Executive Summary

Given the market volatility of the past 15 years, with both the “tech wreck” and the financial crisis, a growing number of consumers are seeking more safety for their investment portfolios, through everything from more proactive risk management strategies, to using products like equity-indexed annuities and structured notes that explicitly provide for "some" upside participation in bull markets, but with downside protection in a bear market.

Yet the reality is that constructing downside protection and a principal guarantee over time doesn’t actually require products like equity-indexed annuities and structured notes. They can actually be constructed with relatively simple combinations of bonds and either stocks or equity index options. In fact, just buying a portfolio of bonds and using the interest to buy at-the-money call options is sufficient to produce a partial upside participation rate in equities with a downside guarantee!

Unfortunately, though, creating such pairings can be especially difficult in low interest rate environments, as there simply isn’t enough yield to afford very many options contracts, which in turn results in relatively low equity participation rates. Yet given that annuity companies and structured note providers are subject to the same constraints, in the end investors will likely suffer from low returns in such solutions, regardless of which vehicle is used… and in fact may have the greatest upside potential by simply constructing the strategies themselves, and avoiding the internal costs of such products in the first place!

Structured Note Alternatives - Building A 10-Year Downside Guarantee For Stocks Using Government Bonds

Imagine for a moment that you wanted to invest in equities for the next 10 years, but have a guarantee that there would be no downside risk; no matter what, you want to be assured that the portfolio will return at least your principal at the end of the decade.

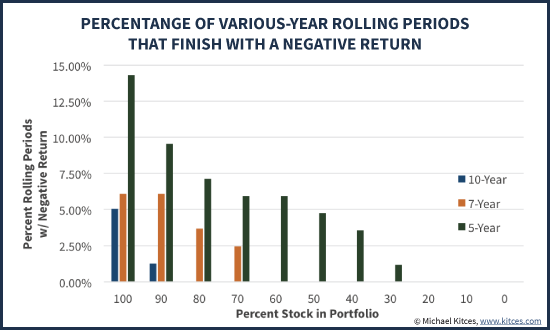

On the one hand, an investor could simply approach this by recognizing that the probability of having a (nominal) loss in equities over a decade is already a very low probability event, and one whose probability declines even further by diversifying into bonds. The chart below shows the probability of having a cumulative total return that is negative after rolling 5-, 7-, and 10-year periods, for portfolios varying from 100% in stocks in 100% in (intermediate term government) bonds.

Not surprisingly, while the odds of a negative return are fairly low across the board, and the odds decline further as the time horizon lengthens and the portfolio becomes more conservative. While many portfolios may still be negative after 5 years, historically over a 7-year time period, a portfolio with 60%-or-less in stocks has never had a negative cumulative return. Over a 10-year time horizon, as long as bond exposure is at least 20% (i.e., equity exposure is down to 80%), a negative cumulative return has never occurred over such a "long" time horizon; in other words, to the extent that equities were down at all, with as little as 20% in bonds the bond return was enough to fully offset any losses.

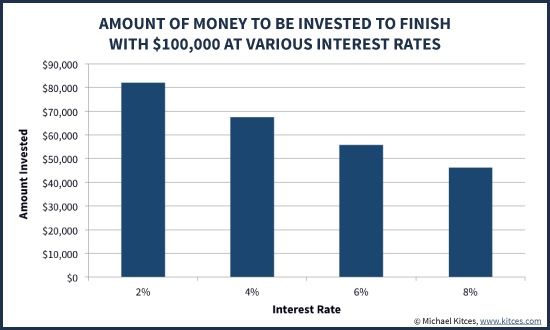

Of course, while equities have historically always recovered enough that 20% in bonds is "enough" over a 10-year time horizon, in the extreme an investor could actually guarantee that the portfolio will never have a negative return, simply by buying enough 10-year government bonds to ensure that just holding until maturity alone will replenish the entire principal. In such a scenario, even if the stock market in the aggregate went to zero, the bonds alone would still mature with sufficient value to replenish the original principal. Of course, the amount it takes in bonds to provide for that principal replacement depends on the (10-year) bond yield in the first place; the higher the yield, the less it takes in bonds to replace the principal down the road (and the more than can be invested into equities), while in today’s environment with lower yields, it takes far more, as shown in the chart below. (Chart assumes the investor simply buys 10-year zero-coupon Treasury STRIPS at the specified rate.)

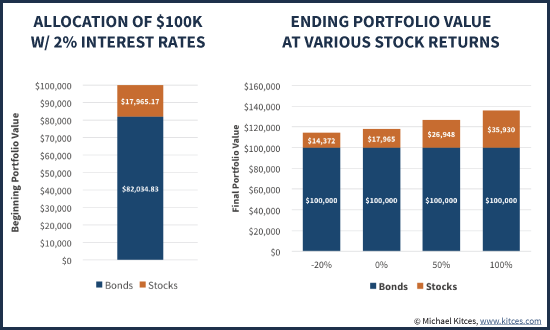

Once Treasuries are in place to secure the “floor”, the investor would simply put the rest of his/her funds into equities… at a 2% interest rate, this would require about 82% of the portfolio in bonds, and the remaining 18% in equities. As noted earlier, in this scenario the stocks could go all the way to zero, and the investor would still be protected because the bonds alone would mature at par to replace the original ($100,000) portfolio value.

In fact, even if equities were merely flat for the decade, the investor would still end out with 100% of the original principal (from bonds), plus 100% of the original investment in equities, resulting in a final value up 18% cumulatively, for a modest positive total return of about 1.67%/year. Even if equities are down 20%, there will still be a positive return for the total portfolio of about 1.35%/year! And of course if equities are up, the investor just makes even more on top of the bond return. Either way, the principal guarantee stays intact no matter what.

Of course, because a large portion of the funds were occupied by the bond allocation – especially given today’s low interest rates – the investor only gets a “modest” participation in the total upside of equities. Even in the scenario where the market grows by 100% cumulatively in a decade (an average annual growth rate of about 7% for the stocks), the overall portfolio is only up at a 3.1% average annual compound growth rate. In other words, the investor only participated in about 44% of the total upside in this bull market scenario. But then again, the investor got that upside participation with no downside risk at all, as principal itself was entirely secured by just the bonds alone. Given current Treasury yields, any investor could theoretically do this today.

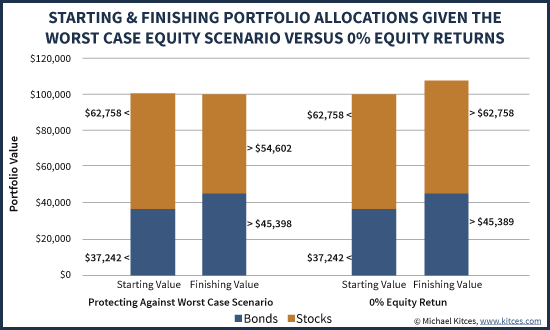

Notably, one of the caveats to the strategy of pairing Treasuries-to-replace-principal with a stock allocation is that even if stocks finish flat, the portfolio will technically be up. In order to achieve a scenario where the total return is zero when stocks are flat, the investor could choose to allocate less to bonds and more to stocks - for instance, putting in enough that even if stocks do have their worst decade ever, the remaining value in equities - plus the value of the bonds - would be enough to replace/secure the original $100,000 portfolio value. And if the equities "merely" finished flat (at a 0% return), the portfolio again would be up at least a little.

Pairing Treasury Bonds With Equity Index Options For A More Efficient Downside Guarantee

Given the challenges of cleanly aligning a guaranteed floor and equity upside by pairing together stocks and bonds directly, an alternative way to structure the transaction is to use bonds and equity index options, as the latter provide for a more effective “alignment” of upside and floor guarantee.

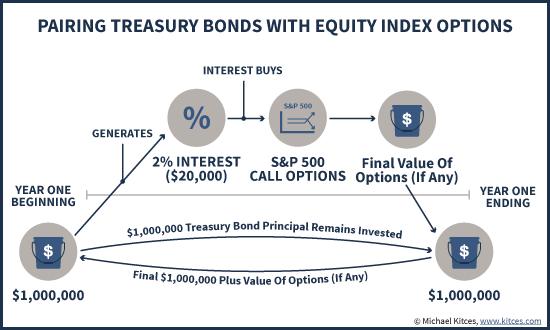

For instance, in the simplest scenario, an investor might simply buy a series of 10-year Treasury bonds, and use the annual bond interest to buy a series of 1-year at-the-money call options for the desired equity index (e.g., the S&P 500). At worst, if the market doesn’t go up for 10 years, the options will expire worthless every year, but the bonds remain to mature at par at the end of the decade, returning the target principal amount. And any year the options expire in the money, the investor participates in (at least some of) the upside.

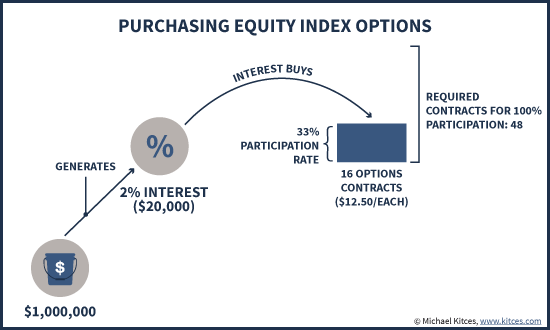

Of course, at today’s low interest rates, there’s not a lot of interest available to invest into those options. With the 10-year Treasury yielding roughly 2%, and an at-the-money call option on SPY available for $12.50 for a strike price of $210 (as of when the S&P 500 was at 2,100), an investor with a $1,000,000 portfolio could buy roughly 16 options contracts (with the 2% x $1,000,000 principal = $20,000/year of interest). Of course, it would actually take about 48 call options at a strike price of $210 to get full equity participation on a $1,000,000 account, so buying “just” 16 options contracts would give the investor an upside equity participation rate of roughly 33%.

In other words, given what today’s interest rates will bear out in buying call options, the investor effectively gets a 33% participation in the upside price movement of the S&P 500 (note: price changes only, as options don’t pay dividends!), with “no downside”, since at worst the options merely expire worthless at the end of the year and the investor buys new options again next year while bond principal remains intact (to mature at par at the end).

Since options would be purchased one year at a time in this example, each year the starting point for equity participation will “reset” to the then-current level of the index, and the participation rate itself will fluctuate up and down with then-current pricing of options (which may be more or less expensive, depending on changes in volatility along the way).

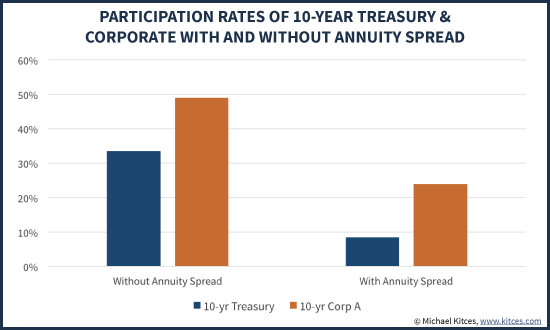

Of course, to the extent that the investor is comfortable taking a little more risk, the participation rate can be improved further. For instance, with 10-year A-rated corporate bonds (slightly greater risk of default than Treasuries) yielding approximately 2.9%, using that interest buys enough options contracts to produce a first-year participation rate of 49% instead of “just” 33%.

On the other hand, the caveat is that in the context of an equity-indexed annuity (or a structured note that functions in a similar manner), participation rates will be lower, as the insurance company needs an opportunity to make money as well, as a for-profit entity (not to mention recovering its costs of overhead and distribution). With an equity-indexed annuity, this is accomplished through an interest rate spread – in other words, while the insurance company might invest in bonds that pay 2%, it may keep 1.5% of that interest yield to cover everything from overhead to profit margins to the commissions paid to the selling agent, with only the remaining 0.5% yield going into options. Given today’s low interest rates, though, cutting out a 1.5% interest rate spread has a dramatic impact, reducing the participation rate to only 8% using 10-year Treasuries and 24% with a 10-year A-rated corporate bond.

Amplifying Participation Rates In A Low Yield World With Call Spread Caps And Monthly Averaging

Because the participation rate is driven by the number of options contracts purchased, and the free cash flow to purchase those options is derived from bond interest, the overall level of interest rates turns out to be a key factor in the potential participation rate of an equity-upside-with-downside-protection strategy. If/when/as interest rates rise, so too will available participation rates, either for equity-indexed annuities, structured notes, or for investors and advisors who wish to construct their own using bonds and options.

On the other hand, as long as interest rates stay low, both insurance companies and investors may feel forced to find other means to boost participation rates, either through strategies to increase the yield and available dollars to buy options, or to manage the (net) cost of options.

For instance, an investor might own different (e.g., lesser quality) bonds to stretch for greater yield, or move into other segments of the bond market that might otherwise generate better cash flows. The more the bond cash flows, the more money there is to buy options, and the greater the upside participation rate. In the context of equity-indexed annuities, insurance companies often use their size and scale to negotiate for better pricing on bond deals to maximize their yield. Investors can also boost their participation rates by giving up a bit on their guarantees in the first place; for instance, if guaranteeing “just” 90% of the principal is sufficient, the investor can put less money in bonds, which frees up more capital to invest over time towards options instead, resulting in more equity upside participation.

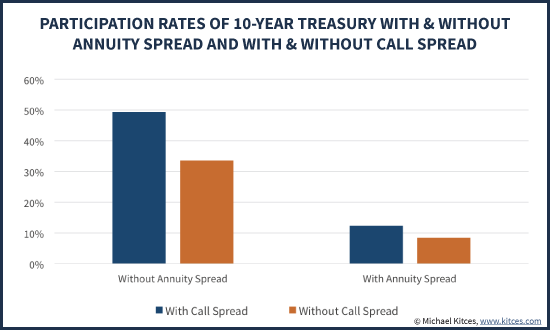

Alternatively, the net cost of options can also be reduced with call spreads, like buying an at-the-money option but selling an out-of-the-money call option at a higher strike price. The net result puts an effective cap on the maximum appreciation, but increases the participation rate along with it. For instance, a call option for SPY at a strike price of 230 costs approximately $4.00 (at the time of this writing when the S&P 500 is around 2,100), which would reduce the net cost of an at-the-money call option from $12.50 to only $8.50. In turn, this would allow a larger number of options to be purchased, but the maximum appreciation for the year would be limited to only about 9.5% (the gain from 210 to 230 on the SPY, corresponding to 2,100 to 2,300 on the S&P 500). Of course, when purchased from an equity-indexed annuity company (or a structured note) that must charge an annuity interest rate spread, participation rates will still be compressed slightly.

Notably, in the context of equity-indexed annuities in particular, insurance companies have also sought to increase participation rates by shifting from annual point-to-point strategies (i.e., participation in the one-year price return of an index like the S&P 500) to “monthly averaging” strategies instead. With monthly averaging, the investor’s return is calculated by taking the average price of the index throughout the year, comparing it to the original, and calculating the appreciation accordingly. Thus, for instance, if the market went up 12% for the year by rising 1% each month, the S&P 500 would grow from 2,100 to approximately 2,350, and the average price for the year would be about 2,225. Since 2,225 is a 6% increase over the starting level of 2,100, the monthly averaging formula would return 6%, then further adjusted by the participation rate (so if the participation rate was 75%, the final return would be 6% x 75% = 4.5%, even though the market was up 12% overall).

Ultimately, monthly averaging formulas will (on average) produce lower returns in bull markets than point-to-point structures since markets average positive returns (e.g., a normal point-to-point one-year option in this example would have applied the participation rate to 12% upside instead of only 6%). However, because the monthly averaging options contracts are generally cheaper (for this same reason about their expected returns), annuities based on them will tend to have higher participation rates; in the end, given the different combinations of upside potential and participation rates in that upside, investors may not actually see substantively different returns either way (e.g., 75% participation on 6% appreciation in a monthly average formula is similar to getting 40% participation on the 12% upside in a point-to-point formula). In many cases, which is better will simply depend on the exact path the market takes for the year - at least, if all else is held equal (though that is not always the case).

Unfortunately, though, monthly averaging options in particular generally aren’t available to consumers building their own solutions (as the versions insurance companies use are privately negotiated derivatives that aren’t traded on public exchanges for consumers to purchase); nonetheless, the remaining strategies of investing for greater bond yields, accepting diminished principal guarantees in exchange for more upside, and using call option spreads to get greater participation but with an upside cap, are all feasible for individual investors. In other words, advisors and their clients really can build their own equity-indexed annuity or structured note solutions, but without the annuity or structured note itself (though notably, this "do-it-yourself" solution also loses out on the tax-deferral treatment of annuities, which may be relevant for some clients!).

Of course, the irony of building “your own” principal guarantee is that it does mean trading in options, and watching – at least in down years – the value of those options potentially going all the way to zero. While that -100% return will by definition only be for a very small percentage of the portfolio, the fact remains that for many investors, it may actually be more psychologically comforting to not see how the sausage is made and just view a single account balance with a floor (as occurs with equity-indexed annuities and structured notes)… although as noted earlier, the interest rate spread of an annuity (or structured note) can significantly undermine the potential upside of such “packaged” floor-with-upside investment strategies in low yield environments, so that psychological comfort has a potentially significant cost trade-off!

Interesting article, Michael. I think the FIA (fixed indexed annuities, the now-preferred lingo) marketplace has been quite inventive over the past 3-4 years and would have products that would most likely out-perform the scenario you’ve painted here.

One question for you: insurance carriers use surrender charges to offset costs in the product. This could present a problem for someone needing to surrender the policy before the charges do not apply. A typical charge in the first year is around 10% of the accumulated value, or less, and declines each year after.

The question is, if rates continue to rise, in 4, 5, 6, or 7 years what will that do to a client’s principal? Would it be “worse” than surrendering an annuity with a 4-8% surrender penalty?

Thanks – always great stuff from you. Enjoyed your material in the RICP course.

Luke,

I’d be VERY curious to see any insurance carrier product that can outperform the scenarios I’m painting here. That’s not to suggest anything nefarious – it’s just that ultimately, insurance companies are subject to the same capital markets and buying substantively similar derivatives and solutions. While insurance carriers can realistically get slightly better pricing (i.e., lower transaction costs) on some forms of this implementation, it would not likely be dramatically different (and of course, the insurance company also has costs that a direct solution would not).

Regarding surrender charges, it’s worth noting that carriers don’t use surrender charges to directly offset costs in the product, for the simple reason that people who keep/hold the products don’t pay the surrender charges. The surrender charge functions primarily to repay the insurance company for any commissions that were advanced to the insurance agent up front, but haven’t yet been recovered from the ongoing interest rate spread (i.e., indirect client cost) over time. See https://www.kitces.com/blog/the-myth-of-free-no-expense-fixed-or-equity-indexed-annuities-interest-rate-spread-is-still-a-cost/ for further discussion of this.

As for the impact of interest rate increases relative to surrender charges, honestly don’t know offhand, I’d have to run the math. Remember the closer that the bonds get to maturity, the shorter their duration, and the less interest rate changes impact them in general (so the longer it takes interest rates to rise, the less it will matter). You could also manage the exposure with shorter-term bonds, though obviously that means less yield, which results in less equity participation (because there will be less interest to buy options). Same reason that equity-indexed annuities tend to have better participation rates over longer time horizons.

– Michael

My 2 cents on inventiveness – I think the investment industry could use a pull back on their creativity. It only serves to overwhelm the client and make their eyes glaze over.

Maybe some advisors would think this a justification of their employment.

I believe it leaves the client uninterested in their own future, ruins their client experience and enables them to blame their advisor or the markets for bad outcomes (behind closed doors of course).

Good article. I’ve played around with a few “roll your own” strategies through the years. It always helps me to be able to visualize the return scenarios.

For example, using the options method — where you use yields to buy at the money calls — and then sell calls at a higher amount to create an earnings cap — I believe the return graph looks like this. http://screencast.com/t/8j5YLiJvVS

Using the method where you buy x% stocks and x% bonds/CDS, the graph looks like this:

http://screencast.com/t/13mioBf3q

Looking at these now, it’s a little tough to decipher with only a few lines of explanation. But the gist is, as you have pointed out, these products are fairly easy to recreate and totally avoid associated fees.

Interesting, to say the least. I have a few questions. Assume we are dealing with clients at or over retirement age. (1) How does this stack up against immediate annuities where you are getting exposure to mortality credits in the return? (2) Doesn’t this strategy only work for clients who have no need for income, since that income is being used to purchase the calls? (3) Why would you not incorporate some type of bond laddering in the fixed income portion of the investment to take advantage of the possibility of rising interest rates, especially fast rising rates? You addressed monthly averaging but I am not sure if you are talking about a combination of intermediate bonds or just a straight 10 Year UST. Thanks

Just curious Michael if you’re discussing real returns or nominals? Particularly when you’re averaging the modest returns over a 10 year time frame of 1.65% and 1.35% (based on 82% invested in bonds)

Dale,

All nominal returns here.

No doubt the return upside isn’t huge in these examples. That’s what happens when investors want a ‘guaranteed floor’ in the midst of a low-yield low-return environment. We’re all subject to the same capital markets. :/

If you ran similar numbers with where we were even back in the early 2000s, it looks a helluva lot better. 🙂 (And indexed-annuity participation/payout rates were better back then too, for the same reason)

– Michael

Great thanks for that Michael. As always a great article.

Alas, times change and the future is uncertain. A fact every advisor forgets when they point to charts denoting past returns of the market like they are numbers to swear by.

Couldn’t we make it simpler? Buy a 10 yr CD at 2.75% that compounds quarterly (I think Ally Bank has one as of this date) and use the interest reinvestment option. Invest the discounted difference in an all equity globally diversified portfolio.

Say you have $1M to invest. Spend $916K on the CD (the NPV of the $1M in 10 years at 2.75%), invest the $84K in the equity portfolio.

Using today’s interest rates and assuming the previous 10 years returns for such a globally diversified equity portfolio at an annualized 9.6%, you have $1.1065M in 10 years, 4.07% annualized

I’m not considering tax issues… which have to be considered eventually in either case. This is more of a ‘Roth’ type investment you might say.

This seems simple and straightforward, no?

Actually, my calc had the wrong periods set. The 84K at 9.6% become $210K. So the final result is $1.21M or 1.93% annualized. The floor remains.

Michael,

Yes, my early examples basically illustrated this exact approach. Put $X in a CD that matures back at full value, take the rest and put it in stocks.

Though if you ‘only’ get 1.93% annualized on a portfolio that was growing at 9.6% annualized, you basically had a 20% participation rate. You’ll probably find you can do a bit better on the participation rate with options (which is why I went there next in the article).

– Michael

Great article. VERY few people if any implement a similar strategy compared to those that buy an equity indexed annuity. Recreating these strategies and variable annuity guarantees really help clients realize there is no free lunch in most investments. If this type of product was truly valuable, we could have an easy to use, prepackaged, low cost, low fee, investment option for fee only RIAs, investment advisors that don’t use insurance products, and people who DIY at discount brokerages.

Good analysis and I think this shows that equity indexed annuities really show that the “emperor isn’t wearing any clothes”. If you need 10 years of principle guarantee and you are talking about a 30-40% capture rate of the S&P500 (lets assume 10% total return so likely 8% long term return), you are looking at ~2-3%

It also makes sense, you are trying to construct a “risk free” return so in a efficient world where arbitrage gets rid of mispriced things, your expected return SHOULD be the yield on your government bonds. VERY SMALL! In other words, it doesn’t matter how you bake the cake, if you are trying to get a riskless return, you will always end up with the yield on a government bond.

I wonder how many people would buy an Equity Indexed Annuity if they had to post the expected return that matches (or is worse after fees) of a 10 year government bond?

Great article! Thanks Michael.

Stephen,

Thanks for the kind words.

Strictly speaking, the expected return here with arbitrage still wouldn’t necessarily be the yield of your government bonds. You DO have a risk of underperforming those bonds (hypothetically you could get a 0% return). So even in an otherwise efficient market, your expected return would be something more than government bonds (of comparable yield and duration) simply to recognize the risk premium over bonds for the potential that you could get a return between 0% and that bond. But it would still be much lower than the expected return of equities.

– Michael

None of the examples presented included any management fees. Do you work for free? If you take out 1%/year (or even 50-bp/yr) for your “work,” then I believe your strategies all fail when compare to a “good” indexed annuity or a “good” structured note (“good” being the operative word here). The Structured Notes and insurance companies both have the benefit of pairing the pieces together in-house, without additional transaction costs. They also benefit by having those invested dollars “in house” till the product matures (helps bank asset ratios). I actually transferred most of my managed accounts back to commissioned accounts to buy structured notes because it was much better for the client.

Is this a good strategy to use temporarily with “new” investment funds when there is concern that the market is priced too high in general? No return (options expire out of money) is better than losses if prices go down and some of the upside will be received if the market does better than expected. The funds can be allocated more traditionally when one is more comfortable that the market is not at the peaks. Or alternatively, new funds can be invested to better diversify. Good Article!