Executive Summary

For the past decade, the growth of advisory firms has led to a wave of hiring new planners, many of whom are ultimately anticipated to be the successor to the founding owner. And as time has passed, more and more are reaching the moment of transition when the successor actually does begin to buy into the practice; in fact, even in firms where the owners aren’t looking to exit anytime soon, it is increasingly common to add “junior partners” who will help to grow the firm going forward.

However, while a great deal has been written about the ways to sell some or all of an advisory firm from the founding owner’s perspective, there is remarkably little written to guide the prospective buyer of an advisory firm – which is especially problematic, as younger buyers are often in a position of more limited negotiating power and have less knowledge and experience in analyzing an offer (and may struggle even to just gather all the appropriate information!).

Accordingly, in today’s article, we look at the dynamics and issues to consider from the buyer’s perspective when evaluating an offer to buy in as a partner. If you’re in the position of being someone’s successor, hopefully this will be a helpful primer for you on the issues to consider. And even if you’re the one looking to sell your practice, the buyer’s perspective may be helpful as well!

The Offer

You’ve been working at the advisory firm for 7 years, doing your best to contribute and grow the firm, and finally the offer comes from the 3 founding partners: you are being offered an opportunity to buy into the business.

The terms require a downpayment of $40,000, and a note for the remaining $160,000 of the purchase price, which must be paid over the next 5 years and will accrue an interest rate of 6% on the unpaid balance. In exchange for this substantial investment, you will receive a 5% equity stake in the business.

For most potential buyers into an advisory firm, this purchase will be their largest transaction ever (or perhaps second only to buying a house). And the sheer size of the transaction makes it scary for most.

But notwithstanding the size of the dollar amounts involved, the “simple” question is whether it’s actually a good deal or not? Is a total purchase price of $200,000 “fair” for the business? Can you make the hefty downpayment? If not, can you finance more of the deal? And if you do, will that just make the future cash flow obligations too onerous to manage?

So how do you evaluate the terms of the offer?

Step 1: Understand The Advisory Firm’s Profit And Loss Statement

The first step to understanding the terms of a buy-in offer and whether it is reasonable is to get up to speed on how advisory firms are valued in the first place. An excellent guide on the issue is “How To Value, Buy, Or Sell A Financial Advisory Practice” by Mark Tibergien and Owen Dahl (while it is “dated” almost 10 years, it remains remarkably timely, as the math of acquisitions never changes much!).

The first step to understanding the terms of a buy-in offer and whether it is reasonable is to get up to speed on how advisory firms are valued in the first place. An excellent guide on the issue is “How To Value, Buy, Or Sell A Financial Advisory Practice” by Mark Tibergien and Owen Dahl (while it is “dated” almost 10 years, it remains remarkably timely, as the math of acquisitions never changes much!).

The key issue is that in the end, acquisitions – whether it’s buying the whole firm, a controlling interest, or just a slice – come down to the future cash flows that business is expected to generate. In other words, it’s all about profits, and if you’re going to spend a big chunk of money buying equity, you should have an understanding of how much in profits that equity is likely to generate in the coming years. You may not have cared about these details in the past, but as an equity owner – especially once financing the purchase with debt – knowing the firm’s profit margin will quickly become important, and as a prospective buyer you should ask to see the numbers for the past several years to understand what you’re potentially buying in to.

Although all advisory firms vary a bit in their accounting, the general organization of an advisory firm’s Profit And Loss statement should look something like this:

The category of “Direct Expenses” would include all of the compensation paid to professional advisor staff – i.e., those who are directly responsible for the generation of revenue and business development. Notably, this should include a “reasonable” salary to the existing owners of the firm, for the work they do “in the business” (the remainder coming to them as profit distributions for their ownership of the business).

The next category of “Overhead Expenses” includes everything else that the firm spends money on, from salaries for operational and administrative staff, to rent and IT and software and the rest.

The rough “rule of thumb” from industry benchmarking studies is that a well-run advisory firm should spend 40% of its gross revenue on direct expenses, another 35% on overhead expenses, and be left with a 25% profit margin.

In the context of your purchase, a 5% ownership interest means a 5% share of that $500,000 of profits at the bottom, which means a payment of $25,000/year in profits distributions. To the extent that the firm grows, that payment stream will rise over time; if the business revenue declines, though, so too do the profits (at a magnified impact thanks to the overhead expenses of the firm). That’s the risk of ownership.

Step 2: Evaluate The Terms And Structure Of The Buy-In Deal

The total purchase price included in the offer for a 5% share of the business was $200,000, which implies that the total value of the firm is $200,000 / 5% = $4,000,000. Given profits of $500,000, this implies a valuation of 8X profits. Notably, a business valuation of $4M is also equivalent to the popular “2X revenue” valuation multiple for this firm (as ultimately 2X revenue is nothing more than 8X profits at a 25% profit margin anyway!).

Notwithstanding the popularity of revenue-based multipliers to estimate the value of a firm, though, as a potential owner that has a debt to pay, profits (and profit multiples) are more important. At an 8X multiple, this firm would probably be viewed as “slightly expensive” by typical valuation standards, where generally small-to-mid-sized RIAs are typically valued at 4X-6X profits, with larger firms (e.g., $500M+ of AUM) at 5-7X, and the largest ($1B+) RIAs at 6X-9X. On the other hand, if the firm can adjust/trim a bit in expenses – or happens to be having an unusually high-expense year that is suppressing profits in the short term – and the owners can get profits up to $600,000, its profit margin shifts to 30%, and its cost is now “just” 6.7X profits. Conversely, though, recognize that buying into a business generating $600,000 in profits with a $4,000,000 valuation is the equivalent of buying a stock that pays a 15% cash dividend; not bad when the S&P 500 is yielding barely 2%!

With a downpayment of $40,000 and the rest financed over 5 years at 6% for the remaining $160,000 purchase price, the ongoing payments to buy in will be $37,983/year, which is a material gap over the estimated $25,000/year in profits distributions. This means that buying in will require you to come out of pocket for not just the $40,000 downpayment, but also the roughly $13,000/year gap between profits distributions and note payments. And in point of fact, the gap will be even larger, as the $25,000/year of profits are fully taxable (as you’re now the owner of a pass-through entity!), while the loan payments are only deductible to the extent of loan interest (which will be barely 1/4th of the total payments in the first year, and decrease from there as the loan amortizes to zero).

Of course, here again the health of the business becomes even more important. If the firm can generate a 30% profit margin instead (with $600,000 of profits), your distribution comes out to $30,000, cutting the cash flow gap significantly. And if the business can grow its revenue while maintaining its profit margins, with two years of 10% growth would further boost distributions to the point that they would cover the loan payments almost entirely (at least, before accounting for taxes). Again, welcome to being a business owner – where managing profit margins and revenue growth suddenly matters, a lot!

(Michael's Note: For a much more robust tool for valuing an advisory firm, check out the "Generic" Valuation Spreadsheet from Roger Pine of Briaud Financial Advisors. You can download a copy of the spreadsheet here for your use [with Roger's permission]. Roger has made the spreadsheet available as an "Open Source" tool to the advisory community, so you can contact him directly with suggested enhancements [or questions] at [email protected].)

Step 3: Clarify What Else Would Change (Or Not?) – From Job Responsibilities To Salary To A Non-Compete

Beyond the financial terms of the deal, it’s important to clarify whether or what else might change along with your role of becoming a partner/owner of the advisory firm. In practice, this varies widely from one firm to the next. In some cases, the ownership deal is a part of broader changes for the firm. In others, it’s nothing more than the advisor doing the same job he/she was already doing, but now just participates in ownership distributions as well.

Areas of potential change to be aware of (and/or consider asking about) include:

Job Responsibilities

Will your formal job duties change as a part of your new role as a partner? Will you be expected to take on new/additional management responsibilities of some sort? Will there be (new) business development responsibilities and expectations? Will you be expected to have more responsibility with clients, manage clients alone if you weren’t already, build a team if you weren’t already on one, etc.? And of course, remember that even if your new job description as “partner” doesn’t explicitly indicate it, your ownership now expressly means you have more of a stake in all aspects of the firm’s successes, and more exposure to its risks and failures.

Control/Management

Will you have a seat at the table for major (or minor?) business decisions? Notably, as a relatively “small” minority owner, the firm is not “required” to give you a material decision-making role, and frankly you may not have the time or inclination to involve yourself in such decisions anyway. On the other hand, if the firm expects/hopes that you will want to buy into more shares in the future, and/or are part of the firm’s long-term leadership succession plan, there may be an expectation that you will take on more management responsibility whether you wanted it or not. Either way, have the conversation about expectations going forward.

Salary For The Job

As you become an owner of the firm, you may gain a newfound appreciation for the distinction between salary for the work you do in the business, and the profits distributions you receive as an owner of the business (for which you made a significant financial investment). In general, the whole point of the transaction is that you’re gaining access to the profits of the firm by paying for them, so becoming a partner doesn’t necessarily entail any change in your salary or other compensation at all. That being said, often becoming a partner is a point where other job and management responsibilities change as well, and a change in job duties should include a discussion of whether salary and related compensation should adjust as well.

Non-Compete/Non-Solicit

In many cases, signing on as a partner may involve signing a non-compete and/or non-solicit agreement, especially if you have never been expected to sign one before. And the fact that the non-compete/non-solicit is attached to a business transaction – your purchase of shares of the firm – generally makes it more enforceable, so be cognizant of what you’re signing. That being said, hopefully if you’re buying into the firm, it truly is because you’re making a longer term commitment to the business anyway, and a non-compete is a moot point. Nonetheless, be aware of what you’re signing, and be certain you have protected yourself – e.g., with reasonable limitations on the non-compete, or the right to “buy back” your own clients from the practice – if it turns out the partnership doesn’t work out.

Step 4: Negotiating The Terms Of The Succession Offer And The Structure Of The Deal

So once you’ve gotten your head wrapped about the structure of the deal, the financials of the firm you may be buying in to, and what else may change if you become a partner, the next step is to consider whether or what details you may wish to negotiate on.

First and foremost, though, it’s important to recognize that many parts of “the deal” may not be negotiable at all, either because the founders/sellers simply aren’t willing to negotiate, or because it’s not feasible given the history of the firm and prior deals that have happened. If you’re not the first partner to buy in, the odds are very good that your offer looks very similar in terms and structure to the prior one, and it would be considered “unfair” to the previous buyer to change the terms as the newest buyer. Consequently, be aware that if you’re not the first person to become a “junior” partner/owner, you may find that most of the terms of the offer are basically “take it or leave it”.

All that being said, there are still a number of ways that a deal might potentially be negotiated, even if the financial terms of the offer itself are not flexible, including:

Downpayment

Even for financing offer terms that aren’t otherwise negotiable, some firms are willing to adjust on the size of the downpayment. Of course, be cognizant that if you make the downpayment smaller, it means the ongoing payments will be larger; in the earlier example, if the downpayment is reduced to only $20,000 (10% of the purchase price), the subsequent note payments will rise from $37,983/year to $42,731/year, which means you’ll “save” on cash flow up front, but at a “cost” of higher ongoing payments.

Loan Term (Duration) and Interest Rate

If you’re the first person to buy into the practice, these details are often negotiable, especially if the arrangement is being “seller-financed” in the first place (which means the loan you’re paying off is to the owners who sold their shares to you). If the firm is requiring that you arrange your financing externally – which is typically done so the sellers receive their payment immediately as a lump sum from the bank, and then your ongoing payment arrangements are committed to the bank – the bank may or may not be as flexible in their terms. Notably, while many new buyers look to make changes to the interest rate of the loan in negotiation, in practice this has relatively limited impact, as the loan is paid off quickly anyway (e.g., cutting the interest rate from 6% to 4% only reduces the payments from $37,983/year to $35,940/year). On the other hand, adjusting the term of the loan has a very large impact; stretching payments out over more years can dramatically cut the annual payment obligation, making it easier for the profits to cover most/all of the payments sooner. For instance, if the same deal was financed over 6 years, the $37,983/year payments drop to only $32,538/year, and over 7 years it’s $28,661 and profits nearly cover the cash flow obligations right out of the gate.

Earn-Out

The label “earn-out” refers to purchase structures where the payments are not fixed up front, but instead are tied to ongoing results (e.g., “earnings” or revenues) of the business. Earn-out structures help to manage the risk of what happens particularly if earnings or revenues decline; for instance, if there was a market crash, and the firm’s revenues fell by 20%, it would chop $400,000 off the revenues of the firm, and assuming no staff are fired, that loss in revenue chops directly into profits, cutting the firm’s pool of available distributions from $500,000 to $100,000 and the new owner’s profit distribution to only $5,000, which is nowhere near enough to cover that $37,983/year payment obligation! Accordingly, an earn-out structure might say that ongoing payments are not a $160,000 note financed at 6% for 5 years, but instead a requirement to pay 0.8% of the firm’s revenues each year (payments could also be calculated on profits directly, but revenues are more common in our industry), which results in a “base” payment of $32,000/year that will adjust down if there is a revenue decline. Of course, the caveat with this arrangement is that if markets are up and the firm grows with new clientele, the buyer could end out paying far more with an earn-out arrangement; thus is the double-edged sword of shifting risk between buyer and seller!

Salary As An Advisor/Partner

As noted earlier, your salary shouldn’t necessarily change just because you’re becoming a partner of the firm, as the profits you receive from the shares you’re buying are meant to be the primary financial driver. However, to the extent that a buy-in often entails a change of duties as well, revisiting salary can be appropriate. This is also notable because while in many cases the terms of the offer aren’t negotiable, salary is, and an increase in salary (associated with new job duties as a partner) can help to close some of the cash flow gap that may emerge if the expected profit distributions cannot initially cover the loan payments. In other words, salary can be an indirect way to negotiate the net cash flows of the purchase transaction without changing the actual terms of the deal. Again, though, don’t expect or feel you’re entitled to a change in salary without some change in duties and responsibilities as well!

Total Purchase Price

It’s important to bear in mind that many of the details of the transaction may be negotiated together, and that often an adjustment to one may result in a suggested change to another, that can keep the total purchase price similar (e.g., a longer term gets accompanied by a higher interest rate to account for the risk, or a higher salary gets accompanied by a higher interest rate so the owner’s cash flows remain stable). Ultimately, though, it may be necessary to negotiate not just the detailed terms of the deal, but also the overall totality of the cost. For instance, if a net price that amounts to 8X profits and 2X revenue is just too high to be appealing, the buyer may negotiate for a lower valuation multiple. Again, though, be aware that if the terms are already locked in place because there have been prior buyers, or if the valuation multiple being offered to you is the same one that the existing partners use in their own cross-purchase buy-sell agreement, there may be little latitude here.

Notably, most firms completing a partial sale to a “Junior” partner will not let the terms of the deal reach the point where there is no downpayment and no out-of-pocket (i.e., the profit distributions completely cover the cash flow obligations to service the loan). The reason is that structuring the deal in a manner where the firm has to grow for the buyer to be cash-flow-neutral is intended as a deliberate incentive to encourage the new partner to contribute to the growth of the firm. You’re paid a salary for the work you do in the business. Participating in equity is an investment that entails risk.

In other words, just as was the case for the founders when they created the firm, an expectation that new buyers should still have some “skin in the game” and an incentive to help grow the firm is embedded into the structure of the deal. After all, there’s little incentive for founders to sell shares of their equity unless it’s with the expectation that the buyer will help grow the pie to be bigger for everyone.

Recognizing The Long-Term Opportunity Of Being An Equity Owner

While there are certainly “dangers” in managing a cash-flow-negative position for a period of years (and a host of other challenges in how to successfully transition the leadership and management of an advisory firm, which is a discussion for another day!), it’s also important to recognize the long-term potential of becoming an equity owner in a (growing) advisory firm.

After all, the reality is that after some years of contributing into the firm – both financially with out-of-pocket dollars, and with your efforts to help grow the firm (and the profits in which you now participate) – the purchase price will be fulfilled, the loan will be paid, and suddenly there are no more debt payments going out, while the equity profits are still coming in! This cash flow “pop” when the acquisition price is finally paid off can be very significant!

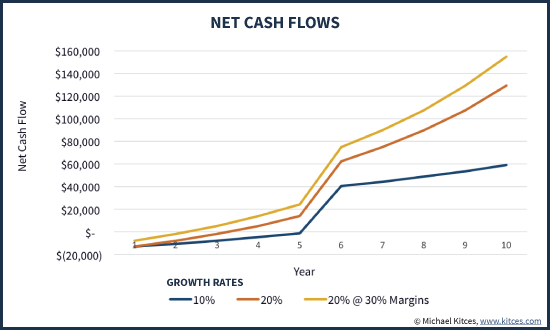

For instance, continuing the terms of the earlier transaction, imagine for a moment that the firm continues to grow at 15%/year and profit margins stay stable (although in reality they would likely fluctuate a bit). While in year 1 the profit distribution would be $25,000 and the loan payment would be $37,983, by year 3 the profit distributions would be up to $33,063, in the fourth year they would be $38,022 and exceed the loan payment (at least before accounting for taxes), and by year 5 the payments would be $43,725, leading to a small net positive cash flow. In addition, in the sixth year, the profits would climb to $50,000 – now double the original payment at purchase – and the loan would be extinguished. In other words, while for the first five years the net payments would be slightly negative or close to breakeven, in the sixth year there’s suddenly $50,000/year of profits coming out. It is crucial when considering the long-term value of a buy-in to a practice, to understand the long-term "bump" in cash flow and not fixate on the short-term (potentially negative) cash flow obligations!

And of course, from there is just keep growing. Every year thereafter. Forever. Furthermore, if the firm had grown at 15%/year and doubled over the span of 6 years, that also means the equity purchased for $200,000 is now worth $400,000 as well! And it keeps growing from there, too! Not bad for a few thousand dollars a year of net out-of-pocket expenses in those early years! In fact, ultimately it’s that potential for the long-term growth of the firm that creates the incentives to buy in, to contribute to the growth, and to help manage the expenses of the firm.

Accordingly, if the business only grows at 10%, the cash flows in year six are only $40,000/year instead of $50,000/year. If the firm grows at 20%, they’re up to $62,200/year. And if the firm can be improved to a 30% profit margin on top of that growth rate, what starts out at a $25,000 profit distribution in year 1 is up to almost $75,000/year of distributions in the sixth year, with subsequent growth from there! Again, as an owner, contributing to the growth of the firm and effectively managing the profitability of the business matters. A lot!

Of course, the consequences of mismanaging the firm, having profit margins that are too narrow to survive through market volatility, or failing to grow the business at all, mean that the future value and cash flows of the firm can swing the other direction as well. That’s the risk. Welcome to being an equity owner.

So what do you think? Are you considering whether to buy in to an advisory firm? What questions do you still have? If you've bought into a firm in the past, what do you wish you'd known then that you only discovered later? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!