Executive Summary

In today’s increasingly competitive landscape for advisory firms, financial advisors are looking for any way they can to differentiate. Whether it’s their experience and credentials, specialization or depth of services, or simply the sheer size of the firm, based on its assets under management. After all, the reality is that – justified or not – a sizable reported AUM does imply a certain level of credibility and represents a form of social proof (the firm “must” be good, or it wouldn’t have gotten so much AUM, right!?).

As a result of this trend, though, advisory firms are increasingly pushing the line in counting – or potentially, over-counting – their stated assets under management. Which is important, because not only is overstating AUM a potential form of fraudulent advertising, but the SEC has very explicit rules to determine what should be counted as AUM (or not) for regulatory purposes.

Specifically, the SEC states in its directions for Form ADV Part 1 that regulatory AUM should only include securities portfolios for which the advisor provides continuous and regular supervisory or management services. And while most financial advisors today are regularly working with clients regarding their investment securities, not all advisors are necessarily providing “continuous and regular” services on their client accounts. In fact, if the advisor doesn’t have direct authority to implement client trades (either with discretion or after the client accepts the advisor’s recommendation), it’s virtually impossible to include the account as part of regulatory AUM.

The greater challenge, though, is that the increasingly common offering of comprehensive financial planning services – where advisors provide holistic financial planning advice on all of a client’s net worth – does not mean the advisor can claim all of those assets as regulatory AUM. In fact, most of the time the advisor should not include outside 401(k) plans and other non-managed assets that were advised upon as part of the financial plan, nor the value of brokerage accounts holding mutual funds and various types of annuities (unless the advisor truly provide ongoing management services), nor TAMP or SMA assets (unless the advisor retains the discretionary right to hire/fire the manager and reallocate to another one). In fact, even having discretion over an account doesn’t automatically ensure it being counted as regulatory AUM, particularly if it’s a passive buy-and-hold account, unless the advisor can actually substantiate that monitoring and due diligence is occurring outside of any ad-hoc or periodic client review meetings!

Fortunately, for advisors who want to report some number representing the total scope of their advice – including the amount of assets that don’t count as regulatory AUM – it is permissible to report on Assets Under Advisement (AUA) in the advisor’s marketing and in Part 2 of Form ADV, as long as the advisor can document and substantiate the calculation process. But the fact that it’s permissible to report both AUM and also a (typically large) AUA amount doesn’t change the fact that, when reporting regulatory AUM itself, it’s crucial to report the right number!

The Importance Of Regulatory Assets Under Management

It is a standard of the media, especially trade publications, to cite an advisory firm’s assets under management (AUM) when interviewing the advisor. In some cases, the size of the firm simply helps to provide context to the advisor’s comments (e.g., was he/she speaking on behalf of a “large” firm or a “small” one?). In other scenarios, though, the advisor’s AUM is used as an implied marker of credibility – the larger the advisory firm, the more “successful” it must be, and the more valid the comments “must be” of the advisor being interviewed.

The amount of an advisory firm’s assets under management also appears to have an implied credibility factor with consumers. In this regard, the concern for regulators is more substantive. To the extent that consumers might assume that an advisory firm with higher AUM has been more successful, or is a “safer” choice (more continuity), or might offer more services or have more resources because of its size, or simply rely on the firm’s size as “evidence” that it must be a good firm (how else would it have gotten so much AUM if it wasn’t!?), a misrepresentation of the firm’s AUM can amount to fraudulent advertising. Especially since industry benchmarking data suggests that more affluent clients really do tend to choose advisory firms with higher AUM.

And notably, a proper determination of AUM is also important for regulatory purposes, in a world where under SEC Rule 203A-1, “smaller” registered investment advisers with under $100M of AUM must file with state securities regulators, while “larger” firms reporting more than $100M of AUM may register with the SEC (and must register with the SEC within 90 days of reported regulatory AUM exceeding $110M, or must file Form ADV-W and revert back to state registration within 180 days if the firm falls below $90M).

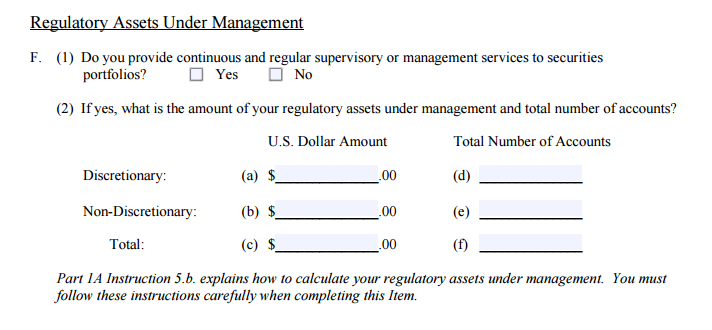

Accordingly, the SEC strictly defines what actually constitutes “Regulatory” Assets Under Management (RAUM) for an advisory firm when it markets itself to the public, and requires these amounts to be reported directly into Item 5.F on Part 1 of the Form ADV filing.

Defining Regulatory Assets Under Management (RAUM)

The SEC defines Regulatory Assets Under Management (RAUM) for the purposes of Item 5.F on Part 1 of Form ADV as “securities portfolios for which you provide continuous and regular supervisory or management services.”

The SEC’s supporting Instructions for Part 1 of Form ADV provide the definitions and explanations of the key phrases: “securities portfolios” and “continuous and regular supervisory or management services”.

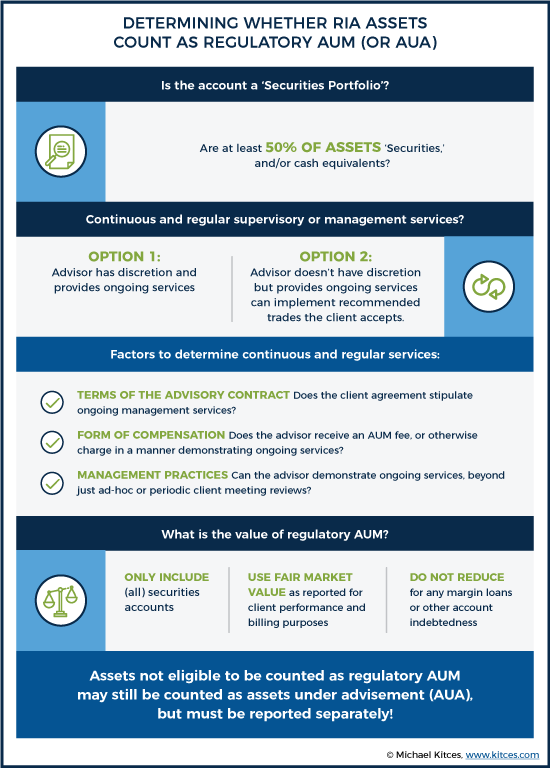

An account is defined as a “securities portfolio” if at least 50% of the total value of the account consists of securities, where a “security” includes any stock, bond, Treasury note, swap or futures contract, or any other investment registered as such. For the purposes of this test, cash and cash equivalents (including bank deposits, CDs, etc.) are also treated as securities, as are all the assets in a private fund (including uncalled capital commitments for the private fund).

For most financial planners and wealth managers operating as an investment adviser, virtually all client accounts will likely be treated as securities portfolios. The more complex requirement, though, is determining whether the advisor provides “continuous and regular supervisory or management services” to that account.

The general criteria to determine whether the advisor is providing continuous and regular supervisory or management services on those securities portfolios are if either:

- a) the advisor has discretionary authority over the account and provides ongoing supervisory or management services with respect to the account; or,

- b) the advisor does not have discretion, but does have an ongoing responsibility to make recommendations of specific securities based on the needs of the client, and if the client accepts the recommendation, the advisor is responsible for arranging or effecting the purchase or sale.

In other words, determining whether the advisor is providing continuous and regular supervisory or management services essentially boils down to: a) does the advisor provide ongoing management or advice; and b) is the advisor responsible for implementing the transaction (either with discretion, or once the client accepts the recommendation). Or as Tom Giachetti of Stark & Stark states even more simply: “If you can’t trade it, you can’t count it [as regulatory AUM]”.

Notably, though, while the ability to effect trades – either with discretion, or the client’s permission to implement a recommendation – is a fairly straightforward litmus test to determine if the advisor would not be able to count the assets as regulatory AUM, the ultimate determination still also relies on whether the advisor provides “continuous and regular” supervisory or management services. Which in practice is often far less clear cut.

To make the determination, the SEC prescribes three primary factors to consider: the terms of the advisory contract, the form of the advisor’s compensation, and the advisor’s actual portfolio management practices.

Terms Of The Advisory Contract. Does the advisor’s agreement with the client actually stipulate that the advisor is responsible for ongoing management services (as opposed to a more limited scope or one-time engagement)?

Form Of Compensation. Being compensated based on assets being managed implicitly suggests that the firm is providing ongoing services with respect to those assets. Although being compensated by AUM fees is not a requirement, the SEC does note that simply charging hourly fees based on time spent with the client (which implies services aren’t ongoing outside the client meeting), or a retainer based on the overall net worth of the client or the assets “covered by” a financial plan (which implies the advisor isn’t being compensated primarily for asset management), suggests that the advisor’s focus is not on providing continuous and regular supervisory or management services.

Management Practices. To what extent does the advisor’s actual investment process demonstrate that continuous and regular management services are being provided? Clearly, ongoing trading activity would demonstrate ongoing services. Notably, infrequent trading (e.g., a buy-and-hold strategy) does not automatically mean the advisor isn’t providing continuous and regular services, but it does create an additional burden on the advisor to substantiate what, exactly, is being done on an ongoing basis to substantiate that the assets are actually being supervised or managed.

In fact, the SEC explicitly notes that advisors who make an initial asset allocation recommendation, but don’t do continuous and regular monitoring and help implement reallocation trades, would not be providing continuous and regular services (and thus cannot count those client assets as regulatory AUM). Nor would just providing trading recommendations (e.g., what to buy or sell) without any ongoing management responsibilities, or providing impersonal (not-client-specific) investment advice (e.g., via a market newsletter).

Similarly, the SEC states that merely providing advice on an intermittent basis (e.g., upon client request), or on a standard periodic basis (e.g., quarterly or annual meetings to review the account and make adjustments), are not continuous and regular management services. In other words, even meeting with clients “regularly” on a quarterly basis is not continuous and regular asset management; the advisor must also substantiate that due diligence monitoring and other management services are occurring between the quarterly (or less frequent) meetings as well!

On the other hand, it’s also notable that continuous and regular services can be in a supervisory capacity, and not necessarily a hands-on management role. Thus, having discretionary authority to allocate client assets amongst various mutual funds (which in turn have their own managers) may still allow those assets to be treated as regulatory AUM. Similarly, using third-party managers (e.g., via a TAMP or SMA) and operating as a “manager of managers” is also permitted, but only if the advisor retains discretionary authority to hire and fire those managers and/or to reallocate assets amongst them. (If the advisor doesn’t have discretion to hire and fire the third-party managers without the client’s permission, or to reallocate amongst the third-party managers, though, it is not regulatory AUM!)

Calculating The Total Amount Of Regulatory AUM

Once it is affirmed that the advisor is providing continuous and regular supervisory or management services, and the client accounts do constitute “securities portfolios”, it’s time to actually add up the amount of assets under management.

In this context, the advisor should still only include accounts (or portions thereof) for which the advisor actually provides continuous and regular supervisory or management services – i.e., even if the advisor meets the rest of the requirements, the holdings of a securities portfolio that aren’t continuously and regularly monitored or supervised aren’t included in the AUM calculation. On the other hand, as long as they’re otherwise managed, advisors should include any family accounts, proprietary accounts, or even accounts for which the advisor is not directly compensated (e.g., “house” accounts).

When reporting the calculated amount of regulatory AUM on Form ADV (or for filing the annual ADV update or an “other than annual” ADV amendment), assets should be reported based on their fair market value, using values calculated within 90 days prior to the filing of the ADV (or update). Fortunately, while the SEC does provide substantial latitude to the advisor in determining what is a “reasonable” estimate of value – which is straightforward for market-traded securities, but can be more challenging for infrequently traded or illiquid assets. However, the SEC does expect that the advisor is consistent in using the same values for AUM calculation purposes that are used to report values to clients (e.g., in quarterly or annual portfolio statements) and when calculating the advisor’s own fees.

Notably, when determining total AUM, the SEC directs investment advisers to calculate regulatory assets under management without reduced the value by any indebtedness associated with the account (e.g., margin loans or other securities-based loans). In other words, regulatory AUM is calculated based on the advisor’s gross assets under management (including securities purchased with borrowed amounts), not the net value of the accounts! (From a regulatory perspective, the requirement to use gross assets, and including such a wide range of assets, was intended to prevent advisors from excluding assets to try to stay below the thresholds for registration and reporting systematic risk requirements after Dodd-Frank.)

Common Mistakes And Pitfalls For RIAs Calculating Regulatory AUM

With recent high-profile fraud cases like Dawn Bennett, the SEC appears to be increasingly scrutinizing whether investment advisers are accurately stating their AUM. And notably, the whole purpose of determining regulatory AUM isn’t just to report it on Form ADV, but that “regulatory” AUM is the only AUM that an advisor should claim as such. Whether that’s in Part 1 of Form ADV where asked, or the matching amount in the ADV Part 2 brochure, or on the financial advisor’s website or other marketing materials.

But in practice, it appears that the most common problems are not the “straightforward” scenarios of deliberate fraud – where an RIA knowingly overstates its regulatory AUM. Instead, it’s situations where the advisor unwittingly overstates AUM by failing to properly exclude assets/accounts that don’t actually meet the requirements for inclusion as regulatory AUM.

For instance, common mistakes and pitfalls when determining AUM includes counting:

- All investments in all accounts, without segregating out non-managed accounts that might happen to be included in the advisor’s portfolio accounting software (but aren’t actually accounts receiving continuous and regular management services from the advisor, and therefore shouldn’t be counted).

- All investments in a hybrid advisor’s book of business, without recognizing that the brokerage assets, for which the advisor doesn’t have an advisory agreement nor discretion, should not be counted as regulatory AUM. In other words, a hybrid advisor that has $20M in C-share mutual funds in a brokerage account (and receives a 1% trail) who also has $30M in advisory accounts under a corporate RIA should only be reporting $30M in regulatory AUM, and not $50M. Generally, if there is no discretion with the client, and no ongoing advisory agreement to substantiate continuous and regular services with the client (which typically isn’t the case for brokerage accounts), the mutual funds, variable annuities, etc., probably should not be counted as (regulatory) AUM!

- Fixed annuities, along with fixed-indexed annuities, which are not counted as securities at all, and therefore should not be included when discussing the advisor’s regulatory AUM.

- TAMP or SMA assets where the advisor may have recommended the third-party manager, and may be paid an AUM fee, and may have implemented a “discretionary” account because the third-party manager has discretion… but the advisor doesn’t have discretion to hire/fire/change third-party managers, which renders the accounts/assets ineligible to be counted as regulatory AUM.

- The value of “outside” 401(k) plans on which the advisor provides investment recommendations, but doesn’t actually provide ongoing and regular management services because the advisor doesn’t actually have the authority or capability to effect trades (because the advisor doesn’t control or have access to the account). Notably, if the advisor has login credentials to the client’s account, and can effect trades, the assets may be included in regulatory AUM… but having access to client login names and passwords for third-party accounts could trigger custody under Rule 206(4)-2!

- Assets for which the advisor is a consultant – e.g., in the case of working with institutional clients as a plan consultant or advisor to the investment committee – but where the advisor doesn’t have discretion and/or cannot implement the trades. Just because the advisor gives advice regarding those assets, doesn’t mean they can be claimed as assets under management!

- Otherwise discretionary assets that are bought and held, and only reviewed when clients come in for periodic review meetings. While the definition of regulatory AUM is not limited to “just” active managers, if a passive advisor wants to substantiate regulatory AUM, it’s necessary to share that there is an ongoing supervisory due diligence process to monitor client accounts and the underlying investments all year long, not just at review meetings!

- Assets for which advice is given on an ad-hoc basis as part of an hourly or financial planning retainer agreement. Notably, the mere fact that advice is being charged for on an hourly or retainer basis does not automatically disqualify the assets from being considered as regulatory AUM. But if the advisor is only charging for client-facing time, and no other time, it implicitly demonstrates that the advisor is not engaging in continuous and regular supervisory or management services. And in the case of a retainer-based advisor, it’s not enough to just show ongoing fees and regular client meetings; again, as in the case of a passive advisor, it’s also necessary to show what monitoring, supervisory, and/or management services are being provided on an ongoing basis as well.

Regulatory AUM Vs Financial Planning Assets Under Advisement (AUA)

In recent years, the growth of financial planning has increasingly broadened the scope of assets on which financial advisors provide advice. As a result, it’s now increasingly common for advisors to provide advice about the client’s entire net worth, and all of his/her assets (and liabilities), including both the accounts that the advisor manages, and those the advisor merely “advises” (and financial plans) upon.

Nonetheless, assets on which the advisor merely advises and includes in the financial plan are not assets under management for regulatory purposes – which means they should not be claimed as assets under management at all.

As an alternative, though, a growing number of advisory firms are also claiming “assets under advisement” – or AUA – which includes the value of all assets that are touched by the advisor/client relationship. This would include most of the various assets discussed earlier that are part of the client’s household net worth but not eligible for being counted as regulatory AUM. In the broadest of situations, AUA might simply include the total net worth of all clients for which the financial advisor does financial planning or otherwise provides advice.

Fortunately, the SEC does permit advisors to describe, in Item 4 of the Part 2 Form ADV brochure, their assets under advisement. (The SEC never directly uses the term “assets under advisement”, but it does permit advisors to compute the “client assets managed” in a different manner than “regulatory assets under management”.) However, if the advisory firm does report AUA (or some other alternative approach to calculating “managed” assets, it should be done separately from (i.e., in addition to) regulatory AUM, and the RIA should keep documentation describing the methodology used to calculate AUA and substantiating the total amount reported. (Which in turn should be kept for 5 years, as part of the general requirement for retention of books and records under Rule 204-2.)

Of course, if more and more advisory firms begin to report their AUA in addition to their AUM – which seems likely, given both the temptation to report what will typically be a larger asset AUA amount for marketing purposes, and the shift of financial advisors to more holistic financial planning where advice really is given on a wider range of assets – it seems only a matter of time before regulators intervene to more strictly define the calculation of Assets Under Advisement (AUA) as well. For the time being, though, the SEC (and state securities regulators) are providing more latitude to RIAs to calculate and report their own AUA (as long as the methodology is disclosed and the amount can still be substantiated). But even with AUA being permitted, it’s still crucial for financial advisors to actually report it as such, and not overstate their regulatory AUM instead!

Special thanks to Chris Stanley of Beach Street Legal, for his guidance regarding this compliance topic!

So what do you think? Does AUM serve as a form of "social proof" among prospective clients? Have you run into any common mistakes advisors make when calculating AUM or AUA? Do you report both? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!