Executive Summary

From February 20th through February 22nd, the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning hosted their second annual Academic Research Colloquium (ARC) for Financial Planning and Related Disciplines in Washington D.C. The event brought together 225 attendees, of which close to 200 were researchers and academic faculty, to share and discuss research relevant to the financial planning profession, as a part of the CFP Board Center’s longer-term goal of establishing itself as the “academic home” for the financial planning profession (and the research that supports it).

In this guest post, Dr. Derek Tharp – a Kitces.com Researcher, and a recent Ph.D. graduate from the financial planning program at Kansas State University – provides a recap of the 2018 CFP Academic Research Colloquium, and highlights a few particular research studies with relevant takeaways for financial planning practitioners.

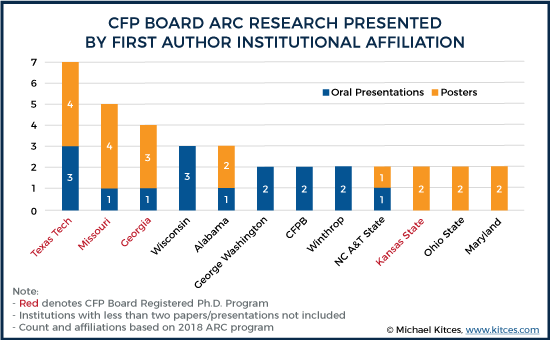

The 2018 CFP Academic Research Colloquium again had a strong showing from some core financial planning academic programs, with scholars from Texas Tech, Missouri, and Georgia serving as lead authors for nearly 25% of all research presentations and poster sessions. Notably, this representation is more diverse than last year, as last year the top four programs accounted for nearly 50% of research presented. Additionally, the colloquium was successful in drawing in scholars from outside of the core financial planning programs, featuring lead authors from a total of 35 different academic institutions, including Harvard, Duke, Georgetown, and Notre Dame.

The colloquium featured a wide range of topics. Some particularly relevant themes for financial planning practitioners ranged from biases that influence financial decision making among both financial advisors and their clients (e.g., how human use of technology to assist with statistical decision-making can help...or not), to issues related to quality of life in retirement (e.g., are retirees happier living near their friends or children?), and racial diversity in the financial services industry, including an examination of the role of empathy in black consumers choice of a financial advisor.

Overall, the second Academic Research Colloquium again brought together a strong mix of academics and practitioners to present and discuss financial planning research. Notable challenges and opportunities for growth in coming years will include the launch of the Center for Financial Planning’s new academic journal (Financial Planning Review), the Center’s push to establish the ARC as the core conference interview location for financial planning faculty positions, and continuing to attract a diverse group of scholars to build and contribute to the financial planning knowledge base. Only time will tell if Center for Financial Planning can be successful in their pursuit of becoming the “academic home” of financial planning research, but the ARC continues to be a strong conference for both financial planning academics, and practitioners interested in financial planning research.

2018 CFP Academic Research Colloquium

From February 20th through February 22nd, the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning hosted their second annual Academic Research Colloquium (ARC) in Washington D.C. The event brought together 225 attendees, of which close to 200 were researchers and faculty, to share and discuss research relevant to the financial planning profession. The CFP Academic Research Colloquium is part of a longer-term goal to establish the CFP Board Center for Financial Planning as the “academic home” for the profession.

Consistent with the 2017 ARC, there was a strong showing among some core academic financial planning programs. Three of the four universities with CFP Board Registered Ph.D. programs—Texas Tech, Missouri, and Georgia—led all universities in terms of papers accepted for an oral or poster presentation (measured by first author institutional affiliation), while the fourth program—Kansas State—was also one of only 12 institutions to have two or more first authors represented.

Overall, institutional representation was more diverse in 2018 compared to the 2017 ARC. In 2017, the top four institutions represented (Georgia, Kansas State, The American College, and Texas Tech) accounted for nearly 50% of all research presented, whereas the top four institutions in 2018 only accounted for about 30% of research presented. Additionally, first authors from a total of 35 academic institutions were featured in 2018 versus 31 in 2017, and the ARC continues to draw researchers from some top-tier universities, including Harvard, Duke, Georgetown, and Notre Dame.

Industry sponsorship was strong again in 2018, with Merrill Lynch serving as the signature sponsor, and $2,500 best paper awards sponsored by TD Ameritrade, Northwestern Mutual, and Merrill Lynch. Specific sessions were sponsored by Wiley and Morgan Stanley, and additional exhibitors or sponsors included Zahn, Kaplan, Keir, National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE), and PlanPlus Global financial planning software.

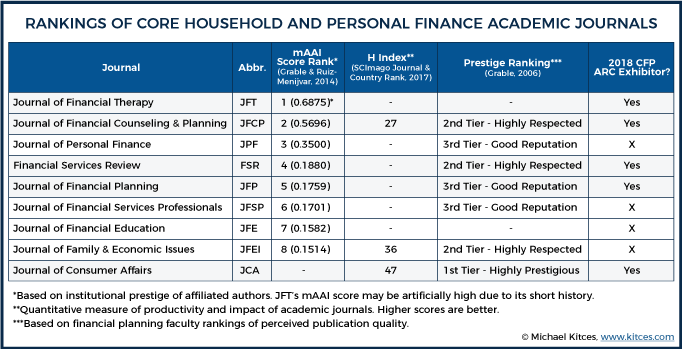

Journal exhibitors again included four of the top five core household and personal finance journals identified by Dr. John Grable and Dr. Jorge Ruiz-Menjivar in a 2014 working paper: Financial Services Review (Academy of Financial Services), Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning (Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education), Journal of Financial Planning (Financial Planning Association), and the Journal of Financial Therapy (Financial Therapy Association). Additionally, although not included among the “core” household and personal finance journals identified by Grable & Ruiz-Menjivar, the Journal of Consumer Affairs (American Council on Consumer Interests) was also an exhibitor, which is one of the highest-ranking journals that will regularly publish content relevant to personal and household finance.

The editors of the Center for Financial Planning’s new journal, Financial Planning Review (FPR), were also in attendance. Dr. Vicki Bogan (SC Johnson College of Business, Cornell University), Dr. Chris Geczy (Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania), Dr. John Grable (University of Georgia), and Dr. Charles Chaffin (CFP Board Center for Financial Planning) led a “Meet the Editors” keynote session in which they shared information about the goals of the new journal (e.g., to establish a research impact factor of “one” in five years [a measure used to assess how often articles within a journal are being cited] and maintain quality metrics sufficient to supporting the ability for faculty in AACSB business schools to earn tenure) and shared a call for papers for an upcoming FinTech special issue (submissions are due 12/31/2018). The first publication date of FPR will be later this year.

Additionally, the Center for Financial Planning announced the release of their new book, Client Psychology, edited by Dr. Charles Chaffin. The book itself contains 19 chapters covering a range of topics related to client psychology—from automated decision aids and financial self-efficacy, to financial counseling and money disorders—all written by academics with some expertise in the topic of the chapter.

The Center for Financial Planning also continued their initiative to become the “academic home” for financial planning by providing space for academic institutions to interview candidates for faculty positions (in an attempt to become “the” conference for first-round interviews, akin to conferences in other academic fields, such as FMA for finance faculty and AEA for economists), as well as space for other academic organizations to hold board meetings.

How Behavioral Biases Influence Financial Decision Making

One important theme of research presented at the 2018 ARC was an examination of several major questions related to biases that influence financial decision-making—including both biases of clients and financial planners themselves.

Using Technology to Improve Statistical Decision Making

Dr. Jason McCarley of Oregon State University gave a presentation titled Interactions between Human and Statistical Decision-Makers: A Review with Implications for Automated Planning.

As many advisors are aware, automating financial decisions can be a great strategy. A “pay yourself first” approach of saving into a retirement account automatically tends to result in higher levels of saving, as we are never tempted to look at the funds in our bank account and spend them first. Additionally, the “Save More Tomorrow” approach which allows individuals to automatically increase future savings in the present, has been shown to substantially increase contributions to employer-sponsored retirement accounts.

And saving is only one area where decisions can be automated. In fact, with the rise of robo-advisors and digital financial planning tools, there is an ever-increasing number of ways in which we can automate various aspects of our financial lives. However, not all automation is the same, and some financial decisions may be better or worse suited to automation.

One important area of decision-making in which there is already a decent amount of research on how technology can assist humans in making statistical decisions.

As Nassim Taleb points out in Fooled by Randomness, we humans struggle with all sorts of statistical thinking. We overstate causality and think the world as more explainable than it is. In other words, we often perceive order in what may be randomness. Additionally, we may particularly fail to identify (or properly assess) legitimate statistical relationships towards the tails of probability distributions, thus why many people are afraid of flying but not driving, even though the latter is a far more dangerous than the former.

As Nassim Taleb points out in Fooled by Randomness, we humans struggle with all sorts of statistical thinking. We overstate causality and think the world as more explainable than it is. In other words, we often perceive order in what may be randomness. Additionally, we may particularly fail to identify (or properly assess) legitimate statistical relationships towards the tails of probability distributions, thus why many people are afraid of flying but not driving, even though the latter is a far more dangerous than the former.

As a result, tools that assist with statistical decision-making could potentially help humans make better financial decisions, so long as we use those tools properly (and other human biases don’t lead to even worse unintended consequences!).

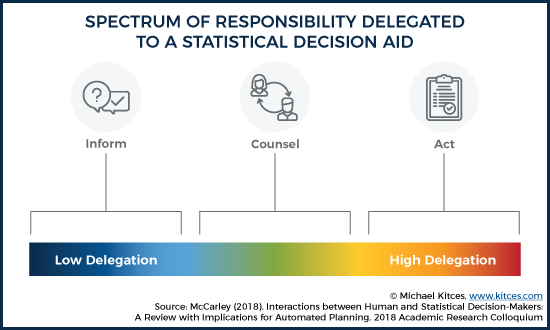

McCarley notes that decision aids exist on a spectrum from low to high responsibility given to the aid. For instance, a decision aid may literally act on our behalf (e.g., cars that automatically brake for you), or a decision aid may simply provide information and allow the human to decide what to do with that information (e.g., financial planning software that uses Monte Carlo analysis).

McCarley also noted that airline pilots are one particular group which historically has made use of decision aids, but perhaps closer aligned to financial planning as a profession, physicians can also make use of algorithms in some narrow contexts. For instance, a team of researchers at Stanford University developed an algorithm which was better at diagnosing pneumonia than expert radiologists. However, computers don’t necessarily do better under all conditions. A recent study led by Hannah Semigran of Harvard University found that physicians outperformed algorithms when given a patient vignette, which better aligns with conditions in which many diagnoses must be made (as often the highly standardized conditions for machine learning to be useful are not feasible). And, in any case, diagnosis is only one part of a physician’s job, and computers currently struggle to determine treatment plans, particularly given the need to look at a patient’s health and views towards medicine holistically, in order to develop an effective treatment plan.

And although we often think of technology in terms of man versus machine, the reality is that often it is the collaboration between man and machine provides the best outcome possible, as is the case in “Cyborg Chess” where human-computer teams are capable of beating both the best computers and the best humans on their own.

But McCarley noted that often the use of decision aids can actually yield disappointing results. This is particularly true because people tend to either misuse or disuse an aid. We may disuse (i.e., under-utilize) an aid for reasons such as overconfidence, ignorance, or lack of good feedback. For instance, an overconfident driver or one who doesn’t understand how truly poor human reaction speed is may be less likely to use an active brake assist (or other autonomous driving assistance) regardless of how effective the actual technology is.

Additionally, we may misuse an aid (i.e., be overly reliant on) for similar behavioral reasons, but particularly when we believe the tool is more effective than it truly is. For instance, despite the huge progress that has been made in developing self-driving vehicles, vehicles available to consumers aren’t fully autonomous yet. However, some drivers have relied too much on the technology, assuming they could sleep behind the wheel or otherwise not pay attention, and have ended up in some avoidable accidents as a result.

Thus, fintech tools which aim to help people automate good financial decision making must do more than simply provide good advice—the tools themselves must be well-designed so that the actual humans using them will do so properly.

For instance, one considerable challenge of Monte Carlo analysis is helping clients understand what the results actually mean. A client who interprets 95% confidence to mean they can retire without any real risk of running out of money (perhaps even enticing them to spend more than they would have without seeing the analysis) may be insufficiently willing to make adjustments should they end up headed down a 1-in-20 path towards "failure". We may not know precisely how to counteract this bias, but it's possible that framing Monte Carlo results as "5% probability of adjustment" and exposing the client to this number over time (e.g., 5% → 25% → 45%), could increase the likelihood of achieving client buy-in to making needed adjustments relative to a one-and-done "95% probability of success" assessment.

McCarley noted some specific ways in which decision aids can be designed for better use. First, the tool should be reasonably effective, as better performance increases human trust in a tool. Second, humans should understand how the aid works, as that helps further build trust in the tool, and may help reduce distrust in a tool when a probabilistic forecast is “wrong” (given that users may be prone to the “wrong side of maybe” fallacy). Finally, tools must be pleasant to use, as any tool that is not will simply not be adopted.

If you would like to read more about topics such as these and their implications for financial planners, check out Chapter 11 of Client Psychology, “Automated Decision Aids: Understanding Disuse and Designing for Trust, with Implications for Financial Planning,” which was written by Dr. McCarley.

The Factors Advisors Prioritize When Making Portfolio Allocation Recommendations

Sticking with the theme of evaluating factors which influence financial decision-making, Dr. John Grable, Amy Hubble and Michelle Kruger, all of the University of Georgia, presented a paper titled Do as I Say, Not as I Do: An Analysis of Portfolio Development Recommendations Made by Financial Advisors.

In their paper, the authors examine how financial advisors consider various portfolio development factors (e.g., client's risk tolerance, time horizon, age, etc.) when determining an asset allocation recommendation. The authors note that financial advisors primarily rely on three methods for generating asset allocation recommendations: (1) heuristics (e.g., simple decision rules such as allocation = 100 - age), (2) mean-variance efficiency (e.g., Modern Portfolio Theory), and (3) professional judgment (e.g.., a combination of MPT principles, heuristics, and consideration of other tacit knowledge which may be hard to formalize and articulate). Notably, it is often professional judgment that advisors use in practice, although the precise ways in which advisors utilize various forms of information likely varies—thus the motivation for Grable et al.'s analysis.

The authors administered an online survey to over 200 financial professionals of various backgrounds. Participants were first given a list of twelve factors relevant to investment portfolio allocation and were asked to rank them in terms of relative importance. The advisors were then given client profiles with a high-level of detail about the clients (e.g., background, attitudes toward risk, financial needs, etc.).

The client's time horizon, liquidity need, risk need, and risk capacity stood out as factors that advisors rated as high importance. However, when looking at advisors actual recommendations rather than their ratings of importance, age appeared to be a particularly important factor, and many advisors appeared to apply something akin to the 100 - age rule, even in cases where the objective factors of a client's situation likely should have resulted in different recommendations. Relative to what mean-variance methods would suggest (which is arguably the best benchmark for assessing how advisors "should" make allocation recommendations based purely on financial characteristics such as risk and return), most advisors tended to recommend lower levels of stocks. Notably, the advisors whose recommendations were closest to mean-variance efficient allocations were older, more experienced, more risk tolerant, compensated in a manner other than salary, and held the CLU® designation.

It's this tension between what advisors say they use and actually use to make recommendations which prompted the title of the article, "Do as I Say, Not as I Do." Specifically, while advisors said that factors relevant to mean-variance analysis were most important, their actions (i.e., the actual recommendations they gave) suggested that age and employment status were truly driving allocation recommendations. Thus, if investors want portfolios most consistent with what's recommended in the academic literature, then they should do as advisors "say" and not as advisors "do".

However, the authors are also careful to note that these findings should not be taken as evidence that advisors are wrong in prioritizing age and employment status over other factors. How advisors ought to provide recommendations is still very much an open question.

After all, norms and other common social practices can have a tremendous amount of wisdom embedded in them, even when they aren't intentional and may seem confusing or unexplainable. For instance, economist Peter Leeson has argued that behaviors as bizarre as vermin trials (e.g., holding formal legal trials against rodents and insects accused of property crimes) and trial by ordeals (e.g., determining one's innocence or guilt by dipping their arm in a cauldron of boiling water) were actually rational when the proper context of individual and institutional incentives is understood. If summoning locusts to court might have had some rational basis to it (that even those who participated in such rituals might have struggled to articulate), then the notion that some functional value is embedded in the modern 100 - age rule may not seem so absurd.

So what should advisors do with these findings? It's hard to say when we aren't exactly sure whether advisors should push back against or embrace the tendency to determine allocation recommendations based on age and employment status, but perhaps one takeaway is that there is still tremendous opportunity to be more conscious in our approach to generating client recommendations, as it appears we may struggle to even identify what factors we actually utilize in practice.

Quality of Life in Retirement

Another important topic which received a fair amount of attention at the 2018 Academic Research Colloquium was quality of life in retirement, including both objective forms of well-being (such as mortality and financial well-being among those who experience late-life disability) and subjective forms of well-being (such as relationship quality and life satisfaction in retirement).

The Relationships Between Late-Life Disability, Homeownership, Wealth, and Mortality

In a study titled, Late-Life Disability, Homeownership, Wealth, and Mortality, Dr. Patryk Babiarz of the University of Georgia and Dr. Tansel Yilmazer of Ohio State University examine the effects of late-life disability on one’s health and wealth.

Financial advisors are well aware of the fact that there are costs and benefits to “aging in place” (i.e., trying to stay at home as aging occurs, and adapt the home as necessary to accommodate changing needs). On the one hand, staying in one’s home can provide the highest levels of comfort, independence, and is generally the most affordable option (so long as major modifications to one’s home aren’t needed). Additionally, an often-overlooked downside to alternative living arrangements, such as nursing homes, is the increased risk of morbidity or mortality that can result from infections which may be more likely due to being in close proximity to an unhealthy population, higher levels of antibiotic-resistant organisms, and antimicrobial overuse.

On the other hand, staying in one’s home could be even more detrimental to one’s health if they can no longer adequately care for themselves, and factors such as social isolation could result in worse health relative to what one may achieve in an environment with greater social opportunities. Of course, finances can also present a barrier to institutional living arrangements (e.g., nursing homes or assisted living facilities), so the decisions associated with late-life disability present a complex web of trade-offs that influence one’s health and wealth.

To investigate these relationships, Yilmazer and Babiarz examine whether the elderly with deteriorating health and functional capacity exit homeownership (i.e., sell their homes and move elsewhere, such as into a nursing home, assisted living facility, or with other family members), and, if so, how that exit influences their health, wealth, and mortality.

The authors note that we don’t yet know whether aging in place extends the lifespan. Additionally, there are considerable challenges with measuring health in older ages. Nonetheless, using the Health and Retirement Study, the authors examine how one’s difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs)—such as bathing, self-feeding, dressing—and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)—which are part of a broader category of activities that are not essential to the most basic levels of daily living yet still important for living independently, such as managing money, shopping, and preparing meals—predict homeownership exit.

The authors find that there are important differences between single and coupled households. Couples tend to remain homeowners until struggling with four ADLs, whereas a single individual will exit homeownership as soon as they experience difficulty with one ADL. Among specific ADLs, ability to bathe is the strongest predictor of leaving one’s home for both single and coupled households. Among IADLs, inability to prepare a hot meal was the strongest predictor of a single individual exiting their home. Additionally, the threshold for leaving one’s home seems to rise as one gets older, with older homeowners moving only once they experience difficulties with as many as five or six ADLs.

Notably, just because someone moves out of their home does not mean that they no longer own their home, but as would be expected, when people leave their homes they do tend to sell their home and experience sharp declines in both housing and total wealth (presumably due to higher living expenses in an institutional setting). Bequest intentions may also decline once one has left their home, potentially due to the financial realities of needing to cover one’s expenses. Nonetheless, exiting homeownership may sometimes be what’s best for a household, as Babiarz and Yilmazer find that doing so reduces the likelihood of mortality for those having difficulties with IADLs.

As a result, financial advisors should be cognizant of the ways in which difficulty with ADLs or IADLs may influence a client’s financial plan. While coupled households may have more potential to adapt to some difficulties, single households may be at even greater risk of needing to quickly exit homeownership. And, in any case, conversations should ideally be started sooner with clients, so that proper financial arrangements can be made for clients to be prepared to deal with changes in housing that may arise.

Spending, Relationship Quality, and Life Satisfaction in Retirement

In a study titled Spending, Relationship Quality, and Life Satisfaction in Retirement, Michael Finke of The American College, Nhat Ho of Eastern New Mexico University, and Sandra Huston of Texas Tech University examine how spending and relationship quality influence life satisfaction in retirement.

As the authors note, “Prior economic research has focused on the relation between money and well-being, rather than how resources are used to elicit life satisfaction in retirement.” Beyond the obvious reason that we generally believe it is good for individuals to experience satisfaction in their lives, the authors note that life satisfaction is an important measure to consider as it provides a complementary measure to consumer preferences and social welfare. In other words, analyzing self-reported life satisfaction is worthwhile because it can provide one more dimension to a multifaceted understanding of “well-being,” which can also include more objective measures (e.g., those revealed by consumer choice), as well as social elements which are distributed broadly across a community or society (e.g., environmental quality).

In order to investigate how resources are used to elicit life satisfaction in retirement, Finke et al. group retirement spending into 11 categories:

- Durable spending (e.g., appliances)

- Housing spending

- Auto spending

- Auto-related spending (e.g., maintenance)

- Utility spending

- Housekeeping and yard spending

- Health spending

- Leisure spending

- Clothing and personal care spending

- Gifts spending

- Food spending

Using the Consumption and Activities Mail Survey (CAMS), a supplementary survey conducted alongside the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the authors were able to get detailed household spending information, which they combined with data on relationship quality (including quality of one’s relationships with a spouse, children, and other friends and family, if applicable), self-reported life satisfaction, and other household characteristics.

As would be expected, the authors found that spending amongst various categories varies considerably. For instance, wealthier households can afford to spend more on leisure goods than poorer households. Ultimately, the authors conclude:

The results provide evidence to suggest that leisure spending, health status, and spousal and friend relationships have the greatest impact on creating life satisfaction during retirement, while other types of spending and children relationships do not.

Finke et al.’s findings are consistent with prior research which suggests that the type of spending that buys the most happiness is experiential purchases (rather than mere “stuff”). The authors’ findings also provide important nuance to the often-mentioned relationship between marriage and life satisfaction, as marriage is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction in retirement, but only if marriage quality is high (i.e., low-quality marriages result in less life satisfaction). The authors also note that the results suggest that proximity to one’s friends may be a more important consideration than proximity to one’s children in retirement.

The authors suggest that advisors should help their clients accurately assess the costs and benefits of prospective life changes. For instance, their findings suggest that relocating to be closer to one’s children—a common desire among retirees—may actually decrease life satisfaction if it means retirees have to move away from their friends. And to the extent that the children of retirees live somewhere that could make leisure spending difficult for those retirees (e.g., art aficionados in Manhattan relocating to the oil fields of North Dakota), then the effects of leaving one’s friends and leisure opportunities could be doubly harmful to life satisfaction.

Racial Diversity in Financial Services

Another theme receiving considerable attention at the ARC was racial diversity. Consistent with the launch of the CFP Board’s “I AM A CFP® PRO” campaign in April of 2017, which aimed to promote career interest among young adults, women, and people of color, the 2018 ARC included topics related to issues important to racial diversity among both practitioners and consumers of financial services.

The Role of Empathy in Black Consumer Choice to Use a Financial Advisor

In their article, If You Get Me, I’ll Hire You: Role of Empathy in Black Consumers’ Choice to Use a Financial Advisor, Dr. Danielle Winchester and Dr. Roland Leak, both of North Carolina A&T State University, examine whether an advisor’s ethnicity affects perceived empathy and willingness of black consumers to seek financial advice.

Given the large rise in black households earning more than $200k and the 9 million black baby boomers that are expected to retire within the next 20 years, Winchester and Leak note that black consumers will increasingly be seeking the advice of financial advisors. However, black consumers also face unique challenges in the marketplace. For instance, due to the only 14% of black consumers who work with a financial planner (versus 26% among the general U.S. population) and the low levels of diversity within the financial advisory industry, Winchester and Leak note that search costs (and monitoring costs) may be greater for black consumers.

Utilizing signaling theory, the authors explore how racial identification could serve as a signal that reduces the information asymmetry that is inherent to a buyer-seller relationship. In particular, because empathy is an unobservable trait (i.e., our words or actions may convey empathy, but both someone with genuine empathy and someone with fraudulent empathy would largely behave the same way, making it hard to sort out real empathy from fake empathy) it is possible that ethnicity of a financial advisor could serve as a signal of genuine empathy. In other words, when consumers aren’t certain which advisor should be trusted, they may be more likely to trust someone of the same ethnicity, anticipating that the advisor will be more likely to understand (and have empathy for) their unique needs and circumstances. And if this is the case, then it could be possible that the resulting empathy influences one's likelihood of using a financial advisor.

To investigate these potential relationships, Winchester and Leak presented images of three different financial advisors (one white advisor and two black advisors of varying degrees of Afrocentricity) to 92 black undergraduate students. Additionally, they examined student ideology, particularly the degree to which students expressed a belief in color blindness (i.e., belief that race should not be prescriptive in judgments about individuals).

The results indicated that the white advisor presented to participants was perceived as less empathetic, while the two black advisors were viewed as equally empathetic. Additionally, black consumers also indicated a greater likelihood of utilizing the services of the black advisors. Notably, an interaction effect was present between weak color blindness and low perceived empathy, indicating that levels of black consumer preference may vary based on one’s ideology.

Ultimately, the results highlight the importance of racial diversity in the financial services industry from the consumer’s perspective, as there may be at least a material segment of black consumers who appear to perceive black financial advisors as more empathetic to their situation (and therefore more desirable to work with), which means a lack of black financial service professionals (and the barriers that lead to that underrepresentation) could result in lower rates of financial services utilization, and lower consumer financial well-being as a result.

Overall, the second Academic Research Colloquium again brought together a strong mix of academics and practitioners to present and discuss financial planning research. Notable challenges (and opportunities for growth!) in coming years will include the launch of the Center for Financial Planning’s new academic journal (Financial Planning Review), the push to establish the ARC as the core conference interview location for financial planning faculty positions, and continuing to attract a diverse group of scholars to build and contribute to the financial planning knowledge base. Only time will tell if the Center for Financial Planning can be successful in their pursuit of becoming the “academic home” of financial planning research, but the ARC continues to be a strong conference for both academics and financial planners interested in research.

A full list of accepted papers and posters can be accessed on the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning’s website. The 2019 Academic Research Colloquium will be returning to DC from February 18-20, 2019.

So what do you think? Did you attend the 2018 Academic Research Colloquium? What factors do you consider when determining asset allocation for your clients? Do you think retirees should be more careful relocating just to be closer to their children? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply