Executive Summary

While many of today’s workers may ultimately be in the workforce for 40 years or more, several recent studies have revealed that income growth does not occur steadily throughout that working career. Instead, the majority of our raises actually come in our 20s and 30s. By our 40s, income growth slows dramatically, and in our 50s income growth typically turns negative (at least on an inflation-adjusted basis)!

Accordingly, the reality is that for those in their 40s and 50s who are behind on retirement, there really is little to be done aside from working longer, or cutting lifestyle spending. In other words, there’s not much room for raises and future income growth to bridge the gap.

On the other hand, for those in their 20s and 30s, the fact that the biggest raises come early in their career means it’s especially important to control the pace of spending increases in the first place. Otherwise, the steady lifestyle creep towards an increasingly expensive life as our income rises may not only crowd out the ability to save now, but leave little room to save in the future as earnings growth slows. Fortunately, though, the magnitude of earnings increases in our early years means that good spending habits established early on can make an astounding difference over a lifetime!

Early Income Growth Shapes Lifetime Career Earnings

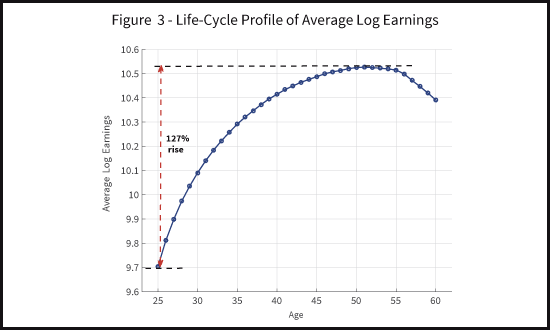

In a recent Federal Reserve Bank of NY study entitled “What Do Data On Millions Of U.S. Workers Reveal About Life-Cycle Earnings Risk?” by Guvenen, Karahan, Ozkan, and Song, researchers evaluated how employment earnings tend to change throughout our working years.

The somewhat surprising result of the study was that the “conventional” financial planning view that earnings rise steadily (above inflation) throughout our careers is not accurate. While overall the study did find that our “peak” earnings are on average 127% higher than where our careers start in our 20s, the career growth is not evenly distributed throughout our working years.

Source: "What Do Data on Millions of U.S. Workers Reveal about Life-Cycle Earnings Risk?" by Guvenen, Karahan, Ozkan & Song

A cumulative career earnings growth of 127% over nearly 30 years from age 25 to age 55 equates to a real growth rate (above inflation) of almost 3%/year, but as the chart makes clear, the growth is disproportionately concentrated most heavily in our early working years, begins to level off mid-career, peaks on average by our early 50s, and then actually declines in the final decade before retirement.

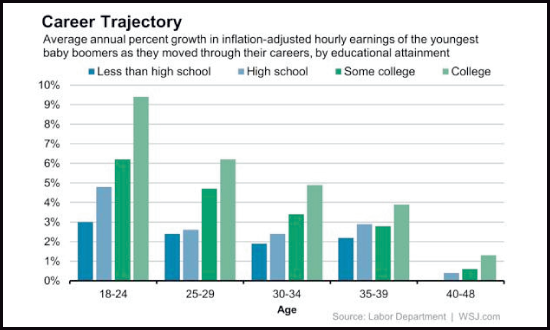

A recent study from the Labor Department also found a similar phenomenon; having tracked a cohort of 10,000 later-stage Baby Boomers from 1979 up through 2012, the research showed that the greatest income increases (over and above inflation) came in their 20s, with slowing income growth in their 30s, and only modest income growth by their 40s.

Source: "The Youngest Baby Boomers Got Their Biggest Raises Early", WSJ & U.S. Labor Department

In other words, the results suggest that a worker’s career and income path have significant potential in the early years – for better or worse, that’s when the bulk of above-inflation raises are generated, as we learn the skills necessary to grow into our careers, get promotions, and set our subsequent career trajectory. But the outcome of that path is largely set by our early 40s, riding it out from there only modest income increases for the next decade, followed by a subsequent decade of decline before retirement.

A Rising Standard Of Living Makes Retirement More Expensive

The fact that the bulk of our spending increases come in our early working years means our spending and savings habits in the early years can have a disproportionately large impact later, as 'problems' created early on can't be erased by rising income later. This pertains not only to savings habits in general, but it’s especially important for those in their 20s and 30s to manage their spending increases as income grows, or it creates a subsequent lifestyle that can't be sustained as income growth levels off.

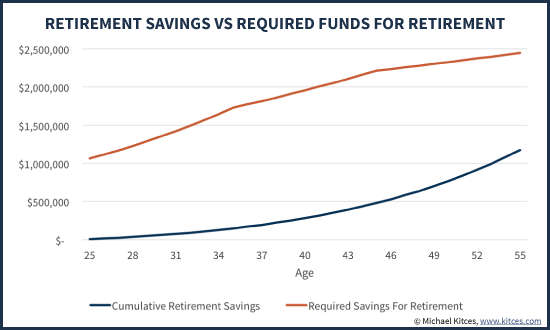

For instance, imagine a situation where you save 15% of your (rising) income, which starts out at $50k/year at age 25, and it grows at 5%/year (real) for the first decade of your career, 2.5%/year for the next decade, and 1%/year in the last decade. The outcome is charted below; the blue line is your cumulative retirement savings (assuming a 7% annual growth rate), and the orange line is how much you would need to sustain your then-current lifestyle in retirement (assuming a 4% withdrawal rate in retirement).

As the results reveal, the problem with these situations where lifestyle spending rises along with your income growth is that, for most of your 20s and 30s, retirement actually gets further away! The rising lifestyle costs necessitate an ever-greater lump sum necessary to sustain that higher standard of living, which then dwarfs even the relatively "good" savings habit of 15%-of-income in the early years. The problem is that "just" saving 15% of your income in your 20s turns out to be far too little given how expensive lifestyle is by your 30s, and likewise saving "just" 15% of income in your 30s turns out to be far too little given the cost of your increased standard of living by your 40s.

In fact, this phenomenon likely explains the “gap” of so many of today’s 50-somethings struggling to retire!? Lifestyle moved with spending increases, and now the only way to bridge the gap is to pray for compounding market growth to save the day!

Combating “Lifestyle Creep” And Managing Spending Raises As Earnings Grow

The real challenge of an increasingly expensive lifestyle is that often such rising costs are more of a "lifestyle creep" effect that occurs gradually, as small changes in lifestyle decisions cumulatively add up over time. It could be getting someone to do the housekeeping or gardening, not realizing that $50-$100/week for services quickly adds up to thousands of dollars per year. Or eating out more often – or at fancier restaurants. Or taking more expensive vacations.

In other situations, the rising costs are more overt. For instance, as income grows, it becomes possible to purchase a more expensive car. Yet the problem is that buying a more expensive car often becomes a lifestyle choice of always buying cars at that price point – once you've driven for years in a luxury car, it’s hard to go backwards to a 'lesser' model. Similarly, once you buy a new car for the first time, it's often difficult to go back and buy used again. Housing creates the same challenge. At higher income levels, we become “qualified” to buy (or rent) a more expensive home… but once we get accustomed to that kind of home/lifestyle, it’s hard to downsize.

Of course, as long as income continues to rise, these increases in lifestyle may not feel problematic. And the changes may be so subtle from year to year that you don’t even realize it’s happening – thus the lifestyle changes just “creep” up on you.

Yet as shown earlier, the cumulative impact is significant, as increases in lifestyle spending not only mean there’s less money left to save, but also that higher lifestyle spending means we need even more to retire in the first place.

Planning Issues For Clients With Uneven Earnings Growth

From the financial and retirement planning perspective, the implications of this (uneven throughout lifetime) earnings growth research is significant.

On the one hand, these results suggest that as planners we should be very cautious about the income growth projections we assume for clients, especially in their later years. Generating much of any income growth over-and-above inflation in our 50s and beyond is clearly not the norm (though notably, the studies do find that income growth in later years is slightly more likely for those at the upper end of the income scale in the first place, which is disproportionately the types of clients that financial planners tend to work with). In turn, this implies that to the extent clients in their 50s have a retirement shortfall, the gap will have to be bridged almost entirely by some combination of working longer (to save for more years and allow growth to compound for more years), and/or by cutting spending – since at ‘best’, income is likely to remain flat (adjusted for inflation), and may even begin to decline.

On the other hand, when it comes to planning for younger clients – those in their 30s, and especially in their 20s – the research makes the point that if anything, we may be under-projecting the potential income growth that clients are likely to generate in the coming decade. The good news is that means young people today who are having trouble saving really do have a greater likelihood of being able to make it up later. And in fact, with the greater upside income potential, arguably it pays even more for young people to be reinvesting into themselves and their careers in order to boost their future earning potential rather than “just” trying to save more in a retirement account.

Yet the fact that the greatest income increases tend to come in a stage of life where we may not yet have as much experience managing money and spending responsibly, and/or are still establishing our spending and lifestyle habits, means that a focus specifically on spending and lifestyle decisions is especially important for those in their 20s and 30s. It’s not necessarily about spending less today, but about making sure that spending does not increase as rapidly in the coming years; in other words, the biggest issue for young people is not necessarily about saving more today, but about making sure you save more tomorrow by saving a larger portion of future raises because this is when the largest raises tend to occur. And it’s a lot harder to avoid spending increases going forward, than it is to increase spending now and have to go backwards on lifestyle later!

Unfortunately, though, most financial planning software today does not have the ability to model “uneven” income increases throughout a client’s working years. Nonetheless, the research does imply that it may be reasonable to assume significant increases in client saving through their 20s and 30s… at least, if the client(s) can keep control of spending as those raises come along.

The bottom line, though, is simply this: for those within a decade or two of retirement, income growth in our later years is not likely to bail us out for our earlier decisions, leaving little choice but to work longer or engage in those uncomfortable spending cuts. Yet for those who are younger and still have a long time horizon in front of them, the reality is that while early savings habits are good, learning to make prudent spending decisions may have the greatest impact of all – especially when it comes to controlling increases in spending as income rises!

So what do you think? Would you plan differently knowing that the bulk of real (inflation-adjusted) income increases come in the early years? Is this consistent with your own experience with clients?

Good article. The emphasis again is on living well below your means. It is hard yo resist the lure of a shiny new car or a big house with pool when you can afford it. But these luxury lifestyle decisions can eat into the security of our retirement or estate planning. Always save more and spend less than you can afford. You do not want to be financially dependent on others when you are old

Your analysis conveniently ignores that the majority of lifestyle spending increases are correlated with getting married and starting a family. Income increases occur, and then people feel financially confident to buy their first home, get married and have a child. The amount of spending increase generated by those milestones dwarfs the spending increases generated by non-essentials. Sure, we spend lots more in our 40’s and 50’s, usually associated with college tuition for our children. With an empty nest, you can downsize your home, and many folks do that. A lot of big spending does have an end in sight, and you don’t account for that, or the fact that we might pay off our homes by the time we hit retirement age.

Good article. I certainly feel the older I get the less income I have to spend, yet I earn more money. If only I knew back in my early twenties that financial planning then could have made me very wealthy today. Something I’m trying to convince my son so he doesn’t make same mistakes.