Executive Summary

Buy-sell agreements are a common succession planning tool for business owners where, upon a triggering event like the death of one owner, the surviving owners have either the option or the contractual obligation to purchase the deceased owner's shares of the business. Traditionally, buy-sell agreements are structured either as cross-purchase agreements (where the surviving owners buy the deceased owners' shares directly from their estate) or entity-purchase agreements (where the business itself redeems the deceased owner's shares).

The agreements are usually funded by life insurance policies on each owner: cross-purchase agreements are owned by each owner on every other owner, and entity-purchase agreements are owned by the business on each owner. This has generally made entity-purchase agreements preferable for businesses with more than a small handful of owners, since an entity-purchase agreement only requires the purchase of one insurance policy per owner, while the number of policies needed for a cross-purchase agreement increases exponentially as more owners are added to the group.

Which makes it notable that, in a recent ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case Connelly v. Internal Revenue Service, the court ruled that life insurance proceeds paid to an entity-purchase agreement increase the business's value for the purposes of determining the taxable estate of the deceased owner, with the IRS arguing (and the court agreeing) that if a hypothetical third-party buyer were buying the shares, they would be willing to pay for them based on the full value of the company… including the life insurance proceeds.

As a result, business owners who have implemented entity-purchase agreements face the prospect of the insurance proceeds used to fund those agreements being at least partially included in their taxable estate, which, at a top Federal estate tax rate of 40%, could result in a significantly higher estate tax liability for owners whose estates either exceed the current $13.61 million estate tax threshold or for whom inclusion of the insurance proceeds would bump them over the threshold. And with the threshold scheduled to be reduced by 50% when the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act expires after 2025, many more business owners stand to be impacted by the Connelly decision in the near future.

The challenge of 'fixing' an entity-purchase agreement that may subject owners to higher estate tax is that it isn't possible to simply move ownership of the business-owned insurance policies to the business owners themselves, because doing so could trigger "transfer for value" rules that make the proceeds taxable on receipt for income tax purposes. However, one exception to the transfer-for-value rules makes it possible to transfer a life insurance policy to a partnership owned by the insured person – which potentially opens the door for business owners to create a new "special-purpose buy-sell insurance LLC" that is treated as a partnership for tax purposes and assumes ownership of the insurance policies, which would serve the purpose of moving the policies off the books of the original business without running afoul of the transfer-for-value rules.

The caveat, however, is that despite having recognized such insurance LLCs as legitimate in the past, there's no guarantee that the IRS will continue to do so – and in the wake of the Connelly ruling, they could potentially scrutinize new and existing insurance LLCs, challenging the legitimacy of ones that may lack a valid business purpose – which, if successful, could cause the LLC to be disregarded and the insurance proceeds to become taxable, either to the estate of the deceased owner for estate tax purposes and/or to all of the business owners for income tax purposes!

The key point is that while an insurance LLC may make it possible to transition away from an existing entity-purchase agreement to one that won't create new estate tax exposure without unwinding the entire buy-sell agreement and starting from scratch, doing so does add to the complexity of the business succession plan and introduces potential risks that it won't succeed in meeting the business owners' goals. Which, for some owners, means it might be preferable to simply start anew with a traditional cross-purchase agreement – but for others, who are willing to accept the risks and navigate the challenges of drafting and adhering to an insurance LLC, it may still be worth it for the potential for estate tax savings and flexibility.

The Mechanics Of Business Buy-Sell Agreements

For the owners of small, closely-held businesses, the idea of succession planning is partially about choosing someone to hand off the reins of the business to when an original owner retires, but also partially about ensuring that there is an orderly transition of ownership in the event of an owner's unexpected death or disability. Because for estate planning purposes, an ownership stake in a small business isn't all that different from shares of stock in a large company: The decedent's ownership passes via the terms of the instructions they provided during life – e.g., by the terms of a will, a trust, or a contractual agreement – or, absent any instructions, the intestacy statutes of the state where they resided.

A person who spent their lifetime working to build a business may want their heirs to benefit from the fruits of that ownership. But in many cases, it doesn't make practical sense to leave a stake in a small business directly to a spouse, children, or grandchildren. For one thing, a spouse or child of the deceased owner might have no interest in running the 'family business' – they'd simply rather have the cash value of the decedent's ownership shares without the responsibility of owning (and typically also working in) the business itself. Likewise, the business's other owners may want to have control over who gets to share in the ownership pool rather than taking the chance that whomever the decedent owner has named as the heir to the business will be a good fit among the owners (or allowing that person to potentially turn around and sell their stake to whomever they please).

And so small business owners often enter into a buy-sell agreement with their fellow partners or shareholders in the business. At a high level, a buy-sell agreement is a contract that gives one party the right or obligation to buy another party's share of ownership in a business when a triggering event occurs (usually the death or incapacity of the seller, though other events like retirement or bankruptcy could also trigger the agreement). In practice, buy-sell agreements give business owners the right of first refusal for a deceased or incapacitated co-owner's shares, ensuring that the owners won't lose control over a portion of the business in the case of an unforeseen event.

The actual mechanics of the buy-sell agreement depend on whether it is structured as a cross-purchase agreement or an entity-purchase agreement. In a cross-purchase agreement, the buy-sell transactions are between each individual owner – that is, when one owner dies or is incapacitated, their ownership stake is sold directly to the other owner(s) of the business. In order to get the funding needed to buy out another owner's shares, each owner purchases life insurance on each of the other owners that will pay out on the death or permanent incapacitation of that owner. That way, each owner is assured to have liquid funds available to fulfill their end of the buy-sell agreement in the event that it's triggered.

Example 1: Kendall and Logan are each 50% owners of WayCo, a business worth $1,000,000. The 2 owners set up a cross-purchase agreement with each other where, in the event that either owner dies, the surviving owner will pay the deceased owner's estate $500,000 for their 50% share of the business. Kendall and Logan then each purchase a $500,000 permanent life insurance policy on the other.

The following year, Logan passes away unexpectedly. Kendall receives the $500,000 death benefit from his life insurance policy on Logan, which he then uses to purchase Logan's shares from Logan's estate per the terms of the cross-purchase agreement.

In an entity-purchase agreement (also known as a stock redemption agreement), instead of the business owners buying and selling each other's ownership shares, it is the business that buys the shares of the deceased or incapacitated owner. Likewise, instead of the owners purchasing life insurance on each other to fund the agreement, the business itself owns and is the beneficiary of life insurance on each of the owners to fund the entity-purchase agreement.

Example 2: Rather than use a cross-purchase agreement, Kendall and Logan from Example 1 decide to use an entity-purchase agreement. So, instead of each owner agreeing to purchase each other's shares, WayCo will buy either owner's shares for $500,000 in the event of their death or incapacity. To fund the agreement, WayCo will purchase $500,000 life insurance policies on both Kendall and Logan.

Now, when Logan passes away, WayCo receives the $500,000 death benefit from the insurance policy on his life, and the company pays the proceeds to Logan's estate in exchange for his share of the business.

Pros And Cons Of Cross-Purchase Vs Entity-Purchase Agreements

Notably, it doesn't matter from an economic perspective whether a buy-sell agreement is structured as a cross-purchase or an entity-purchase agreement. In both cases, the estate of the deceased or incapacitated owner receives the same amount of cash for their share of the business, and in both cases, the remaining owners' stakes in the business remain the same.

For instance, in both Examples 1 and 2 above, after the buy-sell agreement is executed, Logan's estate receives $500,000 in cash for his shares, and Kendall is left as the 100% owner of WayCo (with his stake now worth $1 million).

However, there are some key differences between cross-purchase and entity-purchase agreements that make the distinction important from a planning perspective.

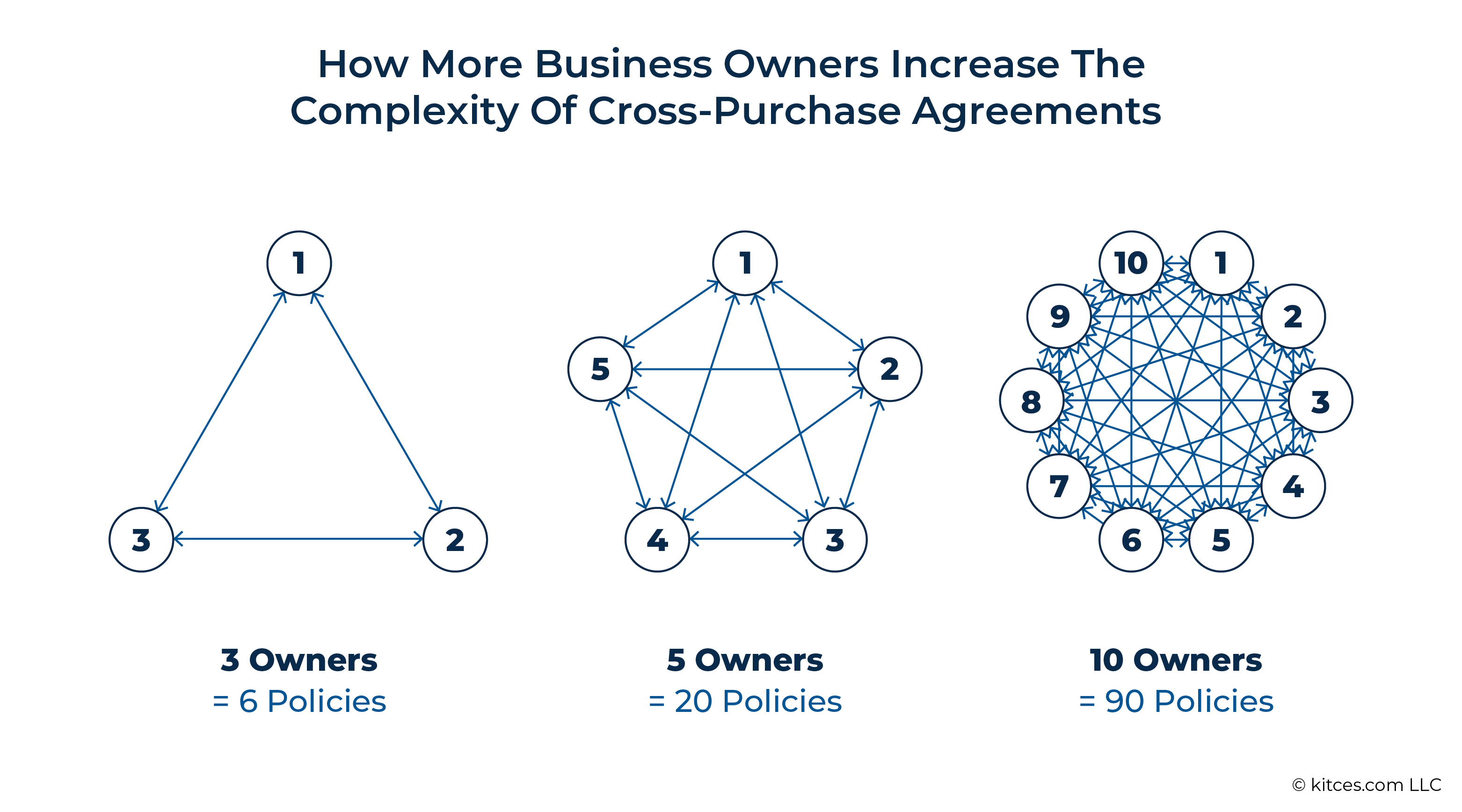

The first has to do with complexity. For a business with only 2 or 3 owners, a cross-purchase agreement and an entity-purchase agreement require roughly the same amount of effort in setting up and maintaining the plan. However, as more owners get involved, the complexity of a cross-purchase agreement gets exponentially higher: Since each owner needs to buy life insurance on every other owner, a cross-purchase agreement for a company with n owners requires the purchase of n × (n – 1) separate life insurance policies.

So, as shown below, while a cross-purchase agreement for a company with 3 owners requires buying 6 life insurance policies, adding just 2 more owners for 5 total policyholders raises the number of policies to 20, while adding another 5 owners for 10 total requires 90 different life insurance policies – each of which would need to be updated any time there is a new or departing owner, when anyone's ownership shares increase or decrease, or when the company is re-valued.

All of which can make cross-purchase agreements untenable for a company with more than a small handful of owners because of the sheer complexity of maintaining the agreement and accompanying insurance policies, making an entity-purchase agreement (which only requires 1 insurance policy per owner) a more attractive option.

Another factor is the cost of the insurance used to fund the cross-purchase agreement. Because life insurance gets more expensive the older or less healthy the insured is, a policy on a 65-year-old partner will usually cost much more than one on a 30-year-old partner. Which means that if there is a combination of younger/healthier and older/sicker owners, the different partners in the cross-purchase agreement could be required to pay drastically different premiums on their policies. Although the company can opt to reimburse the owners for their premium payments (either in the form of a bonus or a dividend, either of which is taxable to the owner), that just adds additional complexity to the arrangement.

Which is why the entity-purchase structure of a buy-sell agreement has gained more favor among owners who want to avoid the numerous complications of cross-purchase agreements, especially for those who own their businesses with a larger group of other owners. The entity-purchase structure does have some downsides; for example, unlike in a cross-purchase agreement, the surviving owners in an entity-purchase agreement don't receive a step-up in basis on the deceased owner's shares. Additionally, the business needs to comply with specific "notice-and-consent" requirements of IRC Section 101(j) to avoid the life insurance death benefit being taxable to the business. Even so, these downsides have been generally seen by business owners as minor enough to be outweighed by the benefits of the entity-purchase agreement's simpler structure.

How Connelly V. IRS Impacts Entity-Purchase Buy-Sell Agreements

A recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court introduced yet another wrinkle into the planning considerations for buy-sell agreements. In Connelly v. Internal Revenue Service, the court unanimously decided that life insurance proceeds paid to a business pursuant to an entity-purchase agreement increase that business's value for estate tax purposes, introducing enormous estate tax implications for business owners using entity-purchase buy-sell agreements.

Background Of The Connelly Case

The Connelly case arose after a business owner named Michael Connelly, who owned 77.18% of a building supply corporation (with his brother owning the remaining 22.82%), passed away, triggering an entity-purchase agreement that provided that the company would buy Michael's ownership shares from his estate after his death. Although the agreement had stipulated for the company to obtain an outside appraisal to determine how much it should pay for the shares, the estate and surviving owner decided on a less formal approach, agreeing on a value of $3 million for Connelly's shares (representing 77.18% of the company's total valuation of $3.89 million) without taking the step of getting an outside valuation. The company had owned a $3.5 million life insurance policy on Connelly, so it used $3 million of the death benefit proceeds to purchase Connelly's shares (leaving the remaining $0.5 million in the business).

Connelly's estate subsequently reported the value of his shares at $3 million (i.e., the agreed-upon price that the company paid to redeem the shares) on his estate tax return. But upon auditing the return, the IRS disputed that number, saying that the business's value also needed to include the amount of the insurance proceeds used to buy Connelly's shares. The estate did obtain an outside valuation for the business during the audit, which assessed the firm's value (without the life insurance proceeds) at $3.86 million, but the IRS maintained that, for estate tax purposes, the business's value was actually $6.86 million – that is, $3.86 million (the business's assessed value) + $3 million (the life insurance proceeds received by the business that were used to redeem Connelly's shares from the estate). The impact of including the life insurance proceeds in the firm's valuation amounted to an additional $889,914 in estate tax owed by Connelly's estate.

Connelly's estate appealed the IRS's decision on the basis of 2 main arguments:

- That the entity-purchase agreement had 'fixed' the value of the shares for estate tax purposes at $3 million (the amount that was actually paid for the shares); and

- That the obligation created by the entity-purchase agreement for the company to buy Connelly's shares effectively created an offsetting liability that canceled out the value of the life insurance proceeds.

However, the courts rejected both arguments. On the first point, the lower courts ruled that the entity-purchase agreement itself couldn't be used to set the shares' value for estate tax purposes, because the agreement hadn't included a "fixed or determinable price" that could be used to set the business's value at a specific amount (and anyway the owners hadn't even followed the agreement's own requirements to obtain an outside valuation but instead informally agreed on a $3 million price for the shares, diminishing the argument that the agreement itself should have any bearing on how the shares should be valued). This was so clearly true that the Connelly estate didn't even bother appealing this point to the Supreme Court.

But it was the second argument that was central to the Supreme Court's ruling and that will have major implications for other business owners with similar entity-purchase agreements. The court upheld the lower courts' rulings that, for estate tax purposes, a business's obligation to buy an owner's shares pursuant to a buy-sell agreement does not offset the value of the life insurance proceeds paid to the business, with the reason being that if a hypothetical third-party buyer were buying the shares, they would be willing to pay for them based on the full value of the company including the life insurance proceeds.

The Economic Logic Behind The Supreme Court's Ruling

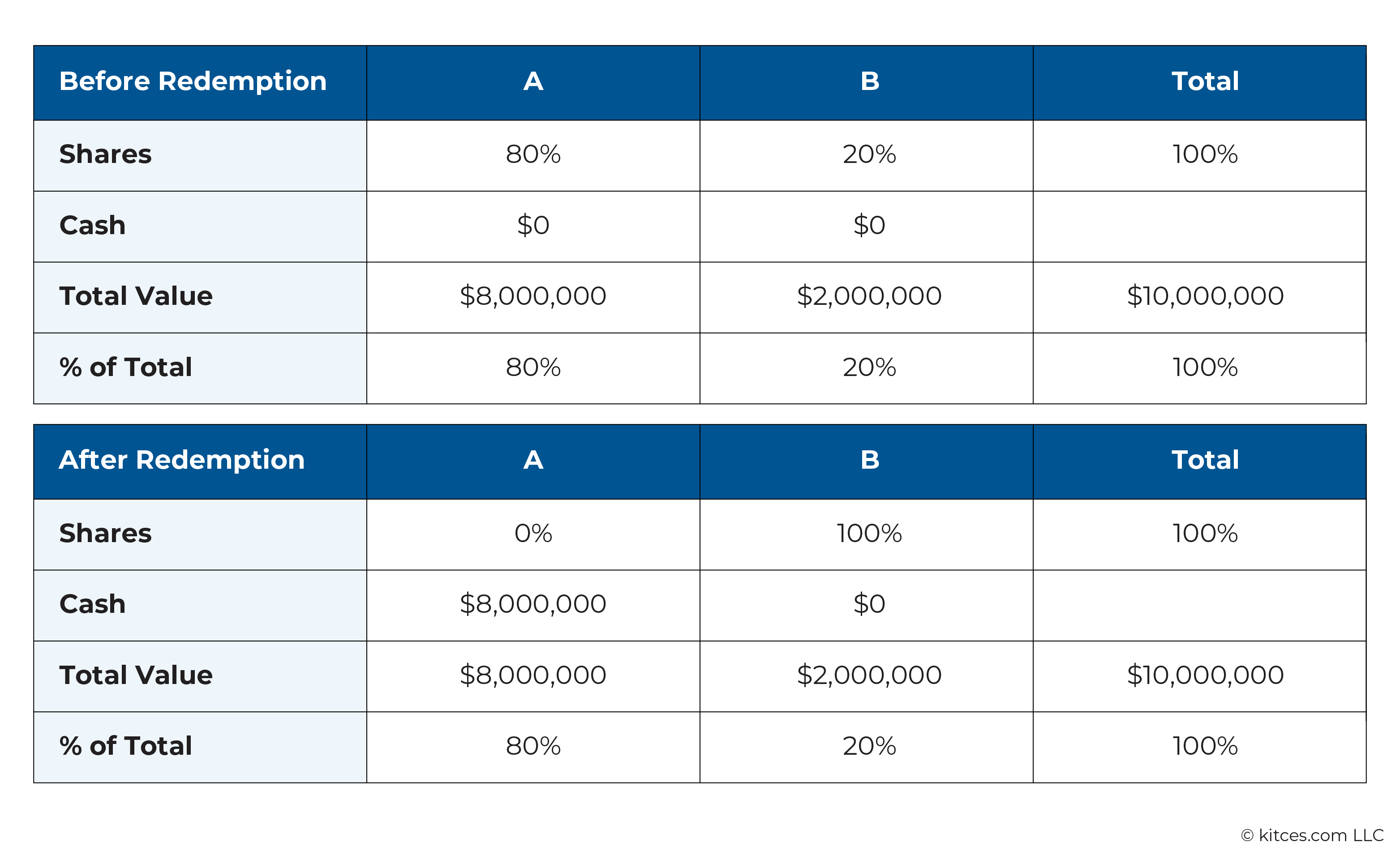

The Supreme Court's ruling might seem a little counterintuitive, so it's worth working through the economic logic supporting its decision. Imagine there is a business worth $10 million, with Owner A owning 80% of the business and Owner B owning 20%. If the business redeemed Owner A's share for its fair market value, Owner A would receive 80% × $10 million = $8 million in cash, after which Owner B would now be the sole owner of the business (which is now worth $2 million since it just paid $8 million for A's shares).

As shown below, both owners are in the same place economically before and after the transaction: A has exchanged his $8 million worth of shares for $8 million in cash, while the value of B's shares remains at $2 million. Meanwhile, they both own the same relative share of the entire 'pot' of funds (80% for Owner A, 20% for Owner B). In other words, Owner A's share redemption has done nothing to change either owner's economic position.

If a hypothetical third-party buyer were to purchase Owner A's shares prior to the company redeeming them, that buyer would pay up to $8 million for the shares – i.e., the amount they would expect to pay to own 80% of a $10 million company. Even if the hypothetical buyer knew that the company planned to redeem the shares at fair market value, there would be no reason to value them any less on account of that fact, since the buyer would be in the exact same economic position before and after the redemption. All of which confirms that the fair market value of Owner A's stake in the company is indeed $8 million.

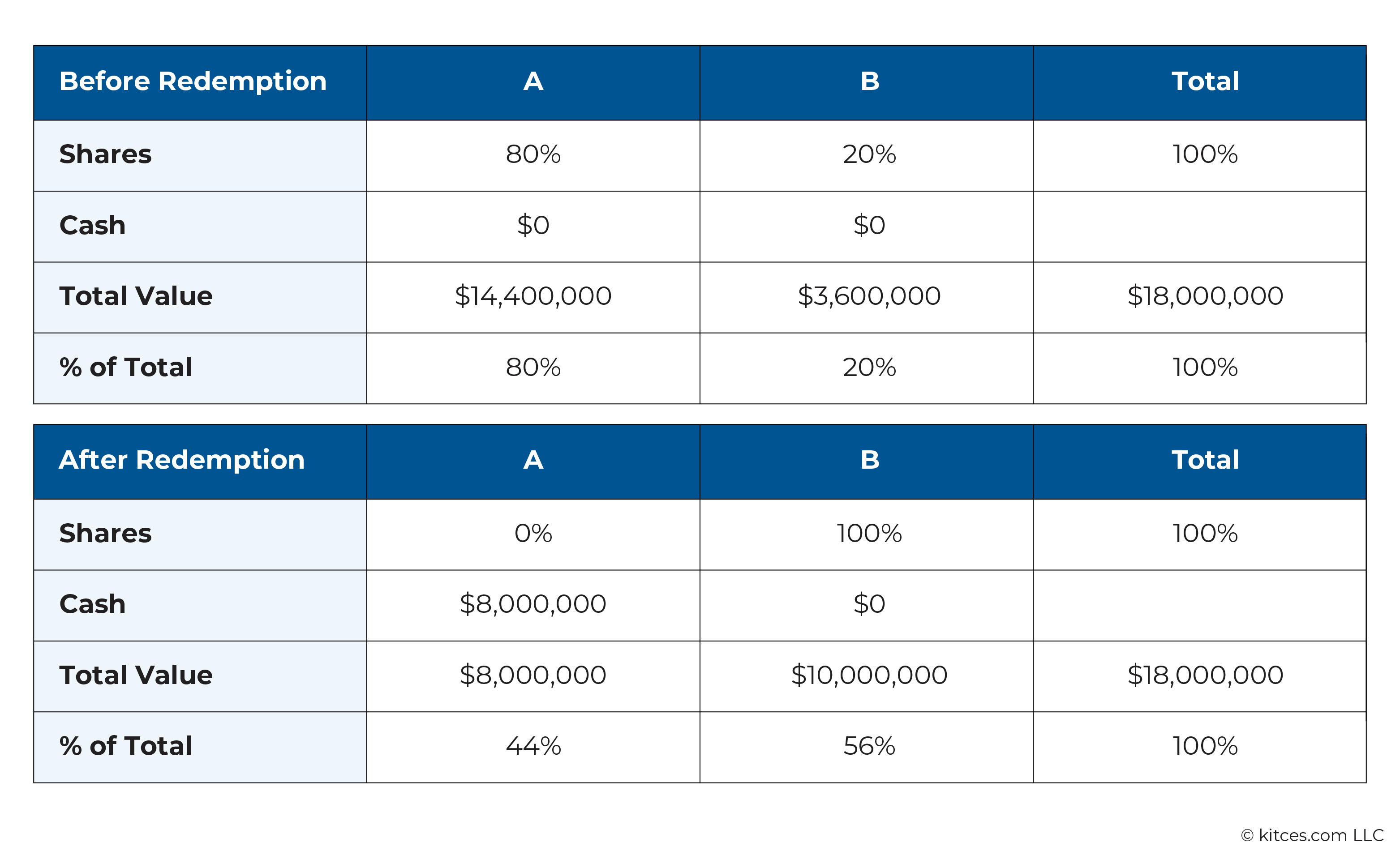

Now imagine there is an entity-purchase agreement in place where, if Owner A dies, the business will redeem Owner A's shares from his estate. And to fund the agreement, the business owns an $8 million life insurance policy on Owner A. Let's say that Owner A dies: The business is now worth $18 million (the original $10 million, plus the $8 million in life insurance proceeds). The business purchases Owner A's shares for $8 million. Now, Owner A's estate has $8 million in cash, and Owner B has 100% ownership of the business (which is worth $10 million after the redemption).

But as shown below, in this case, the 2 owners are no longer economically equivalent to where they were before the transaction: While Owner A's 80% stake in the business was worth $18 million × 0.8 = $14.4 million prior to the redemption, A's estate only received $8 million for his shares. Meanwhile, Owner B's shares, which were worth $18 million × 0.2 = $3.6 million prior to the redemption, are now worth $10 million. Which violates the principle, from the original example above, that both owners' economic position should be the same before and after the share redemption: Owner A went from owning 80% of the total 'pot' of funds prior to the redemption to owning only 44.4% afterward, while Owner B's share of the 'pot' rose from 20% to 55.6%.

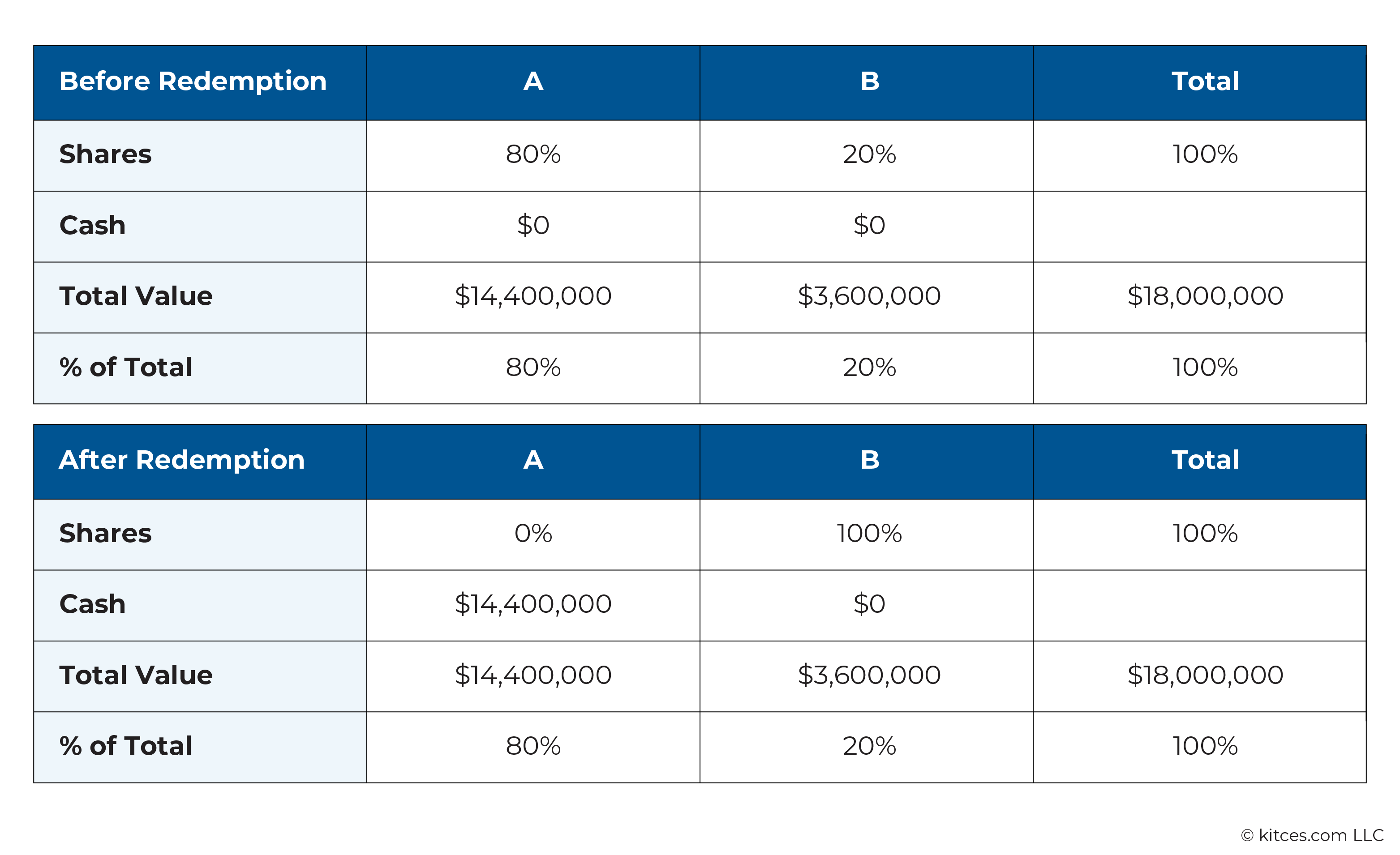

In this case, if a hypothetical third-party buyer were going to purchase A's shares from his estate knowing that the business planned to redeem the shares at fair market value, it wouldn't make sense to value the shares at $8 million, since that only represents $8 million ÷ $18 million = 44.4% of the company's total value. In reality, they should expect Owner A's shares to be worth 80% of the company's value, or $18 million × 80% = $14.4 million, which, as shown below, would result in both owners being in the same economic position before and after the redemption:

Which is why it doesn't make sense to treat the business's obligation to redeem Owner A's shares as a liability that offsets the value of the life insurance proceeds, as the business owners in the Connelly case tried to argue. If the company were only worth $10 million immediately before the share redemption (i.e., the value of the company without including the insurance proceeds), the total 'pot' of funds after the redemption should also be worth $10 million, with each owner owning the same percentage of the 'pot' before and after the redemption. Instead, there's an $18 million 'pot' of funds left over after the redemption, which means that the pre-redemption value must also be $18 million – that is, the value of the company including the insurance proceeds. And because Owner A's shares were worth 80% of that pre-redemption value from the perspective of a neutral buyer, the fair market value of his shares for estate tax purposes is $14.4 million (regardless of the fact that the company only paid $8 million to redeem them).

Likewise, in the Connelly case, the IRS argued (and the Supreme Court agreed) that because total 'pot' of funds after the redemption of Connelly's shares was worth $6.86 million – $3.86 million for the business itself plus the $3 million in cash paid to Connelly's estate to redeem his shares – the business's value must have been $6.86 million before the redemption in order to uphold the principle that neither shareholder's economic position could have changed as a result of the redemption. And because a third-party buyer would have expected to receive an amount equal to Connelly's 77.18% stake in the company as fair market value for redeeming the shares, the Supreme Court upheld the IRS's argument that Connelly's shares in the business at the time of his death had a value of $6.86 million × 0.7718 = $5.29 million for estate tax purposes, i.e., the value actually reflecting his 77.18% ownership in the business – including the life insurance proceeds – upon his death.

Implications of the Connelly Decision

What's clear in the wake of Connelly is that the way business owners commonly think of life insurance proceeds used to fund entity-purchase buy-sell agreements (i.e., that they're somehow separate from the rest of the business's assets and can be effectively canceled out for estate tax purposes because they're earmarked for the redemption of the deceased owner's shares) is fundamentally different from the way the IRS thinks of them. In the IRS's view, insurance proceeds are simply a part of the business's total value and cannot be offset by any obligation to purchase shares.

With the estate tax exemption currently at $13.61 million per individual in 2024, many business owners' estates fall under the threshold where estate tax would become an issue whether or not business-owned life insurance proceeds are included in their businesses' value for estate tax purposes, and for them, the distinction doesn't really matter one way or the other. But for those whose estates do surpass the estate tax threshold (or for those who would be bumped over the threshold by including insurance proceeds), it's a big deal: As mentioned above, the difference in estate tax owed in the Connelly case was nearly $890,000. And with the estate tax threshold set to be reduced by 50% after 2025 with the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (to $6.8 million in 2024 dollars), many more business owners with lower business and estate values stand to be affected by this case in the years to come.

It may be tempting to seize on the fact that the parties in the Connelly case neglected to follow their own buy-sell agreement's requirements to obtain an outside valuation for the business and instead made their own informal 'handshake' valuation. Would that mean that, as long as a business does abide by its agreement's terms, it would be safe to use that agreement's valuation to 'freeze' the business's value for estate tax purposes?

Unfortunately, the Connelly case seems to open the door for the IRS to challenge a business valuation even if it's laid out in the entity-purchase agreement and fully adhered to by the business and its owners.

Specifically, IRC Sec. 2703 lays out several requirements that purchase agreements must adhere to in order for the business value set forth in the agreement to be allowed to be used for estate tax purposes. One of those requirements is that "Its terms are comparable to similar arrangements entered into by persons in an arms' length transaction".

But if the IRS's argument (as sanctioned by the Supreme Court in Connelly) is that a third-party buyer would, in fact, include the value of life insurance proceeds in the price they would be willing to pay for the deceased owner's shares, then it would be difficult to argue that the terms of any entity-purchase agreement are, as required by Sec. 2703, "comparable to similar arrangements entered into by persons in an arms' length transaction" if they didn't include the life insurance value. And so it would seem that, in the wake of Connelly, potentially all business owners with entity-purchase agreements (who are also subject to estate tax) could be required to include the value of any life insurance proceeds received by the business in the value of their estate.

Nerd Note:

One possible silver lining to the Connelly case's ruling is that the increase of a business's value for estate tax purposes can create a large capital loss for income tax purposes. In the example of the parties in the Connelly case, Connelly's estate redeemed his shares to the business for $3 million, but it was later determined that their value for estate tax purposes was $5.29 million. Because the basis of inherited assets is stepped up (or down) to the assets' value as determined for estate tax purposes, the basis of Connelly's shares for his estate was therefore also $5.29 million – which means that the shares' sale for $3 million created a capital loss of $2.29 million that the estate and its beneficiaries could use in future years to offset other income. If they somehow managed to use the entire loss to offset income that would have been taxed at the top 37% Federal marginal rate, it would be worth $2.29 million × 37% = $847,300, or nearly as much as the additional estate tax they owed due to the insurance proceeds being included in the business's value!

Planning Strategies To Avoid Estate Tax On Existing Business Buy-Sell Agreements

For business owners working on building a buy-sell agreement from scratch, the estate tax implications raised by the Connelly case might raise the question of whether it's best to avoid entity-purchase agreements entirely. For example, a company could instead use a cross-purchase agreement where any life insurance proceeds go directly to the decedent's fellow owners and not to the business itself, meaning the business's value would not be increased for estate tax purposes. (In fact, the Supreme Court's majority opinion explicitly noted that the business owners in question would have avoided having Connelly's life insurance proceeds included in the business's value if they had used a cross-purchase instead of an entity-purchase agreement.)

But if a business already has an entity-purchase agreement in place, then switching to a cross-purchase agreement is harder to pull off. In an ideal world, it would simply be a matter of changing the owner and beneficiary of the life insurance policies used to fund the agreement from the business to its owners. In practice, though, that doesn't work for 2 main reasons.

First, as mentioned above, the number of life insurance policies required for a cross-purchase can be much higher than for an entity-purchase agreement, so there wouldn't be enough policies to go around when changing from one agreement to another if the business owners owned the policies directly. For example, a business with 5 owners would require 5 insurance policies owned by the business under an entity-purchase agreement, but it would need a total of 20 policies collectively owned by the owners for a cross-purchase agreement, requiring (at least) 15 new policies to be issued in order to fund the agreement.

Second, transferring life insurance policies from the business to its owners would likely run up against the "transfer for value" rules governed by IRC Sec. 101(a)(2), which require the death benefits from a life insurance policy (which are typically income tax-free to the recipient) to become taxable if the policy is transferred or assigned to anyone who is not either 1) the person insured by the policy; 2) a partner of the insured; 3) a partnership in which the insured is a partner; or 4) a corporation in which the insured is a shareholder or officer.

So there are 3 main challenges for business owners to overcome in 'fixing' a buy-sell agreement that might cause estate tax issues in the wake of the Connelly decision:

- Moving the life insurance policies used to fund the agreement off the company's balance sheet so the death benefits aren't included in the business's value for estate tax purposes;

- Navigating the transfer-for-value rules to avoid having the insurance proceeds become taxable after being transferred; and

- If at all possible, keeping the existing life insurance policies in force to avoid the expense and complication of buying entirely new insurance to fund the buy-sell agreement.

The Special Purpose Buy-Sell Insurance LLC

One way that business owners can move existing life insurance policies off the business's books without either blowing up the buy-sell agreement or triggering transfer-for-value issues is to use a "Special Purpose Buy-Sell Insurance LLC". With this strategy, the owners create a new LLC (separate from the original 'operating' company) that will become the owner and beneficiary of the life insurance policies used to fund the buy-sell agreement.

The strategy works in principle because, as noted earlier, the transfer-for-value rules specifically exclude any partnership in which the insured is a partner. Meaning that, as long as the LLC elects to be taxed as a partnership, it can receive the life insurance policies without their death benefits becoming taxable to the recipients. Meanwhile, since the operating company is no longer the owner nor the beneficiary of the policies, none of the owners will need to include any of the life insurance proceeds in the business's value for estate tax purposes.

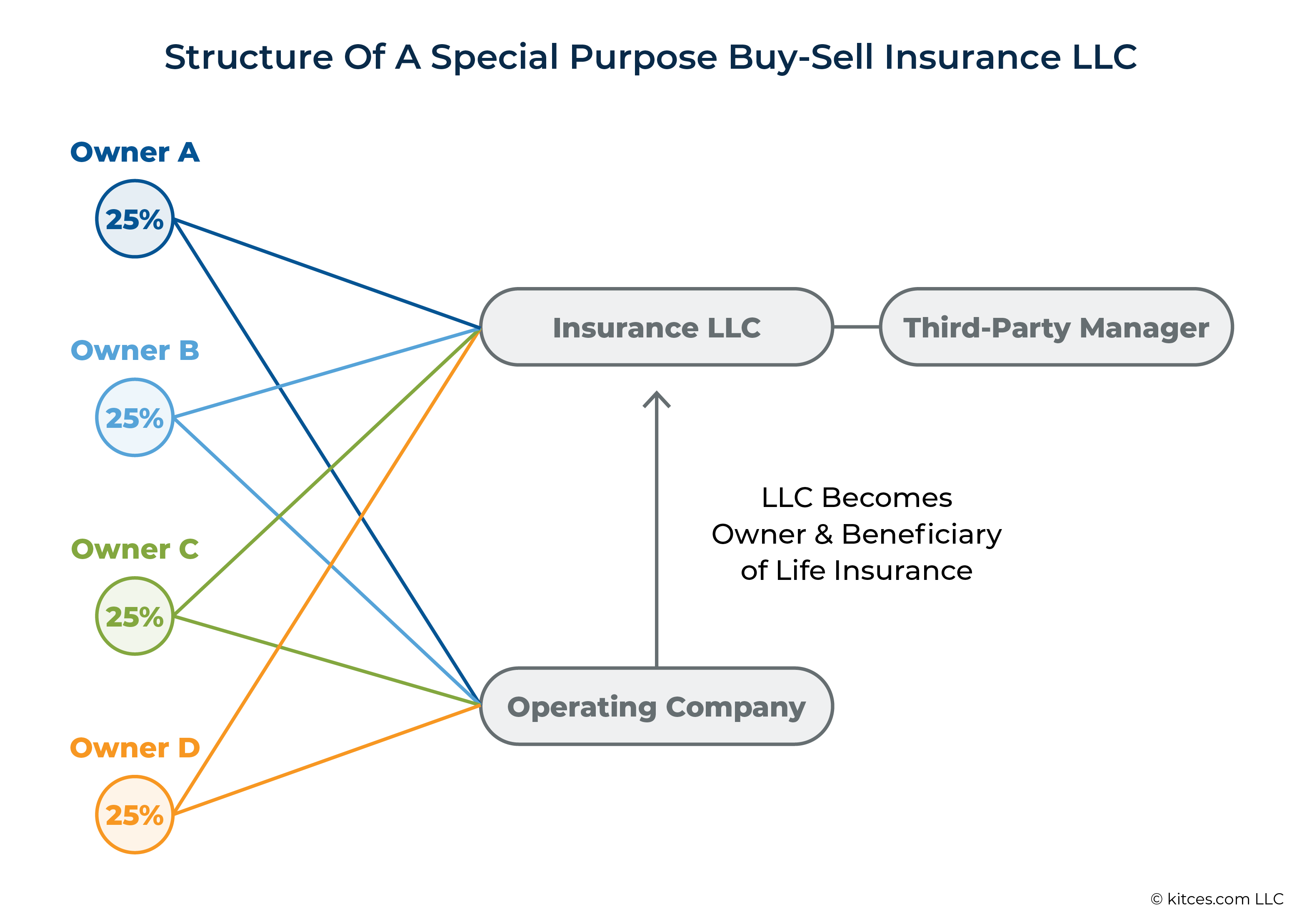

In practice, each of the owners would own a slice of the insurance LLC proportionate to their ownership share of the original operating company. The graphic below illustrates this, with 4 hypothetical owners who each own 25% of both the original operating company and the insurance LLC. The LLC would become the owner and beneficiary of the insurance policies used to fund the buy-sell agreement, although the operating company could continue to pay premiums on behalf of the owners going forward (which would be taxed as compensation to each owner, as was the case when the policies were owned by the company itself). Importantly, the business owners would need to hire a third party-manager, such as a bank or corporate trustee, to manage the LLC and its assets in order to avoid having any "incidents of ownership" that would cause any insurance proceeds to be included in the insured's estate under IRC Sec. 2042.

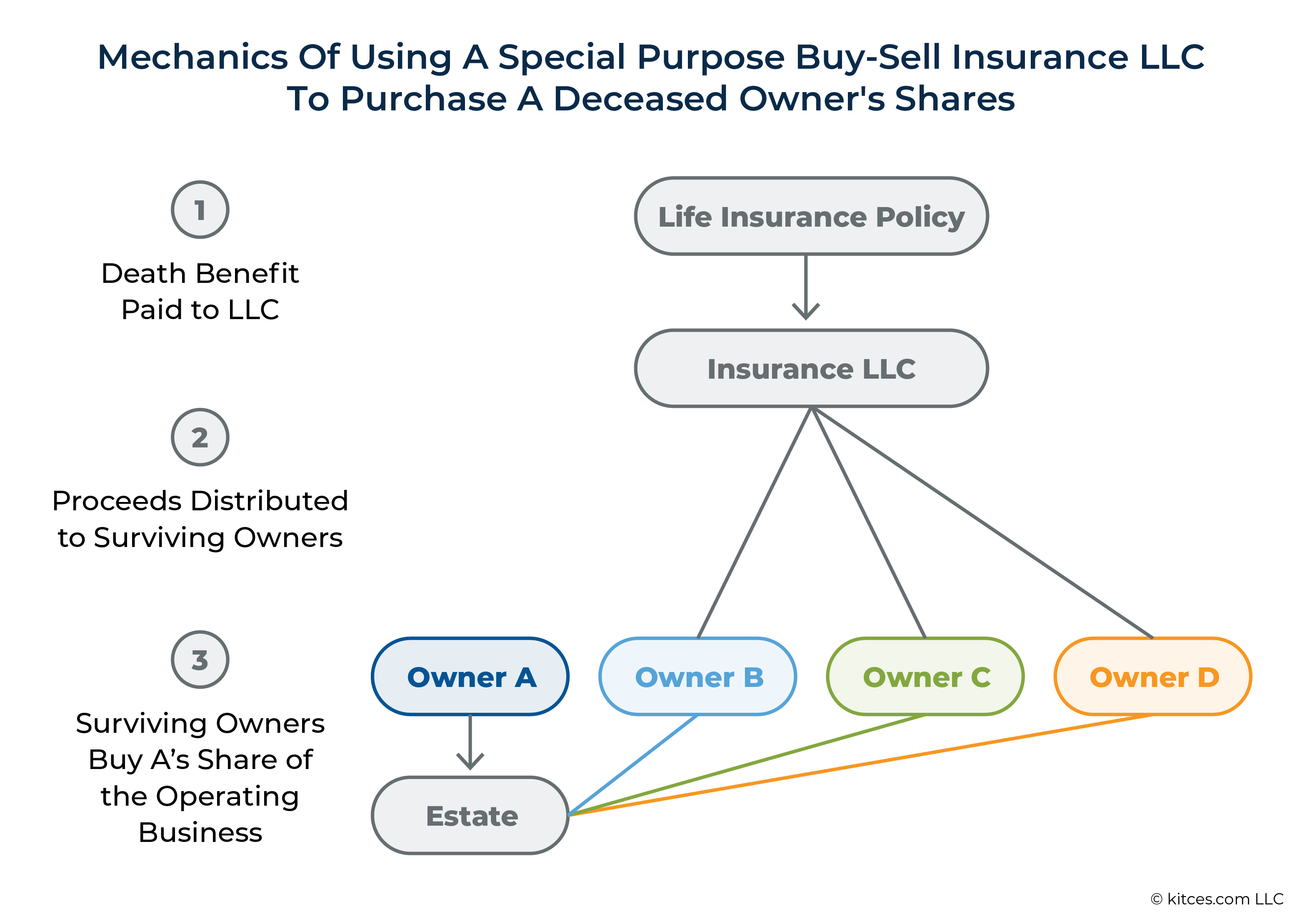

When an owner dies, as shown in the next graphic below, their insurance policy's proceeds are paid to the LLC, and those funds are, in turn, used to purchase the deceased owner's shares in the operating company (as well as their interest in the LLC itself). The LLC's operating agreement can be drafted so that the insurance proceeds are allocated only to the surviving members (and not to the deceased member), which avoids the possibility of the deceased owner needing to include any amount of the insurance proceeds in their taxable estate due to their interest in the LLC.

Notably, the structure of the buy-sell insurance LLC also gives the business owners more tax planning flexibility than a traditional entity-purchase agreement. For example, upon the death of an owner, the life insurance proceeds paid to the LLC could be distributed pro rata to each of the surviving owners, allowing them to purchase the shares from the deceased owner's estate (rather than the operating company itself redeeming the shares, as in a traditional entity-purchase agreement), which would mean that each of the surviving owners would receive a step-up in basis on the shares that they purchase. In that way, an insurance LLC allows business owners to execute, in effect, cross-purchase agreement transactions – since the owners, rather than the operating business, would purchase the shares from the deceased owners' estate – without the need for every owner to own life insurance on every other owner, since the insurance is centralized within the insurance LLC.

Additionally, a business owner using a buy-sell insurance LLC could choose to hold their share of the LLC in a trust such as an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT) or Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (IDGT). That way, upon the death of another owner, rather than the life insurance proceeds being distributed directly to the surviving owner (who subsequently purchases the shares from the deceased owner's estate), the insurance proceeds are instead distributed to the trust – meaning it is the trust that purchases the deceased owner's shares and owns them henceforth, which ensures those shares will remain outside of the surviving owner's estate (and ensures that ownership of an increasing percentage of the company due to the death of one or more of the original owners won't cause estate tax issues for the surviving owners).

Caveats: Will The IRS Also Come For Insurance LLCs?

Despite the potential utility of Insurance Buy-Sell LLCs, it's worth noting that using one isn't necessarily a bulletproof strategy. There are a number of caveats that represent potential risks to business owners using an LLC to hold life insurance policies for the purpose of funding a buy-sell strategy, especially if those policies were originally owned by the operating company, which merit caution and consultation with an attorney and/or accountant with expertise in implementing an insurance LLC strategy.

One big question is whether the IRS will try to use the same economic logic that it successfully used in the Connelly case to argue that insurance proceeds received by an insurance LLC should increase the value of the deceased LLC member's ownership share for estate tax purposes. Even though, as noted above, an LLC agreement can structure its members' capital accounts to exclude the value of life insurance proceeds for a deceased member, the IRS can nullify that treatment if it determines that the setup lacks "substantial economic effect", i.e., economic benefits to the LLC and its members beyond tax benefits. In other words, if the IRS determines that the LLC was set up purely as a tax shelter with no other bona fide business purpose or other economic substance, it could recharacterize the LLC's receipt of life insurance proceeds in a way that causes them to be includable in the deceased member's estate – exactly the issue that was supposed to be avoided by using an insurance LLC rather than a traditional entity-purchase agreement in the first place!

Likewise, if the IRS determines that the insurance LLC has no valid business purpose, that could also cause it to disregard the LLC's partnership treatment and treat the life insurance policy as being owned by the individual members. And because the partnership is needed for the insurance proceeds to qualify for income tax-free treatment under the transfer-for-value rules as noted earlier, the IRS ruling to disregard the partnership would cause the insurance policy's proceeds to become taxable to all of the business's owners in proportion to their ownership interests in the LLC.

In the wake of the Connelly ruling, it's very possible that the IRS will start to scrutinize special purpose buy-sell insurance LLCs more closely and to challenge LLCs that it determines don't have a valid business purpose other than tax avoidance. Notably, in the past, the IRS has approved (via Private Letter Rulings) the structure of insurance LLCs where "engaging in the purchase and acquisition of life insurance policies on the lives of the partners" was considered a valid business purpose; however, it has since indicated that it will no longer issue rulings on whether the insurance LLC will be treated as a valid partnership or whether the insurance policy will be exempt from the transfer-for-value rules. Which makes it all the more difficult for business owners to have any certainty about whether an insurance LLC will actually accomplish their goals, or if it will create a worse situation than the status quo of simply having the original operating business own the policies.

At a bare minimum, then, implementing a buy-sell insurance LLC strategy requires careful planning, drafting, and adherence to the LLC's operating agreement. For instance, the agreement may need to specify how the capital accounts of each member are calculated and how a deceased member's share of the LLC is determined for estate tax purposes. Then, the LLC will need to keep accurate books and records to show that each member's capital account adheres to the methods laid out in the LLC agreement. The LLC also may need to own some assets other than the insurance policies (e.g., business real estate or property that could be leased back to the operating company for rental income, which could be used to pay the policies' premiums) in order to demonstrate a valid business purpose.

Ultimately, the decision to move forward with an insurance LLC comes down to whether the additional complexity and risk are worth it to avoid the inclusion of life insurance proceeds in the value of the business for estate tax purposes. Additionally, there needs to be consideration of other alternatives like switching to a cross-purchase agreement – which, while being expensive and cumbersome to start up (as it would effectively require restarting the succession plan from scratch), may not actually be that much more expensive than an insurance LLC, which itself adds an additional layer of expense and management to the planning process (since there will be fees involved in drafting and filing the LLC formation documents, amending the existing buy-sell agreement, filing partnership tax returns annually, and paying the LLC's third-party manager). But for business owners who are willing to accept the risk and can carefully adhere to the recordkeeping and compliance requirements for an insurance LLC, it could be the best path forward in navigating a tricky tax landscape in the wake of the Connelly ruling.

For the relatively few business owners whose estates exceed the Federal estate tax threshold and who have entity-purchase buy-sell agreements with life insurance proceeds that would be paid directly to the business to redeem a deceased owner's shares, the decision in Connelly v. IRS is an obvious call to action to review the plans that were in place and, if necessary, to find some other arrangement like the life insurance buy-sell LLC that wouldn't force them to include the value of life insurance proceeds in their taxable estate.

But for all business owners, the Connelly case serves as a reminder of the importance of reviewing succession planning strategies – including buy-sell agreements and any life insurance used to fund them – to ensure they continue to meet the business owners' goals and needs. Just as many businesses need to be fast-changing and dynamic in order to survive, so too do succession planning strategies need to adapt when the circumstances of the owners, the business, and the legal or regulatory environment dictate changes.

Leave a Reply