Executive Summary

Planning for individuals with disabilities poses unique challenges when coordinating across the potentially high cost of special care needs, Federal and state assistance programs such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid, and savings strategies designed to work together with those assistance programs (which themselves can have complex requirements to qualify). For example, in 2014, Congress passed the “Achieving a Better Life Experience” (ABLE) Act that created the tax-favored 529A account, providing tax-free growth opportunities for individuals with disabilities… at least, those with a disability (or blindness) that was diagnosed before the age of 26.

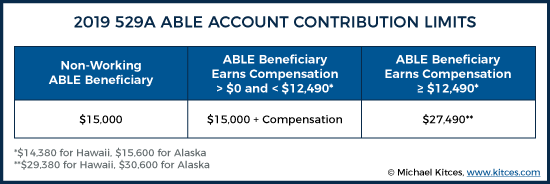

529A accounts allow for annual contributions, from all sources, of up to $15,000/year (the annual gift tax exclusion limit) plus earnings of the ABLE beneficiary, up to the annual poverty limit for a one-person household. They also allow for tax-deferred earnings on contributions inside the 529A plan, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified disability-related expenses. While contributions cannot be deducted from income on Federal tax returns, many states do allow contributions to be deducted on state tax returns. The caveat, however, is that most states also allow state-run Medicaid programs to recover expenses from 529A plans once the beneficiary has died (although five states, so far, have prohibited this, with more possibly to follow), which is important because this recovery-of-Medicaid-assistance provision has been a main reason that many individuals have opted against opening 529A accounts since they were created 5 years ago.

But despite their seemingly complex rules and restrictions – and the potential overhang of state Medicaid recovery at death – 529A accounts can still be used to effectively grow assets in a tax-efficient manner, while serving as a ‘spending account’ for a disabled beneficiary. In fact, advisors can help disabled clients to maximize the value of 529A accounts in light of state Medicaid recovery, particularly since the balance of growth and Medicaid recovery opportunities becomes especially pertinent when the beneficiary is expected to live for at least five more years.

Accordingly, the first step in maximizing the use of a 529A plan, “Contribute, But Don’t Distribute”, is to grow the account balance as aggressively and as quickly as possible in the early years in order to maximize tax-free earnings. However, the balance should be kept below $100,000 if the beneficiary is receiving any SSI benefits (though if the individual does not receive such benefits, the account can be allowed to grow to the maximum account balance as specified by the state, which is often greater than the $100,000 SSI limit).

The second step to maximize a 529A plan, “Earn and Burn”, is to systematically withdraw funds any time the account balance reaches the target threshold (to keep the account balance from exceeding the targeted limit) and to use those earnings to pay for qualified disability expenses.

Finally, the last step, “When In Doubt, Empty It Out”, applies to beneficiaries who live in states allowing for Medicaid recovery from the remaining account balance after their death. In this stage, the account holder proactively spends down and uses the 529A account, in full, if/when the beneficiary’s health takes a turn for the worse or their life expectancy otherwise becomes more limited in time horizon (to ensure there’s nothing left in the 529A account shortly before the beneficiary is expected to die).

Ultimately, the key point is that, despite the complex rules around maintaining a 529A account and the risk of state Medicaid recovery taking away the account’s remaining contributions and growth, the expenses for which a 529A account can be used are broadly defined and thus offer flexible strategies for using 529A plans for the benefit of qualifying individuals who are disabled or blind, ensuring those dollars are fully spent for the disabled beneficiary themselves.

On December 19, 2014, President Obama signed into law the Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act of 2014 as part of the “Tax Extenders” Package. The principal purpose of the Act was to create a new type of tax-favored account, aimed at helping certain persons with disabilities and/or blindness save on a tax-favored basis, and similar to a special needs trust, without impacting any means-tested disability-related benefits (e.g., Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, etc.) they might receive.

When granting special treatment to a type of account, such as a 401(k), Health Savings Account (HSA), or Education Savings Account (ESA), Congress generally subjects the accounts to a variety of rules and regulations. And 529A ABLE accounts are no exception.

529A ABLE Account Rules

It’s no accident that the rules for ABLE Accounts are found in Section 529A of the Internal Revenue Code, butting up against IRC Section 529, which provides the rules for Qualified Tuition Programs (i.e., 529 Plans). In fact, the rules for 529A ABLE accounts are largely borrowed from the existing IRC Section 529 ‘chassis’ – the extension of IRC Section 529 rules to IRC Section 529A can be seen in a variety of areas, including requirements for “separate accounting” and “limited investment direction” (i.e., investment changes limited to a maximum of two times per year), as well as to the tax treatment of the accounts.

Accordingly, just like 529 college savings plans (and other types of tax-preferenced accounts), 529A ABLE plans have strict rules around who can establish the accounts, how they can be funded, and what they can be used for.

ABLE Accounts Can Be Established By Certain Individuals with Disabilities

ABLE accounts are not available to everyone. In fact, not even all individuals who have disabilities (and/or are blind) are eligible to establish an ABLE account. Rather, only those individuals whose disability (or blindness) occurred before their 26th birthday are eligible to open such accounts (or, in many instances, have such an account opened by someone else, on their behalf).

Note that this rule does not require that the ABLE account be established before the beneficiary’s 26th birthday. It simply prohibits the establishment of such an account (whenever that establishment happens to occur) to those persons whose disability occurred after their 26th birthday.

ABLE Accounts Are Subject To Annual Contribution Limits

Total contributions from all persons to an individual’s ABLE account are generally limited to the annual gift exclusion amount ($15,000 in 2019). Notably, this is not a per-contributor limitation, but specifically a per-beneficiary limitation on the total contributions received from all sources, which means if one family member contributes the $15,000 maximum amount to a 529A plan, no one else can make any contributions for that same beneficiary in the current tax year.

Specifically, through December 31, 2025, 529A plan beneficiaries can make additional contributions (above and beyond the annual gift exclusion) of their own compensation, up to a maximum amount of the Federal poverty line threshold ($12,490 in 2019 for the continental U.S., $15,600 in 2019 for Alaska, and $14,380 in 2019 for Hawaii). Thus, cumulative contributions to a working beneficiary’s ABLE account (from all sources) may be as high as $27,490 in 2019 (for a beneficiary living in one of the 48 contiguous states or the District of Columbia who earns at least $12,490 to contribute on top of receiving a $15,000 annual gift contribution).

Of course, many persons with disabilities are unable to work. Accordingly, even with the contributions enhancements for ABLE accounts made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, they will be ‘stuck’ with the $15,000 annual-gift-tax-exclusion-amount-related contribution limit for 2019 if they don’t have any of their own compensation to contribute.

ABLE Accounts Have Favorable Tax Treatment For Qualified Disability Expenses

Contributions to 529A ABLE accounts (like contributions to 529 plans) do not receive any deduction at the Federal level, though some states offer income tax deductions for 529A contributions, such as Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Oregon (for beneficiaries under age 21), South Carolina, and Virginia.

In addition, income in a 529A plan, such as capital gains, interest, and dividends, is deferred, and may ultimately be received tax-free to the extent that it is used for “Qualified Disability Expenses” (similar to the tax treatment afforded to 529 plan distributions used for qualified education expenses). Such expenses are defined rather broadly by IRC Section 529A(e)(5), which states:

The term “qualified disability expenses” means any expenses related to the eligible individual’s blindness or disability which are made for the benefit of an eligible individual who is the designated beneficiary, including the following expenses: education, housing, transportation, employment training and support, assistive technology and personal support services, health, prevention and wellness, financial management and administrative services, legal fees, expenses for oversight and monitoring, funeral and burial expenses, and other expenses, which are approved by the Secretary [emphasis added] under regulations and consistent with the purposes of this section.

ABLE Account Balances And Distributions Generally Won’t Impact Non-SSI Means-Tested Benefits

The tax benefits of the ABLE account are quite substantial, but another important feature of the account for many persons with disabilities is its unique ability to be excluded from means testing for a variety of Federal benefits, including Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid. More specifically, Section 103(a) of the ABLE Act of 2014 provides that, in general, all amounts in an ABLE account, and any distributions from an ABLE account, are disregarded for purposes of means testing for any Federal benefits.

Section 103(a) further provides that the only exceptions to this rule relate to the SSI (Supplemental Security Income) program, and only to the extent that a distribution from an ABLE account is used for housing expenses (within the meaning of Title XVI of the Social Security Act, which is part of the Social Security Act that covers SSI), or when the value of an ABLE account exceeds $100,000. (Note: Although Section 103(a) of the ABLE Act indicates that amounts used for housing expenses are an exception to the general rule that may impact SSI eligibility, Section SI 01130.740C.4 of the Social Security Administration’s Program Operations Manual System (POMS) stipulates that distributions from ABLE accounts should not be considered income. Section SI 01130.740D.2 of Social Security’s POMS further provides that if an ABLE account distribution is spent within the month of receipt, there is no impact on SSI eligibility. If the ABLE account distribution, however, is not spent within the month of receipt and is to be used for housing expenses, it becomes an available resource that may impact SSI eligibility.)

Finally, Section 103(b) of the ABLE Act dictates that in the event that an individual’s ABLE account value exceeds $100,000, their SSI benefits will be suspended until the value declines below $100,000, though Medicaid benefits will not be impacted (as they otherwise might be if SSI benefits ceased, since SSI qualification may be required by some states for Medicaid eligibility).

In the years since the passing of the ABLE Act in 2014, many states have amended their laws to prevent state- and local-sponsored disability-related aid from being impacted by ABLE account balances and distributions in a similar manner. Thus, absent the creation of a Special Needs Trust (also referred to as a Supplemental Needs Trust), an ABLE account often provides a person with a disability the greatest opportunity to have funds accumulate for their benefit without jeopardizing valuable means-tested support programs (and with better tax-free growth benefits than a special needs trust).

Any Remaining ABLE Account Balance Can Be Recovered By Most States After The Beneficiary’s Death

Of course, when it comes to tax-favored accounts, there are usually one or more ‘gotchas!’ of which individuals should be aware, and that definitely applies to ABLE accounts.

Upon the death of an ABLE account beneficiary (the disabled person for whom the account was established and maintained), most states require that any funds remaining in the ABLE account must first be used to repay state-provided Medicaid benefits, (similar to the way that First-Party Special Needs Trusts work). Which means if the beneficiary had received ongoing Medicaid assistance (while also occasionally taking distributions from their 529A plan), all the dollars the state spent on their Medicaid benefits (which could be tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars) can be recovered from the remaining balance of the 529A plan.

Given the cost of these benefits, if the ABLE account beneficiary is receiving such aid for any meaningful amount of time prior to their death, the entire ABLE account balance at death (less any outstanding balance for qualified disability expenses incurred, but not paid before death), will, in most instances, revert to the state.

That being said, the state must file a claim in order to recover any ABLE account value remaining at the death of the ABLE beneficiary. And while states are not required to file such claims, given the possibility that such action could be taken – and often is – it is generally advisable to proceed under the assumption that any ABLE account balance remaining at the beneficiary’s death will first be used to repay Medicaid benefits, in those states that still permit Medicaid benefits to be recovered from ABLE account balances. As currently, only California, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Oregon, and Florida have passed legislation outright preventing their state Medicaid offices from filing repayment claims against ABLE accounts of deceased beneficiaries (though other states may someday follow suit).

Which means that since most – if not all – of the money in an ABLE account is likely to be used to repay the state when an ABLE account beneficiary dies (at least in 45 out of 50 states today), the 529A account is best used by those persons who are disabled, but who are not likely to die in the near term (so they have time to both accumulate tax-free growth to use, and actually have time to use it before it escheats to the state at the beneficiary’s death).

With that in mind then, a key question arises: “How exactly does an individual time contributions, growth, and distributions, to maximize the value of an ABLE account over the course of their lifetime?”

Maximizing The Lifetime Value Of An ABLE Account

To answer the question of how best to maximize the contributions to, growth of, and distributions from a 529A plan, it is first necessary to answer another question… “What is it that the ABLE account provides that can’t be replicated elsewhere?”

One could argue that the answer to this question is the unique ability of ABLE accounts to be excluded from means testing. But while that is an important benefit of ABLE accounts, it can be replicated, either via the use of a Special Needs Trust or by using a ‘proxy owner’ to ‘hold’ assets on behalf of an individual with a disability. For example, a parent could leave all their assets to a healthy child, with the understanding that half of those assets should be used for the benefit of that person’s sibling who has epilepsy.

By contrast, the preferential tax treatment of the ABLE account – its other big benefit – is far less easily replicated. And the most valuable of those tax benefits is the ability to take tax-free distributions of earnings from the 529A account to pay for qualified disability expenses. Recall that contributions to an ABLE account are made with after-tax dollars (at least at the Federal level). Thus, the spending of those dollars – whether on qualified disability expenses or otherwise – provides no tax savings. But tax-free earnings, deferred and compounded for an extended period of time, can create substantial value with a 529A plan that cannot be replicated elsewhere (e.g., with a Special Needs Trust).

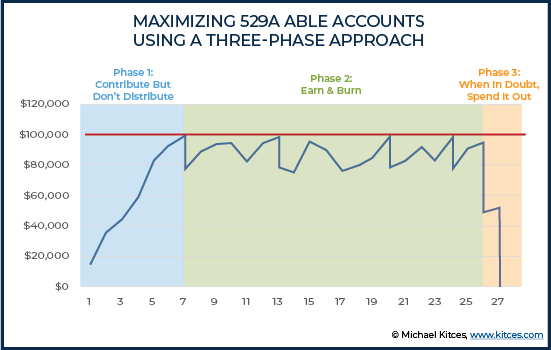

Therefore, to maximize the value of an ABLE account over the course of an individual’s lifetime, the focus should be placed squarely on how to make the most of its unique tax benefits (but without causing those tax benefits to be ‘lost’ in the state Medicaid recovery process at death). And to do that advisors can follow a three-stage approach:

- Phase #1 – Contribute, But Don’t Distribute

- Phase #2 – Earn And Burn

- Phase #3 – When In Doubt, Empty It Out

529A Planning Phase #1 – Contribute, But Don’t Distribute

During the initial years of an ABLE account, and while a person with a disability continues to have a reasonable life expectancy (let’s call this at least 5years), the primary goal should be to accumulate tax-free earnings in the ABLE account as quickly as possible.

This “Phase #1” is best accomplished by maximizing annual contribution limits (as mentioned earlier, $15,000 for 2019, or more if the beneficiary is working and can contribute their own compensation), and taking no distributions at all from the 529A plan. After all, the bigger the balance is in the ABLE account, the more tax-free dollars are created when there is growth in the account.

For example, an 8% gain on a $40,000 ABLE account balance creates a $3,200 gain that can be used tax-free for qualified disability expenses, whereas the same rate of return on an $80,000 account balance creates $6,400 of potentially tax-free gain. It’s just math, and it’s just that simple.

Allowing the balance in an ABLE account to grow in order to maximize tax-free earnings can make a lot of sense, but the point at which that no longer makes sense is generally when the total ABLE account balance (contributions plus earnings) approaches $100,000. Recall that once an individual’s ABLE account balance exceeds this threshold, any SSI benefits being paid to the person with a disability will be suspended (until the ABLE account balance drops back below $100,000).

Thus, while a number of states’ 529A plans allow for total balances well in excess of $100,000 (some of which allow contributions to accounts so long as their balances are no larger than… wait for it… $529,000!), which would make generating tax-free earnings even easier, the loss of SSI benefits (for those who receive such benefits and have a 529A plan balance in excess of $100,000), which can be up to $9,259.67 in 2019, generally makes $100,000 the effective maximum amount an individual would want to accumulate in such an account.

Example – Phase #1 (Contribute, Don’t Distribute): Jack is 20 years old with autism. He receives SSI, Medicaid, and a variety of other means-tested benefits. While his autism is severe, he is otherwise in good physical health. As such, he is expected to live for 30+ more years.

Given Jack’s facts and circumstances, Jack’s parents, who would like to save money for his future (qualified disability) expenses, decide to establish an ABLE account for Jack’s benefit. They subsequently contribute $15,000 to the account, the maximum amount Jack is eligible to receive for 2019.

And given Jack’s life expectancy, Jack (or his legal guardian) should plan to leave any contributions made to the ABLE account alone for several years, allowing the principal and accrued earnings to ‘bake’ and create as much tax-free gain as possible.

For instance, if Jack’s parents contributed the same $15,000 to the account for another 4 years (so a total of $75,000 of contributions made over 5 years), and the account grew at a rate of 6.5% per year, by the end of the fifth year, there would be roughly $91,000 in the account, including ~$16,000 worth of potentially tax-free gain.

And around that time, as Jack’s 529A plan approaches the $100,000 threshold, it would generally make sense for Jack (and/or his guardian) to move on to Phase #2 of maximizing the lifetime value of the ABLE account.

529A Planning Phase #2 – Earn And Burn

As the ABLE account balance begins to approach the $100,000 mark (or perhaps, some higher number for those persons not receiving SSI), the optimal strategy turns to the next “Earn and Burn” phase. During this phase, the goal is to repeatedly and continuously let the ABLE account balance accumulate earnings such that its balance approaches the $100,000 mark, and then to “burn” through some of those earnings by taking a distribution to pay for qualified disability expenses in order to drop the account value back down to stay below that $100,000 threshold…

But not too much below! Because remember, the higher the balance, the easier it is to generate earnings that can be distributed tax free for qualified disability expenses (which is the prime tax benefit that the ABLE account offers)!

Example – Phase #2 (Earn & Burn): Recall Jack from our previous example, who has severe autism and receives SSI, Medicaid, and a variety of other means-tested benefits. For a number of years, Jack’s parents have been contributing the $15,000 maximum amount to his ABLE account, and now, the balance in the account is beginning to approach $100,000.

Suppose that the balance in the ABLE account is $99,750. Jack, or his guardian, might distribute $4,750 tax free in order to pay for various qualified disability expenses (which, as noted above, encompass a fairly broad range of potential expenses). That would drop the account balance back down to $95,000, at which point, Jack could leave the ABLE account alone again until the balance grew enough to re-approach the $100,000 mark.

In the scenario described above, it would take ‘only’ a 5% return to fill the ABLE account back up to the $99,750. Therefore, even with a balanced portfolio allocation, it’s reasonable to assume that the “Earn” part of the Earn and Burn Phase could refill the ABLE account at least once per year, on average. And after each time, as the ABLE account balance neared $100,000, Jack could take another distribution and “Burn” some more tax-free growth on qualified disability expenses to bring the account total back down.

Rinse and repeat.

This Earn and Burn phase could last many years, and conceivably, many decades, allowing tens, if not hundreds of thousands of dollars of tax-free growth to be used, over time, to pay for qualified disability expenses. But of course, at some point, the ABLE account beneficiary will begin nearing the end of their life expectancy, whether due to age, or a deterioration in their health (which may or may not be related to a disease tied to the disability itself), which is the cue that Phase #2 – the Earn and Burn phase – of maximizing the lifetime value of the ABLE account, is over, and that its time to move on to Phase #3.

529A Planning Phase #3 – When In Doubt, Empty It Out

As a beneficiary of an ABLE account enters the final stages of their lifetime, it becomes time to enter the final phase of the ABLE account maximization process. More specifically, it may be time to go on a bit of a spending spree.

Recall that, for most states, any funds remaining in the ABLE account at the time of the beneficiary’s passing will first be used to repay state-provided Medicaid benefits, and that such amounts are likely to exceed the balance in the ABLE account (especially for ABLE accounts where the total balance never exceeds $100,000 by design but Medicaid assistance was paid out by the state for years or decades). As such, while the goal of Phase #2 was to avoid the $100,000 threshold to disqualify ongoing aid, the goal of Phase #3 is to make sure that all ABLE account funds are spent prior to the ABLE account beneficiary’s death to avoid the state Medicaid recovery at the end.

Thus, “when in doubt (about the ABLE beneficiary’s life expectancy), empty it (the ABLE account) out.”

After all, there’s no point in having funds left in an ABLE account at the time of the beneficiary’s death if they’re just going to be taken away by the state, so as death nears, it’s time to find a way to spend those dollars on some qualified disability expenses. Any qualified disability expenses. Even those that, in other situations, would be unnecessary, or perhaps even frivolous.

Thankfully, the ability to ‘find’ qualified disability expenses on which to spend any funds remaining in the ABLE account as the beneficiary approaches the end of their life expectancy is aided by the wide range of expenses that may be treated as qualified disability expenses.

In fact, in Proposed Treasury Regulations issued in 2015, the IRS went out of its way to highlight its intended broad interpretation of the statute. In the preamble to those Regulations, the IRS stated:

In order to implement the legislative purpose of assisting eligible individuals in maintaining or improving their health, independence, or quality of life, the Treasury Department and the IRS conclude that the term “qualified disability expenses” should be broadly construed to permit the inclusion of basic living expenses and should not be limited to expenses for items for which there is a medical necessity or which provide no benefits to others [emphasis added] in addition to the benefit to the eligible individual.

The Regulations even go on to include an example of how a smartphone could be considered a qualified disability expense if it aided the ABLE account beneficiary’s ability to communicate or navigate more effectively. Thus, with a little ingenuity, enough qualified disability expenses should be able to 'empty the ABLE account before the beneficiary passes.

Example – Phase #3 (When In Doubt, Empty It Out): Recall, once again, Jack from our previous examples, who has severe autism and receives SSI, Medicaid, and a variety of other means-tested benefits. For several decades, while Jack’s physical health was strong, he and his guardians used the Earn and Burn strategy to siphon significant amounts of tax-free growth out of his ABLE account.

Unfortunately, recently Jack’s health has taken a turn for the worst. Although death isn’t imminent, his doctors think there is a significant chance that he will die within the next two years. Armed with this information, Jack’s guardians begin to spend, spend, spend.

Maybe they spend $1,000 on the latest and greatest tablet to help him communicate more easily. Perhaps they purchase and modify a luxury automobile to provide him with comfortable transportation. Or maybe they use some of the money to buy a small condo for Jack, which, depending upon state law, may even be exempt from Medicaid recovery after his passing (and thus, some value may be preserved for Jack’s heirs).

At the end of the day, though, the goal is clear for those individuals on Medicaid living in states that allow state recovery of Medicaid benefits. The beneficiary will die with an ABLE account balance of $0.

If the beneficiary is not actually on Medicaid (or receiving Medicaid in one of the few states that don’t allow for Medicaid recovery), there’s no need to spend the account down before the individual dies because the remaining balance actually can be left to other beneficiaries.

Perhaps someday, many years in the future, science will advance to the point where virtually any disability will be curable with the right treatment or technology. For the time being, though, disability remains a part of life for many, including nearly 6% of children ages 5 to 17. And such disabilities often add to the regular financial burden shouldered by families as they raise children and/or support other loved ones, making any money-saving strategies that much more important.

One tool that can be used with great effect over the lifetime of an individual disabled before the age of 26 is the 529A ABLE account. Such accounts can allow persons with disabilities to accumulate up to $100,000 on a tax-favored basis, and without impacting any of their means-tested Federal benefits, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Medicaid.

To make the most of these accounts’ tax benefits, advisors should often encourage eligible persons with disabilities and/or their guardians to engage in a three-phase strategy. During the initial years in the “Contribute, But Don’t Distribute” phase, the focus should be on funding the ABLE account to the maximum extent possible. During the second phase, “Earn And Burn”, small-ish “Burn” distributions should be taken as the ABLE’s account value approaches $100,000, followed by “Earn” periods in which the account’s value is allowed to build up and re-approach the $100,000 threshold. Finally, during the “When In Doubt, Empty It Out” third phase, distributions from the ABLE account should be accelerated, at least for those who face recovery of Medicaid benefits by the state, with the intention of spending all the money on qualified disability expenses before the beneficiary’s death.

Of course, every situation is different and deserves careful analysis before decisions are made and actions are taken. And even when planning is ‘perfect’, no one has a crystal ball that can predict the future. Thus, an unexpected death could, for instance, result in the loss of many thousands of dollars accumulated in an ABLE account – of contributions and/or earnings – to Medicaid recovery.

The bottom line, though, is that 529A ABLE accounts are a valuable tool in the financial planner’s arsenal when planning for certain beneficiaries with disabilities, especially when the ‘right’ contribution and distribution strategy is used!

Can one use ABLE account similarly to HSA? That is, save the receipts from ongoing expenses and then use receipts in years to come to withdraw money from Able account.

Great article. Love the 3 phase strategy. Thank you.

I’m wondering if it’s also worth highlighting a different use of an ABLE account where finances might not be strong enough to support your longer term approach. Being able to afford their own housing and food is a challenge for many individuals on SSI… and unfortunately family/friends directly helping those individuals pay for housing or food is considered In-Kind Support and Maintenance, which impacts the individual’s SSI Housing Arrangement and reduces their SSI benefit amount.

However, my understanding is that an ABLE account can be used to avoid the above In-Kind Support and Maintenance problem, including the related reduction in SSI benefits. For example, instead of family/friends directly helping an individual pay their rent or food each month, those same funds could be put into an ABLE account by those same family/friends… and then immediately disbursed from the ABLE account to the individual with the disability… who could then use those funds to help pay their rent… and as long as the disbursement from the ABLE account and the payment of the rent happened within a given month, it would not be considered In-Kind Support and Maintenance, thus not impacting SSI Living Arrangement or SSI benefit amount. So, even if long-term accumulation of contributions to generate tax-free earnings is out-of-reach, there can still be significant benefit to cycling a third party’s funds through an ABLE account to help support housing and food expenses for someone on SSI.

Is my understanding above accurate?

You are 100% on track. Also, a trustee (1st or 3rd party) can also cycle the requires housing funds. This is one of several “workarounds” which makes ABLE such a useful tool for an adviser working with this population.

Ed,

Thanks for taking the time to read, for the kind words, and for your detailed question. So… you’re absolutely, 100% spot on about using ABLE money for housing. SSA doesn’t treat an ABLE account distribution as income, but rather, just converting one resource to another. And they only “count” countable resources as of the 1st of the month. So if an ABLE distribution is spent by that time, then it won’t impact SSI. If it’s not spent by then, that’s when it becomes problematic.

The focus of this particular article was on maximizing the long-term tax benefits of the account. But as you mention, if that’s out of reach, then using the ABLE account as a conduit to minimize the impact to SSI benefits for housing support is still a valuable use of the account and a great planning strategy!

Best,

Jeff

Indeed, I would also like to echo the thanks for addressing the important 529A ABLE topic.

One additional point that may be worth mentioning regarding the creation of the ABLE Act of 2014 is that prior to ABLE accounts, in order for a disabled individual to collect SSI benefits, “countable resources must not be worth more than $2,000 for an individual or $3,000 for a couple.” So the benefits of an ABLE account lie not just in tax savings but also in allowing a disabled individual to save a lot more than just a few thousand dollars without losing SSI benefits — which presumably can lead to a better life experience. (https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/spotlights/spot-resources.htm)

It is also my understanding that not just any disability — even if diagnosed well before age twenty-six — will necessarily convey eligibility for an ABLE account. For someone who has been collecting SSI since childhood, there may be no question as to whether they have a qualifying disability and are well suited to use an ABLE account. However, suppose a client became disabled as a teenager but has never applied for SSI, I wonder if it would be worthwhile for a financial advisor to check the diagnosis against the Blue Book (i.e., Disability Evaluation Under Social Security) or perhaps even consult with a disability attorney to confirm the eligibility of the diagnosis before recommending an ABLE account. (https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/)

Cary,

Thanks for reading and for sharing your thoughts. These are great points for advisors to consider!

Best,

Jeff

Thank you for addressing this important topic!

I’m curious about the mention of distributions for housing reducing SSI benefits. Part C-4 at https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0501130740 says “Do not count distributions from an ABLE account as income of the designated beneficiary, regardless of whether the distributions are for a QDE not related to housing, for a housing expense, or for a non-qualified expense.”

The article does say that retained distributions later used for housing should be counted as resources which reduce SSI, but part D-2 says “If the designated beneficiary spends the distribution [on housing, given the context] within the month of receipt, there is no effect on eligibility.”

This would be a big thing if ABLE accounts can be used for housing as that’s one of the big limitation of special needs trusts.

Am I missing something?

Thanks for taking the time to read and to comment. As Stefan notes below, that is absolutely correct. Provided that the ABLE account distribution is spent in the month that it is taken, spending the money on housing would have no impact on the beneficiary’s SSI. Anything not spend by the end of the month, however, becomes an available resource, that could impact eligibility. So it better be spent!

Best!

Do these comments about rent expense also apply to food expenses, which are also to be avoided with SNT money? That is, if ABLE money is spent at a grocery store in the same month it is distributed it does not count as aid for SSI? Thanks

The regs are specific on housing since it’s a date related expense, e.g. monthly. They are silent on food; however, as eating is more of any ongoing necessity I believe there would not be any restriction. One caveat might be if you are claiming that you purchase all your own food on the ISM worksheet you probably should follow the housing rule.

No, it wouldn’t apply to food. That would still be considered in kind support and maintenance which would still reduce SSI benefits. See the housing section of https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0501130740 which says “Housing expenses for purposes of an ABLE account are similar to household costs for in-kind support and maintenance purposes, with the exception of food.”

No, you have it right. Plus, a 1st or 3rd Party SNTrust can fund an ABLE to get around the housing prohibitions within those instruments.