Executive Summary

For the past several decades, asset allocation has been the cornerstone of portfolio design, with a focus on diversification and the addition of non-correlated investments to the portfolio to reduce overall volatility and improve risk-adjusted returns. This trend has been accelerated in recent years, as weak returns in both bonds and stocks have helped to fuel a drive towards "alternative" investments that further increase the intended diversification and the number of asset classes in the portfolio.

Yet running in parallel with this trend has been the rise of various types of tax-preferenced accounts, with first the IRA and 401(k) and more recently the Roth IRA and Roth 401(k), in addition to the ongoing presence of tax-deferred annuities and the standard taxable brokerage account. As a result, a new challenge is beginning to emerge: the question becomes not only which asset classes should be owned and in what amounts, but also where should those asset classes be held? In other words, it's not just about allocation of the assets to build a diversified portfolio now, but also about the locations in which to place those diversified investments.

Given that recent research has shown effective asset location strategies can add 20-50+ basis points of "free" value to annual returns, providing guidance on asset location is becoming increasingly popular. Yet unfortunately, asset location strategies are often dominated by myths and misperceptions! Ultimately, the reality is that good asset location decisions actually should be influenced by both the tax efficiency of investments and also their expected returns, which makes the analysis somewhat more complex... but also reveals why in today's environment most bonds actually should NOT go into tax-deferred accounts!

Basics of Asset Location Strategies For Portfolio Management

In a simplified two asset class portfolio, the principles of asset location are relatively straightforward. Assume the following scenario as a baseline: the client has $500,000 in a taxable account and $500,000 in an IRA, and intends to implement a 50/50 stock/bond asset allocation. Given a total net worth, this means the client will end out with $500,000 in bonds and $500,000 in stocks, and thus has to make a decision whether to put the bonds in the IRA and the stocks in the taxable account, or to hold them the other way around. If we make some simplified tax assumptions - that the bonds generate a long-term average return of 5% and are taxed at a 25% ordinary tax rate, and that the stocks generate a long-term average return of 10% taxed at a 15% long-term capital gains tax rate, and that both investments are bought and held for 30 years (no turnover in the intervening time period), then the two alternatives produce the following wealth results (ignoring rebalancing for the time being):

Bonds held in taxable account and stocks in the IRA: Bonds grow at a 3.75% after-tax growth rate (5% gross returns less 25% taxation), for a total future after-tax value of $500,000 x 1.0375^30 = $1,508,736. Stocks grow at a gross return of 10% for 30 years, but are then fully taxable when withdrawn from the IRA (still assuming a 25% tax rate), resulting in a final after-tax value of ($500,000 x 1.10^30) x (1-0.25) = $6,543,526. Total after-tax wealth is $8,052,262.

Stocks held in taxable account and bonds in the IRA: Bonds grow at a 5% gross return, but then are fully taxable at the time of IRA withdrawal, for a future after-tax value of ($500,000 x 1.05^30) x (1-0.25) = $1,620,728. Stocks grow at a gross return of 10% for 30 years, and the growth is then taxable at a 15% long-term capital gains tax rate, resulting in a gross value of ($500,000 x 1.10^30) = $8,724,701, $a tax liability of ($8.724,701 - $500,000) x (0.15) = $1,233,705, and a final after-tax value of $8,724,701 - $1,233,705 = $7,490,996. Total after-tax wealth is $9,111,724.

As the scenarios above illustrate, in the base case it's more appealing to put bonds in the IRA and stocks in the taxable account, due primarily to the benefit of having the growth in equities taxed at preferential long-term capital gains rates instead of ordinary income (stocks in the taxable account finish with a value of $7,490,996 instead of only $6,543,526), and the added bonus of allowing bonds that would otherwise be fully taxable annually (resulting in an ongoing tax drag to compounding growth) to instead accrue tax-deferred and just be taxed once at the end (bonds in the IRA finish with a value of $1,620,728 instead of only $1,508,736 when held in the taxable account).

The Importance Of Tax Efficiency

The biggest caveat of the simple asset location scenario indicated above is that it assumes that bonds are maximally tax-inefficient (where all growth is fully taxable annually as ordinary income), while stocks are maximally tax-efficient (where all growth is only taxed once, at the end of the scenario). In practice, though, this is rarely the case, both because most equities generate a portion of their long-term growth via dividends (which are taxable when received, albeit at favorable long-term capital gains rates due to qualified dividend treatment), and also because even buy-and-hold portfolios ultimately experience some turnover, whether because available investment options change (e.g., a better/lower cost index) or simply due to rebalancing over time (notably, the portfolios above that started out as 50/50 did not end 50/50 due to asset allocation equity drift from the higher returns on stocks).

The reason that tax inefficiency matters is that over long periods of time, the benefits of tax deferral for inefficient investments can even trump the preferential rates we apply to long-term capital gains (and qualified dividends). For instance, with the aforementioned portfolio where bonds are in the IRA and the stocks are in the taxable account to take advantage of favorable capital gains rates, assume instead that the stocks growing at a 10% average annual rate are annually taxable at 15% qualified dividend and long-term capital gains rates; as a result, stocks only grow at a net effective ongoing rate of 8.5%/year after-tax. With these assumptions, the future after-tax value in 30 years is only ($500,000 x 1.085^30) = $5,779,126 for the stocks; when added to the $1,620,728 future value of the bonds held in the IRA, the total value is only $7,399,854.

When compared back to the earlier examples, a startling result appears: even with ongoing taxation at favorable 15% rates, the tax-inefficient stocks in the brokerage account (with bonds in the IRA) actually produces less wealth (only $7,399,854 remaining) than holding the stocks in the IRA (at $8,052,262)! Yes, the stocks in the latter are ultimately taxed at higher rates, but only after three decades of tax-deferred growth! And of course, the reality is that the stocks could even be less tax efficient than the example shown here; after all, more actively managed equity strategies could include some short-term capital gains turnover at ordinary income tax rates as well, which would result in even less final after-tax wealth by holding stocks in the brokerage account and bonds in the IRA!

The Complications Of Additional Asset Classes

Another caveat of the examples above is that in the real world, most clients own more than just two asset classes, and certainly more than just two individual investment positions. The inclusion of additional investments, each of which may have their own investment characteristics, including varying tax treatment and efficiency (between long-term capital gains, short-term capital gains, qualified dividends, non-qualified dividends, and taxable interest), makes the analysis far more complex. To really determine which asset location strategy is "optimal" would include a large number of calculations for various permutations; while holding two investments can be done with a simple scenario A vs scenario B, with 10+ different investments the analysis could potentially require dozens of comparison scenarios.

In addition, the reality is that not all clients have a precisely equal division of wealth between taxable and retirement accounts in the first place; clients may have more or less money in retirement versus taxable accounts depending on their prior circumstances, and as a result the optimal asset location may begin to shift from one client to the next simply because some clients have more IRA dollars than others. (Of course, the process is even further complicated by the fact that different clients may have different tax rates, which can also impact the relative benefits of putting various asset classes into one account or the other.)

As a result of the complexity of additional asset classes, and the limitations of how much money happens to be available in retirement versus taxable accounts, the most effective process to determine asset location shifts. Instead of trying to calculate every possible permutation of investments in various accounts to see which results in the greatest projected wealth, the best strategy instead is to focus on which investments create the most benefit by either being held in the IRA (because they're extremely tax inefficient) or being held in the taxable account (because they're very tax efficient), and prioritize the placement of those investments accordingly.

For instance, a high-turnover equity fund (lots of short-term capital gains), a very tax-inefficient income REIT (significant amounts of taxable distributions treated as ordinary income), and a global equity-income fund (with high-dividend foreign stocks not eligible for qualified dividend treatment) might have priority in the retirement accounts. Conversely, a large core position in the S&P 500 index that will be bought and held with no turnover might have priority in the taxable account. Accordingly, a client who only had $100,000 of IRA funds and $900,000 of taxable assets would fill the IRA quickly with some of the most-tax-inefficient investments, and "everything else" would end out in the taxable account; conversely, a client who only had $100,000 of taxable assets and the remaining $900,000 in retirement accounts would fill the taxable account with the high priority S&P 500 index fund, and "everything else" would end out in the IRA.

By following a "prioritization" process, it's easier to know which investments to place in which accounts for a particular client, without needing to calculate the results of every possible combination of investments allocated into each type of account, done separately for every client who has a different balance of taxable and retirement account assets.

The Final Driver Of Asset Location Prioritization: Expected Return

In order to create a proper list of asset location preferences for a list of investments, there is one more key factor to evaluate: the expected return of the investment. It's not enough to simply know the potential tax rates that will apply to an investment and its tax efficiency (or inefficiency); after all, if the reality is that the expected return is very low, there's simply not much benefit to tax deferral in the first place. Avoiding the consequences of tax drag just doesn't matter very much when there's not much return to compound in the first place.

For instance, if an investment is taxed at 25% ordinary income tax rates, but only earns 2% growth rates, the value of growing $100,000 for 30 years and then having all the growth taxed at ordinary income rates is $160,852, while the value of just growing at 1.5% after-tax (i.e., having the taxes applied annually) is $156,308. The difference is a mere $4,544. On the other hand, in the same scenario where the gross rate of return is 6%, the difference between 30 years of tax-deferred growth (6% compounded for 30 years and then taxed at 25%) versus growing annually at just 4.5% net (with annual taxation) is $455,762 vs $374,532 or a difference of $81,230. Simply put: effective asset location decisions matter exponentially more for high-return investments than low-return investments.

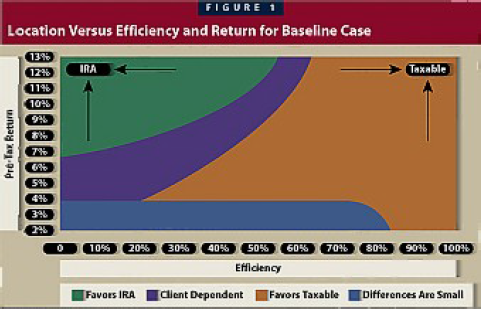

Accordingly, the chart below, from "Asset Location: A Generic Framework for Maximizing After-Tax Wealth" by Gobind Daryanani and Chris Cordaro in the January 2005 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning may represent the single most important chart in the asset location decision: finding the trade-offs where it's better to lean towards the IRA or taxable account based on both the tax efficiency (the X axis) and the expected return (the Y axis). Note in particular the zone of indifference across the bottom, where the benefits (or disadvantages) of a good (or bad) asset location decision are often too small to make a material difference at all.

As the graph illustrates, in practice asset location decisions must be balanced between the anticipated tax efficiency of the investment and the expected returns. Accordingly, the chart indicates that in practice, bonds in today's low-yield environment should probably not be placed inside of IRAs - they fall in the zone of indifference! - and that the priority in the IRA instead should be given to higher return investments that are at least a little tax inefficient (even if they might be eligible for long-term capital gains or qualified dividends rates!). In fact, when working from the outside in - the most tax-inefficient high-return investments in the iRA, and the most tax-efficient high-return investments in the taxable account, the reality is that the bonds should actually just fall wherever they may... because, again, their returns are so low it actually doesn't matter very much compared to getting the other high-return asset locations right!

Fortunately, good decisions about asset location can be genuinely rewarding. The Daryanani and Cordaro paper estimates the executing a good asset location strategies averages about 20 basis points of "free" return, and the recent Blanchett and Kaplan article on "Gamma" suggests the benefit could be as large as about 52 basis points for retirees. In fact, the benefits of asset location are becoming so recognized that a new array of low-cost variable annuities are coming to the marketplace to serve as an asset location vehicle by allowing clients to "buy" tax deferral buckets for a reasonable price (buying the basic guarantees of an annuity they don't need just to get the tax-deferral feature they want), if they don't already have enough tax-preferenced investment accounts - which can be especially helpful to proactively provide a shelter to the most high-return-yet-tax-inefficient investments.

So what do you think? How do you prioritize your asset location decisions amongst various types of accounts and investments? Is asset location a priority in your portfolio design? Should it be?

Michael,

Great post! Yes, I make use of location in creating client plans and often, as you mention, there are trade offs when the client doesn’t have enough “room” in a tax deferred account to fit all the inefficient assets.

Probably the best source of info on this subject comes from Baylor’s Bill Reichenstein who wrote in depth about it here http://www.amazon.com/Presence-Taxes-Applications-After-tax-Valuations/dp/0979877512

He also advocates asset allocation on an after tax basis. Ex: if someone has $100k in their IRA do they really “own” all $100k if they are in a 25% tax bracket? Reichenstein points out that they have $75k in the IRA and this must be taken into account in creating “say” a 50/50 portfolio.

As a follow up..another question is which assets should go in a Roth. On the one hand I’d like to grow the Roth as large as possible by holding an asset that is expected to grow a rate greater than the market as a whole, say small cap value as an example. On the other hand since this is a riskier asset (greater chance of loss) I might want this in a taxable account so the gov’t can share in that possible loss.

Does anyone have an opinion on this??

Excellent work, Michael. Thank you.

Two other issues: 1) High growth assets (stocks) in the IRA are going to force higher taxable distributions which the client may not need; and 2)stepped-up basis on death will be lost with stocks in the IRA.

Hi Mike, good explanation. Here is the Bogleheads approach, but not focusing on low bonds yield environment:

http://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Principles_of_Tax-Efficient_Fund_Placement

If taxable and sheltered accounts are similar in dollar value, and no bequests are involved, why not have the same asset allocation in each account? It’s simpler and retirees could do it themselves and save the adviser’s fee. BTW, this is also Rick Ferri’s idea.

Re: “why not have the same asset allocation in each account?”

This whole article is an answer to that very question.

This is a great discussion – about a topic that I’ve spent a lot of time on myself, both as a CPA/RIA and as CEO of Total Rebalance Expert. I’ve always been a proponent of the “tried & true” asset location priorities: inefficient assets (bonds) in the IRAs, efficient assets (equities) in taxable accounts, and high risk/high return assets in the Roth. I still believe this theory to be the best one.

My reasons (in no particular order):

– Allocation decisions should be based on long-term expected returns not predicted current returns. These are long-term decisions and it is not efficient to move holdings back & forth when selling from taxable accounts can cause taxable gains (and selling from anything causes transaction fees).

– Having said that, from an investment standpoint, the advisor must always consider muni returns vs. taxable bond returns. If munis are better than after-tax bond rates, it might make sense to hold munis in the taxable account.

– Tax inefficiency typically means higher distributions of ordinary income with less appreciation. To the extent possible, these assets should be held in the IRA. This produces the benefit of lower RMDs and less “income in respect of a decedent.” Also, the point that building a higher balance in the IRA means a higher value in the portfolio doesn’t consider that we’re looking at the total portfolio and not just the IRA – which will eventually get taxed at ordinary rates no matter waht!

– Gains recognized in taxable accounts from rebalancing can often be offset by tax loss harvesting. Ultimately, these gains will be subject to lower capital gains rates or zero tax upon death. Holding these assets in IRAs converts zero tax or, at most, capital gains tax to ordinary tax that never goes away.

– Because Roth IRAs never get taxed, they are typically the last “pot” liquidated by the investor. Initial downturns can be reversed through recharacterization. Once past this phase, the Roth can handle volatility (due to its long-term nature) and the ultimate large growth will avoid taxation – even to the next generation!

Bottom line: I believe in the solid (conventional) rules for asset location!

Great points Sheryl!

Michael,

Great article – two thoughts:

1. I imagine that when I share this with our investment team they will say the biggest difficulty in implementing such a precise approach is that you cannot be certain which asset class will appreciate the most for over a given time period (this may be easier using your 30-yr time horizons, though). But, given that, I’m wondering…

2. How this concept integrates with mean reversion. Given that we know bonds are likely entering a low-growth period, it makes sense to move other asset classes to preferred tax buckets. However, could you create a strategy to reassess this continually, as other asset classes run their cycle? We turnover as much as 25% in our portfolio each year, so it would not be impossible to completely shift asset classes every 5-10 years.

Thanks,

Brian

I was surprised I didn’t see Morningstars Tax Cost Ratio mentioned – it’s a nice way to see how efficient a fund has been over 3,5, 10, and 15 years.

Also, not mentioned were potential “gains” from loss harvesting. Expected returns are important, but the range and volatility of return must be considered.

This is why I respectfully disagree with the conventional wisdom of putting high growth (and high volatility) investments in a Roth as Sheryl mentioned. If I had most of my Roth invested in emerging markets stock, I just gave up nice loss harvesting opportunities in 2008 and 2011 that I would have had if a brokerage account was used.

Chris,

We actually find most affluent clients who harvested excessively in 2008 now regret it. Their investments have bounced back, their gains are high (because they stepped their basis down when they harvested), and now the higher income is driving them up into the new top capital gains tax brackets. Harvesting gains actually resulted in NEGATIVE tax arbitrage for them.

Granted, there are certainly some scenarios where the harvesting turns out to work, but as I’ve shown in other articles here (http://www.kitces.com/blog/archives/455-Whats-The-Real-Value-Of-Deferring-Capital-Gains-Less-Than-Most-People-Think.html) the value is small.

More generally, if you find it valuable to defer a small amount gains by harvesting losses to offset, why wouldn’t it be even more appealing to defer the bulk of the gains from sheltering them? The value of tax-deferring the entirety of the growth is far greater than the value of tax-deferring a piece of the growth by creating a loss that causes an equal and offsetting gain in the future anyway.

In terms of Tax Cost Ratio, indeed not mentioned here, but I’d agree that’s certainly one useful method for trying to evaluate the tax efficiency of an actively managed mutual fund in particular. It’s definitely one of the factors we look at in building a tax hierarchy of investments and their tax efficiency.

– Michael