Executive Summary

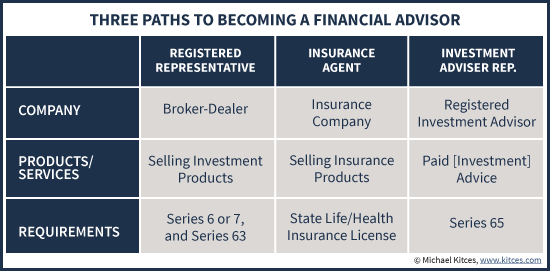

Virtually all financial advisors today follow one of three paths in becoming a financial advisor – either as a registered representative of a broker-dealer, an insurance agent with an insurance company, or an investment adviser representative of an RIA. And each path has its own licensing and exam requirements.

Yet the sad commonality of all paths to becoming a financial advisor is that the actual exam and educational requirements to be an advisor are remarkably low. In fact, the licensing exams for financial advisors do little more than test basic product knowledge and awareness of the applicable state and Federal laws, and none require any substantive education in financial planning itself before holding out to the public as a comprehensive financial advisor who will guide consumers about how to manage their life savings!

Given the roots of financial advising in the world of insurance and investment product sales, this isn’t entirely surprising. The licensing requirements to become a financial advisor, along with the suitability standard to which most advisors are subject, are built around the concept that “advisors” are really just product salespeople. And the bar to determine if someone is "capable" of selling a product isn't very high.

Ultimately, though, if financial advisors hope to actually be recognized as bona fide professionals, the requirements to become a financial advisor must become harder, and require actual education and experience to demonstrate competency as a financial advisor (not just compliance with the laws that apply to salespeople!). Otherwise, the reality is that even if a uniform fiduciary standard is implemented that requires all brokers and investment advisers to act in the best interests of their clients, consumers may still be harmed by advisor ignorance and the sheer lack of competency that would result from raising the fiduciary duty of loyalty but ignoring the equally important fiduciary duty of care – to only give advice in areas in which the professional is actually educated and trained to give advice in the first place!

Financial Advisor License Requirements - How To Become A "Financial Advisor"

Notwithstanding the popularity of the “financial advisor” job – now up to #25 on the list of “100 Best Jobs” from US News, with a projected jobs growth rate of 27% through 2022 from the Department of Labor – the reality is that the term “financial advisor” itself is largely unregulated. The requirements to become a financial advisor are not dictated by whether the person holds out to the public as a financial advisor, and there is no such thing as a standalone "financial advisor license". Instead, licensing requirements for financial advisors are based on the products that the financial advisor provides and how the financial advisor will be compensated for his/her services.

Registered Representative With A Broker-Dealer

For instance, to become a financial advisor who will implement investment (“securities”) products for a commission, you must complete FINRA registration and take certain exams. Most commonly, this will be the 2-hour Series 6 (for selling ‘packaged’ investment products like mutual funds or variable annuities) or the more comprehensive 6-hour Series 7 (for selling everything a Series 6 covers, plus almost any other securities-related product including direct stocks, bonds, options, and more), along with a 75-minute Series 63 (in most states) to affirm the individual understands applicable state securities laws as well. The exams require a passing grade of 72% (or only 70% in the case of the Series 6).

The process is generally accomplished by engaging initially with a broker-dealer, which will sponsor the individual to take the Series exams, after which the person becomes formally registered with FINRA (the regulator) and subsequently becomes a “registered representative” of the broker-dealer (who will oversee their sales activity, in exchange for keeping a portion of the income [commissions] earned).

Insurance Agent With An Insurance Company

By contrast, becoming a financial advisor who will sell/implement insurance products, from life or disability insurance to health insurance or long-term care insurance, must obtain a state insurance license. The exact requirements for these exams vary by state, but generally require some pre-education to learn the basics of insurance products and state insurance regulations, followed by a 1-2 hour exam, again typically with a required passing grade around 70%.

Once completed, the advisor then becomes appointed with one or several insurance companies to be legally able to act as the insurance company’s agent and sell its insurance products to consumers.

Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) with a Registered Investment Adviser (RIA)

The third primary path to become a qualified financial advisor is to give financial advice and get paid for it directly, i.e. by getting paid an advice or investment management fee (rather than a commission tied to an investment or insurance product).

Technically, advisors who wish to get paid a fee for their general advice can do so without being registered or regulated at all in most states; however, if the advice pertains to specific investment advice for which the advisor is compensated, it’s necessary to become registered as an investment adviser in any state(s) where the advisor has client(s). Ultimately, being so registered requires creating a business entity (or formally registering as a sole proprietor business) that will be the “Registered Investment Adviser” (RIA) entity with the state, and the individual becomes an investment adviser representative (IAR) of that company. Alternatively, a financial advisor might choose to work for an existing RIA (either registered in the state, or registered nationally with the SEC [for larger RIA firms]), becoming an IAR of that existing firm instead.

Becoming an IAR of an RIA (whether a new or existing RIA) requires the prospective advisor to complete a 3-hour Series 65 exam, which covers the state laws pertaining to getting paid for investment advice, and similar to other FINRA Series exams has a 72% required grade to pass.

Notably, in many states, any advisor who has CFP certification is automatically presumed to be delivering specific investment advice for a fee, and thus must become an IAR of some RIA registered in that state; however, many/most of those states also waive the Series 65 exam for CFP certificants, which means the advisor must simply go through the paperwork registration process (and pay the state registration fee) with the state securities department (but won’t necessarily have to take any licensing exams).

Financial Advisor Competency Standards For Advice Versus Product Sales

A notable commonality of all the current regulatory paths towards becoming a licensed financial advisor is that in the end, the actual regulatory exams focus on the basic structure and mechanics of the products being used (e.g., the Series 6 covers how mutual funds work, the Series 7 covers how stocks/bonds/options work, the life & health insurance license covers how those insurance products work). And the regulatory exams are also meant to ensure that the advisor understands the basic laws that will apply to him/her as an advisor. Notably absent from the licensing requirements for becoming a financial advisor, though, is any kind of test to determine if the “advisor” actually knows anything about money, finances, or advice!

In other words, the sad reality is that meeting the legal registration/licensing requirements to become a financial advisor is simply about understanding the relevant laws and products, and never actually involves demonstrating any competency in financial advice itself. Educational programs in financial planning and advice, and certifications like the CFP marks (or post-CFP educational programs beyond that), are purely optional, and while they are viewed as a “best practice” for advisors to have, the only actual requirement is a fairly minimal licensing exam. Which means there's actually no such thing as a certified financial advisor (just a licensed financial advisor who has voluntarily completed the Certified Financial Planner designation), and you can technically become a financial advisor with no experience at all!

By contrast, even becoming a hairdresser requires in most states the completion of a 9-month educational program in hairstyling for either a cosmetology certificate or an associate’s degree… which is 9 months more in educational requirements than it takes to become a financial advisor and provide consumers guidance about their entire life savings!

Given that the roots of becoming a financial advisor are in the sale of insurance or investment products, these regulatory standards are not entirely surprising. Because the fundamental difference in even a trade like hairstyling versus selling insurance or investment products is that one is an actual service with standards to which a professional can be held accountable, while the other is “just” the job of a salesperson selling products (in a world where 'caveat emptor' reins supreme!).

Accordingly, the only legal requirements to become a financial advisor are to get registered for the sale of products (and understand the laws that apply to such products), and the only “standard” of accountability for those financial advisors with their clients is the “suitability” standard (a legal standard for salespeople that requires them not to push products that are completely unsuitable for the recipient), not an actual advice-based fiduciary standard that requires advice to be delivered in the best interests of the client.

Sadly, though, it’s also worth noting that the standard for investment advice as an RIA – which is an advice-centric fiduciary standard – is actually still remarkably low as well, at least in the context of minimum requirements today. While the courts (or an arbitration panel) may sanction an investment adviser representative for failing to meet the standard of a prudent expert when working with clients, there’s still no actual requirement for the advisor to demonstrate in advance that he/she is capable of meeting such a competency standard; instead, advisors are turned loose on the public, and consumers can only seek legal recourse after the fact to recover any damages that result from a bad advisor’s incompetence. And, even the prudent man standard is still built primarily around prudent investment strategies, not all of the other areas in which a comprehensive financial advisor might provide financial advice. In other words, there's no clear accountability standard for advice when it comes to bad cash flow, budgeting, retirement, insurance, or income tax or estate planning advice!

Raising Educational Requirements To Become A Financial Advisor, And The Fiduciary Duty Of Care

Ultimately, if financial advice hopes to emerge as a bona fide and recognized profession, the standards for becoming a financial advisor in the first place need to be raised. A consumer-centric financial advice profession cannot be managed to a product-sales-based standard, with educational requirements significantly below even trades like cosmetology.

Notably, the issue of lifting the standards of advice has already been an ongoing issue of recent regulatory debate, from the potential for a uniform fiduciary standard for brokers and investment advisers, to the ongoing revisions to the Department of Labor’s proposals to expand the fiduciary standard by requiring even salespeople to sign a “best interests contract” with clients or risk that their commission-based compensation will be treated as a prohibited transaction.

The caveat to the current fiduciary debate, however, is that it is primarily about the duty of loyalty, and the idea that a bona fide advice professional should be required to give advice that is in the best interests of the client. While that is certainly one aspect of fiduciary advice – and an important one – it is not the only one. The other key to fiduciary duty is that even if advice is delivered solely in the interests of consumers, if there is no process to ensure the people delivering the advice are competent in the first place, consumers will simply be harmed out of [advisor] ignorance rather than greed or malice.

In other words, enforcing a fiduciary duty of loyalty on advisors - a "best interests standard" - without lifting the standard for the corresponding fiduciary duty of care, simply means that consumers will be harmed by the [well-intentioned-but-uneducated] advisor’s sheer incompetency, rather than his/her inability to manage conflicts of interest. In fact, given that most advisors are good and honest people and try to act in their clients’ best interests – regardless of whether they’re subject to a fiduciary standard that legally requires it – it’s likely the case that even now, most of the consumer harms caused by salespeople posing as financial advisors are due to a lack of training and education, not a deliberate attempt to take advantage of clients. And while most financial advisors are required to acknowledge at least some limitations to their scope of care and competency – e.g., disclosures from advisors that their ‘advice’ does not constitute formal tax or legal advice – even within the broad realm of financial advice, advisors commonly give “advice” far beyond the scope of their actual education and training (especially given that no advice-related education is required at all!). Though in a fiduciary future, failing to limit the scope of advice that goes beyond an advisor's competency could expose them to legal liability.

Financial Planning As A Recognized Profession

The bottom line is that most bona fide professions (e.g., doctors, lawyers, etc.) have not only a fiduciary duty to act in the interests of their clients, they also have substantive competency requirements to become a professional in the first place, including both extensive (graduate-level) educational requirements and what is often an experience or outright ‘apprenticeship’ (e.g., residency) requirement as well.

By contrast, financial advisors still only must take a minimum regulatory exam about the laws that apply to selling products, with no experience requirement, and no educational requirements regarding financial advice itself. At best, our educational standards – like earning the CFP certification – are purely voluntary, and sadly even the CFP marks have been trending recently towards a lower experience requirement, not a higher one.

Which means in the long run, even the fiduciary battle now being waged about acting in the best interests of clients is victorious, it will really just be one step in the ongoing process of lifting the standards for financial advice. The duty of loyalty may be the battleground today, but the duty of care and a competency standard for financial advisors won't be far behind, as it is essential for truly protecting the public. After all, financial planning is sacred work to clients – as is the work of any bona fide profession – which means in the long run, the requirements for becoming a financial advisors should be reasonably stringent and challenging, in terms of both managing conflicts of interest for the client's benefit, and having the professional competency to give the advice, too!

So what do you think? Are the requirements to become a financial advisor too easy in today's environment? Should the educational and experience requirements be lifted, along with other proposed fiduciary reforms? Should financial advisors actually be tested for their financial knowledge before being allowed to receive financial licenses for giving financial advice to the public?