Executive Summary

As financial advisors, we're well aware that behavioral biases influence our clients' decision making. However, it's sometimes easy to forget that biases influence the consumption of financial planning services as well, which may have an impact on client satisfaction, retention, and our ability to grow and sustain our business.

In this guest post, Derek Tharp – our new Research Associate at Kitces.com, and a Ph.D. candidate in the financial planning program at Kansas State University – explores the "Bottom Dollar Effect" and its varying influence under different financial advisor business models.

The "Bottom Dollar Effect" refers to the tendency of consumers facing financial hardship to transfer negative emotions associated with their hardship onto the last few products or services that, at the margin, they perceive as straining their budget. The unfortunate consequence of this effect is that consumers may become dissatisfied with a purchase based not on their actual satisfaction with the goods or services purchased, but instead, on the timing of that purchase and the resources they happened to have available at that time.

Within the context of financial planning, various business models - from hourly or retainer fees, to charging on assets under management - possess different degrees of potential susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect, driven primarily by the various "mental accounts" that client fees typically come out of. In addition to being highly salient and possessing some other negative behavioral characteristics, hourly fees are particularly prone to the Bottom Dollar Effect, as planning fees tend to be relatively large, irregular, and funded through current income (thus, more likely to strain a client's budget). On the other hand, AUM fees have low susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect, given that fees come out of a long-term mental account tied to a dedicated goal (retirement) that is insulated from current income fluctuations. Retainer fees vary in their susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect based on their design, including especially their size relative to client's income and net worth, and from what account(s) the fees are paid.

The fundamental point, though, is simply to understand that decisions about how to pay advisory fees are subject to behavioral biases as well, and those biases may influence both your ability to succeed as an advisor and your clients' inclination to retain your services (particularly in bear markets, when they may need your help the most!). In order to maximize the chances of establishing a relationship that benefits both you and your clients long-term, behavioral biases – including the Bottom Dollar Effect – should not be ignored!

Financial advisors spend a lot of time thinking about how behavioral biases affect their clients’ decision making. Whether it is investment decisions, risk management, day-to-day budgeting, or any other domain of personal finance – biases play a large role in behavior.

However, one thing advisors may underappreciate is the role that biases play in the consumption of financial planning services themselves. After all, from a client’s perspective, working with a financial advisor is just another form of professional services consumption (and often a fairly expensive one!). If advisors aren’t careful, compensation methods that are poorly designed from a behavioral perspective could result in behavior that is bad for both the advisor and their clients.

What Is The Bottom Dollar Effect?

The “Bottom Dollar Effect” refers to the tendency of consumers facing financial hardship to transfer negative emotions associated with their hardship onto the products or services they perceive are straining their budget.

The phenomenon was first identified in a 2014 study by Soster, Gershoff, and Bearden, where the researchers explored how spending when a consumer’s available resources are depleting negatively influences satisfaction with goods or services purchased. This is particularly true as spending approaches a consumer's last or “bottom dollar”.

Through a series of six different experimental studies, they found evidence that consumers transfer negative emotions associated with their financial hardship onto the products or services that they perceive are straining their budget. In other words, purchasing is more painful when a consumer's budget is relatively low.

Mental accounting plays a key role in the Bottom Dollar Effect. If people were perfectly rational, we would treat all of our resources as fungible. Our consumption decisions wouldn’t be influenced by the order in which we acquire or spend assets. Yet, we know that people actually do categorize their spending behavior. In fact, as advisors, we often encourage it in the form of budgeting – including strategies like placing cash into envelopes earmarked for particular spending categories.

Three Types Of Mental Accounts

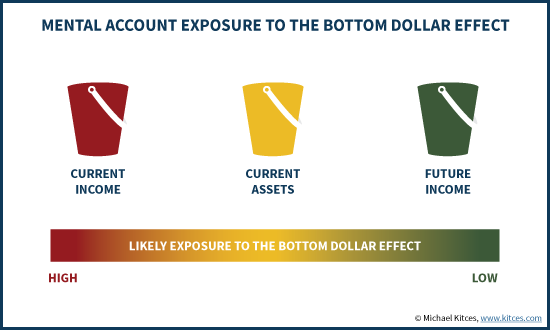

Within Shefrin & Thaler’s mental accounting framework, people are assumed to have three broad mental accounts for resources: current income (e.g., income and cash in a checking account), current assets (e.g., investment accounts associated with shorter-term goals and less liquid assets such as home equity), and future income (e.g., dedicated retirement savings and human capital). The distinction matters, because our tendency to spend (also known as our Marginal Propensity to Consume, or MPC) is higher from some categories (e.g., current income) than others (future income). Because clients facing hardship will typically consume resources out of current income and assets (e.g., spending down an emergency fund, rather than tapping into a retirement account), the Bottom Dollar Effect is primarily an effect associated with shorter-term resources.

Soster et al. looked beyond just questions of mere propensity to consume among various accounts. In particular, they examined how the pain and pleasure associated with consumption is influenced by the level of resources within a mental account. Across six experimental studies, they found evidence that:

- Consumers are more averse to costs incurred as budgets approach exhaustion (i.e., the Bottom Dollar Effect).

- The Bottom Dollar Effect is more pronounced when the effort to earn budget resources is higher.

- The Bottom Dollar effect is reduced when participants know that resource replenishment is imminent.

Another important concept related to client behavior and advisory fees is fee saliency. Fee saliency refers to how cognizant we are of fees paid for services. Prior research has found that consumers perceive value differently based on how salient pricing is. When saliency is high, the costs of goods or services are more readily apparent to us and we tend to be more critical of the value we receive.

The Bottom Dollar Effect Among Different Pricing Models

Because different financial planning fees come from different mental accounting categories, some of which are more susceptible to the Bottom Dollar Effect than others, the Bottom Dollar Effect can play a role in how clients perceive financial planning fees. As a result, the choice of the financial advisor’s pricing model can impact how likely it is that the financial advisor’s fees will be impacted by the Bottom Dollar Effect.

Hourly Fees and Project-Based Financial Planning

Hourly fees and project-based financial planning have become an increasingly popular compensation method among advisors. And while these types of fees do open up the possibility of serving some markets that can’t be reached otherwise, they also possess some poor behavioral characteristics. In particular, they are both highly salient fees (which can increase fee resistance and unwillingness of clients to pay for financial planning), and fees that are typically deducted out of current income, which means they are especially susceptible to the Bottom Dollar Effect.

Few people specifically earmark a portion of their savings in advance for future ad hoc financial planning services. As a result, most hourly or project-based fees are likely funded out of the mental account for current income or assets. Yet, in times of financial hardship, these resources (and the mental accounts associated with them) tend to be exhausted first. And good luck convincing a client that your services are valuable when they perceive your fees as depleting their short-term savings!

The unfortunate insight of the Bottom Dollar Effect is that even if clients would normally be perfectly happy with an advisor's services, upon experiencing financial hardship (which is entirely out of the advisors control!), they may become irrationally dissatisfied with an advisor's services. This may even happen when those services truly are helping the client’s situation!

Hourly and project-based fees also face the challenge of high fee saliency. As anyone who has ever contemplated whether they really need to call an attorney or not can attest, hourly fees are highly salient. We are acutely aware of fees like these and we often try to avoid them.

Further, the nature of hourly and project-based fees is that they tend to be bunched together at a particular point in time rather than spread out as retainers and AUM fees are. Not only does this have an impact on saliency, but this bunching may further increase susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect. While an AUM client is typically billed quarterly and a retainer client may spread out the cost of their annual plan update over the course of a year, an hourly client may receive the total cost in one invoice. Concentrating this cost at one point in time may increase the likelihood that financial planning fees are perceived as depleting a client’s resources.

Assets Under Management (AUM) Fees

Compared to hourly and project-based fees, AUM fees exhibit superior behavioral characteristics.

In particular, AUM fees are typically debited directly out of long-term investment and retirement accounts, which are part of the mental accounts associated with future income. As a result, there is almost no risk that an AUM fee would be subject to the Bottom Dollar Effect. While a client facing financial hardship may be worried about the depletion of their current income and short-term savings accounts, these are not the accounts from which AUM fees are typically deducted. And notably, even if the client actually does need to tap a long-term savings account as a result of their financial hardship, the self-mitigating impact of AUM fees – that the fee declines as the account declines – further helps to reduce its susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect.

AUM accounts also possess superior characteristics regarding fee saliency. While clients may be fully aware of AUM fees (as they must explicitly consent to them in an advisory agreement), and the fees may be fully transparent (supported by notifications when fees are deducted, and a clear line-item in the investment account showing the exact fee deduction), the automatic deduction of AUM fees doesn’t draw extra scrutiny to itself the way an hourly fee does, because the client isn’t explicitly writing a check for every fee.

In addition to the convenience of not needing to make payments themselves each billing period, the ongoing growth of AUM accounts (assuming a client is in an accumulation phase) means that over long periods of time, clients will watch their accounts continue to grow even after fees have been taken out. This unique characteristic of AUM fees may result in a sort of reverse-Bottom Dollar Effect, as the fees not only fail to strain their budget within a mental account, but their resources within the mental account are actually increasing even after paying the respective fees, further increasing the client’s comfort level with their AUM fee.

The combination of deducting fees from a long-term mental account, low fee saliency, and low susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect, give AUM pricing strong behavioral advantages relative to hourly and project-based compensation models.

Annual, Quarterly, Or Monthly Retainer Fees

Relative to both project/hourly fees and AUM fees — each of which have stronger sets of norms associated with their use in the financial planning industry — retainer fees are subject to significantly more variability in their actual use by advisors. And from a behavioral perspective, the characteristics of retainer models also vary.

For instance, some retainer models are deducted directly from retirement accounts (long-term mental accounts), which means they have little susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect, as they are not likely to deplete an account given their size relative to the overall account balance. In addition, the automatic deduction of a retainer from an investment account reduces its saliency, too. The end result: such retainer billing actually retains most of the behavioral advantages of AUM pricing.

However, other types of retainer models — particularly those aimed at reaching markets which can’t be profitably served through an AUM model — may face Bottom Dollar Effects similar to hourly fees, especially if the fee has to be deducted directly from short-term savings or current income. In fact, billing from those accounts may be an inevitable requirement if clients don’t have investment accounts or any other long-term asset pool accumulated yet in the first place, which means it is simply a “necessary evil” from a behavioral perspective.

Fortunately, automating payments to reduce the saliency of a fee and breaking down an annual retainer into a monthly retainer fee can help spread out the cost, but still, clients who don’t have AUM assets to manage and “must” be billed through retainers face the possibility of being subject to the Bottom Dollar Effect.

Why Retainers May Not Actually Be More Stable Than AUM

One of the primary concerns regarding AUM fees is declining revenue during a bear market. Bear markets will inevitably emerge, and when an advisor’s revenue is based on their assets under management, significant declines in asset values will result in a significant hit to an advisor’s revenue. To make matters worse, this decrease in revenue may come at the same time an advisor needs to put in more work to keep clients happy while also facing an increased likelihood of client attrition (though, the flipside of this dynamic is that there is an increased opportunity to acquire new clients from competitors as well!).

Because retainers don't necessarily fluctuate with market value, retainers are thought to be more stable than AUM. However, the Bottom Dollar Effect does give some reason to question this assumption, and particularly among advisors who are utilizing retainers as a way to differentiate from the AUM model. In a bear market, clients may feel like they’re losing out on future income while also facing a reduction in their current income (e.g., layoffs, pay cuts, bonus freeze, etc.). As a result, the Bottom Dollar Effect may still kick in and a retainer fee paid out of current income may be more likely to be cut than a comparable AUM fee! Further, advisors who focus on a particular niche could be particularly prone to shocks among their client base (e.g., a company that goes under or a recession that hits an industry particularly hard), though an advisor's niche may also guard against the Bottom Dollar Effect as clients can more clearly see the unique value provided by their advisor.

Dealing With The Bottom Dollar Effect

Advisors utilizing project, hourly, or retainer models that are susceptible to the Bottom Dollar Effect will want to seek ways to minimize the impact of this bias on their clients to improve client satisfaction and retention.

Of course, consumers should be encouraged to critically evaluate whether any fees they pay to an advisor are justified by the value they receive, but this evaluation should ideally be made in a calm and rational manner. This is particularly true if clients are in the midst of financial hardship and need to make good financial decisions (and may need an advisor to help them do so!).

Adjusting Fees In Response To Income Shocks

One particular concern associated with fees taken out of the mental accounts associated with current income is the possibility that a sudden decrease in a client’s income (e.g., from losing their job) could strain the client’s budget and make them susceptible to the Bottom Dollar Effect. While AUM advisors aren’t exposed to this effect in the first place, those using retainers could adopt a pricing model that naturally adjusts the fee if income declines to guard against this.

Example 1. Some advisors are experimenting with a retainer fee that is calculated based on 1% of income and 0.5% of net worth (which is then paid annually or even broken down into monthly retainer payments). Thus, if a married couple each earns $75,000/year and they have a total net worth of $100,000 (with most of their assets within their short-term savings and employer-sponsored retirement plans), their monthly fee would be roughly $167. If one spouse were to suddenly lose their job, the client’s fee would drop to about $104 per month, and the “automatic” fee reduction may help reduce the client’s incentive to just cut the advisor’s services (and cost) altogether.

Obviously, this has the adverse impact of decreasing the advisor’s income as well (at least in the short term), but temporarily decreasing fees for a client who is retained may be better than losing the client (and their fees) altogether, especially if the payment mechanism will naturally rebound when the client’s financial situation does as well.

Would this reduction be enough to avoid the Bottom Dollar Effect entirely? It’s hard to say. If the couple fully depletes their emergency fund and the spouse remains unemployed for a long time, eventually the advisor’s services may have to be cut from the budget. Still, the automatically adjusted fee should help to soften the impact and reduce the strain on current income. Notably, though, ‘automatic’ fee reductions under a retainer model would also require a process to actually change the fee mid-year, as waiting until an annual renewal (and an annual fee adjustment) might not be soon enough for a distressed client.

Beware Retainer Fees Driven By Net Worth But Paid From Income

In the retainer example above, the advisor was assumed to use a retainer where the majority of the original fee was attributable to the client’s income. This type of structure makes sense when human capital is a client’s largest asset and their resources exist primarily as a stream of current income.

Of course, not every context in which an advisor may be using this type of fee necessary matches the situation above. The same fee schedule could be used with a client who has substantially more net worth than income. Under these circumstances, advisors may want to be even more concerned about income shocks.

Example 2. Assume the same retainer fee as above (1% of income and 0.5% net worth), but this time, it’s for a single client with $100,000 in income and $1,000,000 in net worth. This client’s monthly retainer fee would be $500. Assuming again that the only option for paying the fee is out of current income or short-term assets (e.g., the bulk of their investible assets are within employer-sponsored retirement plans), a significantly higher proportion of this client’s cash flow would be going towards paying financial planning fees. Additionally, if the client were to face a shock in their income, even if the fee were to immediately adjust, roughly $417/month would still be owed just based on their net worth alone. Yet, paying roughly $5,000/year from current income for financial planning fees (even if it’s “reasonable” based on net worth) would present the risk of stressing the household’s income accounts and inducing the Bottom Dollar Effect.

Of course, it’s also possible this shock would trigger a rollover of the employer-sponsored retirement account, and if the financial planning retainer fee could subsequently be paid from there, it might actually improve the situation (from the behavioral perspective). But there’s certainly a risk for a shock to occur without necessarily freeing up manageable resources (e.g., demotion, job loss of a high-income spouse with little employer-sponsored assets, net worth tied up in real estate or other assets, etc.).

A Financial Planning Fee Holiday?

For advisors who want to aggressively mitigate the Bottom Dollar Effect, they could consider a “fee holiday” or some other means of temporarily reducing or waiving a client’s fee during times of financial distress.

Though not specifically targeted towards mitigating the Bottom Dollar Effect, both Schwab and TD Ameritrade have offered fee rebates to their clients in managed accounts since 2014. Schwab’s Accountability Guarantee offers clients a refund of one quarterly fee if they’re unhappy for any reason, while TD Ameritrade’s Amerivest Fee Rebate (which ended in October of 2016) offered eligible clients a refund of two quarters' worth of fees if their account doesn’t grow (excluding fees) over those two quarters.

Notably, both Schwab and TD Ameritrade’s programs typically offer rebates on mental accounts that would be associated with longer-term assets in the first place, and for this reason, their rebates may not do much to mitigate the Bottom Dollar Effect. But for advisors that bill from current income, a fee holiday may be beneficial for mitigating the Bottom Dollar Effect during financial hardship.

Adjusting The Timing Of Advisory Fee Deductions

Another interesting finding from Soster et al. is that even when a client is in a state of stress, the timing of costs still matters. All else being equal, the closer an account was to depletion, the stronger the Bottom Dollar Effect. In other words, a $200 expense when a client has a mental account balance of $1,500 will be perceived less negatively than a $200 expense when their mental account balance is $300 (even if both expenses were incurred within close proximity to each other).

The practical takeaway here is that the best time to bill a client is the same time they get paid. Similarly, the best frequency to bill a client may be the frequency in which the client is paid (e.g., a monthly retainer fee for a client paid monthly and a bi-weekly fee for a client paid bi-weekly), as it ensures a bunched up fee won’t dwarf the value of the short-term account paying it. Even better yet, saliency is reduced further when clients are billed in a manner that they never have to acknowledge the income as part of their short-term mental accounts in the first place (e.g., autopayment with an ACH).

This suggestion may sound excessively self-interested, but the idea here isn’t that advisors should do anything deceptive or that would otherwise reduce the transparency of their fees. Similar to the way that many people, for self-control purposes, have taxes, health insurance premiums, savings, and other important expenditures deducted straight out of their paycheck before they ever credit the money into any particular mental account, it may make sense to treat the payment of financial planning services that same way. In fact, as prepaid legal and financial planning services become more popular employee benefits, we are seeing this same self-control mechanism emerging through employee benefit plans as well (e.g., companies like LearnVest and Financial Finesse offering workplace financial wellness programs). Just as “paying yourself first” (before you ever see the money go into your bank account) can be an effective savings strategy, automating important expenses can also serve as an effective self-control mechanism, and may even have the added benefit of reducing susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect.

The Bottom Dollar Effect With Asset Replenishment

Another insight regarding timing from Soster et al. is that the Bottom Dollar Effect is reduced when individuals anticipate a replenishment of their mental account (or if the account depletion is viewed as “temporary” in the first place). While the Bottom Dollar Effect still exists even if someone expects their account to bounce back, it is reduced under those expectations.

The practical insight for advisors from this replenishment effect is simply to add a bit of nuance to concerns about the Bottom Dollar Effect. For instance, if clients have a good-sized emergency fund to absorb expenses (including advisory fees), it may help tide clients over until they can get a new job and replenish their emergency fund. So long as clients perceive their account depletion as a short-term occurrence that will resolve with time, they may be less susceptible to the Bottom Dollar Effect.

Adjusting The Location Of Advisory Fee Deductions

Notably, since the biggest driver of the Bottom Dollar Effect is when expenses are drawn from short-term mental accounts, one of the best ways to reduce exposure to this behavioral bias is simply trying to bill from long-term mental accounts whenever possible.

As is the case for AUM accounts, deducting a retainer fee from a long-term account eliminates most of the concern related to the Bottom Dollar Effect. Of course, advisors need to be cognizant of the fact that IRA assets used to pay personal financial planning expenses of an IRA owner would be deemed a distribution (and possibly a prohibited transaction triggering distribution of the entire account). Additionally, any fees debited from a qualified retirement account cannot include investment management expenses associated with another account (e.g., debiting expenses associated with a 401k account from an IRA), but assuming that a fee can be compliantly deducted from a long-term investment account, both saliency and susceptibility to the Bottom Dollar Effect will tend to be better from a behavioral standpoint.

Acknowledging that some clients simply don’t have the asset base needed to bill from a long-term mental account, one solution may be to utilize a retainer “on-ramp”. Advisors can use a retainer fee as an “on-ramp” for clients who don’t fit a more traditional AUM model, but then “graduate” them to the AUM model when they do. For instance, an advisor could charge a 1% AUM fee or a $250/month retainer fee for clients with less than $300,000 in AUM. Effectively, this is the same as a typical AUM fee with a $3,000 annual minimum, but by making the transition from a retainer to an AUM fee automatic, advisors can leverage the advantages of both models.

Ultimately, one of the most beneficial services an advisor can provide to their clients is to help them avoid behavioral mistakes. While many advisors do this already, it’s important to remember that an advisor’s services are also part of a client’s overall consumption, and, as a result, are also subject to behavioral biases. Acknowledging the ways that an advisor’s fee schedule may influence client behavior can help advisors both grow their business and improve client well-being.

So what do you think? Have you ever had clients influenced by the Bottom Dollar Effect? Do you think it is a risk worth addressing? Could using both retainer fees and AUM be superior to either on its own? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Really nice to have Derek Tharp on your team, Michael. And good content. But I am trying to get past my own bias that Derek’s picture looks similar to Howdy Doody … https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/ffb93b3115cbcc450bd51cefb4a319aa98480c7c08b7abbaab3e915881401de4.jpg .

Welcome to the community, Derek!

Do most advisors include their investment fees in the financial plan as an expense or goal? I use Money Guide Pro and I don’t know of a way to have returns automatically “reduced” by 1% (or the actual AUM %). A recent client asked me to include it as a goal to fund.

Modify the “Total Return Adjustment” on the What If Worksheet page and reduce the return by your fee.

John,

The most straightforward way to do this is simply to reduce the projected return assumption(s) by the amount of the AUM fee on a forward basis.

So if you were going to project 7% for a balanced portfolio but charge 1%, you’d project at 6%. (Insert your own numbers/assumptions as appropriate.)

– Michael

Thanks, everyone!

For eMoney users, there is an area to show advisory fees (either flat or declining), and then a question on what percentage is eligible for tax deduction. eMoney is cash flow based, and tax sensitive.

On MGP, there is also a line item in the “What If” scenarios where you can add additional “decreases” to returns.

So you have the line that shows the projected return, and underneath it, there should be a box where you could enter the exact, gross fee they pay and then it adjusts the net return %.

I’m surprised the fee deduction is not a default event in MoneyGuidePro, given the ubiquity of the software and the inevitability of investment costs. As you can imagine, omitting this required data significantly overstates the probability of success for most investors.

In addition to the helpful comments herein, I’d add that a financial planner should also ensure they always include a budget for underlying expenses as well. Anything that reduces the expected compound return should be included, given the returns are gross of expense assumptions.

Such a reduction for investing costs should include advisory/planning fees, fund expense ratios, trading costs, bid/ask spreads and market impact costs. There are excellent studies that seek to quantify these, but to simplify: assumptions should be always equal to or greater than the sum of expected advisor fees and underlying investment costs.

Interesting report – kudos to Derek for the research.

It seems to come down in support of AUM fees as a default model in order to preserve the ongoing fee as the client’s mental accounting system will be more forgiving and view, say a 1% of AUM fee as a small number.

The challenge to the industry is, not to use behavioral biases to defend a particular fee model, but to provide a service proposition so powerful and compelling that the client couldn’t live without it – regardless of the preferred fee structure.

Charging AUM, flat retainers or hourly rates will all come under pressure if the value proposition is predicated on fund picking and rebalancing. A comprehensive lifestyle financial planning proposition which thoughtfully answers all the key questions and concerns held by many families is likely to prove more robust and minimise defectors.

For more thoughts see http://www.capital.co.uk/fairfees

Alan,

Fee dynamics are an interesting double-edged sword to me.

The consumerist in me is very concerned about the dominance of AUM fees, precisely because the lower saliency makes clients less cognizant of what they’re paying, and therefore less likely to scrutinize and demand value from the advisor.

But for a financial advisor who DOES provide full value for their fees, the challenge remains that two firms that provide identically-awesome services will have different success as businesses depending on their fee structure. If you’re already providing great service, it’s still natural to want to align the payment mechanism in a manner that is most comfortable for clients.

I don’t know if there’s a magic way to balance that dynamic. Good advisors should be able to structure fees in a mentally convenient way for clients. Bad advisors have the potential to abuse it. :/

– Michael

Derek & Michael,

Thanks for the research, Derek. Very interesting read.

The implications here seem to be mostly about retention of clients. Clients will be resistant to continue with services when they resent or feel the fee is causing budget constraints. I would be interested to know if there is any research on retention rates of AUM firms versus Retainer? My experience is you can see the same or higher client satisfaction when your fees are more transparent to the client, but that is anecdotal.

I also wonder about future implications to the profession. 1% AUM may be industry norm right now, but if you assume the industry will continue to innovate, innovation will likely lead to firms competing by either competing on price of value provided. In either case, firms with high saliency fees may be more acutely aware of their value proposition because they have to articulate it to their clients. I might think this would force them to be more innovative in improving and communicating value propositions in the future.

Jake,

Yes, this is primarily about client retention, not necessarily getting new clients (although there are fee-saliency issues there as well). The Bottom Dollar Effect is primarily about “when something [bad] happens, what do I cut first?” And the first of financial planning fees to be on the chopping block.

In terms of current/ongoing retention rates, unfortunately I’m not aware of any good industry-wide benchmarking data to objectively evaluate this, in terms of what actual results have been in recent years. There’s a lot of data on AUM retention rates, but virtually nothing in the retainer context, one way or the other. :/

– Michael