Executive Summary

Loss is an experience that all humans share at one point or another, and when a loved one dies, the grief is undeniably and devastatingly certain. But what about the grief that we might feel for a loved one who is still alive, only physically separated from us? Or for one who is mentally incapacitated, but who no longer has the capacity to recognize us? These feelings of grief for someone who is still alive, but no longer present (either physically or psychologically), are referred to as ‘ambiguous loss’. For example, some clients might have relatives who are no longer mentally lucid (psychological ambiguous loss), and some may have loved ones who need full-time care provided by an assisted living facility (physical ambiguous loss). And as would be expected with extended human lifespans and increasing cases of mental incapacity that comes with a growing, older population, feelings of ambiguous loss are on the rise.

Because the average human lifespan has increased over the last several decades, we are now at a point where family members are commonly expected to take on the responsibility of caring for elderly parents or spouses, many of whom are afflicted with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and dementia. Accordingly, advisors may find themselves dealing with clients suffering from ambiguous loss, especially when conversations are raised around incapacity planning and estate planning.

While most financial advisors don’t have formal training in grief management, there are some basic guidelines that can be effective in working with clients suffering from ambiguous loss. As a starting point, mentally preparing for client conversations, for example, can include a series of questions that advisors ask themselves about their own personal attitudes around grief and loss in general, and also around understanding the situational causes of their clients’ ambiguous loss. Understanding the daily routines and relationships that the client may be struggling with can also help the advisor relate more empathetically with the client. And starting any incapacity discussion as early as possible to give clients ample time to process their feelings of ambiguous loss while adjusting to their new responsibilities can prove helpful for the client to transition through change.

Additionally, the advisor can support clients by acknowledging their feelings of ambiguous loss, and helping them adjust to the ambiguity they face by planning for a broad range of financial scenarios. This can help clients attain a level of certainty over what they have control over versus what variables in their situation will inevitably remain unknown, and that may eventually need to be addressed. And last, the advisor can play an important role in their client’s life by helping them through the difficult process of understanding and accepting what is happening to them, by simply giving them time and space to share their stories when they are ready to do so.

Ultimately, the key point is that ambiguous loss is commonly experienced by many people, and advisors should be prepared to work with clients and their issues in a sensitive yet productive manner. The conversations will be difficult and may be highly charged with emotion, but offering compassion and providing support can have a huge impact on the client’s ability to make sound financial decisions, as well as establish trusting relationships not only between the advisor and the client, but with the client’s support system as well.

With the average age for wealth management clients at 62 and rising, the prevalence of degenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) is on the rise as well. In fact, the CDC reports the number of Americans with Alzheimer’s will nearly triple by 2060. And as a result, incapacity planning is increasingly becoming a crucial aspect of any financial planning engagement.

When dealing with incapacity planning issues with clients, financial advisors will not only need to understand the technical aspects of planning for incapacity, but will also need to be prepared to face the emotional, behavioral, psychological, and relational aspects of later-in-life planning.

Fortunately, the technical skills needed to address incapacity planning are often covered through academic programs and continuing education. However, interpersonal skills necessary to address the human side of incapacity planning are often learned via trial and error throughout an advisor’s career. And no client necessarily wants to be the guinea pig while the advisor is learning how to handle such situations. Especially considering that during incapacity planning, clients are being asked to think through (or deal with in real time) very unpleasant scenarios, and potentially acknowledge aspects of their family dynamics that they would rather not address.

Accordingly, advisors need to be familiar with some of the unique issues that arise from the client communication perspective when dealing with incapacity planning for clients, such as the concept of ‘Ambiguous Loss’.

Ambiguous Loss – Grieving For Someone Who Hasn’t Passed Away Yet (But Is No Longer Present)

When a client becomes incapacitated, there are unique planning challenges that need to be addressed, along with unique feelings of loss for those around the client. As, even if the incapacitated individual hasn’t passed away, when the lines between presence and absence are blurred, a form of ‘ambiguous loss’ can emerge.

One version of ambiguous loss is ‘physical’, felt for a person who is physically absent, yet psychologically present. For instance, when a spouse initially moves into a care facility, they are no longer present in the home or around all of the time. But they will often still be top-of-mind – thus still psychologically present – for those still at home.

The impact of this physical form of ambiguous loss is significant. It could manifest as a spouse continuing to reserve the head of the table for their absent partner, or even refusing to downsize into a smaller home because they still feel they need the space for the two of them (as psychologically, the other partner isn’t truly ‘absent’, even though they’re physically no longer in the home). It is also worth noting that this form of ambiguous loss can be found in many non-incapacity-planning scenarios as well (e.g., a family with a child away at college, or with a parent on military deployment).

Another version of ambiguous loss occurs when a person is psychologically absent, but physically present. A common example of the psychological form of ambiguous loss can be seen in dementia. The person may be physically present, but psychologically is becoming removed from the family. It is a period where a family may even be mourning for the loss of their family member experiencing dementia, even though that person is still physically alive.

Psychological ambiguous loss can also be related to more abstract feelings of loss, which can often be seen in incapacity planning. For instance, a client who has recently been diagnosed with dementia or perhaps just knows that dementia runs in their family may be actively mourning even if they are currently experiencing few or no effects of the disease. A client may also begin mourning the loss of their youth, mobility, freedom, and/or health when encouraged to create an estate plan or address future incapacity even if they won’t lose these aspects of their lives for a long time.

The Impact That Ambiguous Loss Has On (Financial) Decision-Making

Ambiguous loss can have both personal and relational impacts that may even disrupt effective incapacity planning itself – not to mention being uncomfortable to discuss for clients and the financial advisor.

For instance, the concept of ambiguous loss, and the difficulty of implicitly thinking about how such losses might play out in the future, helps to explain the low rates of clients actually putting together estate plans. Thinking about death is not something most people enjoy, or have any interest in doing without some significant prompting. Moreover, incapacity planning may be even more difficult, as it involves contemplating not only death, but the possibility of becoming immobilized and losing one’s self, which can be incredibly scary (to the point that ambiguous loss fears debilitate the incapacity planning process).

In essence, the presence of ambiguous loss can have an immobilizing effect that makes it difficult for families to make decisions. Thus, the more acute the ambiguous loss potential – which is particularly common with incapacity planning – the more difficult a hurdle it becomes. And consequently, it is important to think about the implied loss that incapacity planning may raise along with a client’s possible reactions.

For instance, an advisor could look at incapacity planning through the lens of the individuals facing their own potential future incapacity. For those individuals facing Alzheimer’s or dementia, it is common to feel hopelessness, helplessness, anger, and exhaustion. They may not only be afraid of the changes they will ultimately endure, but may also despair over their diminishing ability to perform tasks for which they are responsible, like managing household finances, or to enjoy hobbies, such as playing a musical instrument.

Alternatively, an advisor could look at incapacity planning through the lens of the impact on the key relationship dynamics for the client. Ambiguous loss can cause family conflict, mistrust of authority figures, and anger with professionals, which can complicate the incapacity planning discussion and bring up several complex emotions within a family.

For instance, when creating a will or planning for a healthcare power of attorney, a client may be re-living the loss of the relationship with an estranged child. Clients could also be grieving over more abstract situations, like the misperceived loss of their youth or freedom (even though they are still young and in good health, because the planning process forces them to think about a time when those will be gone). Thus, a client may be completely put off by the mention of establishing an incapacity plan, because they do not want to think of themselves as elderly or in a state of dependence.

Difficulties with ambiguous loss can be especially challenging for clients that are accustomed to being in control, and who see this as a central identity in their lives. In such instances, an advisor could unknowingly unearth a client’s deepest fears, regrets, and insecurities, all by simply attempting to provide the best financial planning recommendations possible to address an unaddressed need for incapacity planning. The end result may even be clients expressing anger and mistrust of the advisor, that seemingly arise out of nowhere.

From the client’s perspective, those experiencing unrecognized ambiguous loss can often attribute the unsettling feelings that have arisen from their planning session to a belief that they’ve received ‘improper’ recommendations from the advisor or that the advisor is insensitive, and may even accuse the advisor of having another hidden agenda. As financial planning is a relationship-driven practice, a loss of trust that develops between an advisor and client from not properly anticipating an ambiguous loss scenario could pose a major setback, not only for setting up proper incapacity planning, but also for maintaining a strong relationship with the client in general.

What Advisors Can Do To Help Clients Struggling With Ambiguous Loss

Given all of these potential (and common) scenarios where ambiguous loss may arise, the good news is that there are ways for advisors to confront and get through these tough conversations, which support clients and ultimately help them to avoid potentially neglecting to make crucial financial planning decisions.

For instance, “Financial Planning with Ambiguous Loss from Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications, Applications, and Interventions” by Shelitha Smodic, Emily Forst, John Rauschenberger, and Megan McCoy in the Journal of Financial Planning proposes methods to make these interactions easier for advisors, by adapting the intervention methods of noted ambiguous loss pioneer and researcher Pauline Boss to a financial planning practice.

Accordingly, some simple steps from Smodic, et al. to prepare for incapacity planning conversations with clients who may be dealing with ambiguous loss include:

Step 1: Mentally prepare yourself (as the advisor) for the conversation before talking to the client.

As discussed throughout this blog, conversations about incapacity can (and often do) get emotional, and may cause clients to behave in some unusual ways.

As such, this first step is for the advisor to prepare themselves to be non-reactionary. Not that it’s good to be an emotionless robot, but it is important for the advisor to be mindful that they do not say anything that could make the situation worse or even scarier than it already is.

Because the situation doesn’t necessarily come up often for advisors, one way to ‘practice’ and become better able to confront these issues is to consider the following introspective questions to get into the right frame of mind (and heart) to work with clients that may face an ambiguous loss scenario.

Acknowledge your own relationship with these types of conversations and situations (high-emotion and high-stress).

- What do I know about this diagnosis and its symptoms?

- What are my biases – does crying make me uncomfortable, do death and dying conversations make me nervous, how do I react to anger or fear?

- What is my comfort level with these types of discussions?

- What is my personal history with incapacity planning?

Think through the unique hurdles your client may face in this conversation.

- Do you know of any specific pain points for this client? (e.g., recent death of spouse or child, parent that suffered from dementia)

- What are the family dynamics?

- Have you met the future caregivers for this client?

- If children are involved, how is the client’s relationship with them?

- Does the client have a strong social support system?

- How has your client reacted to stress or grief in the past?

Finally, if you have access, you may also want to review any estate planning documents. There is a lot of information about family dynamics and personal values that can be gleaned from this information, even if it is older or has gone through a number of iterations.

Step 2: Start the incapacity discussion early.

Once you know how you feel and think through any potential biases, it is time to talk to the client, and talking to them sooner rather than later is best. Starting the discussion about incapacity early not only provides major value by allowing sufficient time for planning itself, but it also allows clients time to sit with the potential issues and emotions that may arise that they need to face before they’re ready to actually make some choices about what to do.

For instance, starting the conversation early would allow the advisor to establish relationships with future caregivers (e.g., by starting to incorporate adult children in family meetings). This can help make the future transitions of responsibilities less stark, and cut down on later trust issues. It may also feel empowering for the individual entering into the caregiving role to feel comfortable with the support system (that now includes the financial advisor), which has been built to assist them.

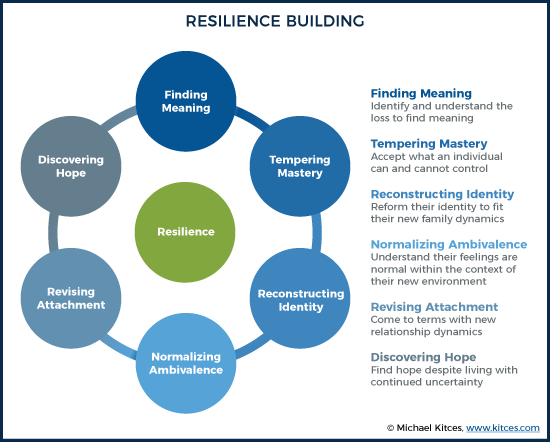

Step 3: Help the client gain comfort with ambiguity.

Planning is indeed important, but as financial advisors know, things do not always go according to plan. As such, it is important to discuss change and to acknowledge it as part of the process.

A great way to do this in practice is to run multiple financial scenarios. Help clients to establish plans A through D, not just plan A. As part of this multiple-scenario process, it is also helpful to discuss what can be planned and controlled for, versus what cannot be planned or controlled for. For instance, advisors and families can plan for who will care for them and what that might look like, but advisors and families may not be able to prepare for how quickly the disease progresses.

Step 4: Help the client find meaning.

When facing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, it is common to lose one’s sense of self. For instance, the individual may have been the person taking care of the finances, but may no longer be able to carry on in this role, and may have new fears or thoughts not only about losing the role but wondering who and how it will be taken on. A spouse may struggle to plan for their own goals and dreams outside of caregiving or be overwhelmed by the sense of ambiguous loss of their life partner. Similarly, a child caregiver may struggle with the increased responsibilities they must take on and may find it difficult to cope with the changing dynamic of being cared for to being a caregiver.

As such, it can be very healing (and helpful to planning) if you create the time and space for the individual and family to share their story when they are ready to do so. Encourage clients to stay connected and plan not only for future caregiving needs, disability, and death, but their other areas of personal fulfillment.

There are many methods that financial planners can use to create time and space for clients during these challenging times. Simply blocking off extra time during an already scheduled meeting to check in with a caregiver or an individual can ensure that the financial advisor has the time to let clients more fully express themselves and can avoid rushing a potentially emotional client out the door. If the client is interested, a financial planner could also prepare a more interactive meeting where perhaps a facilitator or a mental health professional is present with family members and the financial planner. In these types of meetings, the family can go through exercises and discussions that open the lines of communication about the estate plan, and do positive things like developing a family financial motto and discussing future goals. A financial planning firm could also host a client event where a subject matter expert in caregiving presents to the group, which could bring together a community of clients that are having similar experiences and challenges.

The most important thing about creating time and space is that the financial planner normalizes the meetings and conversations. Financial planners may state explicitly that they have blocked off extra time because it is common for these conversations to become emotional, and to also let the client know that whatever comes up is okay. If you want to take a more active role and take the client and their family through activities and practices, consider offering these interactive meetings and seminars in your marketing or at the very least make all clients aware of it as an option and talk about what to expect (even clients that do not experience ambiguous loss have a tough time with estate planning and may enjoy the interactive process).

Step 5: Instill hope.

Hope can come in many forms. Again, clients may be very scared or nervous about giving up their role as the financial person or primary decisionmaker in the family, or even just thinking about the fact that it may happen in the future.

In such situations, you can offer the perfect place to give hope. We are planning for all of the worst scenarios, but this is so we have a plan and a solid support system in place no matter what issues arise in the future. You can let the family know that you are there for support, to teach and guide them and their future caregivers through the many financial decisions and transitions ahead. You can also instill hope by demonstrating, through the creation of the plan, that an individual’s legacy or own hopes, like charitable giving or college planning for grandchildren, will be documented and carried out.

Until the medical world finds a cure for some of the most frightening diseases out there, financial advisors are likely to work with clients experiencing ambiguous loss driven by dementia. For clients who are experiencing ambiguous loss or are in a situation where they may soon be facing it, financial advisors can be valuable resources to support families during these challenging times. The key for advisors is to be aware of the issues, both social and emotional, that are tied to ambiguous loss, which can help them provide the empathy and emotional support that may ultimately be the difference for their clients in preparing and planning for incapacity as effectively as possible.