Executive Summary

The career path of becoming a financial advisor has long been lauded as an opportunity that pairs together a high income potential with the flexibility of building your own book of clients (or the outright benefits of being an entrepreneur building an independent business). The caveat, though, is that while financial advisors do generate an income far higher than the national average, there is also a great deal of stress in building an advisory business from scratch and just trying to survive long enough to enjoy that income. Not to mention the reality that, as the saying goes, “You can’t take it with you”… raising the question of whether the stressful pursuit of a financial advisor’s income potential is even ‘worth it’ in the long run?

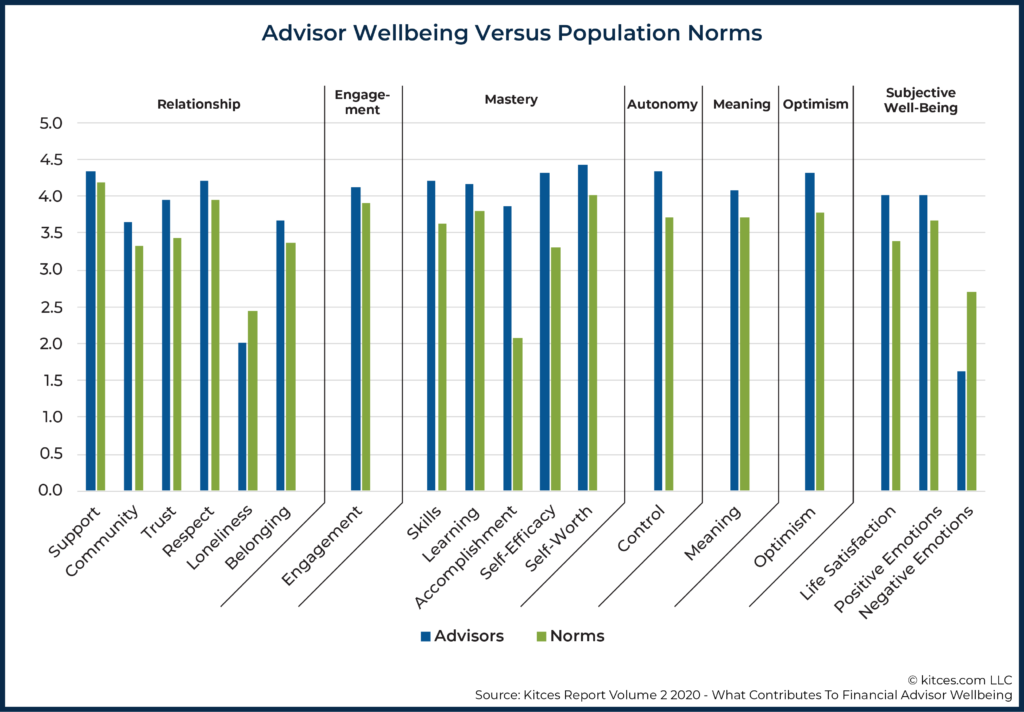

But as the latest Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing shows, financial advisors do in fact enjoy not only above-average income, but above-average wellbeing in all 18 sub-scales of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (a comprehensive measure of wellbeing). And in fact, while the average American typically reaches a point where their wellbeing stops rising once they achieve a certain level of income, financial advisors continue to report ever-greater levels of wellbeing as their career earnings continue to grow with additional years of experience!

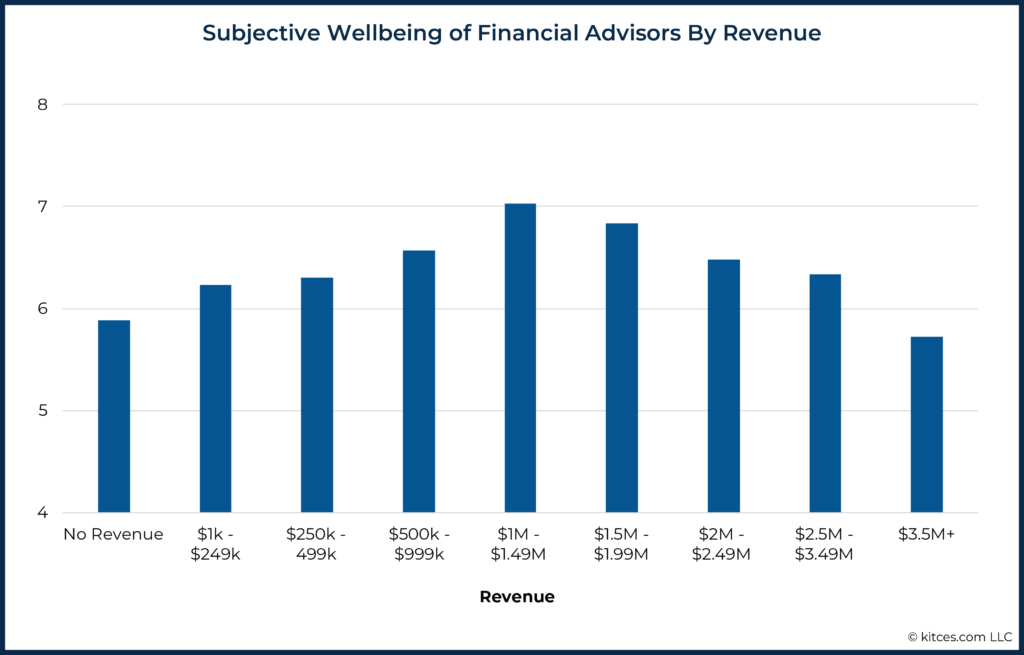

The caveat, though, is that while advisor wellbeing does rise as income grows, advisor wellbeing actually begins to decline once the aggregate revenue of the business exceeds $1.5M. And on average, the higher revenue grows from there, the lower the self-reported wellbeing of financial advisors themselves! The shift appears to be driven by the reality that once an advisory firm grows materially beyond $1.5M of revenue, it is virtually inevitable that the advisory firm takes on multiple lead advisors, and a growing team infrastructure to support them… transforming the founder’s role from being the advisor they first set out to be into becoming a manager instead, while simultaneously increasing their hours worked and reducing the autonomy they have over their time and schedule. All of which are associated with lower wellbeing.

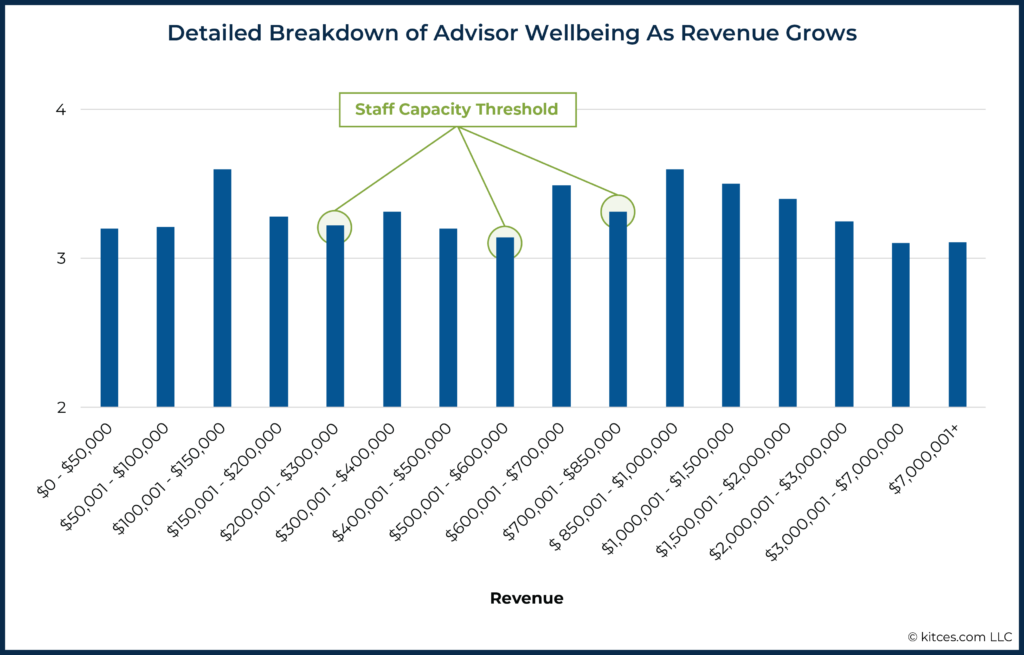

Of course, given that most advisors haven’t even reached $1M+ of revenue, many might wish they had such ‘first-world’ problems. However, our Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing also shows significant dips in advisor wellbeing at approximately $275,000, $550,000, and $825,000 of revenue… all of which are associated with capacity thresholds where advisory firms must hire to service their ever-growing number of clients. Which means in practice, advisory firms actually face a series of repeated barriers that reduce wellbeing… all associated with hitting the capacity limitations of serving clients, and what happens when the firm either doesn’t hire early enough, doesn’t hire enough at all… or hires so many people that the founder primarily shifts to becoming a manager of that team (instead of an advisor).

Ultimately, though, the key point is simply to recognize that in the end, it’s maximizing the value of our time – and literally generating the maximal revenue from the minimal time – that appears to be one of the greatest drivers of advisor wellbeing. Which means the key to “happy growth” is not just adding more clients, but specifically increasing revenue per client (by attracting and serving more affluent clients who can pay higher fees) that allows advisors to do their most rewarding work. Even if, in the long run, that actually means working with fewer clients… who most value the time and value that their financial advisor provides!

Advisor Wellbeing Is Driven By Income Over Pure Revenue

The question of “what makes human beings happy” has been debated by philosophers for several millennia. Yet while certain principles have held constant throughout, it turns out that the question is driven, at least in part, by how, exactly, one’s “happiness” is defined, from the emotional state (“I feel happy in this moment”) to the overall sense of satisfaction with life.

Defining Wellbeing

Modern researchers have expanded the framework into what is now known as “wellbeing”, which represents “a measure of how people experience and evaluate their lives and specific domains and activities within their lives”. Accordingly, tools have been developed to measure wellbeing across these domains, such as the well-known positive psychology measure known as the “Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving” (CIT). The CIT has within it 18 different subscales that address many aspects of what it means to “thrive” and have wellbeing (e.g., relationships, engagement, mastery, autonomy, meaning, optimism).

One of the subscales within the CIT is a specific measure of subjective wellbeing – how we assess our own sense of wellbeing. The subjective wellbeing subscale is measured using three sets of questions about life satisfaction, positive feelings, and negative feelings, on which individuals can rate themselves on a 1-4 scale based on the extent to which they either disagree (1) or agree (4) with the statement:

- Life satisfaction: In most ways, my life is close to my ideal, I feel satisfied with my life, and my life is going well;

- Positive feelings: I feel positive most of the time, I feel happy most of the time, and I feel good most of the time; and

- Negative feelings: I feel negative most of the time, I experience unhappy feelings most of the time, and I feel bad most of the time.

And in our latest Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing, it turns out that financial advisors score well on wellbeing. In fact, relative to general population norms, financial advisors score above-average on every subscale of wellbeing in the CIT, outscoring on all the positive measures (particularly the measures of accomplishment and self-efficacy), and favorably ‘underscoring’ on the negative (i.e., advisors have fewer negative emotions and experience less loneliness). In the context of subjective wellbeing, in particular, advisors scored quite strongly on all three measures, rating themselves higher on life satisfaction and positive emotions, and substantively lower on experiencing negative emotions.

Take-Home Income And Advisor Wellbeing

Of course, the reality is that even if the average financial advisor is ‘happy’ and experiences above-average wellbeing, that doesn’t mean all advisors do. In some cases, that’s because there are individual factors in their personal lives that influence their wellbeing (for better or worse) that have no relationship to the fact that they’re financial advisors in the first place. In other cases, though, there are differences in the wellbeing of financial advisors that are driven directly by the traits of their advisory practice.

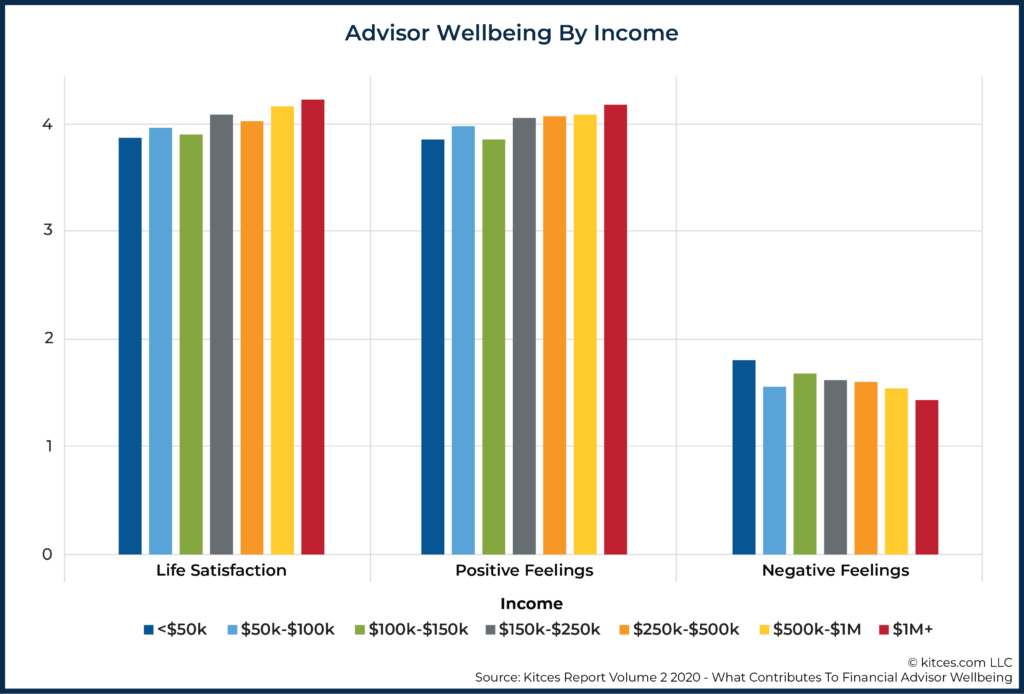

In fact, our Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing reveals that income – or more specifically, the advisor’s total take-home pay after all grid cuts, expenses, and other costs of the business are accounted for – is one of the most significant contributors to advisor wellbeing. In other words, it turns out that, with financial advisors, “money really can buy happiness”, at least to some sizable extent.

Perhaps you might think, “Okay... great. I could have told you that!” or, “Why would Kitces write an article on something that seems so obvious? Who doesn’t like more money...?” But research has found that more money actually isn’t always better; at least, it doesn’t always increase subjective wellbeing the way it appears to be doing so for financial advisors.

For instance, a study on income’s relationship with two aspects of subjective wellbeing – emotional wellbeing from enjoying everyday experiences (positive feelings in our study) and a life evaluation of how positive (or not) we consider our lives to be generally (life satisfaction in our study) – was conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton in 2010. In their general population study, they found that while increases in income were associated with increases in life evaluation (life satisfaction), there was a leveling off at about $75,000, above which there was no longer a continued increase in emotional wellbeing (positive feelings). By contrast, though, when it comes to financial advisors, there is a continued increase in wellbeing on both dimensions studied by Kahneman and Deaton – as income rises, so do both their life satisfaction and their positive feelings!

Advisor Wellbeing And Advisory Firm Revenue

Yet while our Kitces Research found that advisor wellbeing rises with income, we found that the same does not hold true when it comes to an advisor’s revenue. Obviously, to a large extent, it’s impossible to have a higher income without having the revenue to support that income. Yet, nonetheless, our research shows that once revenue crosses $1.5M, subjective wellbeing (combining together life satisfaction, positive feelings, and negative feelings) gets steadily worse as revenue continues to grow!

In fact, not only does wellbeing cease to rise above $1.5M of revenue, but by the time advisory firms reach $3.5M+ of revenue – typically associated with $500M+ of assets under management – advisor wellbeing is lower than it ever was, even in the earliest days when advisors have the fewest clients and least revenue and the most early stage growth stress!

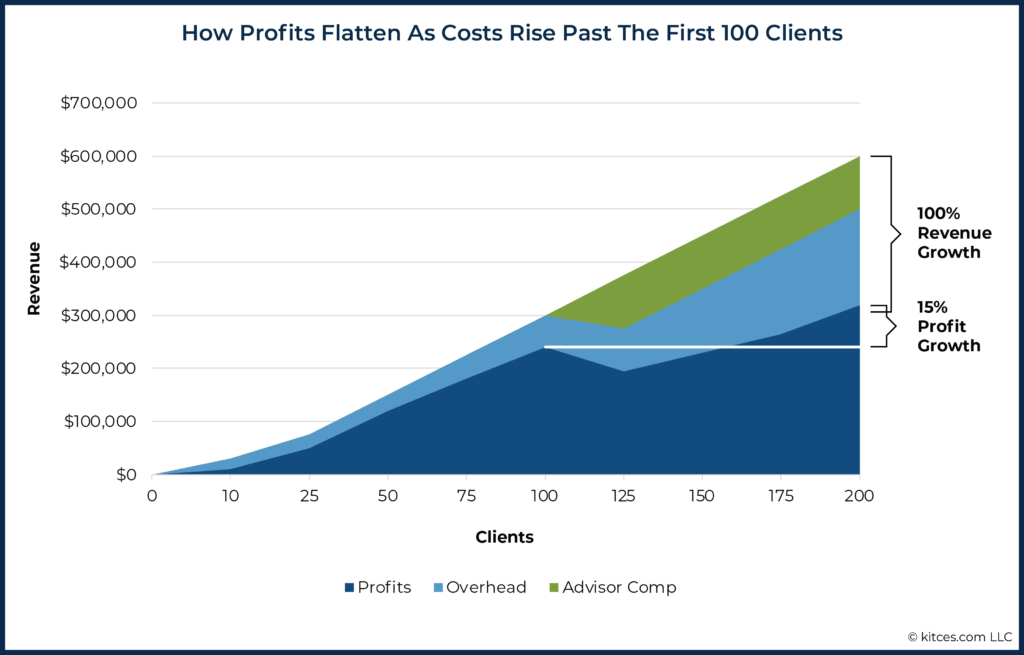

Or stated another way, while personal income has a positive relationship with increases in wellbeing, there comes a point where it takes so much additional work (in terms of growing and supporting revenue) to get only a little increase in income (because every 100 additional clients after the first 100 tend to be far less profitable) that the (emotional and satisfaction) costs are literally no longer worth the (wellbeing) benefits.

How Capacity Walls Impair Advisor Wellbeing (And Hiring Can Hurdle Them)

One of the fundamental challenges of growing an advisory firm is scaling the delivery and support of time-intensive advice relationships. After all, the average advisor at an independent RIA with financial planning relationships spends 5.4 hours/year in meetings with clients and 16.8 hours on direct client activity, and new financial planning clients are even more time-intensive with an average of 15 hours to complete the financial planning process and 34.5 hours spent in the first year of the financial planning relationship. Which means, simply put, that there are only so many clients that a financial advisor can service before they sheerly run out of time to take on more clients and grow their revenue further.

Advisory Firm Productivity And Revenue/Staff Ratios

Because of this time limitation and the number of clients that can be served with the available time, the reality is that firms can only generate ‘so much’ revenue from each client relationship. Accordingly, the traditional way to measure the productivity of an advisory firm is to look at the total revenue it services, and the total size of the team that services the revenue, to calculate the amount of revenue per staff member. Which, according to the latest 2020 InvestmentNews Pricing and Profitability survey of advisors, averages $275,000 of revenue per staff member.

In other words, the average advisory firm can support $275,000 of revenue with one person, but needs to add a second to go materially above that level. The second staff member expands capacity up to 2 × $275,000 = $550,000 of revenue, but at that point, the firm will again approach capacity, begin to run out of time, and struggle until it hires a third team member, which then expands capacity to 3 × $275,000 = $825,000 of revenue… at which point the firm will again hit a potential wall.

And when we delve further into the connection between the revenue of an advisory firm and the wellbeing of the advisor… those are the exact capacity walls that show up! As the chart below shows, a finer slicing of the data on advisor wellbeing shows that, as revenue grows to advisor capacity thresholds, wellbeing declines because the firm reaches its time-intensive capacity limitations… followed by a rebound in advisor wellbeing as staff are eventually added, and the capacity pressure is relieved to grow to the next tier.

In practice, these thresholds tend to correlate to the traditional growth of an advisory team itself, where the first hire is a client service administrator (by $275,000 of revenue) to support administrative tasks (because the advisor themselves is increasingly buried in scheduling and paperwork for a growing number of clients), the second hire is an associate advisor or paraplanner (by $550,000 of revenue) to support on the client’s financial planning tasks (as the volume of financial plan analyses and financial planning prep for meetings rises), and the third hire is additional administrative support (for the lead and associate advisors) to maximally leverage the team to its peak wellbeing approaching $1M of revenue.

Nerd Note:

The revenue/staff thresholds of the InvestmentNews study are tied to the average size of clients served by firms in the study – which was a very ‘healthy’ average of nearly $8,000 of revenue/client. As a result, another way to understand capacity limitations is that advisory firms hire an average of every $275,000 revenue/$8,000 revenue/client = approximately 35 clients. Accordingly, for firms that have lower revenue/client – e.g., their average client pays $4,000/year instead of $8,000/year – the firm will face capacity limitations approximately every $140,000 of revenue instead of every $275,000. If the firm provides less in services to their lower-revenue clients, this threshold may rise slightly – perhaps a hire every 45-50 clients or $180,000 – $200,000 of revenue. Because in the end, it’s not just the revenue that is the limitation, but the number of clients being served and the amount of service provided to each.

The key point, though, is that wellbeing doesn’t simply rise steadily as revenue rises because, on a day-to-day and month-to-month and quarter-to-quarter basis, it’s the capacity of the firm and the available time of the advisor (or the lack thereof as a capacity wall is approached) that drives advisor wellbeing.

The Management Burdens Of Multi-Advisor Firms

While the data shows that advisor wellbeing falls as it hits capacity walls and then rises once those walls are overcome with an expanded team, it is notable that advisor wellbeing peaks once revenue reaches the $1M to $1.5M range… and once it exceeds those levels, it declines and keeps declining as revenue grows and never recovers again.

So what’s different about capacity and hiring above the $1.5M revenue threshold versus all of the earlier thresholds where hiring through a capacity wall brought a subsequent lift in advisor wellbeing? The answer, in a word: management.

As while continued hiring of support staff – from client service administrators to paraplanners and associate advisors to trading/investment support – can scale up an advisory team, it can only go ‘so far’ before the advisor has to hire additional lead advisors to handle large swaths of clients. And at that point, the founding advisor’s role is no longer about meeting with and serving clients at all. It’s about managing other advisors to meet with and serve clients. For which the founding advisor must spend more time and receive (relatively) less incremental income.

Because, as noted earlier, every 100 clients that an advisory firm adds will never be nearly as profitable to the advisor as the first 100 were. As with the first 100 clients, the advisor earns both the profits of serving clients well and the implicit ‘salary’ of being the financial planner for those clients.

But with the next (and subsequent) 100 clients, it’s the next lead financial advisor who earns the bulk of the revenue by being ‘the advisor’ for those clients, while the founder only receives the net income after that advisor’s salary (and all of the other overhead costs and reinvestments into growing infrastructure that went along with it).

Nerd Note:

Most solo advisory firms don’t split their own income into the components of salary for work in the business and income for profits of the business. Nonetheless, their take-home income does contain an element of both. Which becomes very noticeable once the roles split, and a second/third/fourth advisor receives the “financial planner salary” portion of the income while the founder receives ‘only’ the profits.

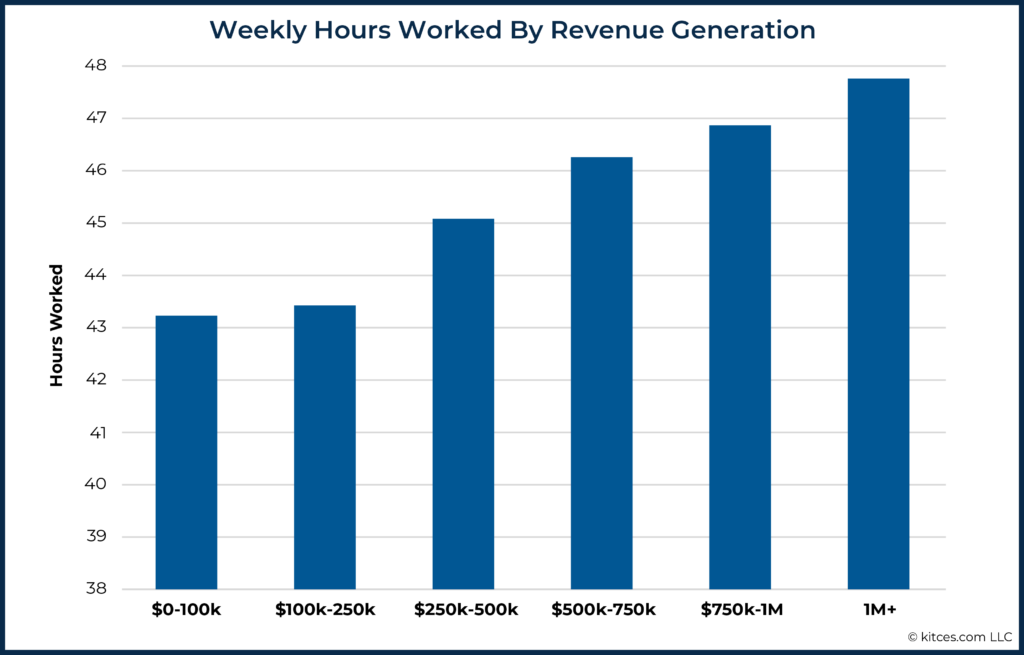

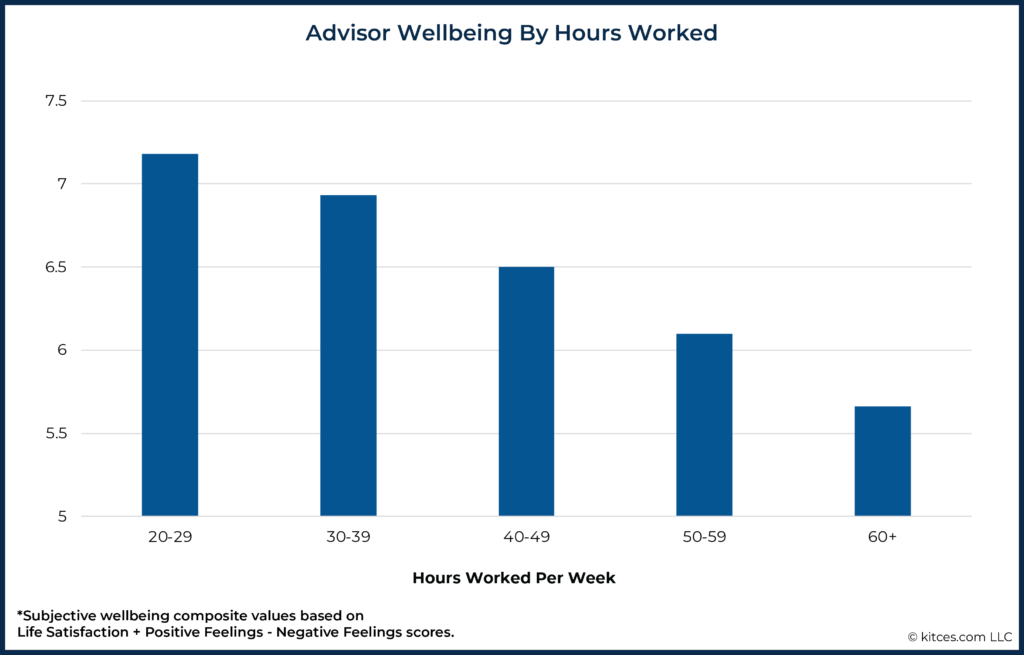

The end result of this phenomenon is that as the advisory firm grows, so too does the time it takes to manage an ever-growing number of team members. Especially since as the number of team members who must be managed increases, the advisor often still has to service their own clients as well, leading to a double-squeeze in managing more clients plus more staff at the same time. In fact, our Kitces Research on Financial Planning Process shows that the number of hours that financial advisors work rises almost inexorably as revenue rises as well.

This ongoing squeeze in time between client duties and management duties, in turn, often leads advisory firm owners to scale back on the number of clients they’re serving in order to free up more time for team management. Which can help grow the firm to the next level. But which also means the founding advisor is spending less and less time serving clients… the one thing that they most wanted to do when they started the firm!

All of which helps to explain why the lowest levels of wellbeing emerge at the highest levels of revenue. Because the job the advisors once loved (being a financial advisor) and were probably great at (which is why they were able to build such a large practice) is no longer the job that they do! They no longer manage (many or any) clients, and instead manage staff and business budgets.

And this change in role, the somewhat inevitable result of growing ever-higher revenues, has a negative relationship with wellbeing. The personal gratification gleaned from those close relationships with clients, and even the way financial planners may have been able to structure their day around clients, is now gone, and that is a difficult and often unmotivating, possibly fairly unfulfilling position to be in, especially when the income for doing this work that you do not love does not grow nearly as much for all the additional work being done!

Maximizing Advisor Wellbeing By Maximizing Profitability Over Just Revenue

So given these dynamics of advisor income, revenue, and wellbeing, what should advisors do to maximize not just their income and/or revenue, but the wellbeing they derive from them… because, in the end, revenue and income and wealth are typically the means to some end that brings us happiness, satisfaction, and wellbeing! Which means that by focusing on wellbeing itself, we can potentially shortcut the pathway to maximizing our happiness!

Hiring Ahead Of Capacity Walls To Manage The Advisor’s Time

First and foremost, since it is clear that wellbeing does decline when advisors hit capacity walls that drive up their stress and working hours in the business, it is crucial to be aware of one’s own capacity to serve clients.

Advisory firms typically hire a new team member for support every 35-50 clients, which, based on the average revenue of each client (which varies by firm), may be a hire anywhere from every $150,000 to $250,000 to $350,000 of revenue. And advisors who wait too long risk facing a ‘double-whammy’ of being overwhelmed by the number of clients and the time it takes to service them, and that taking the time to hire and train a new team member will just bury them even further, even though it’s essential to get past the wall.

The issue is even more important for advisory firms in their earlier stages of growth because such firms have a higher percentage of clients who are still in their first (and even-more-time-intensive) year. Which means that while firms that are mostly in ‘maintenance mode’ with existing clients may be able to handle closer to 50 clients/team member, those that are actively and rapidly growing are much more likely to hit the wall closer to every 35 clients (or even in the 25-35 client range). For which, again, hiring before capacity is already reached – so there’s time to hire and train – is crucial to avoid the decline in wellbeing that comes from hitting the capacity wall.

Said another way, advisors who focus on their own self-care are not selfish. No one advisor can do everything, and focusing time and energy as an advisor on the things that feel great and rewarding are crucial not only to drive future growth but also to maintain wellbeing on the journey itself. Especially given that, as the data shows, not everyone needs a mega-practice to be happy. Instead, the average advisor who grows to a multi-advisor firm never regains the wellbeing they achieved as a highly profitable solo!

Maximizing Happiness By Maximizing Revenue Per Client

While financial advisors can only ever serve ‘so many’ clients before running out of time (as it still takes a substantive amount of time to do all the client work and have the client meetings, and technology can only do so much to shortcut a client’s need for face-to-face conversations), wellbeing itself is still driven heavily by advisor income. Thus, the most straightforward way to increase advisor wellbeing is to generate more revenue per client.

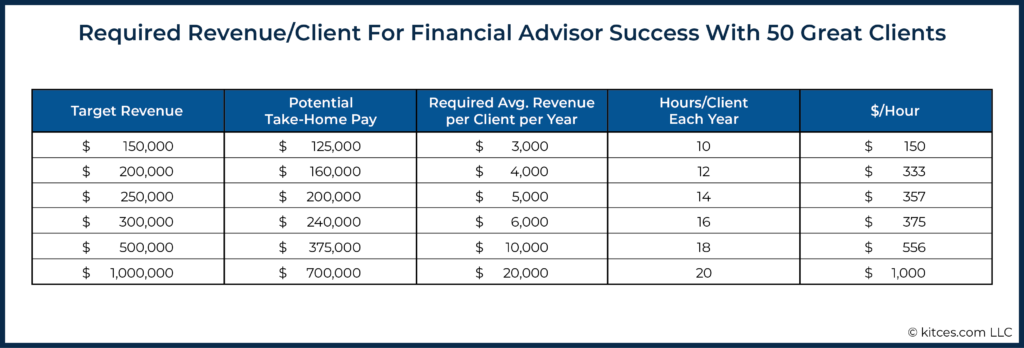

After all, advisors who generate a very high amount of revenue from each client simply don’t need very many clients to reach their income goals. Alternatively, generating a high level of revenue/client allows the advisor to have a higher ceiling on ‘maximizing’ income they can earn while still being an advisor (and not being compelled to make the shift to being a multi-advisor manager instead).

Thus, for instance, instead of simply focusing on how to forever grow the advisory firm's practice and add more revenue and more clients (and more staff to support them), consider the advisory firm that sets a concrete goal to work with ‘just’ 50 great clients. Once a limitation to the total number of clients is set, the only way to grow is to increase the revenue per client. The more each client pays, the more the advisor can earn… without necessarily increasing staff!

Of course, working with clients who pay higher fees does often entail doing at least some additional work with them, and the total hours per year in client service are typically higher for clients who pay more. Nonetheless, because many of the ‘foundational’ elements around clients – meeting with them, preparing for meetings, taking the time to get to know them, etc. – is similar for all clients, more affluent clients typically end out paying a significantly higher revenue for each hour of advisor work. And with only 50 great clients, even top-tier clients that add up to 20 hours/year of work still amounts to only 1,000 client-facing hours per year with 50 clients… or an average of barely 20 hours/week to generate $1,000,000 of revenue and $700,000+ of take-home income?!

Which in turn means figuring out how to reach more affluent prospects who have higher-stakes problems (for which they will pay greater fees), and reinvesting into the advisor’s own expertise to be able to command a higher hourly fee (whether billed by the hour, or as an hourly equivalent for a subscription fee or AUM client who still has to get a certain number of hours of service and expertise to attract and retain the client).

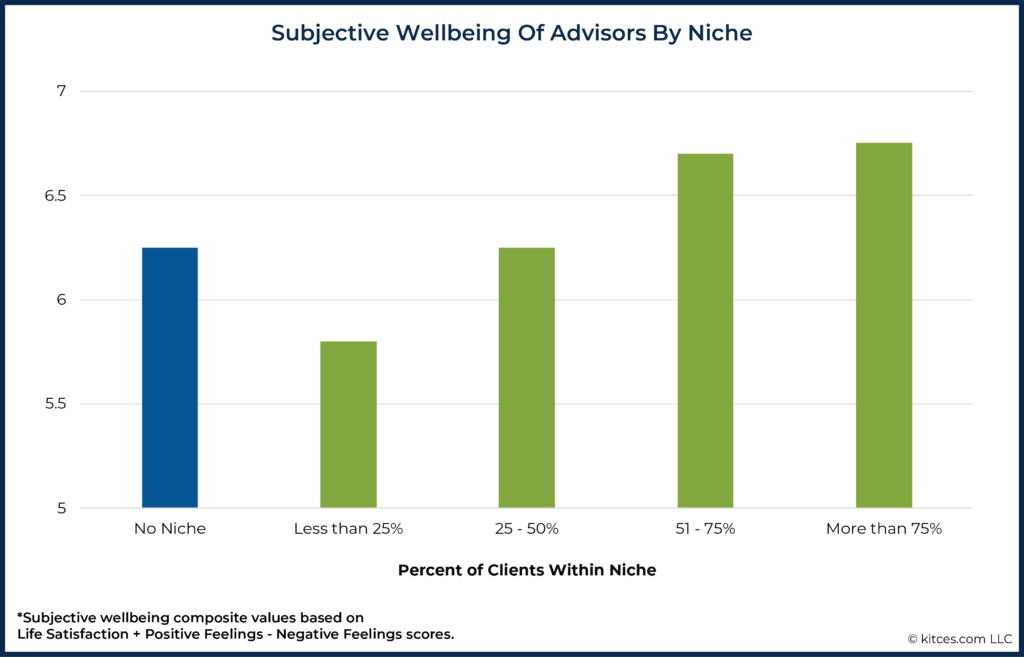

Accordingly, it is perhaps not surprising that our Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing also shows that advisors who focus on a niche ultimately experience greater wellbeing, as a niche focus (whether by pursuing a particular profession, psychosocial demographic, or experiential offering) provides the level of differentiation and specialized expertise to be able to command higher fees.

Notably, though, transitioning into a niche – and the messy process of crafting expertise and formulating one’s differentiation – is still stressful, as advisors with a declared niche but with fewer clients in their niche (yet!?) experienced lower wellbeing. Once established, though, advisors with a niche who had the majority of their clients in their niche experienced greater wellbeing as they commanded higher fees that allowed them to generate their desired revenue from fewer clients (while also enjoying the time efficiencies that come from more standardized processes with a more consistent niche clientele).

Getting Clear On Your Vision… And Going After It

While some of the above examples may be somewhat extreme to many advisors – not everyone can attract and serve clients who all pay at least $20,000/year and compensate the advisor at $1,000/hour for every hour of work they do – the point remains: when advisors have a fixed capacity in the number of clients who can be served (whether it’s 50 great clients, or 75, or a physiologically-defined maximum capacity of 100), and adding more advisors adds management burdens that may not be desirable, increasing the revenue per client is the key path for growth in both income and wellbeing.

In practice, established advisors who have already grown past this point and have ‘too many’ clients (and/or ‘too many’ team members to manage) may face hard decisions of their own. One option is to consider “rightsizing” the practice to fewer clients, carving off the lower segment of clients (that impair capacity while dragging down per-client profitability) by either selling that portion of the business to another advisor (who has more capacity to serve them) or even ‘spinning off’ an existing advisor who serves those clients so the founder can re-focus on their core clientele and serving them (and giving up what may be a little bit of income but a lot of management headache in the process!).

Alternatively, other advisors may prefer a more gradual “1-in-1-out” approach of only adding above-average clients by simultaneously referring out a below-average client. For advisors with far too many clients, a “1-in-2-out” approach may even be necessary. For instance, for every $5,000/year client the firm takes in, it transitions out, refers out, or ‘graduates’ two clients who were paying $2,500/year or less. Which means the firm ends out with similar net revenue – with $5,000 in and 2 x $2,500 = $5,000 out – but with fewer clients to serve thereafter. Which, repeatedly done over time, can substantially lift the advisor’s revenue/hour and reduce their client load and hours worked for the same income, lifting advisor wellbeing in the process.

As in the end, our own Kitces Research shows that the key predictor of advisor wellbeing is really just driven by how many hours the advisor has to work to generate their desired income!

Which means for those who haven’t yet grown to the point that they reach this “capacity crossroads” (and have to either hire more advisors onto the team or begin the 1-in-1-out process), it’s all the more important to get a clear vision on what that future vision of growth will be, whether to operate as a highly profitable solo advisor, as a multi-advisor boutique, or to try to build a scaled advice enterprise.

For those who are uncertain what path to pursue, it can be worthwhile to think about the things that arouse happiness or the varied job roles that are most enjoyable. If an advisor realizes that they love being a manager and a trainer – great! They might benefit from moving further into that role and releasing more of their core group of clients to other financial planners in the firm.

However, if this doesn’t apply, advisors should recognize that, that is ‘okay’ and that there are still opportunities to change and take control of future outcomes. Downsizing, or rightsizing, the practice back to a level of revenue, personal income, and client work can help some advisors feel valued and fulfilled. Advisors who still want to grow might consider hiring a CEO or partnering with another financial planner who does love the management side of things, allowing them to go back to the more enjoyable client work.

Because in the end, we all have our own motivators from which we derive our happiness and wellbeing. The real key to success is not to follow any one specific prescription for success. It’s to get clear on our own definition… and then focus relentlessly on pursuing that vision.

Ultimately, the good news is that our Kitces Research on Advisor Wellbeing shows that advisors overall are experiencing fairly high levels of wellbeing.

Yet, this is not without caveats and nuances mostly related to capacity. Advisors are not happy when they have too many clients to manage, burdened either because they don’t have proper staff support (as they hit the hiring milestones every 35-50 clients on the path to full capacity) or because they have too much staff support that they’re responsible for managing as the firm becomes multi-advisor (taking time away from the clients they first set out to serve).

The good news is that these capacity setbacks are relatively predictable and do not have to be permanent states of discomfort. Advisors can actively plan for new hires and be mindful of their own capacity before things get too out of hand. And advisors can and should have the wherewithal to reflect where they are (or are not) operating at their best, or where they do (or don’t) enjoy spending their time… and make a change if necessary.

In other words, our wellbeing is in our own hands, and as advisors, we have a remarkable level of control. But it’s up to each individual to take control and use the capabilities we have to make our advisory firms what we ultimately want them to be as fulfilling places to work!