Executive Summary

After months of anticipation with a ‘two-track’ process of infrastructure and separate tax legislation, Democrats on the House Ways and Means Committee released their tax proposals on September 13… and the measures are very different from what many expected! The legislation touches on a wide range of tax issues, from increasing the top ordinary income tax bracket to cracking down on popular retirement account strategies and bringing the estate and gift tax exemptions back to pre-2017 levels. Notably, though, the proposals do not include some rumored measures, such as equalizing the top ordinary income and capital gains rates or eliminating the step-up in basis. While the legislation will now be debated in Congress and finalized in the weeks to come, these proposals will create a range of planning opportunities for advisors to consider both in the future… and to take action before the legislation is signed and certain planning windows are closed!

As originally proposed by the Biden administration in its American Families Plan, the bill includes a host of new tax increases on households earning more than $400,000. In addition to restoring the 39.6% top marginal rate (which was reduced to 37% by the 2017 Tax Cut & Jobs Act), the legislation also increases the top capital gains rate to (only) 25%, although it lowers the amount of income needed to get into the top tax bracket (for both ordinary income and capital gains) to only $400,000 (for individuals, or $450,000 for married couples). As a result, the taxpayers who will be most impacted by the new rates are those in the $400,000–$500,000 income range, who will see themselves move from the current 35% bracket to the new 39.6% bracket – as higher earners who were already in the 37% bracket will see ‘only’ a 2.6% increase to 39.6%. Other changes targeting higher earners include a limitation on the Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI), an expansion of the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) impacting S Corporation owners, and a 3% surtax for ultra-high earners with over $5 million of income (making the true top tax rate 42.6%).

Another main focus of the bill is reforming retirement plan rules to close perceived “loopholes” commonly used by wealthy individuals. Perhaps most relevant for financial planners and their clients is the bill’s aim to eliminate the ‘backdoor’ Roth strategy, prohibiting Roth conversions of after-tax funds in retirement accounts altogether, as well as prohibiting all Roth conversions for those in the top income tax bracket (but only after a 10-year window, subtly encouraging high-income taxpayers to convert to Roth accounts – and pay taxes – sooner rather than later). Also notable are two new rules for high-income taxpayers with more than $10 million of aggregated retirement account assets: a prohibition on making new IRA contributions, and a new Required Minimum Distribution of 50% of the combined balances above $10 million (and 100% of combined balances above $20M), forcing dollars out of large retirement accounts. However, these forced-distribution rules only kick in for taxpayers in the top tax brackets, meaning those who are able to reduce or shift their income will still be able to contribute and accumulate retirement savings above and beyond the $10 million cap.

The proposed bill also contains significant reforms to estate law, most notably a 50% reduction in the estate and gift tax exemption – while simultaneously increasing the special valuation reduction for real property used in family farms and businesses from $750,000 to $11.7 million. The bill also cracks down on Intentionally Defective Grantor Trusts (IDGTs) by including those trusts’ assets in their grantors’ estates. In addition, any sale between an individual and their own grantor trust will be treated as the equivalent of a third-party sale, and any transfers out of a grantor trust will be considered a taxable gift. Family Limited Partnership discounts would be similarly curtailed as nonbusiness assets – including stocks, bonds, options, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) or mutual funds, and trademarks – would no longer be eligible for valuation discounts (though any remaining bona fide business assets would still be eligible for a minority and marketability discounts as appropriate).

Ultimately, while some of the proposed changes may require large pivots to be made by advisors and clients, it’s worth remembering that this bill is not yet in its final form – there may still be weeks of negotiation before it is passed. That said, advisors should be prepared to act quickly, as many of the major proposals in the legislation are set to go into effect on January 1, 2022, and some will take effect as soon as the legislation is enacted… which may leave just weeks or even days to act if Congress proceeds!

*** Editor’s Note: Additional information will be added to this article in the coming days. Please check back for updates.

When the Biden administration released its American Families Plan in April, many saw its proposed changes to the tax code as a starting point for a long negotiating process on the journey to becoming law. While it was almost certain that there would be changes to the plan’s features, what wasn’t clear was how or where those changes would take place – in committee, on the legislative floor, or in reconciliation between the House and Senate.

The proposed legislation released by the House Ways and Means Committee on September 13 provides at least a partial answer to that question. While many of the features of Biden’s original plan are included – most notably raising income and capital gains tax rates on high earners – the number of differences between the original plan and the proposed bill indicates that much of the negotiation has already taken place, meaning that, if the legislation becomes law, its final form will likely be similar to the newly proposed version.

Which means that, even though the bill has yet to become law, it is important for financial planners and their clients to know what it contains, as individuals might now have only months, weeks, or even days to make decisions that could have an enormous impact on their financial lives. With the caveat that the final legislation could look different from the current proposal, it seems clear that we will be seeing some important changes, from income tax rates to rules surrounding retirement accounts to estate and transfer laws and more.

New (Again) Top Ordinary Income Tax Rate Of 39.6%

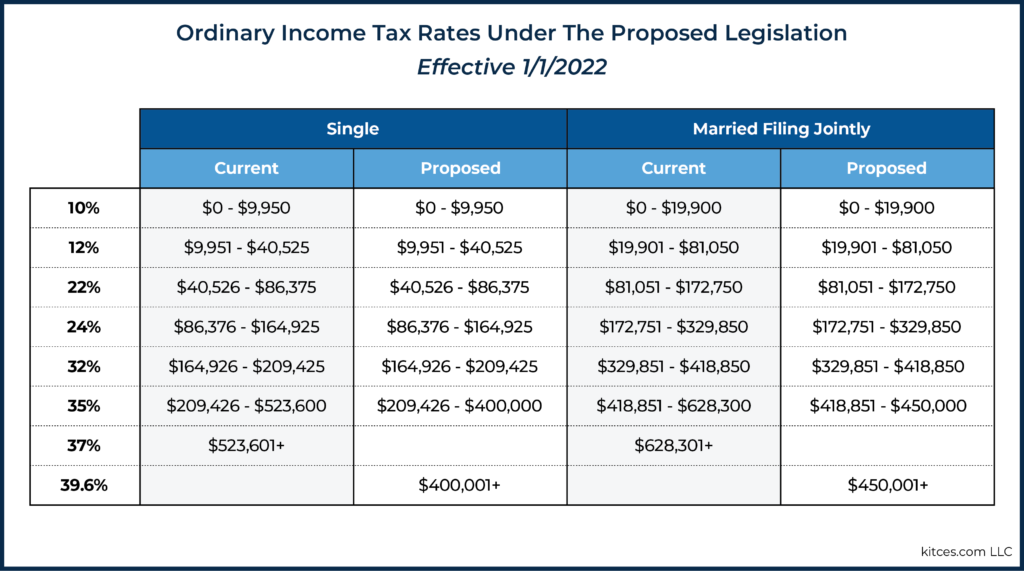

One of the centerpieces of the bill is a return of the top ordinary income tax bracket to 39.6%. 39.6% had been the top rate from 2013 through 2017, but was reduced to 37% beginning in 2018 with the enactment of the Tax Cuts And Jobs Act (of 2017). If enacted, the current bill would ‘permanently’ reinstall 39.6% as the top ordinary income tax rate, beginning in 2022.

But for some high-income taxpayers, other changes to the ordinary income tax brackets may actually be more impactful. That’s because the bill does not simply replace the current 37% bracket with the new 39.6% bracket, but rather, it also significantly lowers the amount of income a taxpayer can have before finding themselves in the top tax bracket!

More specifically, whereas the current 37% top ordinary income tax bracket does not ‘kick in’ for married taxpayers filing joint returns until they have more than $628,300 of taxable income in 2021, the bill would impose the top ordinary income tax rate of 39.6% on joint filers at ‘just’ $450,000 of taxable income in 2022. Similarly, whereas the current 37% ordinary income tax bracket does not begin to impact single filers until they have more than $523,600 in 2021, the top rate of 39.6% would be applied to taxable income in excess of $400,000 for the same filers in 2022.

As can be seen in the chart above, the lower income thresholds ($400,000 for Single taxpayers; $450,000 for Married Filing Jointly taxpayers) at which the top rate begins, results in the current 35% ordinary income tax bracket becoming substantially compressed. Whereas the current 35% tax bracket range for single filers spans over $300,000 (from $209,426 to $523,600), the new 35% range would span about $200,000 (from $200,000 to $401,000). Married taxpayers see an even more dramatic squeeze of the 35% tax bracket range, with the current threshold spanning over $209,000 (from $418,851 to $628,300) and the new range of around only $50,000 (from $400,001 to $450,000)!

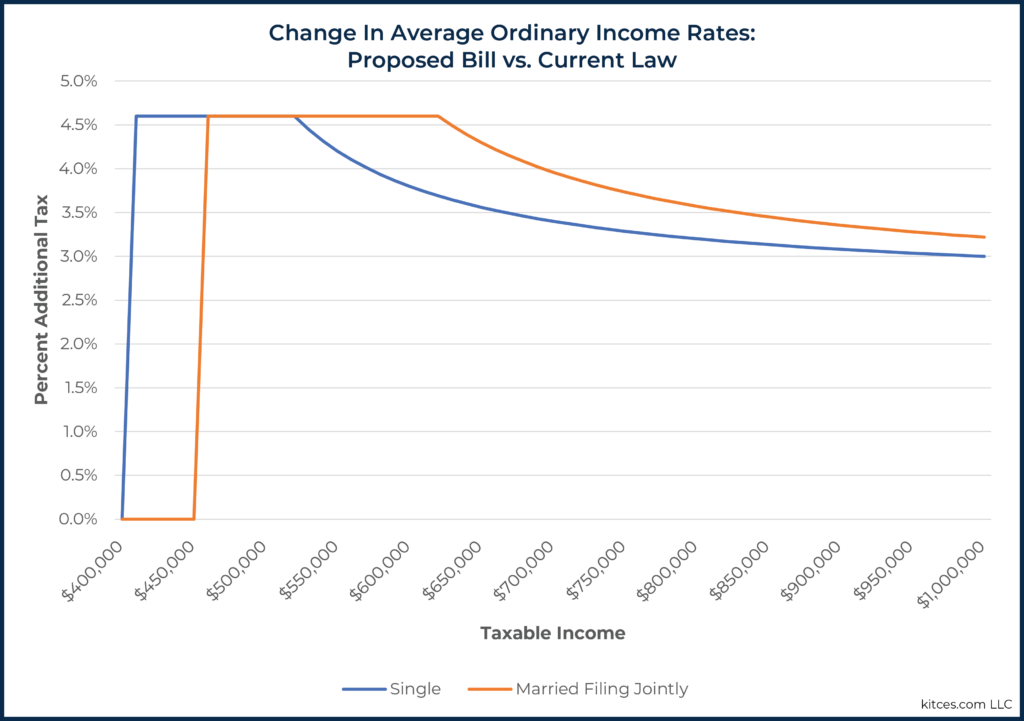

So, while it is certainly true that the greater a taxpayer’s income, the more the proposed change would increase their total tax liability, a reasonable argument could also be made that single filers with taxable income of over $400,000 and joint filers with taxable income of over $450,000 will see the most profound impact to lifestyle, savings, etc.

Notably, as illustrated in the chart above, such taxpayers would see the largest average increase in tax liability as a result of the change. This occurs because, while the greatest change in the current versus future proposed tax rate would occur where today’s 35% bracket becomes 2022’s 39.6% bracket (a difference of 4.6%), as total income continues to increase, more and more income that is taxed today at the current top rate of 37% would be taxed at 2022’s 39.6% bracket (a difference of ‘just’ 2.6%). Thus, the greater the income (at least until a taxpayer ‘hits’ $5M of AGI, as discussed later), the more the average increase in tax on affected income approaches 2.6%.

Nerd Note:

Those with the highest increase in average tax rates may benefit the most from accelerating income into 2021.

New Top Long-Term Capital Gains Rate (As Of September 14, 2021)

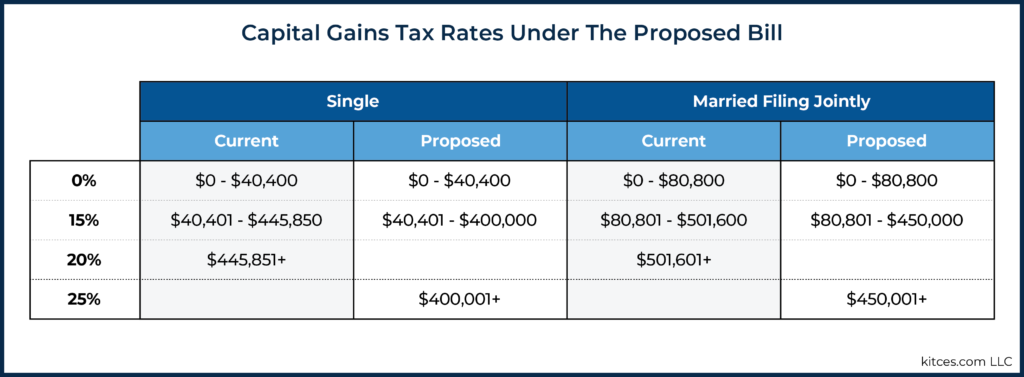

Paired with the new top ordinary income tax rate is a new top long-term capital gains rate of 25%. Critically, unlike the proposed change to ordinary income tax rates, which would not be effective until 2022, the proposed changes to the top long-term capital gains rate would go into effect immediately, impacting long-term capital gains incurred on or after September 14, 2021.

Thus, taxpayers with large unrealized capital gains would not be able to sell such assets before the end of the year in order to avoid the higher rate.

That said, a narrow but important exception is included in the proposal that would exempt gains from certain existing binding contracts from the higher 25% rate. To qualify for the exception, the binding contract must:

- Have been entered into on or before by September 13, 2021;

- Be in writing;

- Cannot be modified (after September 30, 2021) in any “material respect”; and

- Close before the end of the year (the sale must occur in 2021).

To the extent that a contract satisfies these requirements, the gain will be treated as having occurred prior to September 14, 2021, and thus, would be subject to the old(?) maximum long-term capital gains rate.

The proposal also aligns the income threshold for the top long-term capital gains rate with the income threshold for the top ordinary income tax rate. More specifically, the top long-term capital gains rate of 25% will take effect (up from 15%) at the same threshold ($400,000 for single filers, $450,000 for married filing jointly) at which the 35% ordinary income tax bracket becomes the 39.6% ordinary income tax bracket.

For 2021, gains incurred as of September 14, 2021 and later would be the last to be ‘layered’ onto a taxpayer’s income.

Example 1: Darryl is a single taxpayer who, after accounting for all income and deductions, has $470,000 of taxable income for 2021, which consists of $380,000 of ordinary income, $50,000 of long-term capital gains attributable to sales completed prior to September 14, 2021, and $40,000 of long-term capital gains attributable to sales completed on and after September 14, 2021.

When calculating Darryl’s tax liability for the year, his ordinary income will be counted first. Next, his long-term capital gains from prior to September 14, 2021 will be factored in. Thus, he will owe a 15% rate on the first $20,000 of those gains, and a 20% rate on the remaining $30,000 of gain. Finally, all $40,000 of the gain from September 14, 2021 and beyond will be subject to the new 25% top rate.

Nerd Note:

The 25% rate would be the highest top rate imposed on long-term capital gains since the middle of 1997. As a result of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, long-term capital gains incurred prior to May 6, 1997, were subject to a maximum long-term capital gains rate of 28%, while long-term capital gains incurred on or after May 6, 1997, were subject to the newly introduced maximum long-term capital gains rate of 20%.

Application Of The 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) To High-Income S Corporation Owners

Under current law, profits of S corporations are subject to neither employment taxes (e.g., FICA taxes, Self-Employment Tax), nor the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). While not exclusive to S corporation profits, this ‘dual exemption’ puts profits in a narrow group of income sources, which are able to avoid both types of taxes (distributions from retirement accounts would be another good example!).

If enacted, the proposal would change that for certain high-income S corporation owners. More specifically, once an S corporation owner’s Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) exceeds their applicable threshold, S corporation profits will be added together with ‘regular’ investment income to produce something the bill calls “Specified Net Income.” And ultimately, the greater of a client’s net investment income or Specified Net Income will be subject to the 3.8% surtax.

The applicable thresholds are as follows:

- Single filers – $400,000

- Joint filers – $500,000

Thankfully, unlike many other thresholds in the bill, these are not ‘cliffs.’ Rather, a phase-in range of $100,000 ($50,000 in the case of married taxpayers filing separate returns) will help some taxpayers with higher income from seeing the full amount of their S corporation profits becoming subject to the surtax. The phaseout works by preventing an increase in the 3.8% surtax liability, due to the inclusion of S corporation profits, that is greater than the percentage of the phase-in range they have ‘used.’

For instance, if a taxpayer has MAGI that puts them 40% through their phaseout range, then their 3.8% surtax can be increased, due to the inclusion of their S corporation profits, by no more than 40% of the amount it would be increased if all such profits were included.

Together with the change in the top ordinary income tax bracket, this change increases the top rate for high-income S corporation owners from 37% to 39.6% + 3.8% = 43.4%!

Example 2: Angela is a single, high-income S corporation owner. In 2022, she anticipates MAGI of $530,000, of which $300,000 will be attributable to S corporation profits and $20,000 will be attributable to ‘regular’ investment income.

Here, Angela’s $300,000 of S corporation profits will be added to her $20,000 of ‘regular’ investment income, giving her $320,000 of “Specified Net Income”. Furthermore, since Angela is $330,000 over the $200,000 MAGI threshold for the 3.8% surtax applicable to single filers, all $320,000 of her Specified Net Income (the lesser of her $320,000 of Specified Income, and the $330,000 of her MAGI that is in excess of her applicable 3.8% surtax threshold) is potentially subject to the 3.8% surtax.

Finally, since Angela’s total MAGI of $530,000 is above the upper end of her phase-in range, all $320,000 of her Specified Net Income (which includes all $300,000 of her S corporation profits) will actually be subject to the 3.8% surtax. Thus, she will have a total NIIT liability of $320,000 x 3.8% = $12,160.

The following example illustrates how a taxpayer’s MAGI falling within the phase-in range must be treated to determine the impact of NIIT.

Example 3: Recall Angela, from the example above, who is a high-income S corporation owner. Suppose, now, that Angela’s business is less profitable than expected in 2022, resulting in $430,000 of MAGI, of which $200,000 is attributable to S corporation profits and $20,000 is attributable to ‘regular’ investment income.

Here, Angela’s $200,000 of S corporation profits will be added to her $20,000 of ‘regular’ investment income, giving her $220,000 of “Specified Net Income.” Furthermore, since Angela is $230,000 over the $200,000 MAGI threshold for the 3.8% surtax applicable to single filers, all $220,000 of her Specified Net Income (the lesser of her Specified Income and ($220,000) and her MAGI in excess of her applicable 3.8% surtax threshold ($230,000)) is potentially subject to the 3.8% surtax.

This time (as compared to the previous Example 2), however, Angela's $430,000 of MAGI puts her squarely within her phase-in range of $400,000 - $500,000. As result, an additional step is needed to determine how much of Angela’s income will actually be subject to the NIIT.

More specifically, if all of Angela’s S corporation profits were included in the calculation of the 3.8% surtax (as was the case in the previous example), Angela’s surtax liability, due to the inclusion of that income, would have increased by $200,000 x 3.8% = $7,600. However, since Angela is ‘only’ 30% of the way through her threshold, her S corporation profits can only increase her NIIT tax liability by a maximum of $7,600 x 30% = $2,280. Altogether, Angela would have $2,280 plus 3.8% x $20,000 of ‘regular’ investment income = $3,040 of NIIT subject to the 3.8% surtax.

The examples above illustrate a critical planning point for S corporation owners with MAGI within or close to the phase-in range. Should this provision be enacted as written, the phase-in range could result in a spike in the marginal rate significantly higher than the ‘stated’ top rate of 39.6%.

Notably, as a taxpayer’s MAGI goes from below their applicable phase-in range to above their applicable phaseout range, all of their S corporation profits go from exempt from the 3.8% surtax to losing their preferred status. So, while the phase-in range may be equal to $100,000 for most filers, adding $100,000 of MAGI can result in much more than $100,000 of S corporation profits becoming subject to the surtax.

Consider, for instance, that in example 3, above, Angela was only 30% of the way through her phase-in range. As a result, only a fraction of S corporation profits were subject to the NIIT, producing a liability of ‘only’ $2,280 (on those profits, plus another $760 in NIIT due to her regular investment income). But, in example 2, where Angela had ‘only’ $100,000 more of MAGI (due to $100,000 of additional S corporation profits), she had $300,000 of S corporation profit subject to the same tax, and had a total NIIT liability of $300,000 x 3.8% = $11,400 attributable to those profits. Thus, the additional $100,000 profits (led to an increase in income of $100,000, which) led to an increase in her NIIT of $11,400 - $2,280 = $9,120. In effect, there was a 9.12% surtax applied to the additional $100,000 of profits (on top of the regular 39.6% top ordinary rate)!

New 3% Surtax For Ultra-High-Income Taxpayers

Section 138206 of the proposal would create a new 3% surtax on ultra-high-income taxpayers. The additional 3% rate would apply to individual taxpayers’ (in contrast to estate and trusts, discussed below) MAGI to the extent it exceeds $5 million. The $5 million threshold will apply to both single and joint filers.

Notably, by making this a surtax (technically referred to as a “surcharge” by the proposal) on MAGI, as opposed to simply creating a 39.6% + 3% = 42.6% top ordinary income tax bracket, two things are possible. First, from a technical perspective, taxpayers will not be able to use below-the-line deductions to reduce their exposure to the surtax. Second, it gives a bit of political cover/wiggle room for more moderate Democrats to say they only raised the top rate by 39.6% – 37% = 2.6%, while more progressive Democrats claiming ‘victory’ in raising the top rate on the ultra-wealthy by 2.6% + 3% = 5.6%.

Given the extraordinarily high threshold of $5 million, few individual taxpayers would ever be subject to the surtax. Nevertheless, taxpayers would want to pay close attention to once-(or few)-in-a-lifetime types of events, such as the sale of a large piece of property or business that could potentially (albeit temporarily) push them over the $5 million mark.

Additionally, while individual taxpayers would rarely find themselves subject to the surtax, the same would not be true of all trusts, where the 3% surcharge would apply to trust income in excess of $100,000. And, while given today’s low-rate environment (requiring a substantial amount of assets to generate $100,000 of income via interest and dividends), capital gains would also be subject to the surtax.

Furthermore, to the extent a trust is the beneficiary of a retirement account, it may receive substantial amounts of income annually in the form of distributions from the account (especially when the new 10-Year Rule created by the SECURE Act applies!).

Creation Of A Cap on The Maximum Amount Of A Taxpayer’s QBI Deduction

When President Biden ran for office, part of his tax platform included the goal of eliminating the QBI deduction for taxpayers with income in excess of $400,000. Section 138204 of the proposal takes a slightly different tack on curbing the value of the deduction for high-income taxpayers, but one that will come as welcome news for many business owners.

More specifically, instead of eliminating the deduction altogether for taxpayers with income in excess of $400,000, the bill would simply cap the maximum amount of the deduction a taxpayer can claim. The maximum allowable QBI deductions would be as follows:

- Single filers – $400,000

- Joint filers – $500,000

- Trusts and estates – $10,000

To be clear, a taxpayer’s income would have absolutely no impact on the maximum available deduction. Rather, regardless of income, once the deduction reaches the maximum amount, additional amounts will be disregarded.

Of note, all other QBI deduction rules would remain unaffected.

Nerd Note:

This limitation only really impacts owners of Non-Specified Service Trade or Businesses (Non-SSTBs). No QBI deduction is allowed for single (filer) Specified Service Business owners once their income exceeds $214,900, and for joint filers of the same businesses once their income exceeds $429,800. But it takes dramatically more income than that to produce QBI deductions equal to the maximum amounts proposed by the bill.

Prohibition On Conversions Of After-Tax Amounts

If enacted, Section 138311 of the proposal is going to break some hearts. The provision would prohibit conversions of after-tax dollars held in retirement accounts (both IRAs and employer-sponsored retirement plans, such as 401(k)s), beginning in 2022.

As a result, popular strategies such as the “Backdoor Roth IRA,” and the even more powerful “Mega-Backdoor Roth IRA,” would become a thing of the past.

If this provision is enacted (which seems likely), it would create a need for a fresh look at the convert-or-not decision for savers with after-tax dollars in retirement accounts. While such individuals, particularly IRA owners (where the pro-rata rule applies), may have been waiting for the optimal time at which to make a conversion, the choice may soon be now or never (at least with respect to the after-tax dollars in their account).

(Future) Prohibition On Conversions For High-Income Taxpayers

For high-income taxpayers, Section 138311 goes beyond simply banning the conversion of after-tax amounts. Rather, for taxpayers with Adjusted Taxable Income (yes, yet another ‘type’ of income to keep track of) in excess of an applicable threshold, it would prohibit Roth conversions altogether. But not right away…

Whereas most of the proposals in the bill designed to curtail various practices by high-income taxpayers would go into effect beginning in 2022 (and some even sooner, such as the change in the top capital gains tax rate), the prohibition on conversions for high-income taxpayers would not take effect until 2032.

Nerd Note:

If you’re wondering, “Why in the world would they delay the effective date so long for something they clearly want to ban?”, the answer is simple. As the popular expression goes, “Follow the money!” By keeping Roth conversions up for high-income taxpayers on the table for another decade, legislators can count on the income from those conversions for budget projections (which, not coincidentally, go out 10 years).

The prohibition would apply to taxpayers with Adjusted Taxable Income in excess of the following thresholds:

- Single filers – $400,000

- Joint filers – $450,000

Per the bill, Adjusted Taxable Income would be equal to Taxable Income, plus any deduction for contributions made to an IRA, less any required minimum distributions due to high income/total retirement account funds (more on this below). Critically, these thresholds appear to be cliff thresholds, meaning just a single dollar too much, and the ability to convert is completely eliminated.

Nerd Note:

I may have missed it, but I didn’t see anything on backing out Roth conversion income from the Adjusted Taxable Income Amount. If that is, indeed, the case, then making a Roth conversion could push you over the income limit to make a Roth conversion?

Nerd Note:

The ability to recharacterize a Roth conversion does not appear to be included in the bill. But what if a taxpayer has higher-than-expected income and is over the limit? How would they unwind the transaction? And if they couldn’t do so, does that mean the entire amount ‘converted’ would have to be distributed as an excess contribution?

New Required Minimum Distributions For Taxpayers With High Income And Mega-Sized Retirement Accounts

Section 138302 of the bill – for which we could very well have Peter Thiel to thank – would create new RMD requirements for individuals who have both high income and massive retirement accounts, regardless of their age, effective for 2022. Absent one or the other, this new provision does not apply. As Marvin Gaye and Kim Weston taught us, “It takes two, baby!”

Specifically, to the extent that an individual has both 1) high income, as defined using the Adjusted Taxable Income thresholds described above with regard to the prohibition on Roth conversions ($400,000 for single filers, $450,000 for joint filers); and 2) total retirement accounts worth more than $10 million, they will be subject to RMDs for the year.

Such distributions would be required regardless of the age of the account owner. For young owners (under age 59 ½) of mega-retirement accounts with high income, the law does provide one welcome benefit. The 10% early distribution will not apply to amounts distributed on account of this new requirement.

For individuals with between $10 million and $20 million in total retirement accounts, the amount of the RMD would be equal to 50% of total retirement account dollars in excess of $10 million.

Example 4: Consider the following taxpayers:

Stanley, a 42-year-old single taxpayer, has $17 million combined in IRAs, 401(k) accounts, and 403(b) accounts. His Adjusted Taxable Income is $500,000. Since his retirement account dollars are greater than $10 million, he will have a Required Minimum Distribution of 50% × ($17 million – $10 million) = $3.5 million.

Kelly, a 50-year-old single taxpayer, has $17 million combined in IRAs, 401(k) accounts, and 403(b) accounts. Her Adjusted Taxable Income is $300,000. Since her Adjusted Taxable Income is less than $400,000, she has no required minimum distribution for the year.

Robert, a 35-year-old single taxpayer, has $9.5 million combined in IRAs, 401(k) accounts, and 403(b) accounts. His Adjusted Taxable Income is $1 million. Since the combined value of his retirement account is less than $10 million, he has no required minimum distribution for the year.

Special Rule For Roth IRAs With High Income And Total Retirement Account Balances In Excess Of $20 Million

In general, Roth IRAs are not subject to Required Minimum Distributions during an individual’s lifetime. That would change, however, for high-income (as defined above) Roth IRA owners with total retirement account balances in excess of $20 million.

More specifically, prior to completing the 50% RMD described above, such individuals would first have to complete a separate RMD by distributing the lesser of their:

- Total balances in all Roth accounts (Roth IRAs, and Designated Roth Accounts, such as Roth 401(k)s, Roth 403(b)s, etc.); or

- The amount necessary to reduce total retirement accounts to $20 million

To the extent that an individual has both Roth IRAs and Designated (plan) Roth Accounts and is required to make a distribution as a result of the rule above, they must first distribute the funds from their Roth IRA. Only then can the (remaining) amount requirement to be distributed be satisfied by a distribution from Designated Roth Accounts.

This rule takes effect when (and only when) an individual owns a Roth account, has combined (traditional and Roth) retirement account balances over $20 million, and has income in excess of the Adjusted Taxable Income thresholds above. Individuals to whom the rule applies, then, effectively must take two RMDs: first, distributing from (only) Roth accounts as required by the ‘$20 million’ rule; then, based on what is remaining in all the individual’s retirement accounts after satisfying the first RMD, distributing from any (traditional or Roth) retirement accounts as required by the ‘$10 million’ rule described previously.

Example 5: Consider the following taxpayers:

Meredith, a single taxpayer with $500,000 of Adjusted Taxable Income, has $23 million combined in IRAs, 401(k) accounts, 403(b) accounts. She also has $5 million in Roth accounts, giving her a total of $28 million in total retirement accounts.

Since her combined retirement account dollars are greater than $20 million and she has Roth Accounts, prior to satisfying the 50% RMD rule, she must first distribute the lesser of her total Roth dollars or the amount necessary to bring her total retirement account balances down to $20 million. Here, the lesser of those two amounts is $5 million, the entire amount Meredith holds in Roth IRAs.

After distributing the $5 million of Roth money, Meredith would be left with $23 million in retirement accounts. Thus, she would then have to distribute an additional 50% x $13 million = $6.5 million to comply with the 50% RMD requirement for large balances.

Toby, a single taxpayer with $500,000 of Adjusted Taxable Income, has $18 million combined in IRAs, 401(k) accounts, 403(b) accounts. He also has $5 million in a Roth IRA, giving him a total of $23 million in total retirement accounts.

Since his combined retirement account dollars are greater than $20 million and he has Roth Accounts, prior to satisfying the 50% RMD rule, he must first distribute the lesser of his total Roth dollars or the amount necessary to bring his total retirement account balances down to $20 million. Here, the lesser of those two amounts is $3 million, as after such a distribution, Toby would be left with ‘only’ $20 million.

After distributing the $3 million of Roth IRA money, Toby would be left with $20 million in retirement accounts. Thus, he would still have to distribute an additional 50% x $10 million = $5 million to comply with the 50% RMD requirement for large balances, but would be able to choose the accounts from which that distribution could be satisfied.

Gabe, a single taxpayer with $500,000 of Adjusted Taxable Income, has $19 million combined in IRAs, 401(k) accounts, 403(b) accounts. He also has $4 million in a Roth IRA and $2 million in a Roth 401(k), giving him a total of $25 million in total retirement accounts.

Since his combined retirement account dollars are greater than $20 million and he has Roth Accounts, prior to satisfying the 50% RMD rule, he must first distribute the lesser of his total Roth dollars or the amount necessary to bring his total retirement account balances down to $20 million. Here, the lesser of those two amounts is $5 million, as after such a distribution, Gabe would be left with ‘only’ $20 million.

Furthermore, since Gabe has both a Roth IRA and Roth 401(k), he must satisfy the $5 million amount required to be distributed from his Roth accounts using Roth IRA funds. As such, he will have to completely distribute his $4 million Roth IRA. Afterwards, an additional $1 million must be distributed from his Roth 401(k) to bring his total retirement account balance down to $20 million.

From there, Gabe would still have to distribute an additional 50% x $10 million = $5 million to comply with the 50% RMD requirement for large balances, but would be able to choose the accounts from which that distribution could be satisfied.

Restrictions On New IRA Contributions For Taxpayers With High Income And Mega-Sized Retirement Accounts

Along with new requirements to distribute income from retirement accounts annually, Section 138301 of the bill would also prevent individuals with high income and mega-sized retirement accounts from making any new IRA contributions. More specifically, beginning in 2022, in any year in which 1) an individual’s Adjusted Taxable Income exceeds their applicable threshold ($400,000 for single filers, $450,000 for joint filers); and 2) their total retirement accounts are worth more than $10 million, they will be prohibited from making IRA contributions.

Notably, though, the same restriction does not apply to employer-sponsored retirement plans, such as 401(k) plans. In fact, the restriction doesn’t apply to SEP IRA or SIMPLE IRA contributions either!

“Defective” Grantor Trusts Eliminated

One of the thorniest issues under the Internal Revenue Code is determining the proper taxation of assets that are held in a trust. As on the one hand, the whole point of creating a standalone trust to own property – as distinct from an individual who owns that property outright – is that the trust is taxed as its own distinct entity, separate from the income (and potential estate) taxes that might apply to the original grantor of the trust. On the other hand, the opportunity to have a trust that is taxed separately from the original owner of the trust assets is rife with potential tax abuses, where affluent individuals shift assets to a trust in name, but not in substance, in order to benefit from the separate tax treatment without actually meaningfully relinquishing control of those assets to the trust in the first place.

To address this over the decades, Congress enacted a series of provisions that determine when a trust may still be treated as the original grantor’s for income tax purposes (known as the “grantor trust” rules under IRC Sections 671-678), and a separate set of provisions to determine when a trust may still be treated as the original grantor’s for estate tax purposes (IRC Sections 2031-2046, and in particular, IRC Section 2036 for transfers to trust with a retained interest, and IRC Section 2038 for transfers that are revocable).

However, the provisions that cause a trust’s assets to be treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes are not quite identical to the provisions that do so for estate tax purposes, creating the possibility of a trust that is a grantor trust for income tax purposes but not included in the grantor’s trust – which is colloquially known as a “defective” grantor trust. Except that, in practice, creating such defective grantor trusts is often done intentionally – with the aptly named “Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust” (IDGT) strategy – as a proactive strategy to shift assets (particularly growth assets) out of an estate for estate tax purposes, while still keeping the growth of the assets taxable for income tax purposes (which under Revenue Ruling 2004-64 meant the grantor could pay the trust’s income tax liability, diminishing their estate by the tax payment while creating what is effectively ‘tax-free’ growth of assets held in a trust outside of their estate, further accelerating the amount of growth shifted out of their estate over time!).

This was most commonly done by giving the trust the power to pay premiums on a life insurance policy on the life of the grantor (triggering grantor trust status under IRC Section 677(a)(3) without causing estate inclusion), a “substitution power” under IRC Section 675(4)(C) for the grantor to swap personal assets with trust assets of equivalent value, or the ability for the grantor to borrow from the trust without providing any security for the loan at a below-market interest rate (again triggering grantor trust status, under IRC Section 675(2), but without causing estate inclusion).

To curtail this strategy in the future, Section 138209 of the proposed legislation would alter the tax treatment of (Intentionally Defective) Grantor Trusts with the introduction of a new IRC Section 2901, which would automatically cause any trust treated as a grantor trust for income tax purposes to be included in the grantor’s estate for estate tax purposes (even if not otherwise included under IRC Sections 2036, 2038, or another section of the code)… effectively eliminating the entire concept of a “defective” grantor trust altogether, as in the future all grantor trusts would by definition be income- and estate-taxable to the grantor! In addition, the new IRC Section 2901(a)(2) would cause any transfers out of a grantor trust to a third-party beneficiary to be treated as a taxable gift of the ‘deemed owner’ (the grantor) for gift tax purposes.

In further extending the crackdown on IDGTs in particular, Section 138209 of the proposed legislation would also add a new IRC Section 1062, which would treat any sale between an individual and their own grantor trust as being the equivalent of a taxable sale to a third party (unless the trust is fully revocable… in which case it would have already been included in the grantor’s estate anyway under IRC Section 2038). This is distinct from the prior treatment for grantor trusts, which under Revenue Ruling 85-13 had permitted a grantor to sell assets to their grantor trust without any income tax consequences (treating it as a sale of the asset ‘to themselves’ since it was theirs for income tax purposes before and after the transfer anyway). Which would further curtail the popular IDGTs strategy of 'selling' a high-growth asset to the trust in exchange for a low-growth promissory note in order to shift the growth out of the grantor’s estate into the trust.

It’s also important to recognize that because the proposal would impact any grantor trust that is ‘defective’ for estate tax purposes, it will not only impact classic IDGT growth-shifting strategies, but any defective grantor trust. For instance, Irrevocable Life Insurance Trusts (ILITs) are also often structured as defective grantor trusts (in order to maximize the growth of assets used to fund the trust), and would need to be formulated differently (as non-grantor trusts) in the future. Expect further ripples in the estate planning world as other tax planning strategies that indirectly relied on defective grantor trust status for income tax benefits (e.g., paying the trust’s tax liabilities under Revenue Ruling 2004-64) or that funded such trusts with sales to the trust (under Revenue Ruling 85-13) will have to be structured differently in the future.

Notably, the elimination of the IDGT strategy is not entirely surprising; a potential crackdown by including (defective) grantor trust assets in the grantor’s estate was proposed as early as 2012 under President Obama. Nonetheless, the proposal now appears to be finally coming home to roost.

Fortunately, the effective date for the proposal is the date of enactment – which means any existing IDGTs would still be grandfathered. Only new trusts created after the date of enactment would be subject to the new less-favorable (estate-included) grantor trust treatment. However, the proposal also stipulates that any new additions to existing IDGTs would also become subject to the new rules (for any portion of the trust that was funded after enactment), which means even for those who have existing IDGTs that haven’t been fully funded with gifts or sales, the time is now to do so is now, before the proposal is passed! And for those who want to leverage IDGT strategies before the new rules take effect, it will be necessary to both establish and fund the trust before the legislation is enacted!

Reduction In The Unified Credit Amount For Estate And Gift Taxes

With the passing of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, roughly four years ago, the unified estate and gift tax exemption was doubled from (an inflation-adjusted) $5 million to $10 million, beginning in 2018. Although that change was scheduled to sunset automatically at the end of 2025, the proposed bill shifts forward that timeframe, reducing the exemption amount back to (an inflation-adjusted) $5 million for 2022 and future years (expected to be about $6 million in 2022 after inflation adjustments).

If enacted, the change would create a ‘do or die’ (or perhaps a ‘do or be sorry when you die’?) situation for taxpayers with estates larger (or projected to be larger) at death than the reduced estate tax exemption. In such situations, from a tax planning perspective, using as much of the current exemption amount to gift assets before the end of the year makes a lot of sense.

Indeed, ultra-high-net worth individuals have known this day would come (at some point) and many have likely already made peace with having to part with substantial portions of their wealth to reduce the future impact of estate taxes. For other taxpayers who have amassed enough assets to be considered ‘merely’ high-net-worth, however, the decision of whether to part with assets now, and if so, how much, will be a much more nuanced and difficult decision.

(Family) Limited Partnership Discounts Curtailed

One of the most popular – and controversial – estate planning techniques of the past two decades has been the transfer of assets to heirs using (discounted) Family Limited Partnerships. At its core, the basic concept is simply that a minority interest in a nonmarketable “family” business is something that a third-party buyer would not pay “full price” for; instead, they would reasonably expect a discount to own an interest in a family business that they did not control and had limited ability to (re-)sell. In other words, even if one owned 25% of a $4M business, if they couldn’t control the business, manage the business, compel distributions from the business, or readily sell their 25% stake in the business, they would probably pay something less than 25% x $4M = $1M… otherwise, they may as well reinvest into a more liquid $1M investment.

The caveat, though, is that in recent decades, the strategy of obtaining discounts on Family Limited Partnerships has been taken to extremes, beyond simply the classic scenario of an actual family business (e.g., a bona fide operating family business), and into the realm of families that would simply push all of their other more-liquid assets into a Family Limited Partnership, and then claim the whole was worth less than the sum of the parts because the partnership interest itself lacked control or marketability.

To address this, Section 138210 of the proposed legislation would add new provisions to IRC Section 2031 (regarding the valuation of assets for gift and estate purposes) to stipulate that when a private business interest is transferred (e.g., a Family Limited Partnership), there will be no discount available for any “nonbusiness” assets held in the business (though any remaining business assets would still be eligible for a discount).

In this context, “nonbusiness assets” are defined as any passive investment asset not used in the active conduct of a business, and includes a very wide range of investment assets, including cash (or equivalents), stocks, partnership or profit interests, bonds, options, forwards or futures (or similar derivatives), other commodities, foreign currencies, REITs or mutual funds, precious metals (not used in the business), annuities, assets that produce royalties (e.g., patents, trademarks, copyrights, etc.), collectibles, and real estate. Notably, though, accommodations are made for a reasonable amount of cash held as working capital in a(n otherwise bona fide) business, certain derivatives held for legitimate business purposes (e.g., farmers who hold commodities futures to hedge their actual crop exposure), and real estate that is part of an active real estate business in which the transferor materially participates.

In addition, where an entity has at least a 10% interest in another entity – e.g., a partnership that itself owns another partnership, LLC, or stock in another entity – a “look-through” rule stipulates that the holdings of the underlying entity (and its nonbusiness assets) are ratably attributed to the entity. Thus, for instance, if a Family Limited Partnership held a 25% interest in a second partnership that itself owned $2M of assets including $500k of nonbusiness assets, then the Family Limited Partnership would be deemed to own 25% × $500k = $125k of nonbusiness assets, for which the Family Limited Partnership would not receive any discounts.

Notably, because the proposed rules limiting discounts are all written specifically in the context of nonbusiness assets, bona fide businesses that are family-owned or otherwise privately held would continue to receive discounts (as is already common in the marketplace in practice). Only discounts attributable to the nonbusiness asset portion of the entity – generally in the form of investment assets held inside of the entity, not used for working capital, hedging, or other business purposes – would be limited. Which would not impair the discounting applicable to family businesses being transferred, but would effectively curtail the creation of Family Limited Partnerships simply to pool together investment assets for the sole purpose of trying to obtain a discount (even in situations where the family can otherwise claim a bona fide business purpose for the Family Limited Partnership… if it holds passive investments, the discounts will still be curtailed on that basis alone, because they are passive assets and not used in the active conduct of the business).

However, similar to the proposal on Grantor Trusts, the new rules limiting discounts would only become effective after the date of enactment. Which means that, for estate planning purposes, interested parties still have what may be a very limited time window to transfer (or establish and then transfer) Family Limited Partnerships holding passive investments at a discount before President Biden signs the legislation (in the days or weeks to come?).

Expanded Child Tax Credit Extended

On March 11th of this year, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan, which implemented a significant expansion of the Child Tax Credit, including increasing the credit amount from $2,000 to $3,000 (which itself was an increase from $1,000 to $2,000 under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017), further expanding it to $3,600 for children under the age of 6, making the credit a fully refundable tax credit (up from the prior TCJA limit of $1,400 refundable), and implementing a system of providing the Child Tax Credit as an advance monthly payment for families for the second half of 2021.

Under the proposed legislation, the current expanded Child Tax Credit is extended through 2025 in a 2-step process, where the current rules (from the American Rescue Plan in 2021) providing an annual Child Tax Credit with advance monthly payments are extended into 2022, and beginning in 2023 the Child Tax Credit is formally transitioning into a monthly child tax credit of $250/month/child ($3,000 per year per child) for children age 6 and older and $300/month/child ($3,600 per year per child) for each child under the age of 6.

Furthermore, under the new rules beginning in 2023, the requirements for a child to be eligible for a Child Tax Credit shift from the current “qualifying child” rules (i.e., must be a child of the taxpayer, with the same principal place of abode, who does not provide more than one-half of their own support) into new more flexible “specified child” rules (i.e., that the child has the same place of abode, is under age 18, is younger than – and not the spouse of – the taxpayer themselves, and “receives care” from the taxpayer, but without a specific requirement to provide less than one-half of their own support, and most significantly the taxpayer does not have to be a parent of the child, but could be another relative, or simply someone who is providing care for the child and otherwise meets the requirements).

In addition, the Child Tax Credit will remain fully refundable, and retains the income phaseouts of the American Rescue Plan (at $150,000 for married couples, $112,500 for Head of Household, and $75,000 for individual filers). Though the Child Tax Credit amounts themselves, and the income phaseouts, are indexed for inflation beginning in 2022. Beginning in 2023, the Child Tax Credit can only be partially phased out above these income limits; full phaseout begins for households with income above $400,000 (for joint filers; $300,000 for Head of Household, and $200,000 for single filers).

Dependents who do not meet the specified child rules will be eligible for a smaller $500/year tax credit, phasing out at the higher $400,000 / $300,000 / $200,000 phaseout thresholds.

Notably, to make the Child Tax Credit more accessible for those with more ‘volatile’ income, in 2022, the Child Tax Credit will be determined based on the lower of 2022 Adjusted Gross Income or 2021 AGI instead. And beginning in 2023, qualification for the Child Tax Credit is determined based on the lowest income from either the then-current tax year or the preceding two tax years. Furthermore, to the extent the Child Tax Credit is overpaid in monthly advances, it generally only must be repaid in cases of fraud, intentional disregard of the rules, or deliberate understatements of income (that were made in order to improperly qualify in the first place).

Wash Sale Rules To Apply To Additional Asset Types (Including Cryptocurrencies) And Individuals

Section 138153 of the bill would close a loophole that has allowed some investors, such as cryptocurrency enthusiasts, to generate realized losses on ‘losing’ positions, that can be used to offset other gains, without truly disposing of the position… at least for any meaningful period of time. More specifically, while IRC Section 1091 has long contained the “Wash Sale Rule”, the actual language of the provision used the terminology “shares of stock or securities”.

Notably, many investments are not considered securities, and thus, have allowed owners to escape the Wash Sale Rule. But not anymore. At least not for cryptocurrencies (and other digital assets), commodities, and foreign currencies, all of which would become subject to the Rule beginning in 2022.

Nerd Note:

Given the likelihood that the Wash Sale Rule will apply to digital assets (e.g., cryptocurrencies), foreign currencies, and commodities beginning next year, if individuals currently hold such positions at a loss, now would be a good time to consider selling them, and repurchasing shortly thereafter (maybe a day?) to lock in the loss but continue to hold the investment.

In addition to the new asset types that would be subject to the Rule, the bill would also amend the text of IRC Section 1091 to extend the Rule to purchases of a substantially similar investment made by a “taxpayer (or a related party).” The new “related party” language would trigger the Wash Sale Rule in the event that a substantially similar investment was made not only by the taxpayer, but also by the taxpayer’s spouse or dependent, or an entity controlled by the taxpayer within the Wash Sale window. The bill would also codify that the Wash Sale Rule applies in situations where the substantially similar asset is purchased within a taxpayer's or related individual’s tax-favored account, such as an IRA, MSA, HSA, 529, 401(k), 403(b), or another retirement plan.

The prohibition on after-tax conversions really concerns me, since this will negatively impact a lot of our clients. I have called my Representative to voice my strong opinion against this provision. I hope you will too. https://ziplook.house.gov/htbin/findrep_house

In the chart “Additional Tax Paid on Income Over $400,000”, can you help explain why there is any additional tax for MFJ filers between $400k and $450k of income? Seems they would face the same 32% and 35% tax rates with the same break point in 2021 or 2022.

I don’t see the chart you are referring to. I agree with what you state about the rates.

Jason – thanks so much for catching that glitch! We removed the incorrect graphic and replaced it with an updated version that makes more sense.

Let me understand this. Under one scenario if I make under $400,000 per year I can still do a backdoor ROTH until 2031. Encouraging ROTH conversions for tax revenue. But if like me, retired and deferring SS until I turn 70, I cannot do a ROTH conversion do to the fact I have less than $9000 of after tax contributions in a my total IRA accounts of $1,500,000. Go figure. Need to get rid of the pro rata rule.

Terrific recap of the situation, as always.

To your point … “I may have missed it, but I didn’t see anything on backing out Roth conversion income from the Adjusted Taxable Income Amount. If that is, indeed, the case, then making a Roth conversion could push you over the income limit to make a Roth conversion?”

I wondered the same. If they really are going to do hard caps, then it could be that *if* you went over the AGI limit (i.e., the conversion put you over the top), then perhaps the ENTIRE conversion is now void. The other option is that every dollar is good up to the AGI cap is good. Either way, they better spell it out concisely.

Incredible summary and turnaround. Thank you Jeff. But I don’t see anything

indicating what will happen to the standard deductions. Will these

revert back to the pre-TC&JA targets, or will they be based on the

current targets under the TC&JA?

Nice job Jeff. Thank you. Now get some sleep. You earned it.

If a married couple currently has a combined lifetime exemption of $10M and gifts away $6M this year, making their estate $4M, what happens if the exemption is reduced to $5M in 2022? Have they gifted more than the exemption in the eyes of the IRS, meaning they’ll be taxed? Are they allowed to gift anything above the annual exemption moving forward?

(I understand these aren’t today’s numbers. I’m using easy numbers for the sake of the example.)

if they are gift splitting then each would use $3 million their exemption in 2021. if the exemption decreases to $6 million per person in 2022. they would then have $3 million remaining. in your example, even if they didnt gift split, one spouse would have full use of their exemption amounts. If each only has $5 million of exemption in 2021 (to equal the $10 million combined exemption) and they give away $6 million ($3 million each) then they would have a $6 million exemption – $3 million used and still retain $3 million of exemption. In my experience, it is best for one spouse to fully utilize their exemption.

Hello, can someone comment on their understanding of the after tax $ not being eligible for Roth conversion? I.E. client has a $1mil IRA and $100k of non-Roth after-tax contributions and converts $1 to Roth… is it no longer 90 cents taxable per the pro rata rule?

I had a question on the S-Corp profits 3.8% surtax. How would this work if BOTH spouses were successful S-Corp owners (assuming MAGI >$500k)?

Not sure I understand this example in the Capital Gains section:

—————

Example 1: Darryl is a single taxpayer who, after accounting for all income and deductions, has $470,000 of taxable income for 2021, which consists of $380,000 of ordinary income, $50,000 of long-term capital gains attributable to sales completed prior to September 14, 2021, and $40,000 of long-term capital gains attributable to sales completed on and after September 14, 2021.

When calculating Darryl’s tax liability for the year, his ordinary income will be counted first. Next, his long-term capital gains from prior to September 14, 2021 will be factored in. Thus, he will owe a 15% rate on the first $20,000 of those gains, and a 20% rate on the remaining $30,000 of gain. Finally, all $40,000 of the gain from September 14, 2021 and beyond will be subject to the new 25% top rate.

—————

Why is $20k of the gains getting 15% rate, while $30k getting a 20% rate? The assumptions are weirdly worded too. Is the $470k total income or total taxable income?

ILIT Funding after enactment- This issue seems super easy to avoid, via a more extreme “Crummy” process. Couldn’t the client gift $15k directly to the beneficiary (or more with Federal gift tax filing)? Then the beneficiary may elect to deposit funds into the trust. Doesn’t everyone have the right to deposit into any trust? This may void the creditor protection, as cant protect your own assets, but otherwise preserve the estate treatment of the trust. As beneficiary of the trust, and the prospect of insurance lapsing if they don’t personally fund, clearly have their own beneficial interest in depositing funds. Wouldn’t that work?

What about taxpayers that are already in distribution status? Is the new 50% IRA RMD in addition to their regular RMD amount?

This is the best article I have found yet! Really well done.

The logic in the “Prohibition On After-Tax Conversions” section, re: (Future) prohibition…” is confusing to me.

It states…”Rather, for taxpayers with Adjusted Taxable Income (yes, yet another ‘type’ of income to keep track of) in excess of an applicable threshold, it would prohibit Roth conversions altogether. But not right away…” “…the prohibition on conversions for high-income taxpayers would not take effect until 2032.”

Then the article goes on to define high-income taxpayer thresholds. The implication of the above statements are that those OVER these thresholds are NOT prohibited right away [to encourage conversions]. I.E., you must have more than the income thresholds to make conversions to Roth.

However, the remainder of this section of the article, discusses as if only those UNDER the income thresholds will be able to continue to make ROTH conversions until 2032 and if you are OVER the income thresholds you are prohibited in any year you are over.

This confused me… which side of the income thresholds are able to make conversions until 2032?

Thanks.

Actual Text:

Section 138311. In order to close these so-called “back-door” Roth IRA strategies, the bill eliminates Roth conversions for both IRAs and employer-sponsored plans for single taxpayers (or taxpayers

married filing separately) with taxable income over $400,000, married taxpayers filing jointly

with taxable income over $450,000, and heads of households with taxable income over $425,000

(all indexed for inflation). This provision applies to distributions, transfers, and contributions

made in taxable years beginning after December 31, 2031.”

Reading this actual text, my interpretation is, anyone can still convert pre-tax to Roth [subject to 10m/20m limits] until Dec 31, 2031. After Dec 31, 2031, the income thresholds apply (indexed for inflation) for any pre-tax conversions to Roth.