Executive Summary

In an environment where generating portfolio alpha is difficult, strategies like managing assets on a household basis to take advantage of asset location opportunities to generate “tax alpha” are becoming more and more popular. The caveat, however, is that making effective asset location decisions is not easy, either.

For instance, while the traditional asset location strategy “rule of thumb” is that tax-inefficient bonds go into an IRA, while equities eligible for preferential tax rates go into a brokerage account, the reality is that for investors with long time horizons the optimal solution may be the opposite. Once stock dividends and portfolio turnover are considered, the ongoing “tax drag” of the portfolio can be so damaging to long-term returns that placing equities into an IRA may be more efficient, even though they are ultimately taxed at higher rates!

In fact, it turns out that almost any level of portfolio turnover will eventually tilt equities towards being held in IRAs given a long enough time horizon (and especially while today’s low interest rates result in almost no benefit for bonds to gain tax-deferred growth inside of retirement accounts). Which means in the end, good asset location decisions depend not only on returns and tax efficiency, but an investor’s time horizon as well!

Asset Location Strategies For Stocks And Bonds Across Taxable And Retirement Accounts

The challenge of asset location is to determine, once the investor is committed to a multi-asset-class portfolio and has multiple types of accounts (e.g., taxable account vs IRA), into which accounts should each asset class be placed. In other words, do you put the stocks in the IRA and the bonds in the taxable account, or vice versa with the bonds in the IRA and the stocks in the taxable account?

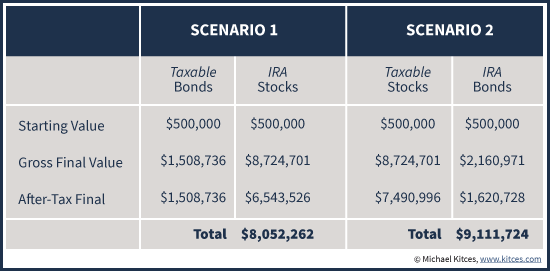

A simplified analysis would simply compare the after-tax growth rates between the two options over time. For instance, assume the investor has $500,000 in an IRA and $500,000 in a taxable (brokerage) account, and wishes to implement a 50/50 portfolio of stocks and bonds. The stocks are assumed to grow at a long-term return of 10%, and the bonds at 5%. The IRA is taxed (at 25% ordinary income rates) at the end upon liquidation, the stocks in the taxable account are also taxed at the end upon liquidation but at 15% long-term capital gains rates, and the bonds in the taxable account are simply taxed annually (also at 25% ordinary income rates).

Over a 30-year time horizon, the accounts would grow as follows, depending on (as noted earlier) whether the bonds are in the taxable account and the stocks are in the IRA (Scenario 1), or vice versa with the bonds in the IRA and the stocks taxable (Scenario 2).

As the results reveal, there is a significant benefit to holding bonds in the IRA and stocks in the taxable account, with a final wealth level that is almost $1.1M greater than the alternative asset location strategy.

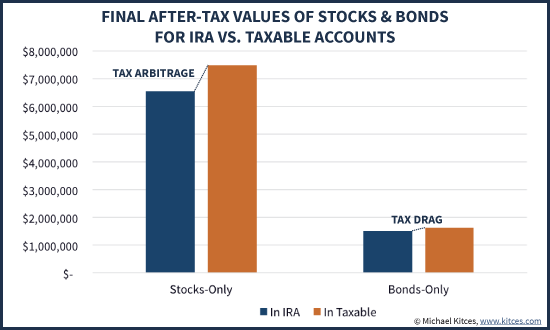

To a small extent, this is because the after-tax value of the bonds is greater when they can grow tax-deferred inside the IRA and be taxed once at the end, rather than face the ongoing "tax drag" of annual taxation (and ironically, this benefit would be diminished even further in today’s low interest rate environment!). However, the greater driver of the outcome is actually the difference in the final value of equities; whether held in the taxable account or the IRA, the compounded value is the same before taxes, but the fact that the IRA is taxed at ordinary income rates while the taxable account is subject to preferential long-term capital gains rates leads to a “tax rate arbitrage” benefit for stocks to be held in the lower-tax-rate account.

Impact Of Dividends And Turnover On Asset Location Strategies For Stocks

Notably, the above scenarios above favor placing equities in a brokerage account to take advantage of the available tax rate arbitrage in part because of the implicit assumption that there is no tax drag at any point along the way. In other words, it is assumed that none of the equity return is attributable to (annually taxable) dividends, and it is assumed that the portfolio’s turnover is a perfect 0%.

Of course, in the real world, virtually all equities pay at least some ongoing dividend (or at least, maintaining a zero-dividend-portfolio would be almost impossible in a well-diversified portfolio). Even the S&P 500 has a dividend close to 2% in today’s marketplace, and historically the median dividend rate for large-cap US stocks has been almost 4.4% over the past 100+ years. Yet this is significant, because the presence of ongoing dividends as a component of total return can have a material adverse impact on the value of holding equites in a taxable account!

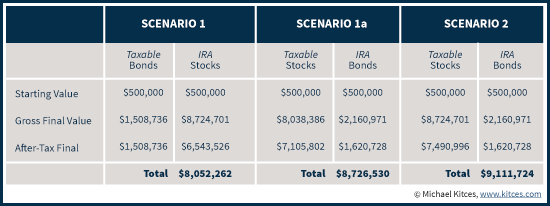

For instance, the chart below shows the outcome of placing stocks in a taxable account and bonds in an IRA, assuming the long-term 10% total return on equities is comprised of a 2% dividend and 8% appreciation. In this case, the dividends are still assumed to be qualified, and eligible for favorable (long-term capital gains) tax rates.

As the results reveal, the presence of even just a small dividend has a material impact. By just assuming 2% of the 10% equity return is a (favorably taxed) dividend, with the after-tax proceeds of the dividend reinvested annually, the benefit of holding stocks in the taxable account is chopped by almost 40%! Thanks to the ongoing tax drag of the dividend, holding stocks in the taxable account finishes “just” about $700,000 above the value of holding stocks in the IRA, instead of nearly $1.1M higher.

However, once we account for the impact of turnover, the situation gets far worse. In the extreme, imagine that all growth is taxable annually (albeit still eligible for preferential capital gains rates), which means in essence that the equities in a taxable account simply grow at 8.5% instead of compounding at 10% and being taxed (at 15%) at the end.

This “worst possible” turnover scenario has a dramatic effect, chopping the final value of the equity portfolio down to only $5.78M, and the combined value of the stock and bond accounts to only $7.4M. In other words, while there is a tax rate arbitrage to hold equities in a taxable account, the stocks actually grow so inefficiently due to tax drag that in the long run, it’s actually better to hold them inside the IRA and pay the higher ordinary income rates upon liquidation in order to get the benefit of tax-deferred growth along the way!

Asset Location Strategy For Equities In Light Of Portfolio Turnover Rates

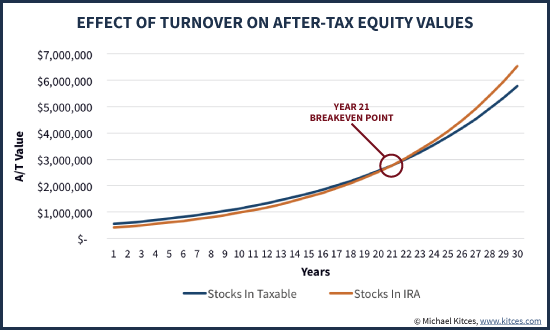

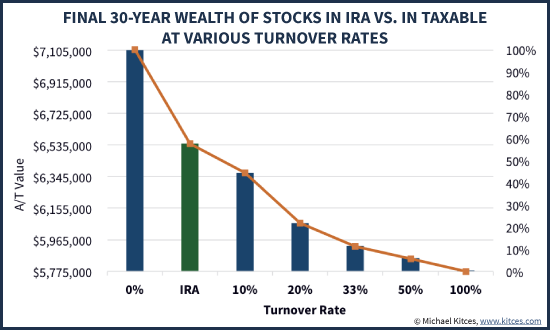

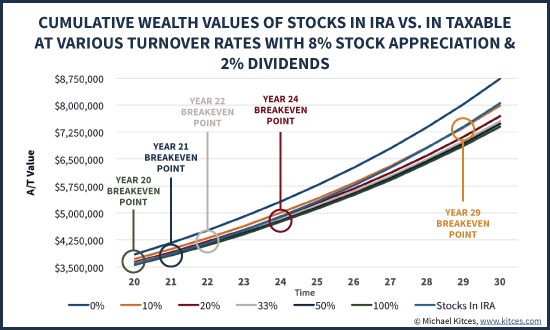

Of course, most investors aren’t going to have 0% turnover for life, nor 100% annual turnover, but something in between. Accordingly, we can examine the impact of varying levels of turnover, from 10% (portfolio changes once per decade), to 20% (changes every 5 years), to 33% (turnover every 3 years), 50%, out to the extreme of 100% (annual) turnover. These results, relative to “just” holding equities in the IRA and putting bonds in the taxable account instead, are shown below.

As the results reveal, virtually any level of turnover in stocks ultimately leads to the compounded value of equities in the brokerage account to be lower than just holding equities in an IRA and paying the taxes at the end upon liquidation (e.g., when the money is spent). The higher the rate of turnover, the greater the benefit to holding equities in the IRA, and the faster the “crossover” point that the benefit of tax-deferral outweighs the tax-rate differential, as shown below.

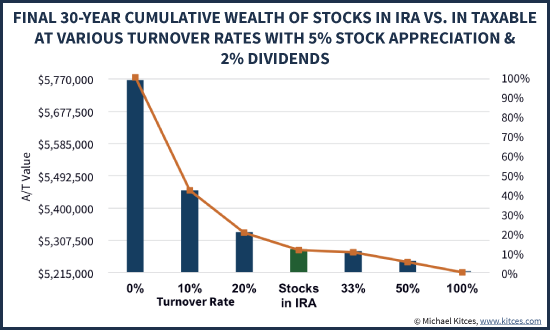

Notably, the benefits of obtaining tax-deferred compounding growth for equities inside of an IRA are impacted not only by the tax-efficiency of the stocks, but also are driven heavily by the overall expected return on stocks in the first place. At lower returns, there is somewhat less value to seeking out tax-deferred growth. For instance, if the long-term appreciation for equities is only 5% (which on top of a 2% dividend would lead to a total return of “just” 7%), there is still a benefit to holding equities inside an IRA in the long run, but not as much:

In addition to the fact that lower equity returns make them somewhat less favorable to hold within an IRA (or at least, it will require a longer time horizon for the compounding benefit to bear out), higher volatility also makes them somewhat less favorable to hold inside of an IRA, as volatile equities held in a brokerage account may have more opportunities for tax-loss harvesting. On the other hand, given the limited benefits of tax-loss harvesting, and the growing embedded tax liability that emerges from implementing it systematically over time (which in turn can drive up the investor’s capital gains rates as high as 23.8%), for very-long-term investors the compounding benefits in the IRA may still outweigh. It’s also notable that foreign equities are less valuable to hold inside of an IRA than US stocks, due to the loss of the foreign tax credit for any taxes paid overseas. Fortunately, though, the damage is diminished by the fact that taxes are typically withheld at the source and never paid out in the US means they are effectively deductible even if the credit is lost, and many countries have tax treaties with the US that limited foreign tax withholding in the first place.

On the other hand, to the extent that a portfolio’s turnover triggers not just long-term capital gains but also some short-term gains, and/or if any of the dividends paid out from the equities are non-qualified (and therefore taxed at ordinary income), it will be even more favorable to hold the equities inside of an IRA. Mutual funds with embedded gains that may potentially be distributed in the future will also benefit more by being held inside of an IRA. And of course, for investors facing higher tax rates, the anti-compounding effects of portfolio tax drag are even more severe, and favor tax-deferred compounding growth inside of an IRA even more.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: the idea that the preferred asset location of equities is “always” a brokerage account to take advantage of favorable long-term capital gains rates, while tax-inefficient bonds would be placed in an IRA, is not always correct. In reality, the outcomes are sensitive not only to the expected returns and the tax-efficiency of the investments, but also to the time period for investing. And over multi-decade time horizons (and with IRAs that can be stretched, the time horizon could be multi-generational!) the benefits of tax-deferred compounding growth can outweigh the tax rate differential. In fact, with almost any level of turnover, the ideal asset location strategies change entirely, with stocks perform better in the long run in an IRA... and especially when there is a substantial dividend and/or any level of turnover (which could be triggered by rebalancing alone!).

Michael, as usual, a well-written peace.

My findings in this area are similar to yours. For a simple “buy and hold” portfolio of a few stocks, taxable accounts are usually a way to go.

However, once you incorporate a very long-term investment horizon, dividends and income reinvesting, rebalancing, and more importantly regular contributions to an account, tax-deferred accounts turn out to be unbeatable.

what could/should be the allocation though to accommodate tax-efficient rebalancing? Some stocks in the IRA could be sold tax-free to rebalance after outperformance, and some Muni bonds could be held in the taxable account to be sold when bonds outperform. Any idea or research on an optimal stock/bond blend in the taxable/IRA accounts to not only address after-tax return efficiency but also in the face of rebalancing (and as alluded tax loss harvesting)?

This is a fine blog, I am just dropping by in support. Also I would hope you can take some time to peruse my website and give us some feed back on your thoughts pertaining to retirement investing and long term residual income. Thanks! I believe real estate is a great way to insure financial success after retirement.

Passive Residual Income and Assets – earn 10-12% principal-protected returns in our Private Lenders Network – http://www.priaa.com – 214 919 4615

Passive Residual Income and Assets http://www.priaa.com – a lending network for short-term capital (bridge loans) Call 214 919 4615 http://www.priaa.com

I would be curious to see how the numbers change when you use an equal asset allocation in both accounts. However, in the taxable accounts you would use muni bonds for fixed income. Any insight into how those numbers would look?

This suggests (and experience bears this out) that as one approaches 70.5 and the RMD requirement, an investor who has been equity heavy inside the IRA (and bond heavy outside) might want to consider moving in the other direction. Which means there should be ongoing planning for the transition during one’s 50’s and 60’s.

If you put your stock portion into a fund like Vanguard Total Market (VTSMX) which has a turnover rate of 3%, would Stocks in Taxable then beat Stock in IRA (for the 10% appreciation chart)?

I’m trying to understand this conceptually. I think what is happening is that the higher (than bonds) compounding interest on the untaxed dividends is what really makes the equities-in-IRA win in the long term. So it’s really the higher growth rate of the equities that is causing the eventual crossover.

Also, is the legend of your first bar graph flipped?

RMDs are the reason you don’t want to end up with $8M in a Tr. IRA, and why stocks-in-taxable holds in almost all circumstances.