Executive Summary

In today’s highly competitive job market, many industries have more openings than there are qualified employees to fill them. Which means that many workers are finding that they have the luxury of being able to choose amongst a number of potential employers. And in an effort to recruit (and retain!) top talent, it’s important for employers to not only offer competitive pay but a compelling benefits package as well, including, in particular, a generous retirement plan. In many cases, a 401(k) plan is the retirement plan of choice, as it offers substantial contribution limits, allows employees to defer taxes on income contributed to the plan and gives employers the option to offer profit sharing and matching contributions as well (that they can deduct themselves from their business income).

The caveat, however, is that many employers (especially small business owners) lack the knowledge and time it takes to properly administer a retirement plan as a plan sponsor, which is important not only to prevent penalties and fines but also to maintain a plan’s qualified tax status. And given that there were over 83,000 ERISA-related lawsuits in the past decade alone, liability risk when offering a 401(k) plan is understandably a significant concern, as plan sponsors have a fiduciary responsibility to act prudently and in the best interest of the plan participants (i.e., the employees enrolled in the plan). This entails offering a diverse mix of investment options, ensuring that the plan expenses are reasonable, and following the documents as written for the plan.

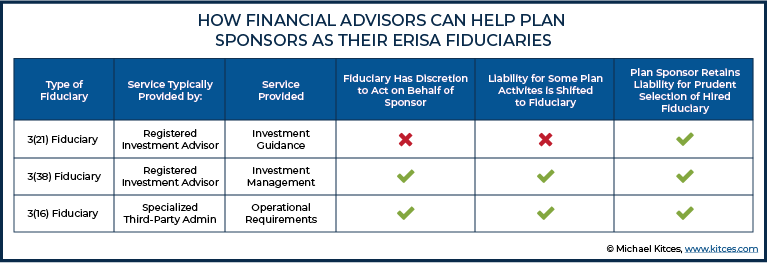

The good news, though, is that advisors can help employers manage these responsibilities by providing various fiduciary services. More specifically, advisors may provide plan sponsors with investment-related services by serving as either an ERISA “3(21) Fiduciary” or a “3(38) Fiduciary” (named after the sections of ERISA that define a fiduciary). In addition, advisors can help plan sponsors find a reliable “3(16) Fiduciary” to provide administrative and operational support.

An advisor offering 3(21) Fiduciary services, for instance, provides a plan sponsor with investment recommendations (i.e., which funds should be included in the plan lineup), though the plan sponsor still ultimately makes all final decisions and is the party responsible for actually taking action. Thus, while a 3(21) Fiduciary’s advice should, in theory, help a plan sponsor to reduce their risk (as the 3(21) Fiduciary should have more investment experience and knowledge than the plan sponsor), the plan sponsor still retains liability for investment-related decisions. By contrast, a 3(38) Fiduciary advisor not only recommends investment options but serves as an investment manager, approving and implementing the recommendations made into the plan. When engaged as a 3(38) Fiduciary, the liability for investment management is largely shifted to the advisor and away from the plan sponsor (though the sponsor can't fully delegate the fiduciary obligation, and remains liable for prudently selecting the 3(38) Fiduciary in the first place). Finally, advisors can educate plan sponsors on the value of a 3(16) Fiduciary, who provides plan administration services. Notably, the 3(16) Fiduciary acts on behalf of the plan sponsor with respect to administrative functions and also assumes the liability for such functions. It’s important to note that both 3(21) and 3(38) Fiduciaries are generally provided by Registered Investment Advisers (but not by broker/dealers), while 3(16) Fiduciaries are typically specialized “Third Party Administrators”, and are not generally investment professionals.

Ultimately, the key point is that advisors have an opportunity to provide employers options to help them manage not just their retirement plans but their fiduciary liability in making the plan available to their employees, effectively shifting much (but not all) of the fiduciary responsibility (as well as liability) from the plan sponsor over to the Fiduciary advisor themselves. Regardless of how administrative or investment liability may be shared or shifted, though, the plan sponsor will always have the liability of due diligence in vetting and selecting appropriate Fiduciaries for the plan. Nonetheless, depending on what level of involvement the employer wants to have in their retirement plan, advisors can provide one or more types of fiduciary services to provide for the plan sponsor’s needs to balance limiting their liability, while providing the retirement plan they want to offer that helps them attract and retain top talent!

Finding and keeping good employees is tough and has always been tough, and in today’s market, it might be more challenging than ever before. Specifically, as recently as August 2019, there were still nearly 1.4 million more job openings than there were unemployed persons looking for work! In fact, some qualified job seekers have found so many opportunities that many employers are being ‘ghosted’ by individuals during the interview process or, in some cases, even after they’ve made a legitimate offer of employment!

In an effort to attract and retain talent, employers have increasingly sought to introduce all sorts of perks and ‘goodies’ into the employment benefits package, from paid maternity/paternity leave (which is standard in many other parts of the world, but still a differentiating perk in the United States) and on-site daycare, to flexible hours and paid sabbaticals. Of course, as employers continue to offer new and more exotic benefits, it turns other previously optional benefits into veritable ‘requirements’ to attract any sort of talent.

Accordingly, in today’s job market, 401(k) and/or other retirement plans are often just considered employee benefit ‘table stakes’, and if a business doesn’t at least offer its employees a retirement plan option, they are likely to miss out on many qualified candidates who might otherwise consider employment with that business. In fact, according to the 19th Annual TransAmerica Retirement Survey of Workers released earlier this year, some 86% of workers cited a 401(k) or similar plan as a “Very/Somewhat Important” benefit, while 81% “Strongly/Somewhat Agreed” that retirement benefits would be a “major factor” in deciding to accept a job offer.

401(k) Plans Involve Substantial Administrative Compliance Requirements And Liability

Given the potential benefits of offering a 401(k) or similar plan (not to mention meeting employee expectations), one might think of it as a ‘no-brainer’ for employers to offer such a benefit. But aside from the obvious costs associated with a 401(k) plan, there is a non-trivial administrative compliance burden that must be fulfilled, and potential liability exposure for employers who fail to comply… which in turn have become the two main reasons why employers shy away from offering such plans.

The administration of a 401(k) plan, for instance, can be rather time-consuming and complicated for employers that try to navigate the range of different types of plan features and benefits and fulfill all the ERISA requirements in administering the plan to their employees. In extreme cases, failure to properly administer a plan can jeopardize the qualified status of the plan, and thus, the ‘special’ tax treatment, associated with plan assets.

In addition, plan sponsors are responsible for selecting the available investment options for all plan participants (unless they make other arrangements to delegate the responsibility, as discussed below). And while plan participants generally retain the right and responsibility to allocate between those pre-selected options, properly evaluating the vast world of mutual funds and other eligible investment vehicles for inclusion in a 401(k) ‘lineup’ can be a daunting task, especially for those with limited investment experience of their own.

To make matters worse, plan sponsors are generally liable for both the investment decisions they make (i.e., the investment lineup they offer), as well as for properly administering the plan itself. And as if that wasn’t enough in and of itself, plan trustees (often the business owner or a Human Resources professional, and not a financial professional) – who, by definition, are fiduciaries of the plan – can be held personally liable for any errors and/or imprudent investments maintained by the plan.

Thankfully, for those plan sponsors and fiduciaries who want or need help in meeting these obligations, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) provides for several options where financial advisors can help them to both fulfill their fiduciary obligations and/or reduce their fiduciary liability, including:

- Hiring a 3(21) Fiduciary to provide investment recommendations,

- Hiring a 3(38) Fiduciary to outsource investment management, and

- Hiring a 3(16) Fiduciary to outsource plan administration.

Offering “3(21) Fiduciary” Services To Provide Investment Guidance

One way in which employers and plan trustees can attempt to reduce the liability associated with their 401(k) plan is to hire a financial advisor to serve as a “3(21) Fiduciary”. Under Section 3(21) of ERISA, someone is considered a fiduciary to an ERISA plan if:

“(i) [they] exercise any discretionary authority or discretionary control respecting management of such plan or exercises any authority or control respecting management or disposition of its assets, (ii) [they] render investment advice for a fee or other compensation, direct or indirect, with respect to any moneys or other property of such plan, or has any authority or responsibility to do so, or (iii) [they] have any discretionary authority or discretionary responsibility in the administration of such plan. Such term includes any person designated under section 405(c)(1)(B).” (emphasis added)

Note that Section 3(21) of ERISA describes any and all plan fiduciaries, which includes plan trustees, as well as 3(38) Fiduciaries and 3(16) Fiduciaries (both discussed in greater detail below). However, in the ‘real world’ when the term “3(21) Fiduciary” is used, it is generally meant to describe an individual who is providing investment advice to a plan (and, more precisely, to the plan trustees) for a fee (as emphasized above). This article uses the term in a similar manner.

Thus, while ‘anyone’ can technically be a 3(21) Fiduciary (as the trustees of plans often include business owners and/or Human Resources managers with no substantive investment or plan knowledge), those offering 3(21) Fiduciary services are generally providing counsel as a Registered Investment Adviser (provided by an Investment Advisory Representative of the firm). In fact, because Section 202(11) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, generally limits the offering of investment advice for compensation to a “Registered Investment Adviser” (whereas other professionals, such as brokers, dealers, and accountants, may only provide advice that is ‘solely incidental’ to their business/profession), those marketing themselves as 3(21) Fiduciaries generally must be affiliated with an RIA (or may be limited in their ability to actually provide such services).

The fees that a 3(21) Fiduciary charges must be reasonable, but such fees may be calculated in a variety of ways. For example, a 3(21) Fiduciary may charge by flat fee, or on a per-participant basis. The most common way to charge for such services, however, is as a percentage of plan assets. In such instances, as plan assets increase, the percentage (fee) being charged typically decreases.

3(21) Fiduciaries Recommend, But Do Not Have Discretion Or Act Unilaterally

One central characteristic of 3(21) Fiduciaries (in the context of investment advice) is that they ‘only’ provide advice recommendations about how they suggest the plan should act in choosing the investment options it provides to its participants. The plan sponsor retains the ‘final word’ on all decisions, and whether to actually take and implement those 3(21) advice recommendations, and remains responsible for taking action to implement those decisions.

Accordingly, activities of a 3(21) Fiduciary hired to provide investment advice are limited in scope (to the provision of that investment advice), but do generally include advising a plan sponsor on which funds should be selected for initial inclusion in the 401(k) lineup, ongoing monitoring and analysis of existing investment options, and recommending eliminations, additions, and/or other changes to an existing investment lineup. In addition, such fiduciaries may provide plan education to plan participants.

Example 1: Duff Beer Co. offers a 401(k) plan for its employees, but the plan trustees don’t feel entirely comfortable in their ability to select and monitor funds for inclusion in the plan investment lineup. As such, they hire Let’s Get Fiscal Financial Planning to provide ongoing 3(21) investment advice.

During a regular review of the plan’s funds in early 2019, Let’s Get Fiscal recommended to Duff Beer that it remove three funds from its current lineup, and add three new funds to replace them. Sid Duffman, one of the Duff Beer plan trustees, has a substantial amount of his own plan assets invested in one of the funds that was recommended for replacement by Let’s Get Fiscal. As such, he watches the fund closely and truly believes that it is a solid investment choice. He is convinced that keeping it as part of the plan lineup is in the best interest of the plan participants.

Thus, Sid Duffman ultimately decides to replace two of the three funds recommended for replacement by Let’s Get Fiscal, but will leave the third fund alone for now. Furthermore, Sid Duffman – the trustee, and not the 3(21) Fiduciary – must take action to actually facilitate the investment change.

Plan Sponsors Retain Investment Liability In 3(21) Fiduciary Engagements

Since plan sponsors remain ultimately responsible for the selection and monitoring of investments when engaged with a 3(21) Fiduciary, it’s only logical that they retain liability for those decisions. Of course, a 3(21) Fiduciary is also a fiduciary of the plan since they are providing advice to the plan (i.e., they are a co-fiduciary), and thus, they too have liability (as any RIA would have for the investment recommendations it makes to a client). That liability, however, is in addition to the liability of the plan sponsor and is not created by shifting liability away from the plan sponsor to the 3(21) Fiduciary.

Ultimately, a 3(21) Fiduciary’s ability to help a plan sponsor reduce their investment liability is more about helping the sponsor make good decisions so that participants remain confident that the sponsor is operating the plan in accordance with their best interests in mind, and less about actually removing the legal burden of the plan sponsor. Specifically, the 3(21) Fiduciary provides expertise to the plan sponsor so they can competently perform the investment functions required of them, that they would otherwise find difficult to do on their own and without guidance.

In essence, offering 3(21) Fiduciary services helps plan sponsors handle their fiduciary risk by actually making good plan decisions, as opposed to shifting their fiduciary risk away. Thus, if a participant disagrees with the investment decisions of the sponsor and believes that they have not met their fiduciary duty, and sues the sponsor and successfully proves the point, the sponsor remains liable to the participant. But by adding a 3(21) Fiduciary ‘into the mix’, a plan sponsor can potentially reduce, and hopefully even eliminate this possibility in the first place by actually making better investment decisions and offering a better investment lineup (or, in a worst-case scenario, give themselves a better defense by having the 3(21) Fiduciary’s analyses and recommendations to substantiate why the investment decision was made).

Example 2: Continuing with our previous example, Sid Duffman ultimately decided, against Let’s Get Fiscal Financial Planning’s (the 3(21) Fiduciary) advice, to keep a fund recommended for replacement. Ultimately, this proved to be a poor choice, as the fund was both more expensive than its peers, and underperformed for a sustained period of time.

As such, a lawsuit has recently been filed against the plan for failing to meet its fiduciary obligations in monitoring that fund. The plan, as well as the trustees (including Sid Duffman), remain fully liable for that decision.

The 3(21) Fiduciary could also be named in such a suit (hey, it’s America… anyone can be sued for anything), but given the fact that they provided prudent advice, and that the plan sponsor retains the ultimate liability for investment decisions (and they chose to ignore the 3(21) Fiduciary’s advice), they would likely be insulated from any liability that might ultimately arise.

Offering 3(38) Fiduciary Services To Provide Investment Management For Qualified Plan Sponsors

While a 3(21) Fiduciary may give some plan sponsors enough confidence to act in a manner that is sufficient to meet their fiduciary obligations, some plan sponsors may wish to further remove themselves from the responsibility of actually doing the work of investment selection and monitoring (and the liability that entails). In such cases, plans may wish to consider engaging the services of a “3(38) Fiduciary”, also known as an “Investment Manager”, who can help accomplish both.

Per Section 3(38) of ERISA, an “Investment Manager” is someone other than an already named fiduciary (i.e., the plan trustees) who:

- “Has the power to manage, acquire, or dispose of any asset of a plan”,

- Is a registered investment adviser, bank, or insurance company, and

- “Has acknowledged in writing that he is a fiduciary with respect to the plan.”

Thus, the language of ERISA prohibits broker/dealers from acting as 3(38) Fiduciaries, as they do not meet the second requirement outlined above. An investment adviser, on the other hand, may offer both 3(21) Fiduciary services and 3(38) Fiduciary services. Some advisers only offer one of these services, while others offer both, and will let plan sponsors pick the option which best suits their needs. As is the case with 3(21) Fiduciary services, advisors have a wide degree of latitude when deciding how to bill for 3(38) Fiduciary services. Most, however, charge plans based on a percentage of assets under management (similar to the way most advisors bill for 3(21) Fiduciary services).

3(38) Fiduciaries Have Discretionary Authority Over Plan Assets

Like 3(21) Fiduciaries, 3(38) Fiduciaries’ primary obligation is to ensure that only appropriate funds are included in a plan’s investment lineup. But whereas 3(21) Fiduciaries lack the authority to implement their recommendations, 3(38) Fiduciaries have discretion over plan assets and thus, have the authority to do so. Conceptually then, 3(38) Fiduciaries are not so much advisors (in the literal sense of providing advice), as they are also ‘doers’ (who actually hands-on manage the plan assets) – in other words, 3(38) Fiduciaries don’t ‘recommend’ adding, removing, or replacing a fund from a plan’s lineup, they just do it, akin to how RIAs with discretion over a client’s individual investment account ’just do it’ and make the trades to manage the account

Operationally, this sort of relationship can be mutually beneficial for plan sponsors and for investment advisors seeking to provide services to plans. From the plan’s perspective, the fact that the 3(38) Fiduciary can act on their own has appeal, as it eliminates an activity that would otherwise fall to the plan trustees themselves. In small businesses, the plan trustee is often the business owner (and/or another high-ranking employee) whose valuable time would more than likely be better spent elsewhere.

And from the advisor’s perspective, providing services as a 3(38) Fiduciary can reduce operational friction and increase business efficiencies. When a change is called for, the 3(38) Fiduciary can simply act to make the change they believe to be in the plan participant’s best interest, rather than wading through plan bureaucracy (e.g., first communicating a recommended change to the plan contact, then waiting for that individual to relay the suggestion to the plan investment committee, then waiting for the investment committee to meet and arrive at a decision, then waiting for the investment committee’s decision to finally be implemented…).

Liability For Investment Decisions Is Shifted From Plan Sponsors To 3(38) Fiduciaries

Another significant difference between 3(21) Fiduciaries and 3(38) Fiduciaries relates to investment liability. When a 3(38) Fiduciary is engaged by the plan, fiduciary obligations still cannot be fully delegated, but fiduciary liability for investment decisions does actually shift from the plan sponsor to the 3(38) investment manager. By contrast, when a plan engages a 3(21) Fiduciary, the plan sponsor retains liability (which is just shared with the 3(21) Fiduciary to the extent of that 3(21) Fiduciary’s investment advice recommendations).

More specifically, Section 405(d)(1) of ERISA states:

“If an investment manager or managers have been appointed under section 402(c)(3), then, notwithstanding subsections (a)(2) and (3) and subsection (b), no trustee shall be liable for the acts or omissions of such investment manager or managers, or be under an obligation to invest or otherwise manage any asset of the plan which is subject to the management of such investment manager.”

Thus, once a 3(38) Fiduciary has been hired by a plan to provide ongoing investment management, the plan sponsor and trustees are generally relieved of most of the liability related to the 3(38) Fiduciary’s investment decisions. The one caveat, however, is while the hiring of a 3(38) Fiduciary Adviser does legally shift the liability for investment decisions from the plan sponsor to the 3(38) Fiduciary, it does not absolve the plan sponsor of the fiduciary obligation to show that it acted prudently in selecting its 3(38) Fiduciary in the first place. Which would generally include making inquiries as to the skill and reputation of the Fiduciary, as well as benchmarking the fees paid for such services against other comparable vendors.

Notwithstanding the fact that the plan sponsor fiduciaries still have fiduciary responsibility to select a “good” 3(38) Fiduciary service provider in the first place, doing so may be a particularly attractive opportunity for many plan sponsors. As during the past decade alone, there have been more than 83,000 ERISA-related lawsuits filed (though not all of them are related to retirement plans).

To account for this added liability, some advisors charge more for 3(38) services than for 3(21) services. Other advisors charge the same fee for either service, and are willing to accept the added liability of being ‘a 3(38)’ as a value-add to potential clients, and/or in exchange for the operational efficiencies it creates.

Example 3: Continuing with our previous examples, after Duff Beer resolved its previous matter, it decided to engage Let’s Get Fiscal Financial Planners (A Registered Investment Adviser) for 3(38) Fiduciary services. Unfortunately, during the course of providing this service, Let’s Get Fiscal added a fund to the plan for which there was a less expensive share class available. The error was only uncovered after another plan participant brought suit.

While the above matter could certainly contribute to cultural (and similar) problems at Duff Beer, the company would at least not be liable for the fund selection error. Rather, the liability would be borne by Let’s Get Fiscal Financial Planners in their capacity as the Duff Beer plan’s 3(38) Fiduciary Adviser for recommending and implementing the wrong share class in the plan’s investment lineup.

Providing 3(16) Fiduciary Services To Help Plan Sponsors Outsource Key Administration Tasks (And Further Limit Their Liability)

One thing to which most plan sponsors can probably attest is that there’s a lot more to successfully ‘running’ a 401(k) than ‘just’ having good investment options. More specifically, there is a slew of operational tasks and administrative burdens that can present themselves to varying degrees, depending upon the size of an employer, the provisions included in a plan, and other factors. For plan sponsors who wish to outsource these duties – and further reduce liability – hiring a third type of fiduciary, a so-called “3(16) Fiduciary”, sometimes referred to as an “Administrative Fiduciary”, may be a path worth exploring.

Note that while employers work with specialized vendors known as “third-party administrators” (TPAs) to help manage the operational requirements of their retirement plans, such vendors generally serve only in an operational advice capacity and often have no discretionary authority over the administration of a plan. Thus, even though they are compensated for their services because such administrators may only provide advice regarding operational issues and that is unrelated to investment matters, they are not fiduciaries as defined by ERISA; therefore, they do not actually remove any of the administrative fiduciary liability from plan sponsors. In other words, to actually shift fiduciary liability away from a plan sponsor, the service provider must actually be responsible for doing something on the plan sponsor’s behalf (i.e., with discretion), or provide specific advice with respect to the plan sponsor’s investment matters.

Some third-party administrators, however, may offer 3(16) Fiduciary services, whereby they may take over discretionary control of some or all of a plan’s administrative and operational functions. In fact, when someone acts as a 3(16) Fiduciary, they are the plan administrator. Such activities might include:

- Filing and signing the plan’s annual Form 5500

- Distributing required documents to participants, such as the Summary Plan Description, fee disclosures, tax notices, and enrollment packages

- Verifying whether a Domestic Relations Order (DRO) meets the requirements of a QDRO

- Interpreting plan language and making decisions, such as who is eligible to participate in the plan, accordingly

- Correcting plan errors

- Signing off on distributions to participants

- Ensuring contributions are processed timely and properly

When a plan sponsor engages a 3(16) Fiduciary, they aren’t just shifting the responsibility for completing operational tasks to the 3(16) Fiduciary. Because the 3(16) Fiduciary literally becomes the plan administrator (for the activities so agreed upon), the liability for those activities is shifted to the 3(16) Fiduciary as well! Thus, for instance, if a 3(16) Fiduciary is supposed to file a plan’s Form 5500 but does not do so, the 3(16) Fiduciary (and not the business owner) who is liable for any penalties or other costs that arise from that failure.

Like other plan fiduciaries, 3(16) Fiduciaries can bill for their services in a variety of ways. Some charge flat fees, while others do so based on a percentage of assets under management. Commonly, however, the fee 3(16) Fiduciaries charge for their services is determined, at least in part, based upon the number of plan participants (given that the work of an administrator generally increases and decreases in proportion to the number of plan participants).

An Advisor’s Investment Advice And Administrative Fiduciary Duties Are Generally Provided By Separate Entities

When it comes to professional assistance with respect to a plan’s investment activities, a plan sponsor will choose between a 3(21) Fiduciary or a 3(38) Fiduciary, but will not retain both, as while there is no rule preventing a plan from hiring a 3(21) Fiduciary to provide additional guidance, a 3(38) Fiduciary is already taking on the liability for and responsibility to implement those decisions, so it does not occur in practice. (In essence, it generally wouldn’t make sense for someone hired as a 3(38) Fiduciary to take investment responsibility themselves to then hire their own 3(21) Fiduciary to get investment advice assistance.)

Investment advice and administrative duties, however, are two completely different animals. Thus, a plan sponsor can hire both a 3(21) Fiduciary and a 3(16) Fiduciary (if they want to outsource administrative duties, but retain final say over investments), or, more likely, if a plan sponsor is looking to relieve as much liability as possible, they may engage both a 3(38) Fiduciary and a 3(16) Fiduciary. Technically, there is no rule that prevents a person/business from acting as both an investment fiduciary and an administrative fiduciary. However, the specialized knowledge required to competently handle these disparate issues typically results in separate professionals being hired for each role.

401(k) plans and other retirement plans have become ‘essential’ employee benefits for employers looking to attract the best and brightest talent. But they’re a lot of work, and they bring with them a lot of liability potential for small business owners who don’t implement them properly. Thankfully, though, there are ways for advisors to provide services to employers that minimize the impact of both.

Investment advisors can offer services as 3(21) Fiduciaries, providing valuable advice to plan sponsors that can help guide them towards prudent decisions in the best interest of the plan participants (and the reduce the risk the plan sponsor gets sued for making the wrong decision about its investment lineup). Alternatively, advisors can offer 3(38) Fiduciaries to transfer both the responsibility and liability for those investment decisions to themselves as a service they provide to the small business owner.

On the administrative side, plan sponsors can engage 3(16) Fiduciaries to provide operational support for plan activities and requirements, as well as to further shift liability away from the employer. As such, offering a combination of a 3(16) Fiduciary and a 3(38) Fiduciary can be a power one-two-punch, capable of relieving a plan sponsor of most of their ongoing responsibilities and liability for the financial advisor who wants to (and is willing to) do it all.

That being said, plan sponsors always retain some responsibilities. They are responsible, for instance, for making sure that they exercise prudence when selecting any and all financial advisors to be the fiduciaries with whom the plan will engage. Furthermore, the plan sponsor must still carefully evaluate the cost of the financial advisor’s services, especially if some or all of those costs will be passed on to plan participants instead of the plan sponsor, not just as a prudent business decision but because the plan sponsor can be liable to participants in choosing an over-priced advisory firm if the additional costs borne by the participants cannot be justifiable as being in their best interests.

Ultimately, the key point is that there are different fiduciary service options that financial advisors can offer to employers to support the retirement plans they are providing to their employees. ERISA defines an advisor’s prospective fiduciary roles with different levels of fiduciary responsibility, and accordingly, each of these roles shares liability to different degrees. While 3(21) Fiduciaries offer investment guidance and share liability together with the plan trustee, 3(38) Fiduciaries have discretionary investment authority and essentially shift liability for investment decisions from the plan owner/trustee to themselves. 3(16) Fiduciaries, on the other hand, deal only with administrative issues and assume liability only as pertaining to the aspects of the plan for which they are responsible. Given the range of choices that are available, advisors themselves have a range of options in what kinds of services they do or do not want to provide, based on what they are comfortable to provide, as well as what their target clientele wish to leverage to simplify the process of providing well-designed retirement plans for their employees (and the extent to which they wish to relieve themselves of at least some of the liability along the way).

Great article. Concise and informative.

Dear Jeffrey, Great article. Two independent questions:

1) Benchmark the cost of the plan versus the market: Is there any DOL language related to the frequency of it? Any safe harbor guideline or rule? The comment of industry participants, carriers, TPA’s, is that each three years is a reasonable time frame but no one was able to provided the source of such asseveration or details of what should be included in the benchmark. Example: Same industry? Any size group?, etc.

2) I see many 401 (k) plans with companies that still have the plan active, that have done their last filing in 2017 for the 2016 year and even more cases where the filing was done in 2018 for the year 2017. Is there a penalty of monetary relevance for the plan sponsor? If yes, when does it start? And what are the penalties?

Thanks,

Roberto

Jeffrey,

You indicate that the plan sponsor has the fiduciary obligation to show that it acted prudently in selecting its 3(38) Fiduciary in the first place. But what is the scope of the plan sponsor’s continuing obligation to monitor the 3(38) Fiduciary to ensure that it was a good choice? And how does the plan sponsor do that without some education and advice, independent of the 3(38), in establishing and applying the monitoring and review criteria?