Executive Summary

For an advice-giver, the “ideal” client is one who presents a clear fact pattern to analyze, for which there is a single straightforward recommendation to implement, that the client immediately takes up and follows through on. In the real world, most clients are more complex, and entail a long series of recommendations to implement over time… which means, at best, even the most diligent clients won’t necessarily follow through on everything right away. And for many, over time, it can become even harder to finish all the implementation steps, as other demands and distractions of life sap the client’s focus and motivation.

Yet the growing base of research on “non-compliance” (or at least, “non-adherence”) to advice-givers in the medical world (i.e., patients who don’t follow their doctor’s advice and prescriptions) reveals that the burden for following through on implementation should not rest solely with the patient or client receiving the advice. Instead, the reality is that the advice-giver also has a role to play, and a shared responsibility to ensure that the advice they give actually “sticks.”

And in her recent book of that name – “Advice That Sticks” – neuropsychologist Dr. Moira Somers explores how the adherence research on advice can be applied to the world of financial advisors to actually increase the likelihood that clients really do follow through on all of their recommendations.

The first key insight of the research is that clients hire financial advisors for a wide range of reasons – far beyond “just” seeking out answers to their financial questions. In fact, given the ever-growing depth and reach of the internet, clients are arguably less and less likely to be seeking answers and expertise alone. Instead, they may be seeking someone to help them make sense of all the information, to reduce complexity or help them evaluate trade-offs, or increase their confidence about their own decisions. In other cases, the client may actually be hoping to delegate something – not just the responsibility for managing their assets, but the “unpleasantness” of spending time in an area they don’t relish, to have someone (else) to blame if things go wrong, or simply to free up their own time for other endeavors.

And in addition to the fact that clients come to advisors for more than “just” advice alone, Somers highlights the wide range of additional influences that can impact the client’s receptivity to advice, from their own personal financial history and circumstances (and the “money scripts” they’ve learned from prior experiences), to their social and environment factors (where they may not be prepared to face the family consequences of a financial decision), to the nature of the advice itself (long-term preventative advice is the hardest to implement in the first place), and how the advisor’s own advice-delivery process can impact the outcomes.

Ultimately, though, the key point is simply to understand that clients who don’t implement the advice they’re given aren’t necessarily “bad clients” for failing to do so. Instead, the advice-giver themselves has a proactive role to play in aiding clients to follow-through and implement, and in reality the client who faithfully and fully implements all their advice the first time and never needs help on follow-through again is not the paragon of being a good client but more the exception to the rule for how most people actually struggle to implement even good advice. On the plus side, though, that means there is tremendous additional value to be created for clients by not just giving the most accurate good advice, but actually being the best at giving advice that sticks, too.

Good Clients Versus “Bad” Clients Of Financial Advisors

In financial advising, as with many businesses and industries, the famous “80/20” rule tends to hold that 80% of the profits come from the top 20% of the firm’s clients. More generally, it’s common for advisory firms to have a mixture of “good” clients, who have the financial wherewithal to compensate the advisor for his/her time and services, and a number of “bad” clients who aren’t necessarily profitable for the firm, but ones the advisor has chosen to serve anyway.

Another way to look at “good” versus “bad” clients, though, simply that some clients are “good” because they’re easy and pleasant to work with, while others are “bad” clients who don’t adhere to their meetings, don’t follow through on their recommendations, and simply don’t actually take the advisor’s advice (despite ongoing meetings to remind them of what they still need to do). In fact, some advisors go so far as to say they won’t even take, or will outright “fire” clients who don’t take their advice – recognizing both the unfulfilling nature (for the advisor) of repeatedly giving the same advice to someone who doesn’t implement it, and the potential liability that the advisor may fear if the client’s financial situation takes an even worse turn (and the advisor is blamed for the client’s inaction).

Yet the challenge of getting people who ask the advice of a professional to actually take that advice it isn’t new. The phenomenon has been increasingly well researched in the medical industry, where doctors give advice and recommendations (from new eating habits and exercise regimens, to prescription drugs and physical therapy) but patients don’t necessarily follow through – a phenomenon called non-compliance. In fact, some researchers have suggested that Non-Compliant Behavior (NCB) of patients may actually be one of the most common causes of treatment failure for chronic health conditions.

And what the medical profession has learned over several decades of research since the phenomenon was first recognized is that a patient’s non-compliance with their doctor’s recommendations can sometimes be as much a problem with the doctor giving the advice than the patient (failing to) take it. In other words, there really is such a thing as “good advice, badly given.”

In fact, it ironically turns out that one of the reasons that patients sometimes fail to comply with the advice of their doctors is that the very nature of the doctor-patient relationship implies a power differential that can make patients feel uncomfortably “judged” for an impliedly defiant act of non-compliance instead of simply recognizing that they may have felt overwhelmed or confused or helpless and unable to adhere to the advice that was given… and thus why the research now focuses on patient “non-adherence” versus “non-compliance” instead.

The fundamental point, though, is simply to understand that the advice-giver has a role in the process, not merely to give the technically accurate and correct advice but to deliver the advice in a way that increases the likelihood that the client will adhere and “stick” to it. Which, in her new book, “Advice That Sticks”, neuropsychologist Dr. Moira Somers applies for the first time directly to the world of financial advisors, and explores how we can leverage the research on non-adherence in the medical realm to give better “advice that sticks” with clients, that they will adhere to and actually follow through on in order to no longer be “bad” clients!

The fundamental point, though, is simply to understand that the advice-giver has a role in the process, not merely to give the technically accurate and correct advice but to deliver the advice in a way that increases the likelihood that the client will adhere and “stick” to it. Which, in her new book, “Advice That Sticks”, neuropsychologist Dr. Moira Somers applies for the first time directly to the world of financial advisors, and explores how we can leverage the research on non-adherence in the medical realm to give better “advice that sticks” with clients, that they will adhere to and actually follow through on in order to no longer be “bad” clients!

10 Reasons That Clients Actually Seek Out (Financial) Advice

The first key in figuring out how to better get financial advice to better “stick” to clients is to really understand why clients seek out a financial advisor for advice in the first place.

The conventional wisdom is that clients are seeking the answer to a financial question. “I have a problem. I need an answer. Here are the facts and circumstances of my situation. Tell me what I should do.” For which we then run our financial analyses, and then deliver The Plan with recommendations about how best for them to proceed.

Yet as Somers points out, while the essence of advice-seeking behavior is to get help in solving a problem, it’s not always just about finding “the answer.” After all, if the answer is simply a piece of factual information, in today’s internet age we can simply look it up directly, or ask Uncle Google or Aunt Siri or Aunt Alexa.

And not only do consumers have ever-growing access to more and more information directly and for free, but seeking out and getting financial advice still has a material cost as well. Which means in practice, a client must be in some non-trivial amount of unsettled discomfort to be willing to go through the trouble of finding and hiring and paying for (and then hopefully taking advice from) a financial advisor.

The significance of this cost barrier and the mental motivators it takes to overcome it is that, as Somers points out, there’s an inherently emotional component to the advice-seeking process, that drives the answer to the questions “why is it so important to get this answer to this problem” and even more significantly “why now” seek out the advice in the first place?

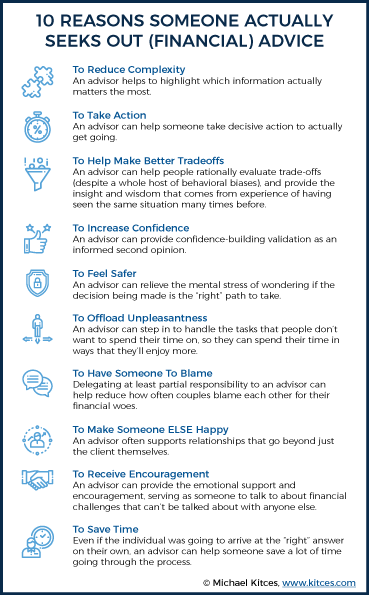

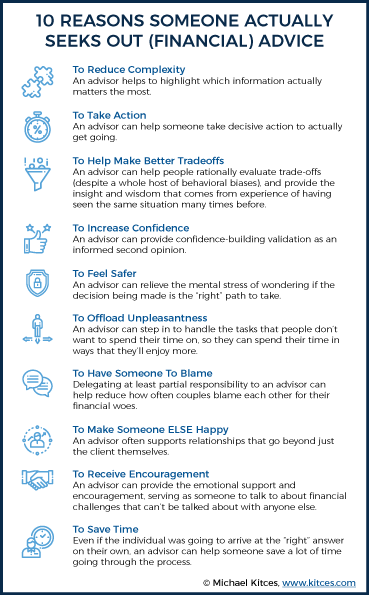

In fact, Somers identifies 10 different reasons that clients may seek out expert advice (and choose to act now), that don’t necessarily have much to do with (just) the actual answer to their financial problem or issue but speak to a broader motivation for seeking out advice, including:

2) To Take Action. A corollary challenge to the sheer volume of information available at our fingertips today is that not only can it be difficult to separate the signal from the noise, but that the flood of information may be so overwhelming it causes an “analysis paralysis” as the overwhelming number of choices results in inaction. An advisor can help someone take decisive action to actually get going.

3) To Help Make Better Tradeoffs. Simple financial trade-offs are simple to evaluate (e.g., a CD yielding 2% is better than a savings account yielding 0.50% if you don’t need the money anyway), but complex trade-offs are much more complex to evaluate (e.g., is it better to retain the flexibility of the portfolio but also the risk, or annuitize assets for a lifetime stream of income that also eliminates any possibility of things getting better than they are today?). An advisor can help people rationally evaluate trade-offs (despite a whole host of behavioral biases), and provide the insight and wisdom that comes from the experience of having seen the same situation many times before.

4) To Increase Confidence. Sometimes even after doing all the homework, and making a choice on the path forward, a second opinion is still valuable to help ensure that nothing important was overlooked. Because even if the decision and outcome don’t change, and the second opinion simply reaffirms the originally chosen path, it’s still reaffirming to get the confirmation. An advisor can provide confidence-building validation as an informed second opinion.

5) To Feel Safer. Because stressful financial decisions are just that – stressful – often it’s just outright mentally relieving to know that there’s an expert to rely upon, as our brains literally offload the “work” of the decision-making process when an expert is involved, saving the mental toll of even trying to figure out what the best path forward should be and the worry that it may be the wrong one. An advisor can relieve the mental stress of wondering if the decision being made is the “right” path to take.

6) To Offload Unpleasantness. In some cases, the blocking point for someone to do their own research and analysis to come up with the answer isn’t that they don’t have the skills, or the time, or the mental fortitude to handle the stress of the decision, but simply that they don’t like or want to do it, and would rather do something else with their available time. An advisor can step in to handle the tasks that people don’t want to spend their time on, so they can spend their time in ways that they’ll enjoy more.

7) To Have Someone To Blame. It is common for many couples to delegate financial responsibility to one member or the other… which, for some, is incredibly stressful knowing that if their financial situation takes a turn for the worse, they must personally face the wrath of an unhappy spouse or other family members. Delegating at least partial responsibility to an advisor can help reduce how often couples blame each other for their financial woes.

8) To Make Someone ELSE Happy. While most of the time, individuals seek out advice for themselves, sometimes the purpose of meeting an advisor is for someone else… either because they’re seeking advice on behalf of someone else, or simply because someone else has demanded that they seek help (e.g., a parent who says “you need to find an advisor because you can’t handle this inheritance by yourself). An advisor often supports relationships that go beyond just the client themselves.

9) To Receive Encouragement. For most people, money is a taboo subject, more so even than religion, politics, or sex. Which makes it especially difficult to find words of support and encouragement from friends and even family in the midst of making difficult financial decisions or changes. An advisor can provide the emotional support and encouragement, serving as someone to talk to about financial challenges that can’t be talked about with anyone else.

10) To Save Time. Even in the best of circumstances, a consumer who can both sift through the voluminous information to separate the signal from the noise and determine the best decisive course of action will still likely take a lot of time to go through the process… time that not everyone has. Even if the individual was going to arrive at the “right” answer on their own, an advisor can help someone save a lot of time going through the process.

The reason these reasons-for-seeking-advice are so important is that it highlights how the intention of an advice-seeker is often not actually about the advice-answer itself! Which in turn, helps to explain why clients don’t necessarily follow through on “the answer” when the recommendation is provided to them!

Because if the real reason for meeting with the advisor was to make someone else happy, the client’s goal might have been accomplished by just showing up, not by following through! Alternatively, if the client’s intention was actually to offload unpleasantness or have someone to blame, or simply to save time, the client may not have wanted a recommendation of what to do, and instead actually wanted the advisor to do it for them!

Simply put, if the advisor doesn’t consider the true reason for why a prospective client is seeking out their advice, it’s hard to figure out why they do or don’t implement the subsequent recommendations (or whether they ever actually were going to in the first place!)

Accordingly, as a starting point, Somers suggests that it would be wise to start every client meeting asking questions like:

- “What would make our time together today the best use of your time, energy, and money?”

- “What are you hoping will happen as a result of our meeting?”

- “Aside from the obvious, is there anything else that brings you here today?”

Similarly, advisors can then wrap up each meeting by asking both:

- “When I asked you about what you most wanted to accomplish as a result of our meeting today, you told me (insert answer here). Did we accomplish that?”

- “Is there anything that is [still] leaving you unsettled or unsure?”

The FACTS That Limit Clients From Following Through On Advice That Sticks

Beyond just the purpose of why the client is seeking out the advice in the first place, Somers also observes that there are multiple domains that can all impact whether or why a client will likely implement the advisors’ advice (or not).

Following the acronym FACTS, the five domains are:

- Financial History and Circumstances – Consumers facing financial scarcity or high-stress personal circumstances can hyperfocus and “tunnel” their attention on a single issue and miss the bigger picture, increasing the challenge and complexity of successfully making advice stick. In addition, money scripts learned in one’s early years can shape their later views and how they approach financial problems, making it necessary to understand the client’s financial past to understand what kind of advice they will even be willing to take in the future.

- Advice Characteristics – A lot of the advice we may give as advisors is difficult to follow simply by its nature, often dealing with broad lifestyle changes that are long-term and preventative (which means there’s no immediate relief or positive results to reinforce the behavior, thus why it’s often beneficial to break financial advice it up into smaller pieces), and often requiring people to act against their impulses (i.e., ignore all those commercials and ads!) and not do what everyone else is doing (i.e., it’s much harder to take advice to not keep up with the Joneses!).

- Client Characteristics – Notwithstanding their decision to go and see an advisor, some clients are not really ready to actually make a change yet (a phenomenon first discovered by psychology researcher Prochaska), and even those who are ready will often still need hand-holding or support to keep them motivated. Advisors tend to think that the advice is done once clients are given their recommendations of what to do and leave the office, but the behavior change research tells us that relapse is normal, and most people need help and later reinforcement to stick with a difficult change. Thus why a key part of advising towards behavior change is not just about giving clients the information of what to do but also helping to motivate them to do it and gain the confidence that they can do it successfully.

- Team (and Advisor) Factors – A key discovery of the non-compliance-turned-non-adherence research in medicine is that the client’s (or patient’s) success in following through on the recommendations provided is a shared responsibility of the advice-giver and the advice-receiver. Which means not only is it important to avoid using too much industry jargon that clients don’t understand, but it’s equally important to make sure that clients feel emotionally safe and don’t feel judged for the problems they’re bringing to the advisor’s table.

- Social and Environmental Factors – Even when a client comes to an advisor for advice, the advisor is likely not the only person influencing the client’s decision-making process. Not only because many people have other friends and family they use as confidants and seek out advice from, but also because financial decisions often have real-world ramifications for other people in the client’s life, and the client may or may not be fully prepared to deal with those consequences. For instance, it’s one thing to say that parents need to cut off their adult children’s financial support to secure their own retirement but are the parents really ready to have that conversation with their kids? At a minimum, understanding social and environmental factors highlights the kinds of additional support (emotional, informational, instrumental, or simply companionship) that clients may need to see the advice through to the end, and gives the advisor an opportunity to help them prepare them in advance for how they’ll handle those difficult situations.

Assessing Client Readiness To Take Financial Advice And Make Financial Changes

The key point, though, is simply to understand that the issue of why a client does or doesn’t take and follow through on advice is much more complex than just “he/she is a ‘bad’ client.”

In reality, clients are influenced by many different factors that may impact whether they follow through on advice or not, many different reasons for even seeking out the advice in the first place (which may or may not have to do with any intention of following through on it), and the advisor themselves has an important role to play, both in not impeding the client’s progress forward by being unwittingly jargoned or judgmental, but also because the very process of giving advice itself can and arguably should be adapted to the client’s reasons for seeking advice and circumstances for following through on it.

In fact, Somers herself suggests a series of 3 “readiness” questions that advisors should consider asking, at the end of any meeting where recommendations are given, to affirm (or simply determine) whether clients are really even ready to follow through on the advice:

“How would you feel about (insert recommended action here)?” Does the client really WANT to focus on this?

“If you decided to (insert recommended action here), how would that benefit you?” Does the client really see the benefits and have an emotional connection to following through?

“If you decided to go ahead with this step, how confident are you that you could do it?” Because if the client doesn’t believe they can succeed in implementing the advice, they won’t.

Unfortunately, the reality is that historically, as financial advisors we aren’t taught these lessons of how best to actually deliver advice to maximize the odds that clients follow through on it, advisory firms don’t have any standardized way to assess and measure the “quality” of their advice-delivery process, and there is not (yet!?) any “adherence research” in the domain of financial planning.

So what do you think? What are some ways that advisors can help clients adhere to the advice that they've asked for? Are there ways to tweak your workflow to make it easier for clients to implement your recommendations? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!