Executive Summary

Conventional wisdom suggests that retirees should own a “moderate” amount of equity exposure at the time of retirement – to help their portfolio grow and keep up with inflation for a long time horizon – and then slowly decrease their exposure to equities over time as they age and their time horizon shrinks. However, recent research has suggested that the optimal approach might actually be the opposite, to start with less equity exposure early in retirement when the portfolio is largest and most exposed to a significant market decline, and then “glide” the equity exposure slightly higher each year throughout retirement.

As it turns out, though, a better approach may be to accelerate that rising equity glidepath a bit further; after all, the last bit of equity increase in the last year of retirement isn’t really likely to matter. Instead, the better rising equity glidepath approach is to just increase equities in the first half of retirement until it reaches the target threshold, and then level off. For instance, instead of gliding from 30% to 60% in equities over 30 years, glide up to 60% over 15 years and then maintain that 60% equity exposure for the rest of retirement (assuming it’s consistent with client risk tolerance in the first place).

Notably, accelerating the glidepath also reduces the amount of time that the portfolio is “bond-heavy” – a particular concern for many in today’s low-interest-rate environment. In the end, though, it may be even more effective to simply take interest rate risk off the table by owning short-term bonds instead; while such an approach leads to less wealth “on average”, in low-return environments rising equity glidepaths using stocks and Treasury Bills can actually be superior to traditional portfolios using stocks and (longer duration, e.g., 10-year Treasury) bonds, even though Treasury Bills provide lower yields!

Accelerating The Rising Equity Glidepath

In the original research Wade Pfau and I collaborated on, showing the benefits of a rising equity glidepath, we simply assumed that any retiree implementing a glidepath would move there in a straight line over their retirement. For instance, gliding equities from 30% to 45% for a 30-year retirement time horizon would be 0.5%/year, and gliding from 30% to 60% over the same time horizon would be 1.0%/year. Yet the reality in such situations is that, for someone who really is spending down assets, the last 1% change in equity exposure (e.g., from 59% to 60%) in the last of 30 years is not realistically going to impact the outcome. At that point, the retiree has either made it, or not.

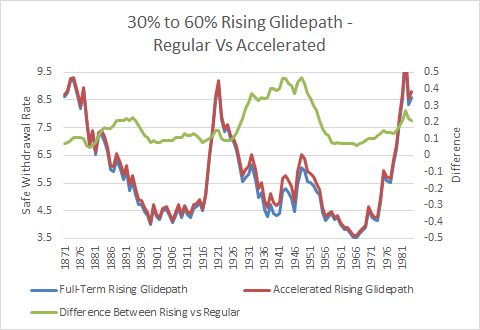

Accordingly, in a follow-up to our original research that is currently underway, we decided to test the results of an “accelerated” glidepath, where instead of moving from 30% to 60% in equities evenly over 30 years, the retiree moves there in only 15 years (at 2%/year), and then plateaus at 60% in equities for the rest of retirement. (Assuming the retiree’s risk tolerance allowed for 60% in equities in the first place, of course.) To test the alternatives, we looked at how they would have performed historically with a 4% initial withdrawal rate, over rolling 30-year periods here in the US, assuming a combination of large-cap US stocks and 10-year Treasury bonds that are annually rebalanced (to whatever the glidepath allocation would have been that year). The results are shown below, including the safe withdrawal rate that would have worked for each glidepath, and the difference in outcomes between the two.

As the results reveal, the accelerated glidepath over 15 years is superior to the 30-year rising equity glidepath. In most years, the difference is fairly small – an improvement of the safe withdrawal rate of 0.1% to 0.2% - though in the best years, the improvement was as much as almost 0.5%. Nonetheless, the results show that the accelerated glidepath is ultimately better in all historical scenarios, and improve outcomes in high-return and low-return scenarios; it’s only a question of how much.

Managing Interest Rate Risk In Bond-Heavy Glidepaths

A commonly-voiced concern of our original rising equity glidepath research was the fact that being more conservative with equities in the early years also implicitly means owning more in bonds in the early years… which is not necessarily an appealing path in light of today’s low interest rates and concerns that they will likely rise at some point in the coming years.

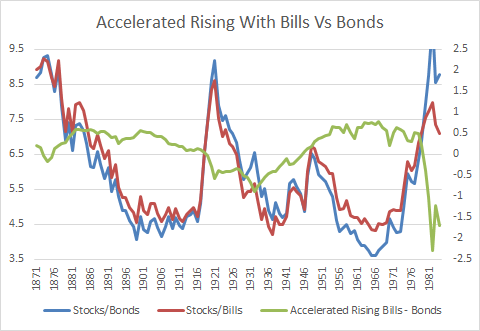

Accordingly, in our follow-up research we are also testing the impact of taking interest-rate risk off the table, by using portfolios of stocks and Treasury Bills, instead of using stocks and 10-year Treasury bonds. The “upside” of using Treasury Bills is that because they’re always maturing in a year or less, they mature and get reinvested annually, avoiding any risk that the retiree will need to liquidate bonds at a loss due to rising rates. The downside, of course, is that shorter-term Treasury Bills will generally have lower yields over time (at least in any “normal” upward-sloping yield curve environment).

As the results show below, there are times when Treasury Bills help, and times when they hurt. The difference in outcomes between using Treasury Bills and bonds is as much as a 0.5% improvement in safe withdrawal rate, and as bad as a 2% decrease. However, it is notable that in the worst of the scenarios – the mid-to-late 1960s retiree – the use of Treasury Bills is a material improvement, lifting up the safe withdrawal rate of the entire data set by almost half a point.

The reason, as is clear in retrospect, is that the mid-to-late 1960s represented the onset of what was ultimately more than a decade of rising interest rates, that led to some very significant losses for 10-year Treasury bonds with even just a "moderate" duration around 7. On top of this, it was an era of poor stock market returns as well, with a 15-year time period with almost no capital appreciation, punctuated by the 1973-74 bear market in the middle. In such an environment, it did not “pay” to take the interest rate risk of longer-term bonds on top of the volatility and sequence risk of equities.

By contrast, through the 1930s the scenario with Treasury Bills did worse (albeit modestly) than the scenario using Treasury bonds, and the difference emerges again (even more extreme) in the early 1980s. Again, in retrospect the reasoning is clear – these were times when interest rates and inflation had peaked and were falling (in the 1980s from high inflation to moderate, and in the 1930s from moderate inflation to deflation).

Ultimately, the results show – perhaps not surprisingly – that if interest rates are more likely to rise, it’s better to use equities and Treasury Bills, while if interest rates are higher and more likely to decline (or at least stay flat), it’s preferable to use intermediate- or longer-term bonds that can generate capital appreciation as rates move favorable (in addition to getting a higher yield along the way as well).

Practical Implications Of New Rising Equity Glidepath Research

While we are still in the preliminary stages of our follow-up research, the results thus far clearly suggest that if a rising equity glidepath is going to be implemented, a more accelerated one over 15 years is preferable to a 30-year rising equity glidepath. The improvement is only modest, but it helps, and it helps consistently.

However, even with an accelerated rising equity glidepath, there is still significant exposure to bonds in the early years, and the results also show that in situations where rates are low and there is an elevated risk of rising interest rates (and associated price declines in bonds), it doesn’t pay to take interest rate risk. As a result, safe withdrawal rates in the worst inflation/rising rate environments are better with Treasury Bills than bonds, even though Treasury Bills may pay “almost nothing” at the beginning of such time periods. This suggests that in the end, while it’s appealing to generate a better return from bonds if available – and higher returns will lead to higher safe withdrawal rates – in the worst environments, compounding bond risk on top of equity risk doesn’t pay. Instead, if there’s risk to bond – e.g., equities may be volatile, and interest rates may rise – the better outcome is to own the (less volatile) bonds, dollar cost average into equities, but don’t take interest rate risk in the process. In essence, the first function of bonds is simply as ballast to stocks, and should only be a return driver when there are appealing bond returns already on the table (or to hedge truly deflationary scenarios). In fact, there is actually a negative correlation (of about -0.25) between short-term bond yields and the outperformance of rising equity glidepaths using Treasury Bills; in other words, the lower interest rates are, the better it is to use low-yield Treasury Bills (due to the risk of rising rates!).

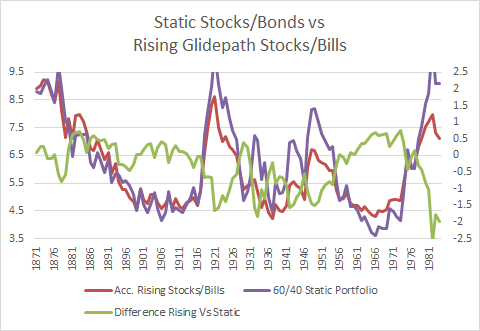

On the other hand, it’s crucial to note that using a rising equity glidepath is ultimately a more conservative lifetime equity allocation, and as a result is giving up upside in order to protect against some of the worst possible retirement scenarios – especially with an allocation to equities and Treasury Bills. Accordingly, the graph below shows the comparison of the safe withdrawal rates between a “traditional” 60/40 stock/bond portfolio (using 10-year Treasury bonds), and an (accelerated) rising equity glidepath comprised of stocks moving from 30% to 60% and Treasury Bills to fill in the rest.

In the chart, the green line again is the difference between the two, and shows that ultimately the accelerated rising equity glidepath detracts from safe withdrawal rates more often than it wins… however, the situations when it “wins” are all the situations when safe withdrawal rates are worst! In other words, the rising equity glidepath specifically gives up upside in most scenarios, to protect against downside in a subset of the worst ones. To this end, it is very much a “risk management” strategy and not a wealth maximization approach!

Nonetheless, for retirees where their paramount concern is not “maximizing wealth” or leaving the biggest pile of money to their heirs, but simply trying to maintain a stable standard of living through retirement from the highest starting point they can, these updates to the rising equity glidepath – moving through the glidepath more quickly, and using Treasury Bills (or short-term bonds in general) in low-interest-rate environments – appear to help enhance sustainable retirement income in the worst environments when it’s needed the most.

What about the behavioral issues? Easy to get a client to lower equity exposure at the start of retirement. Not so easy to get a client to slowly raise equity exposure as s/he ages.

Perhaps a phased retirement is good for the soul and for the pocketbook? Go from full-time to part-time work to stay active and reduce withdrawal needs in early years, which guards against getting whacked by a bear at the wrong time. Then use a more normal glide-path, slowly reducing equity exposure during the rest of retirement.

Robert,

Remember, if ALL the client does is just SPEND THEIR CASH and do NOTHING else, they are already increasing equity exposure as they age, by the mere fact that the fixed portion is being spent down while the equities grow over time.

This doesn’t necessarily require ever buying equities, when client spending is 4%/year and the targeted rising equity glidepath is only 1%-2%/year. The only time you’d actually be buying equities is when you’d “want” to – after they’ve declined, when it’s time to do the same rebalancing transaction you’d encourage any client to do, regardless of whether their glidepath was rising or steady or falling…

– Michael

So how would the mechanics work? If the original equity allocation dropped from 30% to 15% after the first year, would you sell bonds to bring the percentage back to 30% (plus another 2%) for the second year assuming the accelerated glide path?

If so, that could deplete the bond/safe allocation pretty rapidly.

Any thoughts?

Great suggestion, Robert. I also think other types of higher-yielding alternatives could be introduced into the portfolio — REITS, BDCs, etc. — to add some juice to the fixed side and provide some dis-correlation to bonds.

Phil,

We don’t have the data history to test BDCs, but REITs would not fare well in this analysis. Publicly traded REITs have exhibited increasingly high correlations to equities, and the real point here is NOT to have things with a low correlation to BONDS, it’s having investments with a low correlation to EQUITIES (which is part of why Treasury Bills fare so well).

– Michael

I understand the correlation issue. Definitely non-traded REITs and non-traded BDCs.

Phil,

Just because they’re non-traded doesn’t mean they aren’t volatile, it’s just that the clients can’t SEE the volatility.

From a more practical perspective, using non-traded illiquid vehicles eliminates most rebalancing opportunities, which may be problematic, especially in volatile times. The whole reason why stocks/Bills works so well is that the Bills are ballast that can be reinvested into equities when rebalancing during/after market declines, but that’s generally not an option for non-traded vehicles.

– Michael

The illiquidity and high fees associated with these products would rule them out in my book. Sure your return is higher but it’s not needed. That’s what the stock portion of the portfolio is for.

Any thoughts on longevity insurance as proxy for a portion of equity exposure and spia’s on the front end ?

Jim,

I’m fascinated by the potential for longevity insurance to be a part of this. I wrote recently on the products as a part of the new QLAC regulations (see http://www.kitces.com/blog/why-the-new-qualifying-longevity-annuity-contract-qlac-rmd-regulations-for-dont-mean-much-for-retirement-income-yet/ ) and the next two full issues of my newsletter (www.kitces.com/newsletter) will be studying them as well!

I’m not quite sure they’re the perfect solution either, but there is some really interesting potential for sure…

– Michael

To remove the interest rate risk and get a much better return than Treasury Bills or short-term bonds, why not create an income ladder of bonds held to maturity that extends over much of the first 15 years or so of retirement? By design, the real value of successively later rungs could even decrease over the years, with the intention of drawing more from equities each year for living expenses during the first 15 years. (Treasurys currently yield about 0.11% for a 1-year STRIP and over 3% for a 15-year STRIP — that’s too big a big spread to ignore…)

Julian,

But how will you replenish the ladder?

If you systematically maintain a 15-year bond ladder, then every year you liquidate a bond and replace it with a new bond (which in turn is funded from the stock portfolio), then all you’re actually doing is maintaining a rolling 15-year bond ladder and doing 100% of spending from equities, which is even worse.

And if you don’t replenish the bond ladder, the client will be 100% in equities in 15 years, which probably isn’t better (at least from a client behavioral and regulatory perspective).

– Michael

You could rebalance the portfolio when it is not disadvantageous to do so. Over a 10-15 year period of time you will have opportunities to do so. Most bear markets don’t last 15 years. Also, why go out 15 years on the ladder. Too much risk. Stay short term, say 1-5 years. You can still “protect” 15 years of cash flows and stay short.

Rather than creating a 15-year ladder, you can create a shorter ladder, say 7 years, populated with multiple bonds/CDs maturing annually and representing more than what is needed to live on annually. As the bonds/CDs mature there is some flexibility to use them for living, purchase new bonds/CDs, or purchase equities (assuming your allocation is below the desired glidepath). Likewise, if equities are substantially above the target glidepath and are near all-time highs, some equities can be liquidated and reinvested in bonds/CDs. Any glidepath is going to need some attention and thinking as one progresses through retirement.

It would be interesting to know how much (or little) successful risk management on the static 60/40 would have to employed to wipe out most/all scenarios where the glidepath wins. My sense is it would not take much, so if allocation tactics are being used with the expectation of reducing volatility, it seems the glidepath would not be an added help.

Mark,

Indeed, part of what we’re also testing in this follow-up research is the impact of more valuation-based tactical asset allocation, as an alternative to purely mechanistic glidepaths (rising or falling, accelerated or not). Preliminary results have been “interesting” to say the least. Stay tuned for more research soon! 🙂

– Michael

Yeah…can’t wait for the “rest of the story”!

It seems like the bottom line is this: If we believe market valuations are currently high (I do); then the accelerated glide path, i.e., beginning retirement at 30% and adding 2% equities each year until you get to 60%, is more likely to end successfully then the static 60/40 split or a declining equity glide path. It is also notable that a “set it and forget it” 60/40 split seems to be very effective across most valuation scenarios. Or am I missing something?

I assume that the 30% equity exposure would also include any foreign funds owned?

So here we are in the late fall of 2021–we’ve been through the quickest recession and quickest recovery on record. Stocks are at all-time highs and moving up while interest rates are still very low and inflation is running over 5% annually. Do you have any updated data showing how portfolios which were following rising glidepaths have done? My suspicion is they have done well but out performed by 60/40 split portfolios. However, going forward, it’s less clear that the likely outperformance will continue.

As we look at interest rates currently, Government bonds are doing terribly but the interest rate for Series I-bonds has just reset from about 5.4% to over 7%. This suggests that they may be an overlooked but helpful location to invest a portion of one’s bond assets especially if one has excess assets that won’t be needed for several years.

Another option and one closer to home for me is to stay 100% stock index funds till retirement and this increases chance of wealth & only needing something south of 3% withdraw rate to retire on. Lower withdraw rates work with 100% stocks. Swap some safety of bonds for a lower withdraw rate. Does it balance out? The lifetime at a more aggressive allocation most likely gave you more wealth and thus your lower withdraw would have been the same in the alternate world where you put more in bonds.