Executive Summary

Generally speaking, business owners have at their disposal two common accounting methods allowed by the IRS. The first, and more complex, is the accrual method, in which businesses recognize income when the business has performed its service or delivered its goods, and expenses after everything has occurred that would require an expense to be paid. Neither of which require the buyer to actually pay the seller.

Conversely, the other, and far more common method for small business owners, of accounting is the cash basis method, generally does require the exchange of funds, and typically is not dependent upon the preceding (or subsequent) delivery of good or rendering of service.

While historically business transactions were relatively straightforward and direct, the advent of debit cards, credit cards, and other means of electronic payment means that buyers and sellers now affect their transactions in some form of payment other than cash.

Fortunately, though, the cash basis method allows for more than just the transfer of actual cash. For instance, a payor’s expense recognition for paper checks that are mailed depends not on the date written on the check itself, but on the date of the postmark… which can be meaningful if that occurs at the end of the year. Conversely, payees don’t wait until the funds hit their checking account to record income, but rather, can recognize income once the check is received.

Meanwhile, credit card payments have their own subtle differences from cash or checks, in that payee’s must wait until the money from the payment is actually credited by the payment processor to their account, whereas the payor recognizes the expense as soon as the charge is made, rather than when they (eventually) pay the credit card bill.

All of this raises some potentially useful strategies to affect positive tax outcomes (recognizing, of course, the oxymoron inherent in that phrase). For instance, business owners can reduce taxable income in a given year by waiting to send out invoiced for goods delivered or services rendered, thus pushing out income into the following year. Alternately, businesses looking to increase current-year deductions could prepay certain expenses, like insurance, and using something called the “12-Month Rule,” a substantial amount of those (and other) expenses can be pulled into the current year in order to stack deductions.

Other useful strategies include taking advantage of Bonus Depreciation – which allows for accelerated depreciation of certain assets, and (after the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) gives businesses the ability to deduct 100% (!) of the purchase price of used property that is “new” to the business – and the Section 179 expensing election, which is also a way to accelerate depreciation and was enhanced by the TCJA.

The key point, simply, is to recognize that there are several strategies that advisors can help business owners take advantage of, and create, some real hard-dollar savings. And, while some of these strategies may be relatively straightforward, they can still have a significant impact on a business owner’s tax liability.

In the early days of a business, there are often what seems like a never-ending list of decisions that must be made. One of those key decisions is the accounting method that will be adopted by the business.

Simply put, an accounting method is just a standardized way of determining when revenues and expenses should be reported as income and deductions. Under IRC Section 446, taxpayers are generally able to select which method of accounting they will use to calculate their taxable income, “so long as the business regularly uses that method in keeping its books, and that the method clearly reflects the income of the business.”

In general, there are two primary methods of business accounting: the “cash receipts and disbursement method” (better known as “cash basis accounting”), and the accrual method. In limited scenarios, other methods, or a combination of cash basis and accrual accounting may be available. And once a method of accounting is chosen (when the business files its first income tax return), per the requirement that the business “regularly uses that method in keeping its books,” the business must generally continue using the same method of accounting unless it applies for, and receives, permission from the IRS to make a change.

Determining Income And Expenses Using The Accrual Method Of Accounting

IRC Section 451 outlines the “basic” rules for accrual method accounting. And under IRC Section 451(b)(1)(C), when using the accrual method of accounting, a business should generally include income in its taxable income once “all the events have occurred which fix the right to receive such income” – essentially meaning the business has performed the services/provided the goods for which they were/will be paid and has earned the income – such that “the amount of such income can be determined with reasonable accuracy.”

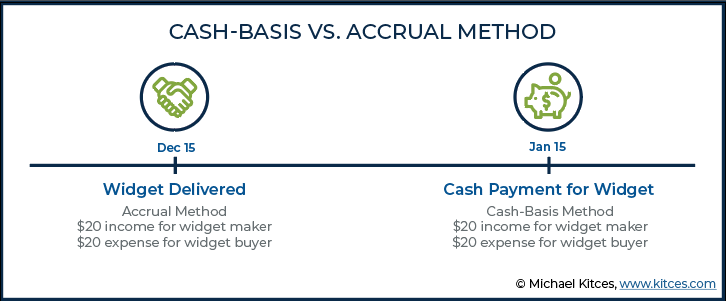

Notably, when using the accrual method of accounting, no cash or other payment must actually be received by a business for it to be required to report taxable income. Rather, the business just needs to be entitled to that income (i.e., have “earned” it). For example, suppose that a widget maker delivers a new widget to a customer, who agreed to purchase the widget for $20. If the widget maker uses the accrual method of accounting, then the moment the widget is delivered, and the sale is completed, the widget maker should record $20 of income, regardless of whether the company has actually received the $20 payment for the widget.

Similarly, under IRC Section 461, expenses (deductions) should be generally be included in the calculation of taxable income once all events have occurred that require the expense to be paid, and the amount of the expense can be reasonably calculated. For instance, suppose our widget maker engages in a six-month consulting agreement with another firm at a rate of $1,000 per month (for a total of $6,000). If after month one, the widget maker pays the full six-month, $6,000 consulting contract invoice, they will still only “book,” or record, one month’s expense of $1,000 because only 1 month of services have actually occurred (and the remaining $5,000 would be considered a “prepaid expense” asset of the firm, to be depleted as the consultant earns the remaining payments over time).

Determining Income And Expenses Using The Cash Basis Method Of Accounting

By contrast to the accrual method of accounting, the cash basis method is generally much simpler, and far more intuitive. Thus, it’s not surprising that the cash basis method is the most common method of accounting for small businesses, like sole-proprietorships, S corporations, partnerships, and LLCs.

And thanks to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and its easing of certain rules that prevented some small-ish C corporations (and partnerships with one or more C corporation partners) from using the cash basis method, it’s likely more of those businesses will begin to use the cash basis method as well. Notably, prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, IRC Section 448 prevented C corporations with annual average gross receipts of $5 million or more for the three-prior-year taxable period from using the cash basis method. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, however, increased this amount to $25 million.

You might think of the cash basis accounting method of accounting as the “Jerry Maguire method” because when trying to determine when to record income and expenses using the cash method, it typically comes down to one thing… “Show me the money!” In essence, when using the cash basis method of accounting, income and expenses are booked when money actually changes hands.

For instance, recall that when using the accrual method, a widget maker records $20 of income once it delivers a new widget to a customer who has agreed to purchase the widget for the same $20, even if the widget maker has not yet received payment. By contrast, when using the cash basis method of accounting, the widget maker only records income if/when payment for that widget has actually been received.

If, for example, the widget maker merely delivers the widget with an invoice, which isn’t paid until 30 days later, the business does not record the $20 of income until payment is received 30 days after delivery (and thus, for 30 days, there is a disparity between the widget maker’s income under the accrual method and under the cash basis method).

Similarly, recall that when using the accrual method, when a widget maker engages in a six-month consulting agreement at a rate of $1,000 per month (for a total of $6,000), the widget maker can only record the expense of that agreement as services are performed (i.e., $1,000 per month). By contrast, if the widget maker pays the full $6,000 consulting contract invoice in one fell swoop, they can generally record (i.e., deduct) the full $6,000 expense at that time.

Reporting Various Types Of Payments And Receipts When Using The Cash Basis Method Of Accounting

While some businesses are more “cash heavy” than others, today the majority of transactions are made using some sort of instrument other than actual cash, including debit cards, credit cards, and other electronic payment systems. In fact, according to a report from the Federal Reserve, as of 2015, just 32% of transactions were being made using cash, down nearly 20% from just three years prior.

Accordingly, though, the cash method of accounting provides for more than just actual hard-dollar cash payment transactions. As a result, it’s necessary to understand how to determine when a “cash” payment has happened for a cash basis taxpayer (whether as a payor or a payee) even when actual cash isn’t being used!

Accounting For Actual Cash Transactions Using The Cash Basis Method

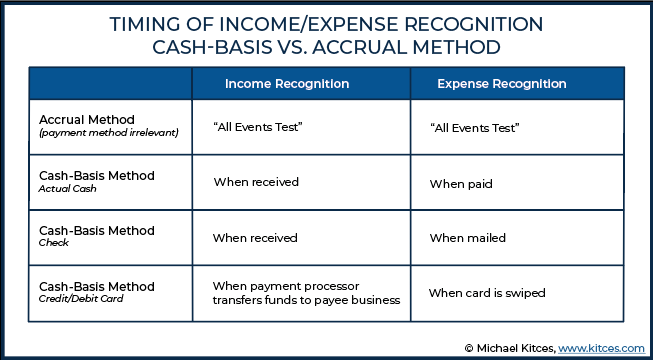

Not surprisingly, accounting for actual cash transactions using the cash basis method of accounting is fairly straightforward. In general, the moment cash is received by a payee, the payee will record the amount as income. Similarly, a payor using the cash basis method will generally record payments made in cash as an expense as soon as the actual cash changes hands.

Furthermore, cash transactions are generally made in person, where payment by the buyer and receipt of payment by the seller, happen simultaneously (for obvious reasons, you don’t exactly see many businesses Fed-Exing around palates of cash?). Thus, a seller’s income and a buyer’s expense generally happen at the same moment (simply identified by the moment of exchange).

Accounting For Check Transactions Using The Cash Basis Method

Today, checks account for fewer transactions than cash, debit card, credit card or other electronic payments. Nevertheless, there are still a significant number of transactions that involve checks. And perhaps not surprisingly, the older an individual is, the more likely they are to use a check as a form of payment.

Much like cash, checks are often presented in person. And in such situations, the accounting treatment is generally the same as cash. A cash basis payee would have income upon receiving the check, and a cash basis payor would have an expense when the check is handed over.

It’s not uncommon, however, for checks to be mailed from one business to another, and in such situations, the expense of the payor and the income of the payee no longer occur at the same time.

For the payor, the expense can be “booked” when the check is sent out. Which, notably, is not always the same day as the check is dated, and backdating a check does not allow you to claim the expense as a deduction in the current year if the check was not also mailed out by the end of the year.

On the other side of the transaction, the cash-basis-payee business does not record the income attributable to the check until the check is actually received. Note, however, that the payee does not have to actually deposit or cash the check for it to be considered income. Instead, under the Doctrine of Constructive Receipt and Treasury Regulation 1.451-2, you must generally include “amounts credited to your account, set apart for you, or otherwise made available so that you draw upon it at any time, or so that you could have drawn upon it during the taxable year if notice of intention to withdraw had been given.” A check that has been received would meet the “set apart for” test and thus, would be considered income even if not cashed.

Example: #1: Frank’s Franks is a cash basis business that supplies local restaurants with artisanal frankfurters. On December 26, 2018, Frank’s Franks makes a delivery of frankfurters to Meet Me For Meat, another local restaurant. Included in the delivery was an invoice for $2,500.

In an effort to ensure the purchase can be included as a 2018 expense, on December 27, 2018, Meet Me For Meat’s CFO draws up a check for $2,500, payable to Frank’s Franks. The following day (December 28, 2018), the check is signed and mailed out to Frank’s Franks. Thus, as a cash basis taxpayer, Meet Me For Meat has met the requirements to claim the $2,500 as a 2018 expense, regardless of when the check gets cashed.

Now, suppose that the local postal service is operating smoothly, and that on December 31, 2018, Frank’s Franks receives the check of $2,500. Frank’s must include the $2,500 payment in its 2018 taxable income, even if they don’t deposit the check until early January 2019.

If, on the other hand, the local postal service is backed up with holiday packages and the check does not arrive until January 2, 2019, Frank’s Franks must record the income as 2019 income. Note that there is no choice in the matter. The check is income to Frank’s Franks when they receive it. Period. End of story.

A common question of cash-basis-method business owners when it comes to year-end payments is, “How is the IRS going to know exactly which day I send out or receive a check?”

Candidly, the answer is often, “They won’t,” but that doesn’t mean that business owners can do what they want. The rules are still the rules, and in practice, the post office generally stamps an envelope with a date when it is processed for mailing (which makes it very difficult for the payor to be “fuzzy” on the date!). Though notably, because it’s not always clear when an envelope is received, that ambiguity may work to the advantage of business owners looking to push income to the following year (by saying that the income was not received until that following year, though it would still be fraudulent to make that statement if the check really was received before the end of the year).

In situations where the payment of an expense would have a material impact on a business owner’s taxable income, it is often best to mail out checks using certified mail, or some sort of private delivery service (e.g., UPS, Fed-Ex, DHL) that would provide proof of mailing date. Similarly, business owners who wish to have evidence of the delivery date of when checks were received (if only to prove payment really was received after the close of the year) may wish to digitally capture images of incoming mail daily, similar to United States Postal Service’s Informed Delivery program (which is currently only available for residential deliveries).

Accounting For Credit Card Transactions Using The Cash Basis Method

Many transactions today are completed using debit and/or credit cards.

Cash basis businesses must include credit card purchases in their income when they receive payment – when the cash from the transaction is deposited by the credit card processor into the business’s bank account. Furthermore, since 2011, Internal Revenue Code Section 6050W has generally required banks and credit card companies to report the gross amount of their payments to businesses on a Form 1099-K. Thus, when it comes to credit card receipts, the IRS usually has a pretty good idea of what a business has generated in credit-card-payment-based income. (In addition, the IRS also has data available on the typical proportion of credit-to-cash receipts by similar businesses. Businesses falling outside these norms should not be surprised to see the IRS seeking further information/confirmation of gross receipts!)

While the receipt of income from credit card transaction follows the basis cash basis rules, there is an exception to the basic cash basis principles when a credit card is used to make a purchase. Business owners using the cash basis method deduct, as an expense, amounts charged to a credit card when the purchase is made… not when they actually use cash (or an equivalent) to pay their credit card bill!

End-Of-Year And Last-Minute Planning Income Tax Planning For Cash Basis Business Owners

In addition to being easier than the accrual method of accounting, the cash basis method offers the added advantage of allowing business owners a greater degree of flexibility by controlling the timing of their year-end expenses by manipulating adjusting when they pay expenses and even, to a certain extent, when they receive income. To that end, cash basis business owners looking to manage their taxable income through the end of the year should consider the following approaches:

Strategy #1: Delay Getting Paid By Delaying Your Invoices

In general, once a business has provided the services or goods for which payment is required, they want to get that money as quickly as possible. That process typically includes sending out invoices as soon as possible.

But if you’re a business using the cash basis method of accounting, and if you’re trying to minimize your taxable income for the year, that may not be the best approach. In fact, you might want to consider intentionally delaying sending out your invoices.

Though not always the case, most businesses (and people, in general), will not pay an invoice until they actually receive the invoice. Thus, if the end of the year is approaching and it’s determined that “pushing” out income into the following year is advisable, then it’s often worth considering delaying the sending of invoices out to customers until late December of the year in question (such that they won’t realistically be paid until early January), or even to early the following year (just to ensure they’re not paid “too quickly” in late December). Doing so will (naturally) delay the receipt of most payments attributable to those invoices – and the corresponding income – until the following year, helping to minimize the current year’s tax liability by delaying when the income itself must be reported for another year.

A quick word of warning about this strategy... the old saying “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” applies here. A dollar of income that has been taxed is always better than 100% of nothing. So if you’re dealing with a customer with a sketchy payment history, or who takes forever to pay anyway, or who you just don’t have confidence will pay when you finally do “get around” to sending your invoice, it’s probably best to get your money while you can, even if that means accelerating the income from that payment into the current year!

Strategy #2: Prepay Expenses To Increase Current Year Deductions

Another simple (yet highly effective) strategy for cash basis business owners seeking to reduce their taxable business income at the end of the year is to pay as many expenses as possible. As noted above, so long as payment is made/sent out before the end of the year, the payment will count as a current year expense.

This “strategy” can be useful for expenses that have already been incurred, as well as for future expenses that can be reasonably predicted to occur in the near future. A simple example of this would be the payment of an electric bill that is automatically deducted on the 5th of every month from a business’s account. Instead of waiting until January 5th of the next year to have the payment deducted as “normal,” the business might consider making that particular payment prior to the end of the year so as to utilize the amount of the payment as a current year deduction.

Common recurring expenses to consider accelerating into the current year include:

- Contract labor (e.g., payments to independent contractors)

- Wages (to employees before the end of the year)

- Utility bills

- Insurance premiums

- Rental payments (if the rental agreement is short-term or is near completion)

- State and local income taxes and fees (though typically, small, cash-basis businesses are pass-through entities which don’t have large entity-level state and local tax bills)

- Office supplies

- Professional subscriptions, membership fees, association dues, etc.

- Software licenses

(Notably, deductions for purchasing assets, or “stuff” in general, is subject to different rules, as discussed in a later section below.)

What if there’s a need to reduce taxable income via additional expenses, but no cash on hand to actually pay those expenses? No problem! Recall that payments made via credit card are considered paid at the time the credit card is swiped. Thus, a cash basis business owner can use their credit card to make purchases prior to the end of the year – which will be eligible for a current-year deduction – and then pay off the credit card balance in the following year, once the cash is available!

Of course, in such cases, business owners should be mindful of any potential interest that may accrue as a result of not being able to pay the credit card balance off in full. Given the high interest rates associated with many credit cards, a balance carried over for even a few months could run up interest charges that would more than offset any tax benefits generated from accelerating purchases into the current year.

Using The 12-Month Rule To Super-Charge Prepayments Of Expenses

Treasury Regulation Section 1.263(a)-4(f) allows business owners using the cash basis method of accounting to take this even further by allowing the business to deduct most prepayments of expenses so long as any right or benefit attributable to the expense does not extend beyond the earlier of:

- One year from the time the benefit is first realized; or

- The end of the taxable year following the taxable year in which the payment is made.

This benefit is commonly known as the “12-Month Rule” and makes it possible to not only deduct the coming month’s insurance premiums as a business expense by prepaying it by the end of the current year, but potentially the entire next year’s worth of insurance premiums by prepaying before the end of the current year (assuming the business has the available cash, of course).

More generally, the 12-Month Rule makes it feasible for business owners using the cash method of accounting to potentially accelerate the payment of a substantial amount of 2019 expenses into 2018 in order to “write them off” as 2018 deductions.

Example #2: On September 1, 2018, Frank’s Franks purchased general business liability insurance for $12,000 for the coming year. As of December 15, 2018, the company has made four monthly payments of $1,000. Thus, there is $8,000 of unpaid insurance premiums that will still be due on the contract.

If Frank’s Franks wanted to take additional steps to reduce its taxable income for the year, it could make a payment for the remaining $8,000 of business insurance premiums by the end of the current year to cover the remaining 8 months of payments for the next year.

Of course, like just about everything in the Tax Code, there are always “gotchas” that business owners need to be aware of. For instance, suppose that a business’s rental agreement extends from July 1, 2018, through June 30, 2020. Prepaying 2019’s rental expenses would not increase the business’s 2018 deductible expenses since the benefit of the lease extends beyond the end of 2019. So with that in mind, prior to prepaying any expenses, it’s generally not a bad idea for business owners to double-check with their tax professionals to make sure payments of prepaid expenses will indeed be deductible!

Strategy #3: Make Use Of Special Deduct-As-Expenses Elections

In general, the Internal Revenue Code does not treat the purchase of an asset as an expense of a business. Rather, the purchase of an asset merely changes the nature of a business’s existing assets. For example, if a business purchases a computer for $5,000 with $5,000 of cash in its bank account, the business would generally record the transaction by reducing its cash assets by $5,000 while correspondingly increasing its equipment assets by $5,000… resulting in a net change of $0.

Of course, anyone who has ever purchased a computer (or a car, or really, most assets other than real estate) knows that assets typically do not hold their value over time; instead, they depreciate. To account for this, businesses are generally able to claim a depreciation deduction, which does count as a deduction that reduces taxable income.

To avoid abuse, standard schedules exist which generally dictate how quickly any particular asset can be depreciated based on its typical lifetime (which can range from 3 years for things like tractor units for over-the-road use and racehorses over the age of 2 when placed in service (yes… seriously!) to 39 years for certain types of real estate). Which means the deductions for buying an asset that will depreciate generally can’t be claimed any faster than the IRS-specified time period over which the asset is going to depreciate.

However, there are a number of times when the standard depreciation time period can be accelerated via special tax breaks created by Congress, including:

- Bonus Depreciation: Internal Revenue Code 168(k) allows business owners acquiring tangible personal property with a depreciable period of 20 years or less (as well as other, narrowly defined assets) to accelerate the depreciation of their assets using “Bonus Depreciation.” Qualifying property purchased and placed in service after September 27, 2017, is currently eligible for 100% bonus depreciation… meaning the full purchase amount of the asset can be fully deducted immediately as a current “expense” (even though it’s purchasing an asset)! The Tax Cuts and Job Act made Bonus Depreciation equal to 100% through 2022, after which it will gradually be reduced, until it’s complete elimination for years 2027 and later. Purchases of new property are eligible for the deduction. In addition, a change made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act allows businesses to use Bonus Depreciation for used property that is “new to the business,” so long as that property is not acquired from a related person/entity. Thus, business owners looking to make a sizeable dent in their 2018 taxable income should consider making qualifying purchases prior to the end of 2018 and utilizing the Bonus Depreciation election.

- Section 179 Expensing: Internal Revenue Code Section 179 offers business owners a separate method of accelerating the depreciation deductions associated with an asset. Simply put, the Section 179 expensing election allows certain business owners to deduct the value of certain tangible personal property acquired in the year of purchase. Like Section 168(k) bonus depreciation, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act significantly enhanced this benefit, roughly doubling the amount of property that can be expensed this way to $1 million for 2018. In addition, it also increased the amount of Section 179 property that can be purchased during the year before this benefit begins to be phased out to $2.5 million.

If you’re thinking to yourself, “Boy... these benefits sure seem to be pretty similar,” you’re right… they are! And thanks to the recent changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, including the aforementioned change allowing Bonus Deprecation to be claimed for used-but-new-to-the-business property, they’re more similar than ever.

That said, there are some key differences between the two benefits that can come into play. For instance, Section 179 Expensing is generally used before Bonus Depreciation, but Section 179 Expensing can't result in a loss. Bonus Depreciation, on the other hand, is not limited by taxable income, and thus, a business with a pre-special-depreciation-election loss can create a greater loss by using Bonus Depreciation but will not be eligible to utilize Section 179 Expensing.

Similarly, since the ability to utilize Section 179 Expensing begins to be phased out once eligible property placed in service during the year exceeds $2.5 million, but no similar cap exists for Bonus Depreciation, larger companies with more substantial property purchases are often limited to utilizing only Bonus Depreciation.

It’s important to note that this is merely an overview of the Section 168(k) Bonus Depreciation and Section 179 Expensing elections. A full overview of the rules surrounding these strategies is beyond the scope of this article and, frankly, beyond the scope of where most advisors (who are not also tax professionals) need to go.

The key point, though, is that not only can the purchase of assets often be deducted similar to expenses (even though technically they’re under different rules), but the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act significantly enhanced the ability for business owners to deduct large asset purchases in the year of purchase. Thus, business owners who “need” to make significant reductions in their taxable income before the end of the year should consider accelerating the purchases of any Section 168(k) Bonus Depreciation and/or Section 179 Expensing election eligible property (i.e., certain machinery, office furniture, computers) prior to year-end.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the acceleration of such purchases is worth considering even if a business is short on cash. For instance, the combination of a Section 179 Expensing election along with the financed purchase of qualifying property may actually leave a business owner net-cash-flow-positive! …At least during the year of purchase.

Last-minute tax planning can make a big difference in an individual's tax liability, but such planning is often even more critical for business owners. And thanks to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, year-end tax planning for business owners provides more opportunities than ever. Not to mention that aggressively adding deductions (or deferring income) for some business owners can not only reduce their tax bill directly, but also help reduce the phaseout loss of the new 20% QBI deduction (which otherwise is potentially eliminated for certain types of businesses as income increases, causing a potential loss of as much as almost 50% to Federal taxes alone… to say nothing of the state and local taxes that may also apply!).

Thankfully, though, there are many ways for business owners to take control of their situation and make income and expense decisions (or really, take income and expense actions) that can have a dramatic impact on their tax liability for the year. Cash basis taxpayers, in particular, have the ability to make decisions, even at the proverbial 11th hour, that can allow them to minimize revenues, increase expense deductions, or both. Finally, it’s worth noting that, although these strategies may not have the flair of other, more “advanced” or “dynamic” strategies, for many small business owners, they are of equal or greater importance!