Executive Summary

In the early years of the financial planning profession, advisors were able to effectively differentiate the brand of their advisory firms by relying on language such as “trustworthy”, “knowledgeable”, and even “fiduciary”, to distinguish themselves from often-poorly-trained broker-dealer and insurance company salespeople. But with the rapidly growing number of CFP professionals who provide fiduciary best-interests advice for their clients, built on their years of experience in providing customized financial planning advice, these terms no longer differentiate a financial advisor, and instead simply describe ‘table stakes’ – bare minimum requirements that any financial advisor is expected to possess. Which raises the question of how, with more and more financial advisors joining the industry or continuing to pivot away from products and into fiduciary advice, do talented advisors cope with this rising ‘crisis of differentiation’ and actually brand themselves in a way that stands apart from the rest?

In this guest post, Amy Parvaneh, Founder and CEO of Select Advisors Institute, explains the process she uses to help advisors develop an effective brand for their firm by identifying the valuable, qualitative factors that make an advisor (or their practice) unique, and targeting the right (not already overly saturated) client segment. By delving into these two key branding strategy elements, a financial advisor can create a strong, relevant message that can promote an individual (or their firm) and elicit client engagement from the exact type of clientele they’ve chosen to serve.

The first of these key branding elements is the firm’s "Opposing Category", which consists of the firm’s qualities that go beyond the mere ‘table stakes’ that all advisory firms must have, and distinguishes the advisor as unequivocally unique from others, such as a unique financial planning process that the firm uses or a specific field of expertise the advisor has.

The second key branding element is the firm's "White Space", which includes any client segments that are underserved by other competing advisory firms, which, by definition, means there would be little competition to serve such clients (and ideally, will include clients with whom the advisor would enjoy working in the first place!).

While Opposing Categories can be identified by an introspective assessment of services offered and qualities that an advisor feels are special, White Spaces are best determined by examining current client characteristics, such as demographic criteria and less frequently examined psychographic traits (which describe a client’s habits, beliefs attitudes, and values), to spot where the advisor may have already found some White Space that can be delved into further. Once the Opposing Categories and White Spaces are identified, the advisor can then create an appropriate, personal, and impactful brand, and then use the brand to synchronize the business image, marketing messages, and operations processes.

Ultimately, going through the process of developing a brand message is crucial for advisors who want to hone their existing client segment (or shift their focus to a different segment altogether). By investing the time and effort needed to develop a relevant, genuine branding message, financial advisors will find their marketing efforts are more effective, as they highlight their specific value proposition to a specific (White Space) clientele to grow a successful practice in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

The Importance of Branding

Vincent van Gogh is one of the world’s most treasured artists, and his most expensive painting, Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890), sold for $82.5 million in 1990. But despite his passion for his work and immeasurable talent, Van Gogh was an obscure artist throughout his lifetime, unable to establish any meaningful following. He sold only one painting before he died, The Red Vineyard (1888), which sold for 400 francs in 1890 (less than $2,400 USD today!). The letters between the artist and his brother, Theo van Gogh, tell of a chronic lack of money, and existential difficulties with which Vincent struggled during his short career.

Similar to Vincent van Gogh, many advisors in the wealth management industry are also faced with an existential dilemma of sorts: One of intelligent, talented, and dedicated financial experts whose value may be overlooked and underappreciated, simply because they are not effectively marketing their specific value proposition. Many financial advisors who are brilliant in their field have never fully understood or implemented a successful marketing campaign, some don’t feel they need one, and some simply never even realized that there are marketing strategies they can actively follow to promote themselves.

For many decades, financial advisors have marketed themselves with bland and undifferentiated messaging that does little to compel their audiences. How often have we seen or heard advisors use phrases to describe their value proposition, such as the ones below?

We are trusted advisors

We help you reach financial independence

We can be your quarterback for all your financial decisions

We provide comprehensive wealth management

In the past, when financial advisors were much more scarce, phrases such as these worked adequately for an advisors’ marketing strategy, because they really did differentiate advisors from the rest who were predominantly product salespeople. However, the ongoing commoditization of investment products and asset allocation is forcing more and more advisors to deliver this same trusted, holistic advice solution, with the number of CFP certificants increasing from 36,000 in 2000 to over 85,000 as of September 2019.

And given the tremendous growth of the comprehensive financial planning industry over the last two decades, advisors have needed to invest more and more energy and creativity into their marketing efforts to distinguish themselves from the competition. Just searching for “Financial Advisor” titles on LinkedIn results in over 550,000 results! Combine that with “Wealth Manager”, “Wealth Advisor”, and “Financial Planner”, and we’re up to about 815,000 and counting! Read about their services on their website or LinkedIn profile, and you can’t see much of a difference in what each does.

At the same time, “fee compression” is the topic du jour among advisors who fear their fees are perceived as untenably higher than the industry average by prospective clients. With the advent of robo-advisors and their saturation of digital wealth management platforms (as well as the focus on passive and index investing), it has become even more difficult to justify a 1% asset management fee, regardless of all the other ancillary services an advisor may offer to clients (or at a minimum, requiring so much in ancillary value-added services that it undermines the firm’s profitability).

Furthermore, given an ever-decreasing attention span in our society with the ubiquity of social media and digital lifestyles, prospects aren’t usually willing to listen to or read long-winded explanations and most blogs on advisor websites. Thus, antiquated marketing material with essays about the benefits of a particular wealth manager do not often compel prospective investors to engage.

And thus, perhaps a bit like Vincent van Gogh, these advisors are not able to effectively express to the outside world the unique qualities that make them different and worth engaging. Perhaps it’s the extra mile they will go for clients (the funerals they are arranging for their clients’ loved ones, the shoulder they offer to a client going through a divorce, the assisted-living facilities they are researching for their clients who are showing advanced symptoms of dementia, the family governance meetings they’ve arranged, and so on), or maybe it’s the specific service they offer to a target niche that make them unique from the rest.

The process of translating the valuable, qualitative factors that make an advisor (or their practice) unique, into impactful messaging that genuinely promotes an individual (or their firm) and that elicits client engagement, is called “branding”.

Historically, the term “branding” was generally reserved for consumer goods and technology companies. Companies like Apple and Nike used branding to build consumer loyalty and recognition – think of the line “Just Do It”, and Nike’s concept of empowering one’s inner athlete immediately comes to mind, right in line with their mission to “bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world.” Or Apple’s award-winning “Think Different” campaign, which reminded customers of their mission to create innovative products based on seeing the world a little differently, with a poignant toast “to the crazy ones,” and the goal to inspire their customers to “think differently” in their own lives.

So how can advisors brand themselves to highlight their unique value, and move themselves away from being a commodity that trades on price, and into a brand, which trades on perceived value and selling of the intangible?

Defining The Branding Message

Pretty websites and marketing materials don’t sell things. Words sell things. And if we haven’t clarified our message, our clients won’t listen.

– From “Building a Story Brand: Clarify Your Message So Customers will Listen”

by Donald Miller

Now that we’ve emphasized the importance of branding and how it should be used to deliver your messaging concisely and with impact, let’s discuss how it can be developed for an advisor (or their firm) to completely differentiate their value proposition from that of other competitors.

Focusing The Brand Message And Targeting The (Right) Client Segment

The most important element of any branding exercise is one word: Focus. Focus on what we want to provide, and focus on who we want to serve.

Defining focus can cause anxiety for some advisors, who try to service clients with a broad range of needs. The issue these advisors face is that, because they are willing to work with any client, they may find it difficult to focus on what specifically they want to (or can) offer. And trying to be all things to all people ultimately ends out as being very little to very few.

In a 2013 Harvard Business Review Case Study, Angela Ahrendts, the former CEO of Burberry, the iconic luxury clothing brand, discussed how she helped a 156-year-old company, growing at 2% in 2006 when she took over, turn into the global powerhouse it is today (revenue grew from £743 million in 2006, to £2.33 billion when she left in 2014, an annualized growth rate of over 15%/year):

The company had an excellent foundation, but it had lost its focus in the process of global expansion. We had 23 licensees around the world, each doing something different. We were selling products such as dog cover-ups and leashes. One of our highest-profile stores, on Bond Street in London, had a whole section of kilts. There’s nothing wrong with any of those products individually, but together they added up to just a lot of stuff—something for everybody, but not much of it exclusive or compelling.

In luxury, ubiquity will kill you—it means you’re not really luxury anymore. And we were becoming ubiquitous. Burberry needed to be more than a beloved old British company. It had to develop into a great global luxury brand while competing against much larger rivals.

Angela Ahrendts defined the Burberry trench coat as a focal point of the company’s identity and representative of the brand’s British culture, and capitalized on the company’s historical core by innovating around the iconic trench coat:

Burberry is 156 years old; its coats were worn in the trenches of World War I by British soldiers, and for decades thereafter they were so much a part of British culture that the company earned a royal warrant, making it an official supplier to the royal family… We would reinforce our heritage, our Britishness, by emphasizing and growing our core luxury products, innovating them and keeping them at the heart of everything we did.

Finding Focus – Opposing Categories and White Space

A firm that is looking to rebrand (or to establish a brand for the first time to begin with) should ask the following two focus questions:

- What is our personal, unique, value-add service offering?

- Who exactly makes up the target market we are going after, particularly those who are underserved by other advisors in our sector?

What Is The Unique Value-Add Offering (Opposing Categories)?

Many advisory firms use words such as “knowledgeable”, “client-centric”, “fiduciary”, “trusted”, and “one stop” to describe their value proposition. While there is absolutely nothing wrong with these adjectives (they are very admirable qualities to bring forth to your clients!), the issue, with respect to branding, is that these terms are overused and do very little to differentiate what you offer from any other advisor. Who wouldn’t expect their advisor to be knowledgeable, trusted, and client-centric?

Messages that identify attributes representing the bare-bones requirements to actually be in the industry, are referred to as “Category Benefits” or “Category Table Stakes”. They are important traits that apply to every company’s brand in the relevant category (e.g., for all financial advisors). And while category benefits are important, they do nothing to differentiate an advisor’s brand – they simply put the advisor in the game. A wealth management team that brands itself as providers of “trustworthy, knowledgeable advice” is simply touting a category benefit that any wealth management team worth engaging would be expected to have.

So instead of using category benefits in brand messaging, the advisor’s goal should be to identify and highlight what unequivocally and objectively makes them unique from other advisors, or what is referred to as an “Opposing Category”. For example, if your firm focuses specifically on individual stock selection in a market segment where most other competitors employ passive investment strategies, you can say that individual stock selection is your Opposing Category. Another example of a firm’s Opposing Category is specializing in education funding and student loan debt management for younger clients, when other advisors in the firm’s prevalent market segment focus on retirement planning for older clients.

Here’s a good test to determine if a brand position you develop will be effective. Decide whether the brand incorporates a valid Opposing Category in your market by asking what someone else would create as an Opposing Category to yours. If you can’t find a reasonable Opposing Category to reflect how you’re differentiating yourself, then the message might just be relying on a category benefit versus an Opposing Category. For example, if your brand position emphasizes building relationships, this would suggest that market segment competitors would mainly be ‘anti-relationship advisors’, and no firm is going to claim that as their Opposing Category!

On the other hand, if a firm focuses on working with military families, in a market where most other firms target clients primarily employed in the private sector, they definitely have a valid Opposing Category.

Who Makes Up the Advisor’s Underrepresented Target Market (White Space)?

Sometimes, the issue with getting very specific gets even more problematic for advisors when we ask them to pick who they want to focus on. The question, “What is your firm’s minimum AUM?” can cause discomfort for advisors who are eager to serve all clients, and who are concerned that establishing a minimum AUM may ostracize existing or prospective clients who don’t meet the new criteria. And ideally, a good focus should be even more narrow and specific than just “clients who have at least $XXX of investable assets”.

When speaking about her approach for targeting the proper market segment, Ahrendts wrote:

“We began to shift our marketing efforts from targeting everyone, everywhere, to focusing on the luxury customers of the future: millennials. We believed that these customers were being ignored by our competitors. This was our white space.”

So the second area of focus in creating brand messaging is to look at potential areas of “White Space”: client segments that are not being adequately served by an advisor’s competitors (and that, ideally, are clients with whom the advisor would enjoy working) .

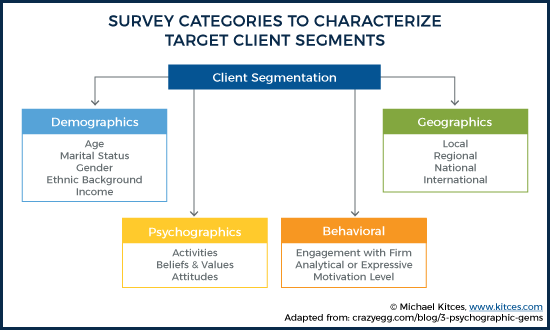

When identifying White Space, demographics (e.g., gender, age, net worth, occupation, etc.) are not the only areas to examine – there are more nuanced aspects about the client segment that should also be considered (and that competitors may be ignoring).

For example, an advisor can assess the interests, habits, attitudes, emotions, and preferences of their current clients or centers of influence (COIs), and decide how important it would be to have similar (or different) personality-based characteristics for the advisor to work well (and happily) with a target client segment. These qualitative traits, relating to a client’s values, attitudes, and activities, are referred to as “psychographics”, and offer a useful perspective for advisors to explore the specific characteristics about their clients or COIs that brought them together in the first place, and that effectively serve to sustain the relationships on an ongoing basis.

As an example, a financial advisor who lives in a community where lake fishing is a very popular sport, and whose specialization is working with clients in the professional fishing and hunting industry, has a very clearly-defined and relevant White Space. By contrast, while ‘baby boomers’ (with the ubiquity of retirement) are arguably no longer an effective retiree White Space, FIRE retirees (individuals retiring extremely early in their careers), or retirees living in cold climates and looking to be “snowbirds” in particular southern (warm!) locales where a financial advisor’s firm is located, could be a vey effective retiree White Space.

Developing Client Surveys To Find The White Space Represented By Your Existing Clients

In addition to psychographics and demographics, advisors can look to their existing client base to help establish the right White Space opportunities.

A best practice to follow is to organize the specific criteria to be assessed (e.g., demographic, geographic, psychographic, or behavioral), and then to gather data (e.g., age, gender, income, residence, hobbies, values, or preferences around how the client prefers to engage with the firm), either through conducting client surveys or hiring a professional to interview these individuals, to identify trends or clusters of existing clients that the advisor might want to pursue further.

Notably, while many surveys are designed to collect demographic, geographic, and behavioral data about its subjects, they often completely miss the boat on gathering important psychographic data. Because while it’s obvious to ask for a client’s age, address, and income level (and behavioral traits can generally be assessed by simply interacting with the client), it may not feel as ‘natural’ to probe a client about their values, attitudes, and activities.

So what can the advisor ask to ensure valuable psychographic details are collected by their client surveys? For our client surveys, we typically focus on five basic concepts that drive most consumer decisions:

- Survive and thrive

- Be accepted

- Find love (either with their family members, at work, with friends)

- Achieve an aspirational identity

- Bond with a tribe that will defend them physically and socially

Survey questions that explore these areas can be very effective ways to collect psychographic information about an advisor’s target client segment. Some sample questions include:

- On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is most important, how important is it for your wealth management platform to offer a sense of community?

- Answers to this question might help determine if clients would prefer a platform that offers socializing and a sense of belonging, or if they would prefer a more discreet, reserved platform.

- What are three words that describe your personality when it comes to your finances?

- These words can give insight into the different drivers behind the client’s decision-making, and can help define how you describe the psychographics of your target client segment.

Essentially, by comprehensively surveying existing clients, the advisor can begin to see those combinations and groupings that might represent a suitable target clientele White Space they may already have, while also better understanding the brand messaging that would be most impactful for their clients.

And once the Opposing Categories and target White Spaces are identified, the advisor can use these elements to craft an appropriate, personal, and impactful branding message. It is crucial for the advisor to stick to the principles supporting the brand, even if it means turning away clients outside of the White Space, and/or who may not benefit from the Opposing Category. Otherwise, the messaging will lose credibility and impact.

Case Study – Turning a Routine Process Into a Proprietary Trademark

Recently, we were engaged by a $3B RIA that wanted to rebrand their image, to identify their true Opposing Categories beyond their knowledge, expertise, and caring culture (the category requirements they had traditionally emphasized in their branding).

We interviewed the team and whiteboarded a lot of ideas, researched the competitive landscape, and reviewed all of their existing content and marketing material. With that as our background, we interviewed several of their clients and centers of influence that the firm had worked with over the years.

We realized that most of the clients who joined them from a competing firm were multi-generational family business owners (the same as the wealth management firm’s own structure), and designated their White Space as the next-generation leaders of long-standing family businesses.

By looking past the language and feedback from the wide range of survey respondents that weren’t really relevant to what the advisors were trying to be for their clients (e.g., some clients mentioned liking the returns they were getting from their managers, and some said they appreciated the firm as their “broker”), and by focusing in on the comments that actually did fit the firm’s White Space, some important ideas and recurring themes that are deeply relevant and unique to the advisor were revealed.

The surveys of the RIA clients and centers of influence identified that the number one distinguishing factor about the firm (i.e., their Opposing Category) was the consistent and unique discovery process they used to relieve clients from the stress and anxiety caused by their finances.

We identified the ten separate steps that made up their discovery process, and which represented their unique Opposing Category, and gave each step a distinct name, incorporating language and messaging that reflected the psychometric data we gathered from surveying clients and COIs. We then used those steps to create an acronym, which were trademarked as the firm’s proprietary process. The firm can now market themselves with this acronym to represent the specific process that truly sets them apart from other firms, reaching the White Space of the particular (next generation leaders of long-standing family businesses) target clientele they’re aiming to focus on.

Implementing The Brand Message In Marketing Material

Once an advisor is clear about the brand messaging that addresses appropriate Opposing Categories and White Spaces, how do they bring it to life through a well thought-out marketing plan?

The key to this step is synchronization: everything must be in alignment with the messaging theme.

For example, if an advisor boils their brand down to focus on a clear and simple investment process, but their firm website is busy and congested with information all over the map, the lack of synchronization will be confusing to the client and will only serve to dilute the value of the brand’s objective. A simple, clean website that allows clients to very quickly understand the process would be a much more synchronized strategy, effectively supporting the intention of the firm’s brand message.

We recently worked with a new firm that had come from a large wirehouse, leaving the wirehouse to go independent. Right before their departure, they were managing close to $2 billion with an average client net worth of around $20 million. The previous firm’s office was right around the block, with their prominently displayed name, visible from miles away, at the very top of high rise office towers.

The team was having a very difficult time explaining the benefits of the new firm to former clients, who were resistant to switching from the large wirehouse. We had been engaged to help the firm with their new branding efforts, and to help them show clients the unique value they offered now that they were practicing in their own RIA.

To get a better understanding of their uphill battle, we visited the client in their new office space. The minute we reached the lobby, we immediately identified a major issue and potential cause for the lack of clients following them from their old firm. The new team’s rented office was a run-down, old-fashioned, shared office space alongside several other (unrelated) businesses, and the RIA’s name was nowhere to be seen upon entering the office.

This posed a problem for the new RIA, because one of the reasons many high-net-worth clients are loyal to large firms with household names is the sense of security and aspiration they experience from engaging with these firms. Which is what the wirehouse offered to its clients – from the large signs on their giant office tower, to the marble floors of the welcoming reception lobby, the aesthetics alone created a feeling of exclusive community for their clients, providing them with the sense that “I’ve made it and I belong here.”

But the new RIA’s office space offered none of this. The target clients were accustomed to the luxurious and safe feeling offered by the prior firm. The downsized, generic, shared space of the new firm was completely unsynchronized with messaging intended for ultra-high net worth clients, and thus only served to ostracize their target market.

So what did the firm do to fix the situation? Given that their new messaging and value proposition focused on an ultra-high-net-worth client segment with estate planning services that weren’t available from the old wirehouse, we suggested a unique partnership with a ‘white glove’ law firm in the same vicinity. The partnering law firm offered their conference rooms and offices to share with the new RIA firm, and provided a complimentary one-hour consultation session with an estate attorney. This allowed the new firm to maintain its current low-rent lease for space where they could run day-to-day operations, and to use the law office facilities to offer clients a posh meeting experience consistent with their brand messaging.

While branding can be a very complex process, it is a crucial element for the future success of your practice.

Once an advisor defines the unique value proposition that is their Opposing Category, and identifies the White Space client segment that they want to target, the ultimate (and ongoing) goal is to make sure all of their marketing materials, client-facing office environment, furniture, website, and even the dress code are completely in line with their brand. Otherwise, the message will be unclear, confusing, and will eventually lose impact and value.

Like the new RIA firm, partnering with the established law firm helped them to align the physical setting experienced by their clients with their target-client’s affinity for luxury and security. Had they invited their clients for meetings in the smaller, rented office space shared with other unrelated businesses, their messaging would have come across unclear, clashing with the values and expectations of their intended target clients.

Accordingly, advisors should revisit their branding message periodically over time, to make sure it is always consistent with their specific value-add qualities and targeted client segment, as these things can, and will, change. As the saying goes, “What got us here won’t take us there”, and advisors who do not continually update their branding to stay current and aligned with their own services and target client run the risk of compromising their brand efficacy.

Like Vincent van Gogh, advisors who aren’t able to cultivate a suitable client base are unlikely to find success, regardless of the amount of vision and talent they may have.