Executive Summary

Financial advisors are generally required to abide by ethical standards, such as the duty to act in a client’s best interests when giving financial advice. Advisors who attain the CFP marks are held to even higher standards, though, with all CFP certificants required to adopt CFP Board’s own more-stringent Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct. It would stand to reason, then, that advisors who are CFP certificants would be less likely to engage in professional misconduct than their non-CFP counterparts, since they voluntarily adopt this higher standard of ethical conduct in order to use the CFP mark.

A forthcoming study by Jeff Camarda et al. in Journal of Financial Regulation, however, concludes the opposite. The paper’s authors state that based on their review of publicly available data, CFP certificants had higher levels of advisor-related misconduct than non-CFPs. Which, if true, would be a surprising and concerning revelation, particularly for CFP certificant advisors (as well as for CFP Board itself) who view the CFP marks as the ‘gold standard’ of financial planning – in large part because of the higher standards of conduct required – because of the risk to their reputation should those marks instead be associated with a higher likelihood of misconduct.

But a closer look at the data used in the study reveals issues with the authors’ conclusions. The paper examines advisory-related misconduct data for more than 625,000 FINRA-registered individuals (specifically those who have filed Form U4) and compares the rates of misconduct between CFP and non-CFP certificants. The issue, however, is that not everyone who files Form U4 is an advisor – many assistants, executives, researchers, traders, and other types of professionals are also required to register with FINRA. In fact, according to industry research, there were only about 292,000 financial advisors in total as of 2020, meaning it’s possible that less than half of the individuals used in the study were actually financial advisors. Meanwhile, the vast majority of CFP certificants are financial advisors – meaning it's hardly surprising that CFP certificants were found to be more likely to have histories of advisory-related misconduct than other U4 filers, simply because they were much more likely to be financial advisors in the first place!

Previous research by Derek Tharp et al. attempted to identify actual financial advisors and control for other non-certification-related factors, and found (among a smaller sample size) that CFP certificants were actually less likely to have engaged in advisory-related misconduct than non-CFP professionals. Which highlights a key issue in misconduct-related research, which is that researchers’ conclusions are only as trustworthy as the data that goes into the study. Because when similar research attempts to explore rates of misconduct using other variables – such as firm size, fee models, client types, etc. – without being careful to search for unrelated factors in the data that could inadvertently skew the outcome, it can result in similarly ‘surprising’ conclusions that are really just a reflection of spurious relationships based on poor data quality rather than reality.

The key point is that even – or especially – when looking at research based on big data, it’s still important to rely on logic when interpreting the results. Sound research may certainly produce conclusions that go against intuition, but when such surprising results do occur – such as finding that CFP certificants commit misconduct at higher rates despite voluntarily adopting a higher standard of conduct than non-CFPs – it’s often the case (after a closer look at the data) that the more logical conclusion is the correct one.

Do CFP professionals engage in more misconduct than non-CFP professionals? That’s a striking suggestion and something that goes beyond claims from prior academic work that has received attention in the media that CFP professionals simply don’t seem to differ from non-CFP professionals in terms of misconduct. It rightfully raises some eyebrows to hear that CFP certificants – those who voluntarily submit to a Code of Ethics more stringent than legally required – are out in the marketplace engaging in more misconduct than other advisors.

Fortunately for CFP professionals, however, it’s not true.

On February 18, authors Jeffrey Camarda, Steven Lee, Pieter de Jong, and Jerusha Lee published an article titled “Badges of Misconduct: Consumer Rules to Avoid Abusive Advisors” in Journal of Financial Regulation.

The abstract of their paper states the following [emphasis added]:

…Using an advisor misconduct scoring framework we report specific misconduct ratings for each of the 625,980 Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) advisers, finding elevated misconduct for Certified Financial Planner (CFP®) professionals and commission/fiduciary licensees…

Pretty concerning finding if you take it at face value, but let’s dive deeper and see what is actually happening.

Author’s Disclosure: Before we dive into this research, I do want to state that I know the authors have worked hard on this project. I’ve previously published with several of the authors, and, at one point in time, I was involved with and contributed financially to this particular project. I voluntarily left the project after some disagreements with another contributor to the project, who ultimately seemed to have stepped away from the project, as well.

What’s Wrong With Most Research on CFP Professional Misconduct

Studies like the current Camarda et al. paper forthcoming in Journal of Financial Regulation have largely relied on regulatory data to evaluate advisor misconduct. Because certain information is reported and publicly available on all securities-licensed individuals, various companies and researchers have seized the opportunity to build data sets off of this regulatory data and explore questions such as, “Do CFP professionals engage in misconduct at higher rates than non-CFP professionals?”

It's a very reasonable question to ask, and it’s a question that has important industry and regulatory implications. It’s no surprise that researchers have been drawn to these types of questions, but this is a case where we have to be very careful about understanding the limitations of the data sets we are working from.

Form U4 is one of the most important regulatory documents for building these data sets. The FINRA website states, “Representatives of broker-dealers, investment advisers or issuers of securities must be registered with the appropriate jurisdictions and/or self-regulatory organizations (SROs). The Form U4 (Uniform Application for Securities Industry Registration or Transfer) is used to establish that registration.”

Perhaps the most crucial thing to be aware of in understanding the limitations of these data sets is that many non-advisors are also required to file U4s!

This point bears repeating: Many people who file U4s are not financial advisors. They may be assistants, executives, researchers, traders, compliance folks, and all sorts of others who are required to maintain securities licenses as a part of their job.

Thus why, in addition to the Series 6, 7, 63, and 65 exams that financial advisors are familiar with, there’s also a litany of other Series exams available from FINRA, including the Series 57 (Securities Traders), Series 79 (Investment Banker), Series 82 (Private Securities Offerings), Series 86/87 (Investment Research Analyst), Series 99 (Operations Professional), in addition to the Series 30–34 licenses (for Futures trading), Series 50–54 licenses (for Municipal Securities), not to mention a wide range of Principal-level Series licenses for everything from Options Principals (Series 4) to Investment Company Products Principal (Series 26) to Direct Participation Program Principals (Series 39) to General Securities Principals (Series 24).

Recall the 625,980 FINRA-registered individuals mentioned in the abstract of the forthcoming article by Camarda et al. Are there 626,000 advisors? No, because a significant number of them are registered in these various other non-advisor-related roles in the securities industry. In fact, Cerulli Associates estimates that there were roughly 292,000 advisors across all channels in 2020. This is another point that bears repeating. Cerulli Associates estimates that the total advisor headcount is less than half of the “advisors” included in the Camarda et al. data set, because FINRA requires registration of a wide range of industry roles that have nothing to do with being a financial advisor.

Now, this wouldn’t be an issue if we actually had a way of identifying advisors in the data sets, but unless we enrich these regulatory data sets beyond what can generally be scraped from the limited publicly available data on FINRA-registered individuals (more on that later), we don’t have any way of identifying who in the data set is actually an advisor. Essentially all of these individuals are treated as advisors, even though we know that more than half of them are not. That’s a big issue!

Recall again that the study in question is interested in advisory-related misconduct. Which group of individuals do you think would be more likely to have engaged in advisory-related misconduct: (a) financial advisors, or (b) non-financial advisors who also happen to be registered with FINRA for other non-advisory jobs?

I hope the answer to that question is obvious, but, to be clear, financial advisors are far more likely to have engaged in advisory-related misconduct. This is like asking whether financial advisors or physicians are more likely to have engaged in medical malpractice. Clearly, physicians are more likely to engage in medical malpractice because, well, they’re the ones practicing medicine.

But what about the claimed relationship between misconduct and CFP certification status – how does that play into all of this?

Well, let’s ask a similar question to the one posed before: Which group of individuals do you think would be more likely to hold the CFP mark: (a) Financial Advisors, or (b) Non-Financial Advisors?

Again, I hope the answer is obvious here, but financial advisors are more likely to be CFP certificants than non-financial advisors.

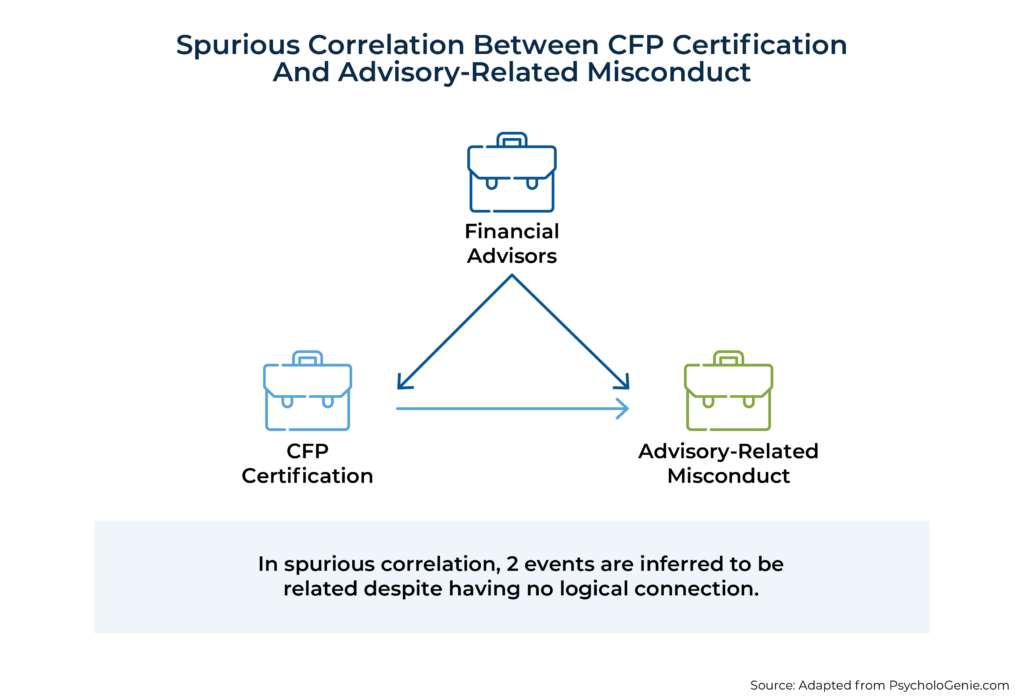

This is a classic spurious correlation. A relationship is observed between CFP certification and advisory-related misconduct, but the 2 are not actually related to one another; rather, it’s simply the fact that being a financial advisor is correlated with both (a) being a CFP professional, and (b) having engaged in advisory-related misconduct, which is especially highlighted when they’re compared to a group where the majority are not financial advisors at all.

Now, a reasonable skeptic might say, “Derek, this is all well and good, but do you actually have any data to back this up?” And yes, reasonable skeptic, we do! In fact, it comes from another paper co-authored by me and 3 of the most recent Camarda et al. co-authors.

Evidence Of The Spurious Relationship Between CFP Certification Status And Advisory-Related Misconduct

As mentioned above, one of the biggest challenges with really diving deep into research on advisory-related misconduct is the fact that there’s no question on the U4 that asks, “Are you truly a client-facing financial advisor?” The U4 is used for all sorts of securities-licensed individuals. Fortunately, however, there are some data vendors that enrich regulatory data, such as Discovery Data, that use various methods to try and identify who is or is not an actual client-facing advisor.

While there is inevitably going to be an error in any sort of attempt to classify advisors and non-advisors within the total universe of securities-licensed individuals, it’s worth noting that data vendors providing these types of services have some significant skin in the game. If wholesalers or others within the industry are purchasing their data to reach financial advisors that they want to market/wholesale to, they’re going to want to have reliable data. Data-vendor clients are not going to be happy if individuals are listed as client-facing advisors, but a wholesaler gets them on the phone and finds out they are not.

So I make no claims here that data vendors are perfect in their classification, but they have some very strong market-based incentives to try and get it right. And their ongoing commercial success suggests that those who purchase the data for business purposes are finding that the data is at least reasonably accurate.

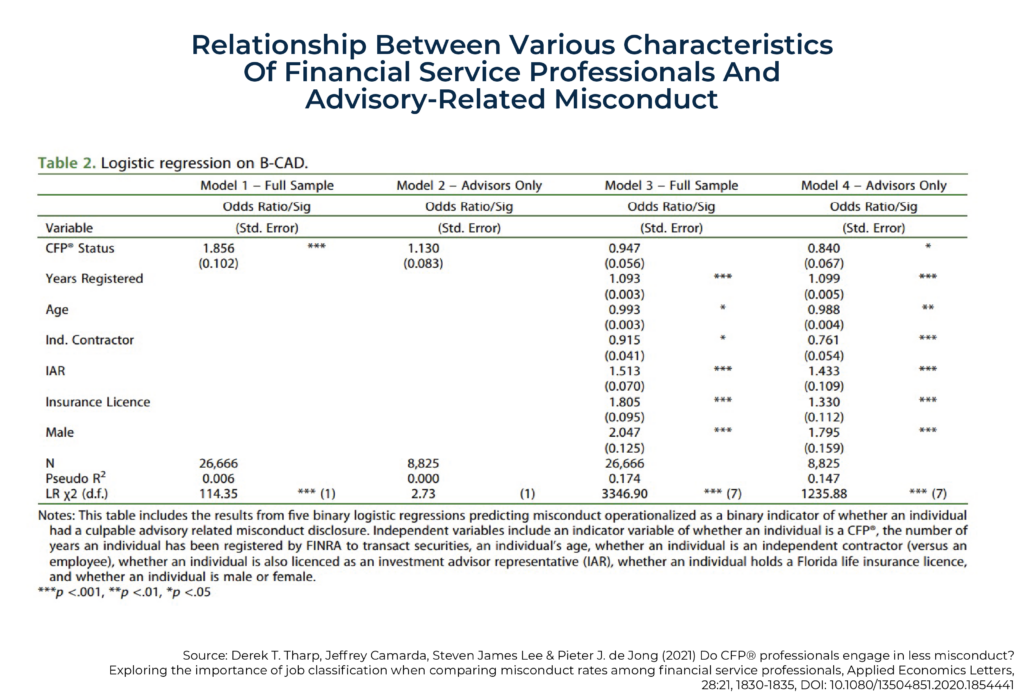

Fortunately, data vendors are also willing to sell their data to researchers for use in academic research. In a 2020 study titled “Do CFP® professionals engage in less misconduct? Exploring the importance of job classification when comparing misconduct rates among financial service professionals” published in Applied Economics Letters by me, Jeffrey Camarda, Steven James, and Pieter de Jong, we used some enriched regulatory data to examine whether the inclusion/exclusion of enriched data impacted the results of CFP professional misconduct research.

What we found was precisely consistent with the spurious relationship I outlined above.

First, we used all FINRA-registered individuals within the data set, and we looked to see whether CFP certification status alone would be associated with advisory-related misconduct. Here’s an important snippet from the abstract of that study:

…When using CFP® status as the sole predictor of misconduct among the full sample of licensed individuals, CFP® professionals are found to have 1.86 times higher odds of having engaged in culpable advisory-related misconduct compared to non-CFP® professionals.

So, in other words, within the data set we were using, we observed the same relationship touted in Camarda et al.’s latest forthcoming paper in Journal of Financial Regulation, that CFP certification was positively associated with advisory-related misconduct.

Notably, the data set we were using was not as large as the one used by Camarda et al. Our data set was limited to only individuals in Florida (due to cost limitations in buying access to a broader data set), but we were still dealing with a large sample of individuals. The full sample was 26,666 individuals.

However, there were only 8,825 individuals who had been identified by the data vendor as solely operating financial advisors. And so, our next step was to carry out the same analysis (using CFP certification status as the sole predictor of advisory-related misconduct), but to do so only among the 8,825 individuals actually identified as financial advisors. In this case, contrary to the often-cited positive relationship between CFP certification status and misconduct, we found no statistically significant relationship between CFP certification and misconduct.

We also repeated a similar process to the analysis described above, but instead also included a number of other factors previously found to be associated with advisory-related misconduct, such as age, years registered, IAR status, insurance license status, independent contractor status, and gender (although, admittedly, some of these control variables may be spurious relationships themselves). In this updated analysis among only those identified as financial advisors, there already was no relationship between CFP certification and advisory-related misconduct among the full sample when other factors were controlled for, but once the sample was limited to only the 8,825 individuals identified as financial advisors, the relationship actually flipped to a negative relationship between CFP certification status and misconduct. Here’s another relevant snippet from our abstract:

However, after controlling for other relevant factors and limiting the sample to only individuals identified as financial advisors, CFP® professionals are found to have 0.84 times lower odds of having engaged in culpable advisory-related misconduct. Because job classifications are generally not available in the standard SEC and FINRA data sets, these findings illustrate how the inability to control for unobserved differences in job roles may bias misconduct analyses.

In other words, once we controlled for factors previously found to be relevant and limited the study to only individuals identified as working solely as client-facing advisors, the relationship flipped from CFP professionals being more likely to engage in culpable advisory-related misconduct among the full sample with a limited model, to less likely to engage in misconduct when limited to only advisors and controlling for other relevant factors.

Here's a look at our full results for those who may be interested:

But the key point here is that we found exactly what one would expect to find if there was a spurious relationship between CFP certification and misconduct.

What To Do Going Forward

While we’ve focused solely on misconduct-related studies here, the reality is that this issue plagues a lot of research that has been conducted using similar regulatory data.

Back in 2016, Michael Kitces noted that this very issue was present in the famous study, “The Market For Financial Adviser Misconduct”, published in Journal of Political Economy and conducted by Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos, and Amit Seru. In this study, the authors also included all sorts of non-advisors in their “over 650,000 registered financial advisers” included within their sample… which, in reality, were simply 650,000 FINRA-registered individuals, a portion of whom also happened to be financial advisors.

Kitces was absolutely right to point this issue out. Unfortunately, however, I’ve paid close attention to the research using these data sets, and, to date, other than myself, Kitces is the only person I’ve encountered who has ever raised this issue. I’ve tried to bring attention to the issue in conferences and other various academic forums, but my concerns generally get waived away as some pedantic nuisance that doesn’t really matter. “Look at our big data! Isn’t it sexy?” But the truth is, it does matter!

Kitces noted back in 2016 that the inclusion of non-advisors could water down the results and understate problems associated with misconduct – since including people unlikely to engage in misconduct is going to understate the prevalence of misconduct. And while that is true on an absolute basis, it’s also worth noting that, on a relative basis, this can have the opposite effect of creating the illusion of greater disparities in misconduct level than there truly are.

As we saw within the Tharp et al. study examining CFP professional misconduct above, including people who are extremely unlikely to engage in any sort of misconduct in a misconduct study can create spurious correlations that create the illusion of ‘problems’ where they don’t actually exist.

Consider just one particularly illustrative example within the Egan et al. “Market for Misconduct” paper. The authors conclude that some firms ‘specialize’ in misconduct. Those would be some of the firms with the highest levels of misconduct.

One such firm identified was Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network, LLC, which had a misconduct rate of 15.3%. By contrast, Wells Fargo Securities, LLC was one of the firms with the lowest misconduct rates at only 1.7%. Similarly, the paper reports nearly identical contrasting results, such as UBS Securities being a low misconduct firm and UBS Financial Services being a high misconduct firm.

But let’s take a step back and think about this. Should we be even the least bit surprised that Wells Fargo Advisors has a much higher rate of misconduct than Wells Fargo Securities?

Of course not. We should expect Wells Fargo Advisors to have a much higher misconduct rate than Wells Fargo Securities because securities-licensed individuals at Wells Fargo Advisors are far more likely to actually be client-facing advisors. People at Wells Fargo Securities, who are primarily focused on institutional (not retail) investing, are more likely to be traders, investment research analysts, or someone else who has to have a FINRA license for their internal role but who would be extremely unlikely to generate a typical complaint that would result in a client-facing advisor-misconduct report (because they literally don’t sit across from and meet with individual clients).

If we’re looking at the Wells Fargo entities above, our conclusion shouldn’t be that the culture at Wells Fargo Advisors is toxic or that the culture at Wells Fargo Securities is pristine. Maybe the culture at one or both firms is either toxic or pristine, but we don’t know when we’re making an apples-to-oranges comparison of advisor misconduct between a firm that employs client-facing advisors and a second firm that does not (where the former would naturally be expected to have higher levels of advisor misconduct a priori because that’s where the advisors are).

Now, I should note that there is some mention of the use of data vendors precisely for some robustness testing to enrich some of the Egan et al. data – so I do want to give credit to the authors for that –but the primary analyses reported in the paper do not make use of sufficiently enriched data to truly get at what’s driving misconduct. Here’s a sampling of some of their takeaways:

- IARs are 50% more likely to commit financial advisor misconduct. Surprising? Of course not. IARs are far more likely to work in client-facing advisor positions where they could commit such misconduct in the first place.

- Firms that advise retail clients are more likely to engage in new misconduct. Surprising? Of course not, because advisor misconduct is almost by definition retail-client-facing.

- Firms that advise retail clients are more likely to employ an advisor who was previously disciplined for misconduct. Surprising? Of course not, as where else would an advisor (including one with prior misconduct) work?

- Firms which charge hourly or based on AUM are more likely to engage in advisor misconduct. Surprising? Of course not, because individuals who charge such fees are more likely to actually be financial advisors (and not some other FINRA-registered non-advisory role) in the first place.

- Firms which charge performance fees are less likely to engage in advisor misconduct. Surprising? Of course not, because the SEC actually bans most client-facing financial advisors from charging performance fees to begin with.

I can go on and on, but so much of the study is built on analyses that are fundamentally comparing apples (financial advisors) and oranges (all FINRA-registered individuals, nearly half of whom aren’t financial advisors in the first place).

And my point here is not to pick on Egan et al. – they are all far more talented researchers than I am and could also run circles around me. The lengths they went through to build their data set are tremendously impressive. The quantitative work is phenomenal. And they got a study published in Journal of Political Economy, one of the most difficult journals to publish in the world. There’s a lot to be impressed with in their study. But, fundamentally, we still have a garbage-in-garbage-out problem that plagues almost all of the research in this field; the quality of analysis on financial advisors simply isn’t relevant if it starts from a flawed data set where the majority of those included aren’t actually financial advisors.

To criticize myself (in the Tharp et al. study mentioned), there are so many relevant factors that we didn’t get the opportunity to look at in our work. One particular concern with these lines of misconduct research is that we could start to demonize firms or advisors that simply deal with markets, niches, or business models, where we should expect to have higher rates of reported and/or actual misconduct.

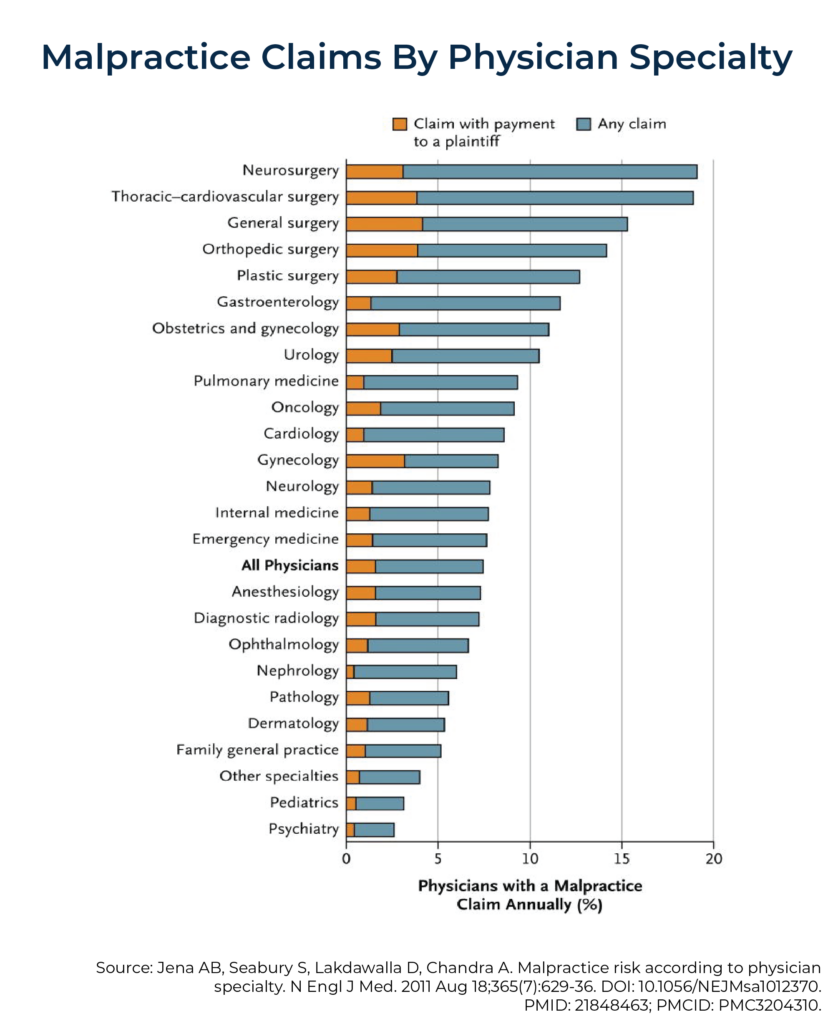

Consider the image below that looks at malpractice rates by medical specialty:

Should we conclude from the chart above that neurosurgery is particularly problematic while psychiatry is not? If we were only looking at firms and we knew nothing about firm specialties, should we conclude that firms engaging in neurosurgery are ‘specializing’ in misconduct? After all, such firms (neurosurgery) are more likely to face new malpractice claims and also likely to employ individuals (neurosurgeons) with previous malpractice claims.

Of course, this is all silly, and we know that there are different risk profiles associated with working in neurosurgery versus working in psychiatry. There’s a greater risk that things can go wrong in neurosurgery, and the harms when things do go wrong are greater, both of which increase the likelihood that a patient files a malpractice claim. It’s just a different risk profile entirely.

Granted, that’s not to say that you couldn’t have some firms that are really bad apples with a culture of taking excessive risks or otherwise putting clients in harm’s way. But to really drill down and figure out precisely what’s going on in a particular medical specialty, we could never just rely on a data set of all medically licensed professionals that mixes in client-facing professionals, administrative staff, legal folks, and all sorts of other people.

To bring this back to the financial advisory context, there are many ways we could accidentally demonize people who just happen to work within a particular niche or serve a particular market. Who among the following do you think would be more likely to have reported misconduct?

- An advisor who services 250 clients, or an advisor who services 25 clients

- An advisor who has been in business for 20 years, or an advisor who has been in business for 2 years

- An hourly advisor who has worked with 1,500 clients over the past 10 years, or an AUM advisor who has worked with 150 clients over the past 10 years

- An advisor who spends 90% of their time in an executive role, or an advisor who spends 100% of their time in client-facing work

- An advisor who works with 100 attorneys, or an advisor who works with 100 music teachers

The point here is that there’s so much nuance that goes far deeper than even just knowing whether someone is a client-facing advisor or not – which we often don’t even know in the first place because that’s not even a field in the publicly available Form U4 data!

Perhaps what we need more than anything is a very logical foundation for what we’re doing as researchers (or as consumers of research).

Let’s go back to the CFP professional misconduct example. Part of the reason that these findings might (but hopefully won’t) get some traction in the media is that they’re surprising. We think, “CFP professionals engage in more misconduct? I would have expected the opposite.”

But at least until the studies in this area get much better, we probably should be relying a bit more on our gut instincts when we hear about these studies. Does it really make sense that CFP professionals –individuals who voluntarily subject themselves to further education, testing, and ethics requirements – would engage in more misconduct, all else being equal?

No, it doesn’t. That’s not to say that it couldn’t be true. Of course, we should remain open to having our views changed by evidence, but we should start with a pretty strong prior that, on average, the types of professionals who self-select into pursuing CFP certification are probably not more likely to engage in misconduct than other advisors.

However, that’s certainly not to say that there might not be some subsets of advisors who do seek out the CFP marks with intentions to engage in misconduct. Certainly, one could try and use CFP certification as a means to get someone’s guard down and could pursue the designation with ill intentions. This individual is going to be relatively rare, but a proper nuanced understanding of the relationship between CFP certification and advisor misconduct shouldn’t overlook the possibility that some could seek out the CFP marks with bad intentions.

Minimum Expectations For Trustworthy Research On Advisor Misconduct

Unfortunately, I am not optimistic that the state of this research will really improve anytime soon. FINRA has not shown any inclination to add a field to Form U4 for registered individuals to indicate whether they’re really client-facing advisors or not. And big data is just too in vogue where, for an academic researcher, it sounds really attractive to be able to publish a study based on “all securities-licensed professionals”. But there are at least some things we can look for that should begin to move this research forward.

First, at an absolute minimum, studies analyzing financial advisors should be able to demonstrate that they have some method of discerning who even is a financial advisor and who is not. These methods will never be perfect – even the data vendors will be relying on imperfect methods – but any study that reports it is based on 600,000+ “advisors” (FINRA-registered individuals) can almost immediately be disregarded. If that claim is made, a study is not actually looking at advisors because there simply aren’t nearly that many in total in the first place.

The simplest way to address limitations like this is for researchers to work with companies like Discovery Data to at least get some enrichment that indicates who has been identified as a client-facing advisor versus who has not.

Second, studies should be grounded strongly in theory and logic. The Tharp et al. misconduct study demonstrates exactly how the relationship between CFP certification and misconduct could flip by limiting the sample to just advisors and introduces additional control variables such as age, gender, IAR status, insurance status, etc. Particularly when studies include all sorts of non-advisors in the analysis, we’re going to see those traits that simply are just traits of advisors will themselves be associated with misconduct. However, we can get a much better understanding here by just thinking critically and logically about whether a ‘surprising’ result is really a new discovery, or just a tacit recognition of a flawed methodology in identifying who is really a financial advisor in the first place.

Third, we should be slow to demonize anyone (or trust studies that demonize anyone) when other factors may remain unaccounted for that could explain a relationship. This could become particularly germane in thinking about different types of business models.

For instance, if an advisor is going to work with truly middle- or lower-class Americans (and not just the top 10% of Americans that previous Kitces Research has indicated most financial advisors target), then the simple reality of that business model is that the advisor will need to work with more clients than an advisor working with deca-millionaires. The truly middle-class advisor might have to try and work with 200–250 clients. That will inevitably mean fewer touchpoints per client and weaker client relationships. Not only does that raise the risk that there might be some sort of oversight, but the weaker client relationship could leave a client more likely to file a complaint than call the advisor to talk through their concerns. By contrast, if an advisor works with only 30 clients, who they know incredibly well and touch base with at least monthly, the risk that something falls through the cracks is lower, and the likelihood that a client jumps straight to filing a complaint (rather than asking for a resolution directly from the advisor first) is likely lower.

Which means you could likely take the exact same advisor and put them in these 2 different contexts, and over the course of their career, an advisor would be far more likely to generate a misconduct record working with 200-250 clients, even if they were every bit as ethical and trying just as hard to not make any mistakes.

Another consideration, and something that, in my opinion, Camarda has done a commendable job with, is trying to look more specifically at what “misconduct” actually means. In his dissertation, Camarda developed various measures of misconduct ranging from misconduct that is least concerning from a consumer perspective (e.g., merely an allegation of non-advisory related misconduct) to the most concerning (e.g., advisory-related misconduct with clear evidence of culpability). If we’re thinking in terms of truly protecting consumers, Camarda’s more strictly defined measures of culpable advisory-related misconduct are good examples of standards other researchers should be striving for.

But ultimately, the main point is to be very careful when interpreting claims such as the claim that CFP professionals are more likely to engage in misconduct. While these types of findings naturally will garner some headlines, we should be aware that these types of findings can be expected when we’re trying to study “financial advisors” using data sets of FINRA-registered individuals that include 300,000+ non-financial advisors.

Leave a Reply