from the 2022 Kitces Research Study on “How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning” provide some answers about what advisors can expect when going beyond a solo practice, shedding light on the impact that hiring has on advisor capacity. According to the study, solo firms with no employees had a median of just 40 clients per advisor, while 2-person firms had 70, and 3-person firms had 96, as the advisor leverages themselves and their time by building a support team of a Client Service Associate (CSA) and an Associate Advisor around them. Notably, though, at 4 employees and beyond, the number of clients per lead advisor tends to go down from its peak of 96, as teams at this size typically begin to add another lead advisor. In other words, a 3-person team really seems to be the sweet spot where advisors are able to maximize their capacity, meaning that solo owners who want to hire 1 employee to focus more on client-facing work perhaps really ought to consider hiring 2 instead – while those who are already on a 3-person team might want to think twice about going much farther beyond that!

Additionally, while many firms tend to first hire a Client Service Associate (CSA) as their first hire and add an Associate Advisor later as their second, the actual job description of an initial hire really depends on what types of tasks the advisor wants and needs to delegate first – which in practice tend to be some of the advisor’s least-favorite work (hence why the CSA’s paperwork-heavy duty often gets delegated first), but can mean that an initial hire can really be more of a hybrid role, growing into one that is more specialized as the advisor delegates more and more tasks as the firm continues to grow. And to some extent, the needs of the first hire will vary depending on what the advisor themselves is good at doing (e.g., advisors who struggle with paperwork may hire a CSA first, while those who excel at building systems and process may hire the Associate Advisor first, and later a CSA to leverage them both).

Ultimately, what’s most important for advisors looking to hire is to have a plan for growth since the significant overhead cost of employees can greatly erode a firm’s profits until it can add enough revenue to make up the difference. Fortunately, what the data show is that hiring can open the door for this growth by boosting the advisor’s capacity and (as is presumably the primary goal) giving them the time to meet and bring in new clients!

Many advisory firms start out as solo practices, with a single advisor/owner handling both client-related duties (like meeting with clients and building and analyzing financial planning recommendations) and the responsibilities of running the advisory firm (like marketing, accounting, compliance, and other administrative tasks), as well as bringing in new clients to further grow the business. This setup has its benefits: The solo advisor has complete control over how they serve their clients and gets to keep all of the firm’s profits with minimal overhead expenses.

However, the greater scope of the duties involved with running a solo advisory firm means that, compared with advisors on larger teams, solo advisors have a relatively low capacity for the amount of client work they can take on. In other words, the tradeoff for solo advisors in being able to serve clients the way they want to is that they can’t serve as many clients as they would otherwise be able to. They need to balance their time serving clients with the other tasks they retain in working on and in the business.

With solo advisors, there’s often a desire to outsource or automate as many tasks as possible that aren’t directly related to client meetings in order to maximize the amount of time spent meeting with and advising clients. Which makes sense, because not only is that client ‘face time’ some of the most valuable time that advisors can spend in terms of generating revenue for the firm, but it’s also the part of the work that advisors tend to enjoy the most since the opportunity to work with clients and help them resolve their financial problems is the reason why many advisors get into the business in the first place.

But while advisors can streamline some processes with technology (e.g., using a TAMP to automate the process of investment management) and outsource other processes to third parties (like hiring a compliance consultant to take on many of the firm’s compliance tasks, or outsourcing bookkeeping to a specialist), it still isn’t possible to offload every ancillary task.

Furthermore, the sheer number of different types of duties and processes that a solo advisor is responsible for – even if the amount of time spent on each is reduced to its absolute minimum – can create enough mental noise (an inevitable byproduct of switching between tasks, or outsourcers that must be overseen, throughout the day) to reduce the level of focus they can achieve on client-facing work (and therefore the number of clients they can serve effectively).

Hiring Support Staff Is About Serving More Clients In The Same Amount Of Time

To address the limits of their capacity, solo advisors often look to hire support staff, with the thinking that having internal support (as opposed to outsourced support, which the solo advisor is still ultimately responsible for implementing and managing) for their non-client-facing work will allow the advisor to spend more time on the client work they enjoy most.

However, the expectation of being able to leverage support staff into more time spent in front of clients is often misguided. As previous Kitces Research on advisor productivity found, experienced solo advisors, both with and without support staff, on average spend fewer hours per week directly meeting with clients than the ‘typical’ financial advisor, and while hiring support staff does tend to increase solo advisors’ client-facing time somewhat, the responsibilities of running a practice (which, for advisors with support staff, also includes time spent on supervising and managing that staff) inevitably leave solo advisors with less time for meeting with clients than advisors who are able to leverage a larger firm’s resources. (And in fact, solo advisors with support staff on average work more weekly hours in total than their unsupported peers, since the work hours that they save by delegating tasks to their employees tend to be more than offset by the added responsibilities of managing those employees.)

For solo advisors who want to maximize their time spent on meeting with clients, then, the best path forward likely isn’t to hire staff; it’s to not be a solo advisor. That may sound flippant, but if maximizing client meeting time really is the overarching goal, it could actually be worth considering joining an larger firm where, with the advisor not responsible for the administrative and management duties of running a solo practice, they would be able to more fully focus their time on working with clients.

Because the reality is that running an advisory firm – separate from the role of advising clients – is a job in and of itself, and one that doesn’t go away with the addition of more employees as long as the owner/advisor is still the one running the show. To the extent that solo advisors can offload their existing non-client work onto support staff, it’s often just replaced with new kinds of tasks associated with managing employees and running a bigger firm.

But assuming a solo advisor does want to continue running their own firm, what is the point of hiring support staff if it won’t lead to significantly more time spent with clients? Every firm owner has their own reasons, but Kitces Research data suggests hiring support staff, while not necessarily allowing advisors to spend more of their working hours with clients, does allow advisors to serve more clients overall. Previously unpublished data from Kitces’ 2022 Advisor Productivity study found that solo advisors with support staff served nearly 3x more clients per advisor than solo firms with no support staff (93 for supported solos versus 36 for pure solos with no support), despite spending only about 1.5x more time meeting with clients per week (6 hours versus 4 hours).

The data suggests that hiring staff leads advisors to spend less time per client, which gives them the capacity to serve more clients in roughly the same amount of time. Although notably, there isn’t necessarily any less work being done for the clients: As non-meeting-related tasks are shifted from the lead advisor to their support staff, the advisor’s time per client goes down but the team’s time per client tends to stay the same or even increase. But because the addition of support staff creates more team members to share the workload for each client, even though the advisor doesn’t necessarily have more hours in the week to meet with clients, they’re still able to meet with more clients in the same number of hours.

In other words, for solo advisors, the decision to hire staff isn’t likely to result in more time meeting with clients; however, it can allow the advisor to serve more clients overall. (And, of course, hiring employees means that the advisor will likely need to bring in more clients – and serve them efficiently – in order to pay their employees and have take-home profits left over for themselves.) When the decision to hire is driven by the desire to grow the firm’s client base and revenue, as shown below, it’s more likely that the advisor will be happy with their decision in the long run.

Why A 3-Person Team Maximizes Advisor Productivity

Additional data from the 2022 Kitces Research study on “How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning” suggests that advisors get a substantial capacity boost not just from their first employee but from their first 2 full-time hires. Compared to 1-person advisory teams (where the advisor is presumably the single employee), which have a median of 40 clients per advisor, the number of clients per advisor increases to 70 for 2-person teams and jumps further to 98 for 3-person teams. (Astute readers will note the small variation between these numbers and the solo firm versus supported solo statistics noted earlier, which is likely due to slight differences in how advisors self-identified in the research survey, e.g., an advisor for an independent broker-dealer may be the only person on their service team but might not have identified as a ‘solo advisor’ for purposes of the research survey. But the differences are small enough that they can be ignored when looking at the broader trends of what happens when more employees are added alongside a single advisor.)

Notably, 3-person teams generally include only 1 ‘lead’ advisor (the advisor running the firm, plus a Client Service Associate and an Associate Advisor), which means that the denominator in the ‘clients per advisor’ number remains at 1 – and so the more than doubling of client capacity in going from a 1- to a 3-person team consists entirely of additional clients served by the single firm owner/advisor.

As teams grow to 4 members and beyond, they typically begin to include additional lead advisors, reducing client-per-advisor rates by increasing the denominator in the equation (and likely further limiting the original owner/advisor’s capacity due to the increased management responsibilities of adding additional advisors, who may eventually require their own support staff).

The upshot of this data is that while hiring 1 staff member can help an advisor boost their client capacity versus what they were capable of as a solo advisor, it isn’t until they hire the second staff member that the advisor can maximize their potential for productivity.

One possible reason for this is that, as the firm accumulates new clients, those clients create additional work in the areas that the advisor didn’t hire for. For example, if an advisor hires a Client Service Associate (CSA) to handle client service tasks – but doesn’t hire an associate advisor to support financial planning analysis – then any new clients that the firm brings on will result in new client service tasks (which can be absorbed by the CSA) and new financial planning analysis tasks (which would need to be covered by the advisor).

An advisor who only hires a CSA, then, might gain some time from delegating away their client service work – only to find it taken up instead by financial planning-related tasks like plan preparation and analysis, which limits the time they can devote to client-facing work. The more clients the firm adds, the more the need will increase to make a second hire in the form of an associate advisor to cover the non-client tasks that aren’t supported by the CSA.

When the advisor hires support staff for both roles – a CSA and an associate advisor – those 2 employees are able to absorb the work created as new clients are brought on board, allowing to advisor to focus more on their core responsibilities of advising clients, bringing in new business, and managing the business of the firm. Hence, the 3-person team is the sweet spot where the advisor has enough support to focus their time and energy around client-facing work to maximize the number of clients they can serve – but the firm’s client base isn’t so big yet that it needs to hire more advisors to serve them effectively.

Revenue And Take-Home Income With A 3-Person Team

For many advisors, the ability to maximize client capacity has its own intrinsic benefits. The advisor can help the greatest number of families with their advice and create many lasting client relationships that often have a deeper meaning than ‘just’ business relationships. However, as business owners, the main upside of growing the firm’s client base is the associated increase in revenue and, ultimately, take-home income.

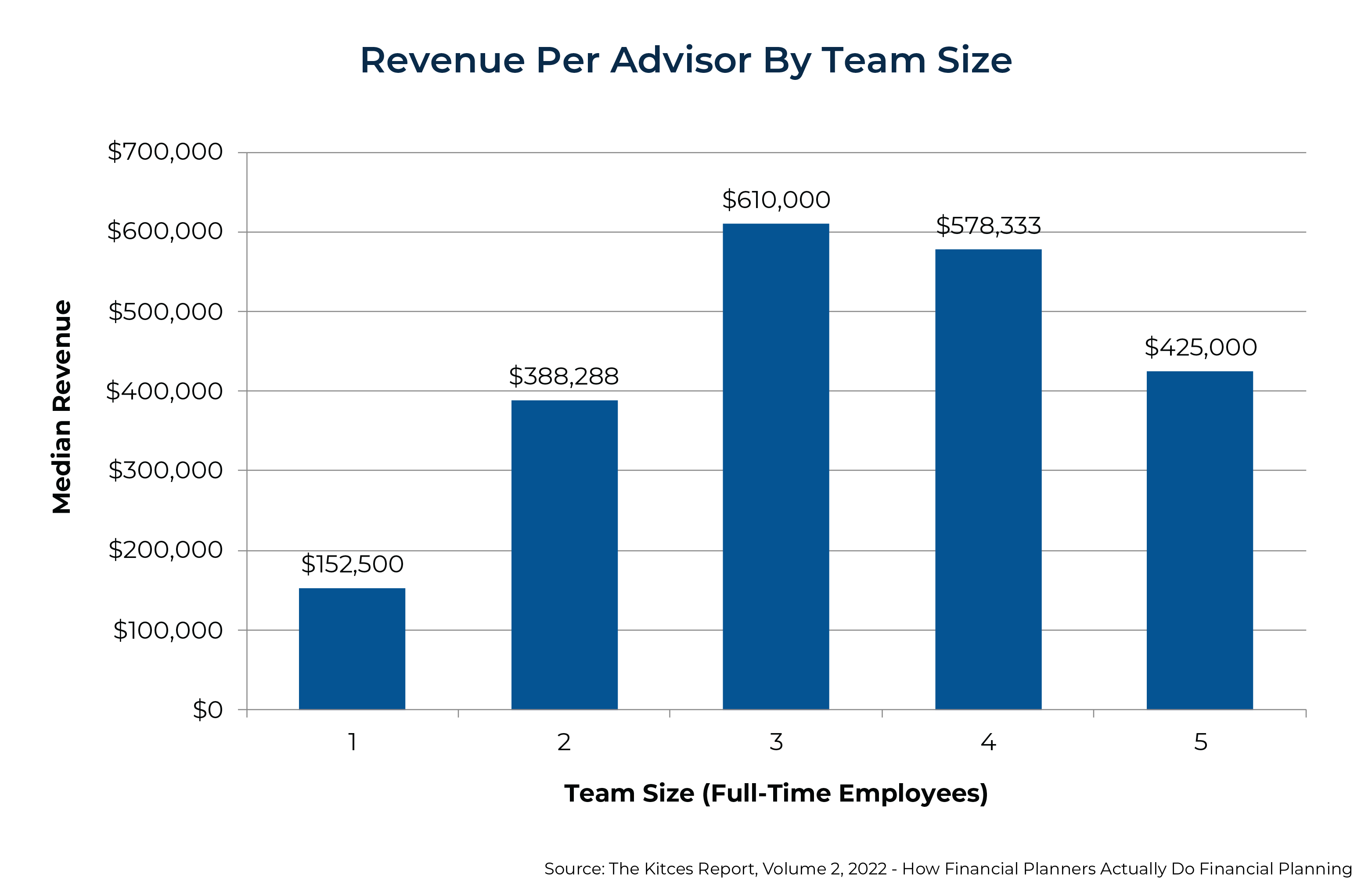

As would be expected, the 3-person team, which features the highest number of clients per advisor among teams with 1 to 5 full-time employees, also results in the highest amount of revenue per advisor (a measure of overall advisor productivity). Data from the 2022 Kitces Research study on “How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning” shows that advisors on 3-person teams have 4x the revenue ($610,000 versus $152,500) of solo advisory firms and 57% more ($610,000 versus $388,288) than advisors on 2-person teams. And just as the number of clients per advisor starts to drop off after peaking at 3 total team members, revenue per advisor also declines after the service team crosses over to 4 team members and beyond.

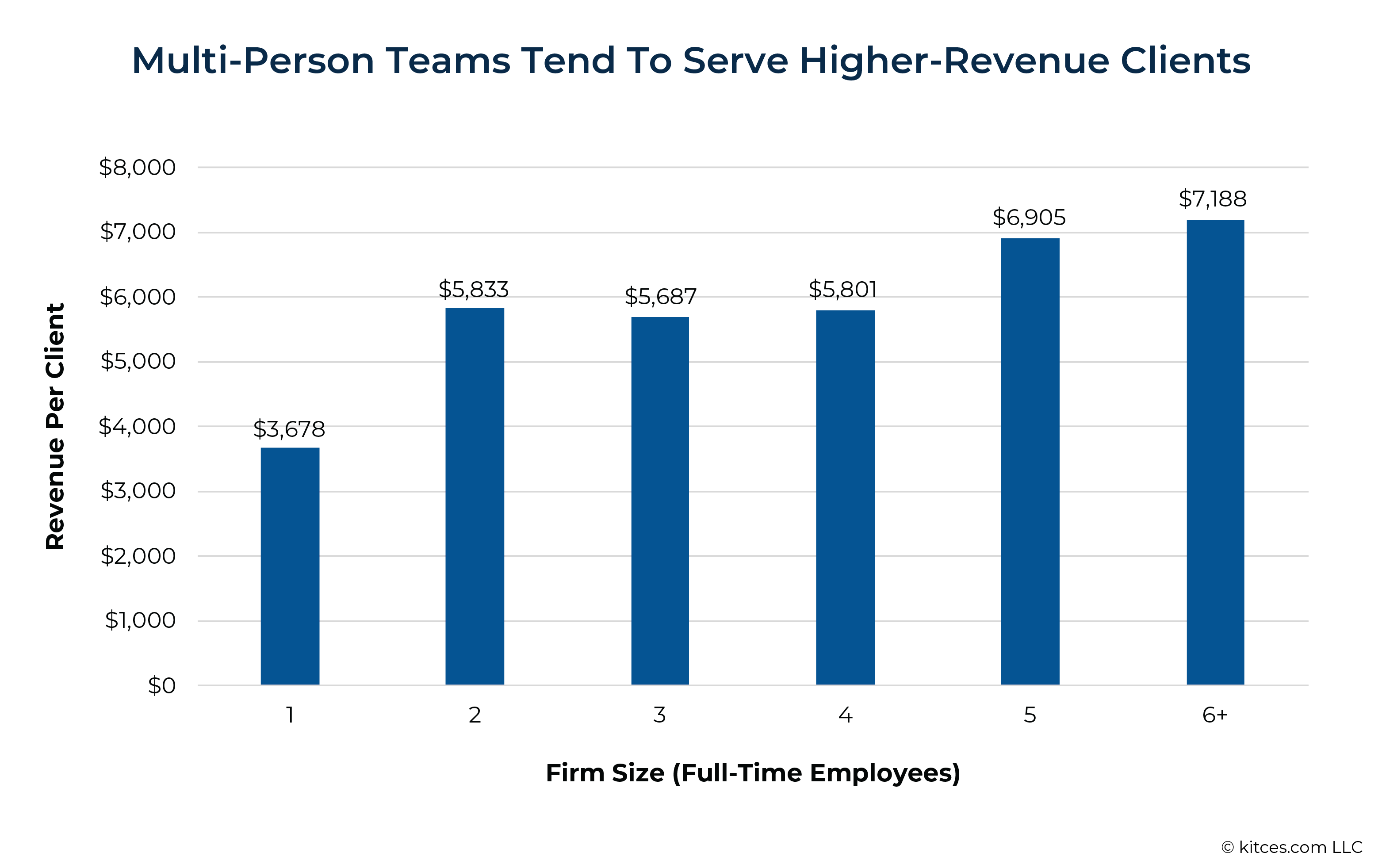

The boost in revenue in going from a 1-person to a 3-person team comes not only from serving more total clients but also from getting more revenue per client. In the Kitces Research study, firms with 2–4 full-time employees earned between $5,687 and $5,833 per client, versus $3,678 for firms with just 1 full-time employee. The jump that comes immediately with hiring a second employee, as shown in the chart below, suggests that the decision to hire can often come with a conscious choice to serve higher-revenue clients (who otherwise have more complexity, take more time, and are more difficult for the advisor to serve well if they don’t have support). Which makes sense: Immediately after hiring a full-time employee – before enough clients have been brought on board to make up the cost of paying them – there’s pressure to generate revenue to fill the hole in the firm’s income statement. Raising fees, whether that’s in the form of an across-the-board fee increase or simply an increased focus on bringing in higher-revenue clients, can be the fastest way to make up the difference.

How does the additional revenue created by hiring employees compare to the cost of the employees themselves? According to the annual InvestmentNews Adviser Benchmarking Study, the median total compensation amounts for a CSA and an associate advisor in 2021, respectively, were $58,500 and $71,087. Adding these together (plus an extra 20% to account for payroll taxes and benefits) would make the total cost of hiring both employees at the median salary ($58,500 + $71,087) × 120% = $155,504.

The difference in total revenue between the median 3-person team and a solo advisor, as shown above, is $610,000 – $152,500 = $457,500, from which the advisor paying an additional $155,504 in employee costs still results in a take-home pay that is more than $300,000 higher (nearly 3X what the unsupported solo advisor was making!). In other words, the additional revenue made possible by hiring employees would presumably make up for the cost of the employees, with room for added profit on top. (Though it would take time for the advisor to build up their capacity to eventually reach their peak revenue-generating ability – meaning that the firm would still need to be profitable enough before hiring employees to support the cost of paying them until the advisor could bring in enough new clients and revenue to make up the difference).

Creating The Roadmap For A 3-Person Team

Lying beyond the decision of whether or not to hire support staff is the question of whom to hire (as well as what order in which to hire them). Since the goal in hiring is generally growth in both the number of clients and the amount of revenue, it makes sense to hire the type of staff that will best support the advisor’s ability to bring in and serve new clients.

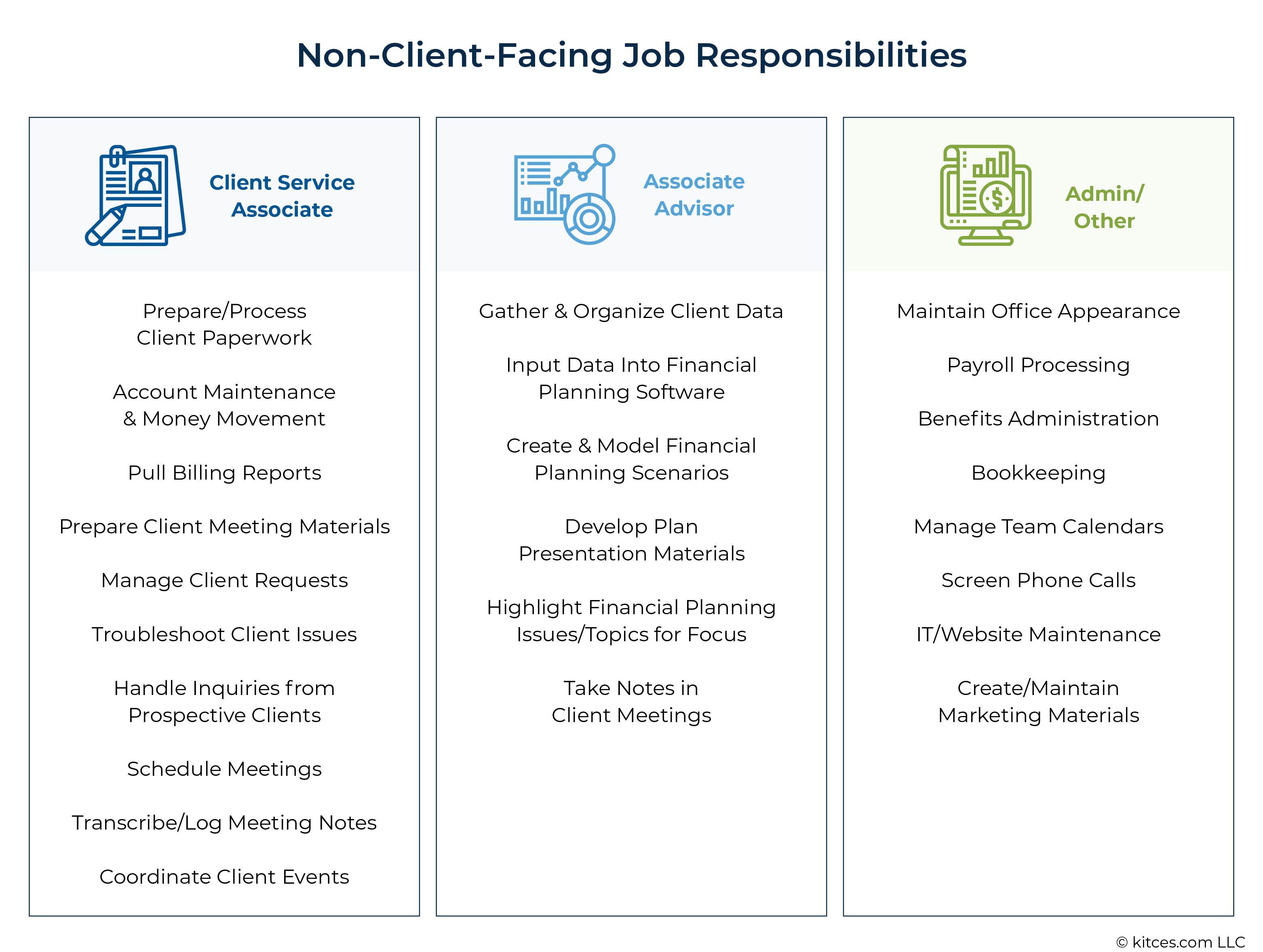

The 2 most common support roles for financial advisors are:

- A Client Service Associate/Administrator (CSA) who supports advice implementation (e.g., account opening and money movement), handles client inquiries, and often performs other administrative duties like meeting scheduling; and

- An Associate Advisor who handles financial planning and analysis tasks and sometimes meets with clients (though typically not as a ‘lead’ advisor with their own clients) and who might also be called a ‘Paraplanner’ depending on the exact nature of the role. (Notably, within Kitces Research, the title “Service Advisor” is typically reserved for those who have primary responsibility to lead their own client relationships, while Associate Advisors focus on supporting a Lead Advisor with ‘their’ clients.)

The 2022 Kitces Research study data showed that 2-person teams overwhelmingly consisted of the advisor plus a CSA, while 3-person teams most often included the lead advisor, a CSA, and an Associate Advisor. In other words, advisors tend to hire CSAs as their second team member, with an associate advisor most often being the third (and more lead or service advisors with primary client responsibilities following after that).

The intuitive reason for hiring a CSA first is that they are generally paid less than an associate (or service) advisor and thus represent a smaller hit to the firm owner’s bottom line: As mentioned above, according to the 2022 InvestmentNews Benchmarking Study, the median CSA earned $58,500 in total compensation, while the median “support” advisor (equivalent to the associate advisor for these purposes) earned $71,087. Additionally, the work that a CSA can take over for the advisor represents the greatest ‘boost’ in value to the advisor, replacing less-specialized or administrative tasks with time spent on deeper planning, more relationship building, or both. Not to mention that in practice, advisors are often much better at finding and serving clients than building systems and processes, which an administrative team member can then help establish when they come on board.

However, while the short answer is that it often makes sense for solo advisors to hire a CSA before bringing on an associate advisor, the longer answer for advisors who want the most growth in clients and revenue is that they will eventually need to hire for both roles in order to stabilize their workload and maximize their capacity. And the sequence is more about where the advisor’s own weak points are – those who excel at technology and systems and process themselves may hire an Associate Advisor first and then a CSA to support them both (because administrative work isn’t a pain point thanks to the advisor’s own ability to automate for themselves), while those who are not as strong at systems and process tend to hire the CSA role first.

By either path, though, the data from the Kitces Research study suggests the following story:

- For solo advisors, hiring employees creates more client capacity by adding team members to share the load and increasing the aggregate time available for client service.

- The gains in capacity allow the firm – once it has actually brought on enough new clients to fill its additional capacity – to increase its revenue by significantly more than the cost of the employees.

- For the lead advisor, productivity in terms of capacity and revenue generation tend to reach their peak with a 3-person advisory team – and begin to decline on a per-advisor basis as the team grows to 4 members and beyond, as the complexities and management duties of running the firm compound with the additional employees.

No 2 advisory firm owners are 100% alike in deciding when and whom to hire, but the data presented above – along with previous research on when advisors tend to hit their personal capacity walls and need to hire support staff to grow further – can help to sketch out a hiring roadmap for firm owners to chart their own business’s growth path, starting from a solo practice and growing to a 3-person team.

At a high level, the most common roadmap looks like the following:

- First hire: Client Service Associate at 30–40 clients / $200,000–$300,000 of revenue

- Second hire: Associate Advisor at 60–70 clients / $400,000–$500,000 of revenue

Notably, in practice advisors tend to face a capacity pain point based on the number of clients, but the financial capacity to afford staff is driven by revenue. As a result, advisors with “smaller” clients can face a challenging point where they have “too many” clients to keep growing, but too little revenue to hire (or at least, must take a bigger personal step backwards in take-home pay to make the hiring investment). As a result, while beyond the scope of this article, sometimes the best thing an advisor can do is not to hire when they reach capacity, but first raise their fees to be able to afford staff support (and if a few clients leave, the advisor may still have more revenue from fewer clients, bringing them capacity to then grow further).

More broadly, though, while the Kitces Research data may provide helpful guideposts on when and whom to hire, it also leaves a lot of blank space for advisors to determine how hiring will best support their own success. What will the new hire(s) do? What will the advisor’s day look like when they’re no longer a solo advisor? What (if anything) lies beyond the 3-person advisory team, and how will the other team members’ roles evolve over time? These are all crucial questions for advisors to answer as they determine their paths as advisors and firm owners.

Deciding On A Job Description

One of the advantages of being a firm owner is the ability to design employee roles that suit the owner’s needs, and part of the process of making a first (and eventually second) hire is deciding which tasks would be best to offload to free up the advisor’s time for growing the business.

Consider this starting list of the many non-client-facing tasks that solo advisors are responsible for, sorted by the types of employees who, if the advisor were to hire someone, would generally take them over:

While this list might reflect the standard job descriptions of these roles as they currently exist at many advisory firms, there’s nothing that says a new employee's job description needs to fall entirely within one category or the other. Particularly at small firms with 1 or 2 employees, owners may decide to mix and match employees’ tasks just to cover the work that needs to be done before settling into more specialized roles as the firm matures. And often, the reality is that at the point when the advisor needs to hire a first employee, there might not yet be enough work under the domain of just 1 role to justify a full-time position, so a first hire may be more of a hybrid role while the advisor works to fill up their extra capacity.

In that vein, an advisor might (for example) hire a first employee who is primarily a CSA but perhaps covers some admin tasks like calendar management and marketing support as well. More rarely (but not unheard of), they may hire an associate advisor who also covers some CSA tasks (recognizing that this may literally be “overpaying” for the cost of staff to execute on those tasks). Or the advisor may simply decide to hire someone in a single role as a part-time position to start out until enough work builds up as the firm adds clients to grow up to full-time. (Or alternatively, to use an outsourced virtual assistant/admin service for part-time help until they’re ready to hire into a full-time role for themselves.)

In any case, what’s important is to map out the job description in advance of hiring for the role. Clarifying the specific types of tasks that potential new hires will be handling ensures that their expectations match the actual makeup of the role. And if the job really does end up being a sort of catchall for all of the tasks the advisor wants to delegate – that’s OK too, but if that’s the case, that should be made clear when hiring for the role to avoid potential confusion and frustration if the role has no clear boundaries.

Delegating Tasks As The Firm Grows

As shown by the Kitces Research data, the main effect of going from a solo advisory firm to a 2- or 3-person team is creating room for growth. The support provided by an initial hire frees up extra capacity for the advisor, who can focus on bringing in more clients and more revenue to make up for (and hopefully soon exceed) the cost of the employee – which then allows the advisor to hire another employee to expand even more capacity for new clients and revenue.

But the key to maintaining this growth is in making sure that the advisor’s capacity actually remains open for bringing in and advising new clients. If the advisor hires an employee but retains so much non-client-facing work that they can’t devote the time needed for their existing client and business development duties, then there won’t be room to grow the business even to the point of making up for the cost of the employee. And as the advisor does bring in new clients (who will each incrementally add to the advisor’s workload), it’s equally important to continue to manage capacity so there remains room for new growth.

Which ultimately means that advisors may have an initial set of tasks that they offload right away when they initially hire an employee, and then a second set of tasks that they gradually delegate to the employee over time as the firm brings in new clients in order to keep the advisor’s capacity open. Similar to the Entrepreneurial Operating System (EOS)’s “Delegate and Elevate” technique, advisors can periodically inventory their day-to-day tasks and categorize them as those that are essential/enjoyable for them and those that they wish to delegate. When they feel they are reaching their capacity, they can pass off some of the delegable tasks to open up space to continue growing the firm.

Obviously, the most preferable tasks for the advisor to delegate would be the ones in the bottom-right square that are least essential to their role, and least enjoyable to them personally. From there, they face a tradeoff between offloading tasks that are enjoyable to them but nonessential to their role (and thus relatively easy to delegate away), or those that are currently essential to their role but less enjoyable to them (and would require an additional time investment in training to allow them to be delegated – for example, gathering and entering data into financial planning software might be an essential task for the advisor until they can train a new hire on their process for doing so). Ultimately, the goal is to have as many tasks in the upper-left (Essential/Enjoyable) square as possible.

When both the advisor and employee are near their respective capacities, then the employee can do a similar inventory themselves – which could lead to outsourcing some of the tasks that the employee finds less enjoyable or essential to their role or perhaps to deciding that it’s time to hire a second employee.

What Lies Beyond The 3-Person Team

Building a 3-person advisory team can be the ideal strategy for the type of solo advisor who decides to hire in order to increase their ability to serve more clients. As the Kitces Research data shows, client capacity more than doubles between the median solo and 3-person teams as the advisor is able to share the client work among team members, which supports the firm’s growth by allowing the advisor to bring in new clients.

But there’s still a capacity limit that advisors will reach even with the most efficient and well-run teams, and research and experience have shown that advisors tend to max out on their ability to maintain client relationships somewhere between 75 and 125 clients (with the exact number depending on many factors including the depth and engagement of the client relationships, the advisor’s own personality type, and the number of relationships the advisor maintains outside of their work).

Which means that, at some point, having hired and grown the firm to reach the limits of their personal capacity, advisors running a 3-person team will eventually reach their own capacity crossroads where they will need to decide whether to 1) stop growing and only add new clients when an existing client leaves, or 2) continue to build and grow the firm by adding a new lead advisor to take on client relationships themselves (such that the founder/owner may not interact with those clients at all). Both options represent major changes for the advisor: Option 1 shifts their focus from a constant-growth mode to one where they pull back and refocus on building and maintaining client relationships (and maximizing profitability), and Option 2 necessarily adds more responsibilities to the advisor’s plate – since they will now need to bring in a second lead advisor to bring in more business, along with potentially more support staff, significantly expanding the advisor/owner’s management role – which ultimately reduces their client capacity as they work to manage the business as a whole.

It isn’t necessary (or practical) to have this decision mapped out at the point of hiring the first employee. But it’s worth having in the back of one’s mind while talking with potential new hires, given that the first 1 or 2 employees may have a significant role in shaping the business over time – and that being able to offer a potential career path that aligns with a new employee’s goals can lead to the employee being on board with supporting the advisor’s vision for their (and the firm’s) growth.

Solo advisory firms, by definition, start with individuals, and individuals have their own ideas, goals, and needs… meaning that there necessarily can’t be one single road map for turning a solo firm into a 3-person team.

But it still helps to have an idea of what to expect before, during, and after hiring in order to better predict (and address) some of the issues and challenges that arise. Data can help us create some of those expectations, and what the data show (in the form of Kitces Research studies on How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning and What Actually Contributes To Advisor Wellbeing) is that hiring not only creates the capacity to serve more clients but also makes it necessary to do so in order to support the higher overhead costs associated with more employees.

Ultimately, the takeaway is that solo advisors who decide to hire in order to spend more time with clients will truly need to do so in order to sustain their growth – but fortunately, it appears that hiring does actually open up that capacity!