Executive Summary

The FPA Residency program (originally the ICFP Residency program) was created to help financial planners develop the skills needed to be successful through the use of on-site case studies to gain practical experience guided by a group of peers and a mentor as a guide. Over the years, this program has been a valuable experience for many advisors who have had the opportunity to attend. However, the intimate nature of the event naturally means that many advisors have not had an opportunity to attend, and therefore have not had the opportunity to learn from this event.

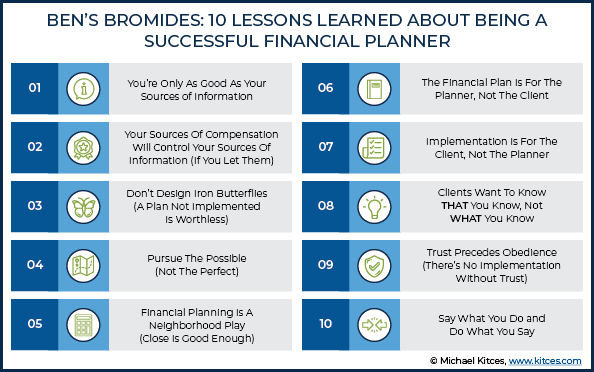

In this guest post, Ben Coombs, a veteran mentor of the FPA Residency program and a member of the very first graduating class of CFP certificants in 1973, shares 10 underlying "truths" – wise lessons he learned about being a (better) financial planner – that he developed as an attempt to capture the core values of Residency.

In the Residency program, Ben's 10 truths became to be known as "Ben's Bromides", and include lessons covering many important insights – from lessons regarding the information we provide to clients (e.g., you are only as good as your sources of information, and your sources of compensation will control your sources of information), to lessons about what we should do as financial planners (e.g., don't design "iron butterflies", and pursue the possible), to lessons about how we should put together a plan (e.g., financial planning is a "neighborhood play", and remembering that the financial plan is for the financial planner – not the client!). And while these lessons core values were first taught and developed for FPA Residency, Ben's Bromides capture a lot of financial planning wisdom in a concise manner that is useful for any and every financial planner!

Thoughts To Guide Your Professional Activities

The FPA Residency program (originally the ICFP Residency program) was created to provide newer advisors with practical experience in working through “real” financial planning scenarios (on-site case studies) with a group of peers and a mentor as a guide. As the program grew, though, I wanted to help ensure that all the mentors and residents had a common focal point or orientation as to the core values of residency.

Out of that concern, I set out to espouse a set of truths that we could hold out to everyone in attendance.

What emerged were 10 underlying “truths” for financial planning professionals, which were dubbed “Ben’s Bromides” for the soothing effect they had on those nervous new advisors at Residency… and which I share with you today, in the hopes that you find them helpful as well!

You’re Only As Good As Your Sources Of Information

Information is power. It is one of the things that set you apart from your competitors. As a result…

- Carefully choose your sources of information to be sure they expand on each other and are not redundant. It is easy to keep hearing the same thing in different forms, and be led into thinking you are getting new information, instead of the same information repackaged.

- Understand the biases of the source of information, because biases slant the information to suit the bias. All information comes slanted by bias. Your job is to understand the bias, so you can filter it out.

- Information is not wisdom. Wisdom is needed when you apply or use the information. Wisdom comes from experience. Most importantly, however, it comes from caring. Wisdom resides in the heart, not the head.

So, be hungry for information that amplifies your professional capacity, that is filtered for biases and apply it with wisdom.

Your Sources Of Compensation Will Control Your Sources of Information (If You Let Them)

There is a strong and insidious tendency on the part of all of us to want to learn more about those things that butter our bread. If we are compensated by commissions, we tend to want to learn more about the proper and effective use of those products that generate our commissions. If we are compensated by asset management fees, we tend to want to learn more about the proper management of investment assets.

The danger is that we will begin to concentrate our information seeking to the point we are not spending enough time learning about all the other things that are important to our role as a financial planner. This bias also affects the selection of topics and speakers at the various meetings we attend. Sponsorship money affects the information offered and the selection of speakers.

Be careful to get out of the information box created by your source(s) of compensation. Be careful to select programs to attend that are not all sponsor supported or, at least, select ones that have a wide variety of sponsors.

Don’t Design Iron Butterflies

You know a great deal about all the myriad of things that could possibly be used to improve your client’s financial situation. You could develop a wonderful plan for your client to follow that would produce glorious results through multiple generations. But it may not fly because your client may not implement it.

That’s an Iron Butterfly. It looks pretty but it won’t fly. A plan that is not implemented is worthless.

There are all sorts of reasons why a client won’t implement your plan and recommendations. Perhaps it is too complex for the client to understand. Perhaps you have asked your client to do something that looks like something the client has done before with disastrous results. Perhaps the client’s other advisors or family members don’t agree with your recommendations, and the client is getting mixed signals.

Your fact-finding isn’t complete unless or until you know as much about the client as you know about the client’s circumstances. You need to know three things about every client:

- Where the client wants to go (goals).

- Where the client is today (the hard data), and

- What the client is willing to do to get from here to there (the soft facts).

Unless you concentrate on the latter, you run the risk of designing Iron Butterflies.

Pursue The Possible

Not the perfect. This is related to the Iron Butterfly. A financial plan is a “living” document. It is also a road map for a journey. And, as you know, a journey begins with the first step.

Action is the most important aspect of a financial plan. It is likely that, as a professional and insightful financial planner, you know what is THE most important thing for the client to get done – first.

But the client may not be ready to take that first step first. Again, you need to work with the confines of what the client “is willing to do to get from here to there”.

So rather than insisting that the client do first things first, allow them to do what they are willing to do to the extent it gets them closer to their goals, and doesn’t work against doing the other more important things you have recommended. Taking the possible actions will ultimately lead to taking the perfect actions.

Financial Planning Is A Neighborhood Play

An HP 12C calculator will calculate an answer out to 7 or 9 decimal points. But what is the point?

As computers get more sophisticated, thereby allowing us to analyze everything from every possible angle, we tend to get caught up in the elegance of our solutions (Iron Butterflies) and the precision of our analysis. But remember two things:

- No matter how precise your answer or calculation maybe it will be wrong tomorrow; a moment will change everything and

- You can’t send a rocket to the moon without making mid-course corrections.

Think of the double play in baseball. The second baseman or shortstop only has to be in the neighborhood of the bag for the umpire to call the runner out. You only have to be in the neighborhood of the precise answer.

So, don’t spend precious resources, running up client fees and your expenses, just to get a precise answer that will be wrong tomorrow. It is called Analysis Paralysis.

The Financial Plan Is For The Planner, Not The Client

It is a common problem of our profession to view the financial plan nicely housed in an elegant binder as our work product. The client pays good money to get us to this point, so they deserve a richly appointed work product. BUT… that is not what they want.

They want to know that you know what you need to know to advise them effectively. They want to know that you asked all the right questions and HEARD their answers.

Often the plan we deliver only proves to them that we know a lot, but because of its size and complexity, the client isn’t sure that we HEARD everything they told us. The trusting ones will assume that in amongst all that manure there must be a pony somewhere. Others will just be put off by the volume of volumes we deliver to them.

The plan document that we deliver must communicate that we LISTENED TO and HEARD the client. It must communicate that we know. Beyond that, it is for us. We need a framework for evaluating the impact of recommendations and measuring progress and change in the future. The plan is for the planner.

Implementation Is For The Client, Not The Planner

However, the implementation of the plan is for the client. And just as our compensation can affect our sources of information it can affect the implementation of the plan – if we let it.

The fact that we get paid more, or only, if the client implements some parts of our advice and not others, should not (but sometimes does) affect which of our recommendations we cause to be implemented first, or with the most follow through. Perhaps new wills and a trust is THE most important things that need to get done immediately because the client has terminal illness or is leaving on a long trip (just to make my example stark). But if we pursue the setting up the client’s managed account most diligently, while not bothering to pester the attorney who doesn’t return our phone calls, we have failed the client, even though both recommendations were good and proper.

Implementation priorities need to be client driven, not compensation driven.

Clients Want To Know THAT You Know, Not WHAT You Know

This has been touched upon already, but let’s expand on it.

As pointed out before, the financial plan shouldn’t be a device to show off how much we know. Neither should we inform or teach the client more than the client has the capacity to digest and understand. The client needs to understand enough to make informed decisions, but not enough to become a CFP certificant themselves.

We need to be sure that the client understands. So, tell a little, and ask questions to determine understanding. Then tell a little more, and ask again. When you get to the point that you feel the client understands the trade-offs and implications of the decision that is being made, you have informed enough.

Telling without asking questions to determine understanding, and telling more than is needed for informed decision making, is just showing off.

Trust Precedes Obedience

What we are looking for in clients is informed obedience. We are not looking for YES people.

If a client isn’t implementing close to 80% of your recommendations, then there are probably barriers to your communications and your relationship with the client.

One of those barriers is a lack of trust. A lack of trust can come from not listening, or not hearing the between the lines communication the client is sharing with you. A lack of trust can come from confusion and obfuscation created by too much information and too much complexity. A lack of trust can come from asking the client to do things they are not comfortable with, or others who are impacted by their actions are not comfortable with. A lack of trust can be the problem because it was never established, or it was lost. Without trust, you don’t have a client, or will soon lose them.

The best way to measure the presence of trust is to ask questions about their understanding and acceptance of the recommendation. But the best measure is following through on the part of the client. If it is not there, trust is probably not there.

Say What You Do and Do What You Say

Be congruent. Walk the talk and talk the walk.

The greatest source of incongruency we have in our profession is between what we say we are and will do for clients, and our form of compensation.

Whether you receive fees or commission, or both, is not the problem. There is incongruency in all forms of compensation. Typically, our planning fees are loss leaders for commission and/or asset management fees. As a result, we must get paid commissions and/or asset management fees, which can distort our focus.

We need to understand our conflicts of interest (we all have them), and be fully conscious of them. Awareness and a committed desire not to be pushed around by your conflicts of interest will go a long way toward overcoming or avoiding the potential problems stemming from the conflicts.

There is no pure form of compensation. If you are paid hourly your conflict is with running up the hours or working on non-billable activities. If you are paid commissions or asset management fees, your conflict is between focusing on those implementation actions that lead to commissions or asset management fees, as opposed to actions that don’t.

So be aware of your conflicts. Be committed to protecting against them. And be willing to fully disclose (full details) and discuss them with your clients up front, and often, and at your initiative.

So what do you think? Do you think advisors are only as good as their sources of information? Have you ever designed "iron butterflies"? What suggestions do you have for achieving success as a financial advisor? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply