Executive Summary

From February 19th through February 21st, the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning hosted their third annual Academic Research Colloquium (ARC) for Financial Planning and Related Disciplines in Arlington, VA. This year's event saw a 20% increase in attendance, bringing together roughly 230 attendees, of which about 35 were practitioners, to share and discuss research relevant to the financial planning profession, as a part of the CFP Board Center’s longer-term goal of establishing itself as the “academic home” for the financial planning profession.

In this post, Derek Tharp – lead researcher at Kitces.com, and an assistant professor of finance at the University of Southern Maine – provides a recap of the 2019 CFP Academic Research Colloquium, and highlights a few particular research studies with relevant takeaways for financial planning practitioners.

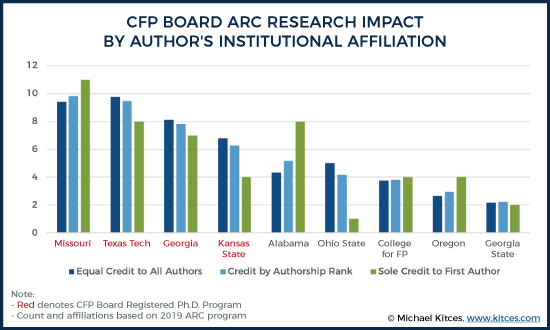

The 2019 CFP Academic Research Colloquium again had a strong showing from CFP Board-Registered Ph.D. programs, with scholars from Missouri, Texas Tech, Georgia, and Kansas State producing nearly 32% of all research (when weighted by type of presentation and authorship rank). Additionally, Ohio State, Alabama, and the College for Financial Planning contributed another 13% of total research. Despite the concentration among top programs, the ARC remains an academically diverse event, drawing in scholars from a total of 69 institutions, including Harvard, Wharton, and Stanford.

The colloquium featured a wide breadth of topics. Some particularly relevant themes for financial planning practitioners included a number of studies on financial psychology of both clients and practitioners, including measuring brain activity during financial conversations to determine whether planning or emotional areas of the brain were activated during financial conversations, examining the tools that do (and do not) work for measuring risk-taking behavior, assessing perceptions of success and satisfaction among female advisors, and identifying gaps between perceptions of both financial planning graduates and employers regarding student preparedness for a career in financial planning. In addition, there was research on the impact advisors may have on clients- both good and bad - including differences in financial decision-making among households that use a financial planner versus a transactional advisor, the use of municipal bonds among advisor-assisted investors, and the characteristics of those who report being victims of investment fraud.

Overall, the third Academic Research Colloquium again brought together a strong mix of academics and practitioners to present and discuss financial planning research. However, some considerable challenges and opportunities going forward include continuing to develop Financial Planning Review into a high-impact journal, dealing with (potentially) declining institutional and sponsorship support, and the Center’s general push to continue to establish the ARC as the “academic home” of financial planning. Only time will tell if the Center for Financial Planning will be successful in their pursuit, but the ARC continues to be a conference worthy of attending for both academics and practitioners who wish to engage in academic research.

2019 CFP Academic Research Colloquium

From February 19th through February 21st, the CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning hosted their third annual Academic Research Colloquium (ARC) in Arlington, VA. The event saw a 20% increase in attendance, bringing together 230 attendees, of which roughly 35 were practitioners, to share and discuss research relevant to the financial planning profession. The CFP Academic Research Colloquium is part of a longer-term goal to establish the CFP Board Center for Financial Planning as the “academic home” for the profession.

Consistent with the 2017 and 2018 ARCs, there was a strong showing among some core academic financial planning programs. Not surprisingly, the four universities with CFP Board-Registered Ph.D. programs—University of Missouri, Texas Tech University, University of Georgia, and Kansas State University—led all universities in terms of papers accepted for an oral or poster presentation, and were followed by programs with an emphasis on financial planning, including University of Alabama, Ohio State University, and the College for Financial Planning.

For the purposes of determining research impact, we have used three different scoring metrics to analyze this year’s ARC. In all cases, oral presentations (breakout sessions where authors present their findings to an audience) were given twice the weight as research selected for a poster session (a less formal presentation of research that takes place within in a large meeting space with many posters available for review at one time). Generally speaking, authorship rank (i.e., which author is listed first, second, etc.) is an indication of how involved each author was in the project. Therefore, three different scoring methods were used as an attempt to capture different ways of assessing how involved authors were in producing the research.

The first method was to assign equal credit to all authors. An oral presentation of a sole-authored research paper would earn an institution a score of 2.0 (1.0 for a poster session), whereas an oral presentation of a paper with five coauthors would earn the institution of each respective author a score of 0.4 (0.2 for a poster session). By this metric, Texas Tech ranked first, followed by Missouri, Georgia, and Kansas State.

An alternative approach to award all points to the institution of the first author listed on a paper, regardless of the number of coauthors. Using this approach, a paper presented at an oral session would earn the first author’s institution a score of 2.0 (1.0 for a poster session) regardless of how many coauthors were on a paper or what their affiliations were. By this metric, Missouri ranked first, followed by Texas Tech, Georgia, and Kansas State.

A “middle of the road” approach is to award a higher share of points to institutions with authors ranking higher on a paper, while still awarding some credit to institutions of lower-ranking authors on a paper (see more scoring details here). By this metric, Missouri ranked first, followed by Texas Tech, Georgia, and Kansas State.

From an institutional perspective, perhaps the most notable observation over the first three years of the ARC has been the rise of University of Missouri’s program. In a short time, Missouri has gone from not being a CFP Board-Registered Ph.D. program during the 2017 ARC (and not ranked among the top contributors), to having the largest research impact based on two of the three metrics used to assess the 2019 ARC.

Notwithstanding the strong presence from top financial planning programs—as the four doctoral programs accounted for a combined 32% of all research, plus another combined 13% from Alabama, Ohio State, and College for Financial Planning—the diversity of research by institution was consistent with the 2018 ARC, and more diverse than the 2017 ARC. Overall, a total of 69 institutions were represented among authors at all ranks, and 42 at the first author rank.

Industry sponsorship of the ARC appeared to be down in 2019, though, with no named event sponsor (as was the case in 2017 and 2018, with Merrill Lynch being the signature sponsor for each prior ARC), and only two firms—TD Ameritrade Institutional and Northwestern Mutual—electing to support $2,500 best paper awards (down from four sponsors in 2017 and three sponsors in 2018). Additional sponsors included Zahn (lanyards and a refreshment break) and Wiley (a general session regarding the Center for Financial Planning’s new journal, Financial Planning Review). Exhibitors included the CFP Board, CFP Board Center for Financial Planning, Dimensional Fund Advisors, MoneyGuidePro, Palgrave Macmillan, PlanPlus, Wiley, The Institute for Behavioral and Household Finance, NAPFA, and the National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE).

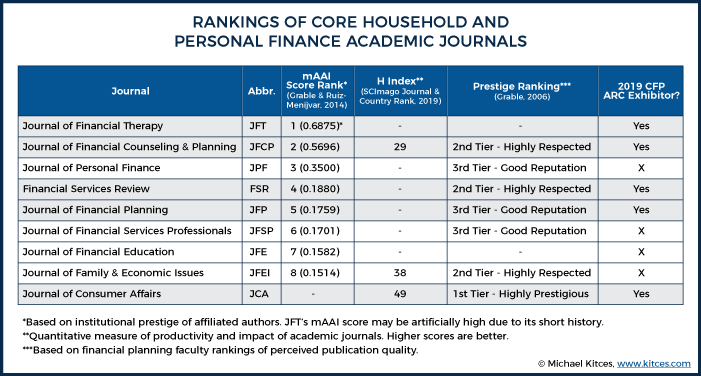

Journal exhibitors again included four of the top five core household and personal finance journals identified by John Grable and Jorge Ruiz-Menjivar in 2014: Financial Services Review (Academy of Financial Services), Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning (Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education), Journal of Financial Planning (Financial Planning Association), and the Journal of Financial Therapy (Financial Therapy Association). Additionally, although not included among the “core” household and personal finance journals identified by Grable & Ruiz-Menjivar, the Journal of Consumer Affairs (American Council on Consumer Interests) was also an exhibitor, which is one of the highest ranking journals that regularly publishes content relevant to personal and household finance.

The Center for Financial Planning’s New Journal: “Financial Planning Review”

The editors of the Center for Financial Planning’s new journal, Financial Planning Review (FPR), were also in attendance. Dr. Vicki Bogan (SC Johnson College of Business, Cornell University), Dr. Chris Geczy (Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania), Dr. John Grable (University of Georgia), and Dr. Charles Chaffin (CFP Board Center for Financial Planning) led a keynote session in which they shared information about the journal’s first year in publication.

In 2018, Financial Planning Review formally launched as a journal, and published the following articles:

Volume One, Issues 1-2

- Perspectives on mental accounting: An exploration of budgeting and investing. By C. Yiwei Zhang and Abigail Sussman.

- The relationship between financial planner use and holding a retirement saving goal: A propensity score matching analysis. By Kyoung Tae Kim, Tae-Young Pak, Su Shin, and Sherman Hanna.

- Tightwads and spendthrifts: An interdisciplinary review. By Scott Rick.

- Household financial planning strategies for managing longevity risk. By Vickie Bajtelsmit and Tianyang Wang.

Volume Two, Issues 3-4

- The existence and persistence of financial anomalies: What have you done for me lately? By John Guerard and Harry Markowitz

- Exploring the relationships between impatience, savings automatic, and financial welfare. By Brianna Middlewood, Alycia Chin, Heidi Johnson, and Melissa Knoll

- The pivotal role of fairness: Which consumers like annuities? By Suzanne Shu, Robert Zeithammer, and John Payne.

- Supportive and mitigating factors associated with financial resiliency and distress. By Vibha Bhargava, Lance Palmer, Swarn Chatterjee, and Richard Stebbins.

The editors noted that a significant benefit of submitting academic research to FPR is the quality and speed of peer reviews (first response in ~1 month, which is actually very fast for academic journals). The hope of the editors continues to be that FPR will be the journal that researchers choose to submit their highest quality work to.

Another notable announcement was that FPR has extended their FinTech Special Issue call for papers until December 31st of 2019. For the time being, you can view the prior FinTech call for papers here.

Financial Psychology

Consistent with past ARCs, financial psychology was again a popular topic. From how financial conversations influence brain waves, to how effective risk tolerance questionnaires are at actually predicting financial risk-taking behavior, there was a wide range of interesting psychological research presented.

How Financial Conversations Influence Brain Waves

One particularly unique study at the 2019 ARC included the use of a device to assess how brain waves change while having financial conversations. In a study titled, The way consumers and clients respond to financial conversations: Investigation with measurement of EEG signals, Wookjae Heo of South Dakota University used an electroencephalography (EEG) headset to monitor and record brain activity of survey participants engaging in financial conversations.

Within his study, Heo had participants wear a headset that looks similar to the one below. This headset allows researchers to measure brain waves via voltage fluctuations on one’s scalp. As Heo describes, one way in which brain waves can be classified is their “activeness.” Low frequency waves—including Delta, Theta, and Alpha waves—measure in lower Hz frequencies and are associated with states or activities such as relaxation, meditation, and unconscious body functions. By contrast, high frequency waves—including low Beta, high Beta, and Gamma waves—measure in higher frequencies and are generally exhibited in activities ranging from relatively light activity (low Beta) to high activity (Gamma).

Activation of different regions of the brain can also be an indication of different types of brain functioning. For example, activation in the frontal lobes may be associated with thinking or planning, whereas activation in the right temporal lobe may be associated with facial recognition. In reality, the functioning of a brain is highly complex. Some degree of activation is occurring in all areas of the brain at all times. Nonetheless, certain combinations of activation can yield insight into an individual’s mental state.

Activation of different regions of the brain can also be an indication of different types of brain functioning. For example, activation in the frontal lobes may be associated with thinking or planning, whereas activation in the right temporal lobe may be associated with facial recognition. In reality, the functioning of a brain is highly complex. Some degree of activation is occurring in all areas of the brain at all times. Nonetheless, certain combinations of activation can yield insight into an individual’s mental state.

Heo was specifically interested in activity within the parietal and temporal lobes, which together could provide insight into whether an individual’s brain was in a resting or active state (indicated by alpha waves in the parietal lobes), as well as whether an active state was functioning in the areas of planning and decision-making (low- and high-beta waves in the left temporal lobes) or emotion and motivation (low- and high-beta waves in the right temporal lobes).

Heo used an experimental design to assign individuals to either a treatment group (engaged in a conversation about financial topics) or a control group (engaged in a conversation about one’s day and general background information). The sample size was small (N = 19), but this is not uncommon for exploratory research of this type. Participants were also given a risk tolerance questionnaire at the beginning of the experiment.

After controlling for relevant demographic and other characteristics, Heo found that when engaging in a financial conversation, there were both emotional responses and decreased planning function. The latter is a particularly interesting physiological response from the perspective of a financial planner, who typically wants to engage in a conversation to increase planning function. Heo also found that risk tolerance influenced responses in some nuanced ways, including an amplification of emotional responses.

While the results from Heo’s study are likely too preliminary to yield much practical insight for engaging with clients (not due to any fault of Heo’s…it just takes time to replicate findings, explore other contextual factors that could influence responses, etc.), his study does provide an interesting glimpse into the future of financial planning laboratory research and the potential that exists to provide greater insight via clinical research.

(Derek’s Note: If research like this is of interest to you, researchers like Heo are always in need of funds to recruit respondents, invest in new equipment, etc. Clinical research in financial planning is in such an early stage that even small contributions can have a fairly large impact, so reaching out to scholars to explore ways to support their research is one great way to get involved in the future of financial planning research.)

Comparing Questionnaires Used to Predict Financial Risk-Taking Behavior

In a study titled Predicting Financial Risk Taking Behavior: A Comparison of Questionnaires, John Grable, Amy Hubble, Michelle Kruger, and Melissa Visbal examine the predictive validity of different risk tolerance questionnaires.

Because while most financial advisors use some form of risk tolerance questionnaire for compliance purposes, it’s not clear whether such questionnaires actually provide an accurate assessment of a client’s risk tolerance. To try and explore the validity of different types of risk tolerance measures (i.e., whether risk tolerance measures do in fact measure the extent to which investors will tolerate risk), Grable et al. conducted an exploratory study which included surveying respondents and then having them participate in a financial risk-taking activity to see if their actions aligned with the risk tolerance questionnaire results.

Economic Measures of Risk

Grable et al. explain that there are two different ways in which psychologists and economists tend to measure risk. Economists tend to rely on measures of risk aversion, which is often assessed via gamble or lottery type questions. A question may be framed as respondents evaluating whether they would take a 50-50 chance of receiving a higher or lower financial outcome compared to the status quo. Such questions can then be repeated, with different higher and lower outcomes, to get an estimate of an individual’s overall risk aversion. (This is similar to the approach that risk tolerance software tools like Riskalyze use.)

In Grable et al.’s study, respondents were first asked to assume they are the sole earner for a family and get offered a new job that is equally as good as their current job, with the caveat that accepting the new job will result in a 50-50 chance that they will either double their income or cut their income by one-third, over the remainder of their life.

If individuals were willing to take this gamble, then they were subsequently asked whether they would take the same gamble if there were a 50-50 chance they would either double or halve (as opposed to just cut by 1/3rd) their new income by making the change. An individual who answered “yes” to both questions would effectively be “risk-neutral” since they are willing to take the gamble despite the fact that the expected value is equal to zero.

If an individual answered no to the first question, they were subsequently presented with a 50-50 chance of doubling their income or cutting it by 20%. Individuals who answered no to both questions would be said to exhibit high risk aversion since they were unwilling to take a gamble even though the expected value was fairly large (more upside for income doubling compared to the downside of "only" a 20% cut if income decreases).

Psychometric Measures of Risk

A second approach to measuring risk tolerance is to use psychological scales that assess one’s broad willingness to take financial (or other) risks. Grable and Lytton (1999) created a multidimensional risk tolerance scale that is comprised of 13 multiple choice items including questions on topics such as how one’s friends would describe their risk-taking behavior and how individuals would invest an unexpected lump sum of cash (the full questionnaire can be accessed here). The responses to different questions are then scored, and an overall assessment of one’s willingness to take risk is provided. (This is effectively the approach used by risk tolerance software solutions like FinaMetrica.)

When the ability to ask respondents multiple questions is limited, researchers may also rely on broad single item measures that attempt to gauge an individual’s overall willingness to take risk. For example, Grable et al. also asked respondents to rate oneself as a financial risk taker on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 indicating the highest level of risk taking. This approach generally falls within the psychological measures as well, because single- or reduced-item measures are typically assessed in terms of their validity and reliability in comparison to larger scales that are believed to be valid and reliable.

Risk-Taking Experiment

To compare these two approaches, a sample of individuals (N = 164) were first recruited to complete an online survey that included different economic and psychological measures of financial risk-taking behavior. From this full sample, 40 participants were randomly selected to participate in a financial risk-taking behavior.

If selected, when a participant arrived at the research team’s office to receive their survey incentive, they were offered an opportunity to win an additional $10 or $20 by playing a game (the interviewer stood next to a Las Vegas-style craps table while asking this question). If individuals were not interested, they could simply keep their $10 incentive.

If the participants were interested in the gamble, then they were told they must wager their $10 incentive to participate, and could choose between one of two games that varied in terms of probability of winning and potential winnings (with a lower probability wager offering a potential payout of an additional $20 versus $10 under the higher probability wager). Before rolling, participants were given notification of their true odds (50% to win $10 or 25% to win $20) and asked if they would like to change their decision or withdraw from the game entirely and keep their original $10. Ultimately, regardless of what an individual decided (play or not play) or the outcome (win or lose), they were all awarded with a full $30 for participating.

The Efficacy Of Different Risk Tolerance Assessments

After the conclusion of their experiment, Grable et al. found that when it came to predicting who would participate in the wager when the odds were unknown (or at least not explicitly stated), the Grable & Lytton questionnaire approach (henceforth the “G&L scale”) performed the best. Those who scored highest on the G&L scale also were the most likely to take the greatest risk in the game, while those who scored as more or less risk-averse on the economic-tradeoffs scale did not necessarily exhibit the same risk-taking proclivities in practice when presented with the risk-taking game. In fact, the results also showed that the economic scales were not correlated to the psychometric theory-based G&L scale at all, nor to the single-item measure of self-assessed risk tolerance.

As a result, the researchers conclude that the G&L scale (or more generally, a psychometrically validated risk tolerance questionnaire approach) provides the best insight into actual real-world risk-taking behavior, at least as assessed within this study. The authors do note that certain factors about the study—including whether the amount felt “meaningful” to the participants, or whether individuals might have behaved differently by feeling as though they were wagering “found money”—could have influenced the results. Overall, however, the G&L scale demonstrated the best validity within this context, and financial planners should consider the implications of using measures to assess risk tolerance that are actually assessing risk tolerance.

Success and Satisfaction of Women in Financial Planning

Staying within the realm of psychological assessment, but switching the focus from consumers of financial planning to producers (i.e., advisors themselves), a study titled Success and Satisfaction of Women in Financial Planning by James Pasztor, Aman Sunder, and Rebecca Henderson, examined how women in financial planning perceive success and satisfaction within their careers.

While objective forms of success are generally much easier to measure (income, promotions, etc.), subjective perceptions of success are relevant to understanding how one may perceive their own standing within an occupation. Furthermore, career satisfaction—a form of subjective well-being—may both influence or be influenced by one’s perceptions of success.

Pasztor et al. note that past research has found gender differences in participation, earnings, and career outcomes within the financial planning profession, as well as gender differences in subjective assessments of success and satisfaction more generally. For example, one prior survey found that male financial advisors were more likely to own a practice, less likely to work in a small practice, more likely to generate $300k or more in production, and less likely to be in a salaried position.

Prior research has also found that certain factors—such as personality—can influence how one assesses their satisfaction with their life, career, or other domains within their life. For example, extraverted individuals tend to provide a rosier assessment of their satisfaction compared to introverted individuals, even when objective life factors are otherwise similar. Furthermore, Pasztor et al. note that prior research suggests that extraverts are also more likely to take action and change their circumstances when there may be a poor fit between one’s occupational preferences and the institution they work for.

To explore perceptions of success and satisfaction among women in the financial planning industry, Pasztor et al. conducted surveys of financial planners who were attending CFP CE courses hosted by the College for Financial Planning.

Respondents self-reported their perceived success and satisfaction on 10-point scales. Overall, female respondents (N =73) were more likely to be CFP certificants, and report that the CFP certification was relevant to their profession when compared to male respondents (N = 136). The authors also found a lower correlation between success and satisfaction among women when compared to men. Women were also more likely to have a solo practice when compared to men. Among Big Five personality traits, gender differences were not observed in levels of extraversion, openness, and emotional stability, but women did rate higher on agreeableness and conscientiousness when compared to men (which is consistent with prior Kitces Research on the Big Five and financial advisors as well).

After controlling for age, experience, firm size, undergraduate education major, and Big Five personality traits, Pasztor et al. found that female financial planners were less likely to report high levels of satisfaction with their careers when compared to males. The authors note that, when compared to males, females were more likely to report feeling highly satisfied with their careers when working within a solo or small firm environment. However, females working in solo or smaller firms did report feeling less successful when compared to females within larger firms.

The authors also examined some qualitative factors related to one’s desire to pursue a career in financial services, finding that women were more likely to desire independence and prefer to avoid a corporate environment when compared to men.

Notably, as is the case with all studies related to gender differences, it is important to remember that just because there may be evidence of differences between groups does not mean that those same differences apply to each/all individuals within the group. This is particularly true when individuals may self-select into certain roles, such as the case of choosing a career. Therefore, general findings that women prefer a small firm environment should not be perceived as a finding that applies to all women within the industry.

Consequently, it would be wrong to, say, interview otherwise equally qualified male and female candidates for a position at a large firm, and conclude that the female candidate is less likely to enjoy the large firm environment. Particularly because the female candidate must go out of her way to identify the opportunity within a large firm and then apply for that position, differences that may exist among a group broadly do not necessarily apply to her as an individual.

In other words, despite the insight that research on gender differences can provide in understanding the world, it is always important to still treat individuals as individuals. Research such as Pasztor et al.’s study provides important insight in the perceptions of success and satisfaction among females within the industry, but it would be wrong to use these (or similar) insights to infer differences about individuals.

What Do Financial Planning Students Entering the Profession Want/Expect from Employers?

Chris Browning, Mark Evers, and Amber Lemmon explore the expectations of students pursuing a career in financial planning within a study titled, Insights from Advisors and Financial Planning Students.

Browning et al. note that the financial advisory landscape has been shifting from a product-centric industry to an advice-centric industry. As a result, the researchers were interested in what gaps may exist between the expectations of students and the firms that can hire them coming out of school.

The authors examined perceptions by surveying both students at various CFP Board-Registered programs (N = 121) and industry professionals (N = 60) regarding preferences and expectations for employment within the profession. Roughly 82% of the advisors surveyed came from an RIA background, followed by advisors at broker-dealers (10%), or from other larger financial institutions (3%). About 72% of the advisors surveyed were fee-only, and the remainder were fee and commission. Though there was a large gender gap among advisor respondents (73% male vs. 27% female), student respondents were relatively more balanced (54% male vs. 46% female).

Overall, two-thirds of advisors felt that students entering the profession had too high of employment expectations. This was reflected among salary expectations, with advisors overwhelming expecting newly graduated students to earn in the $45-$54k range, whereas the most common expectation among students was the $55-$64k range, with a significant number of students expecting to earn $65k-$74k, and some even expecting $85k or more.

Advisors and students did seem to largely be aligned on understanding the importance of the CFP designation, although over 50% of students were still either not going to sit for the exam (3%), undecided about sitting for the exam (14%), or plan to wait until they actually have their first financial planning job before sitting for the exam (37%). While some hesitation may be warranted if students are unsure about whether they intend to pursue a career in financial planning, this likely presents an opportunity for those who are truly certain they want to pursue a career in financial planning to credibly signaling their commitment to prospective employers by taking their CFP exam as soon as possible after graduation (or even before they graduate).

On the other hand, while advisors did seem to value the CFP designation, they did not appear to have a strong preference for hiring students out of CFP programs per se. Consistent with this finding, advisors were okay with students not necessarily sitting for the exam immediately after graduation—seeming to instead prefer traits such as communication skills, willingness to learn, and eligibility to sit for the exam.

The area, by far, that advisors rated students to be most prepared to be successful in was technology/software. Interestingly, however, students rated themselves as the least prepared to be successful in this area, reporting that they were better prepared to succeed in areas such as working hard and time management. Advisors rated students as least prepared in the areas of client communication and hard work. A fairly sizeable gap also existed between student and advisor perceptions of student preparedness in technical areas, with advisors feeling as though students were more prepared than students assessed themselves.

Student and advisor expectations regarding factors that contribute to career satisfaction were, for the most part, aligned with one another. When considering a first job in financial planning, students reported caring the least about location and pay, while having a strong preference for having an ability to make a positive difference.

Overall, perceptions of advisors and students appear aligned in some ways, but not all. Based on a comparison of perceptions, students may be overconfident in the areas of communication, time management, and work ethic, as well as underconfident in their analytical and technological skills.

Salary expectations of students also appear to be higher, although it’s worth noting that the differing expectations, in this case, do not necessarily mean that the expectations of either side are out of line. While there is a general tendency for many undergraduate students to have overly optimistic perceptions of their future income, it’s also true that (a) these students were in CFP® Board-Registered programs, and (b) advisors reported that they weren’t necessarily looking to hire grads out of CFP Board-Registered programs. It’s possible that at least some of the students with high expectations have those expectations because they are some of the most desirable candidates in the field (and know their worth in the right market!), whereas the advisors surveyed for this study may prefer to hire less polished candidates at a lower cost. Nonetheless, it’s important for both sides to consider whether their expectations may or may not truly reflect reality.

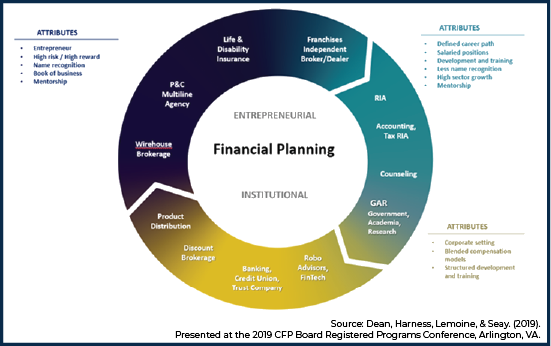

On a related note, while technically occurring at the CFP Registered Programs Conference following the CFP ARC (and not the ARC itself), Professors Luke Dean (Utah Valley University), Nathan Harness (Texas A&M), Craig Lemoine (University of Illinois), and Martin Seay (Kansas State University) gave an excellent presentation on student-career fit within the many different areas within financial planning. Noting that students can differ substantially in terms of skills and personality for different types of positions, the professors developed a resource that is designed to help students understand where they may fit within the financial planning industry. While it is still a work in progress, and the authors do not claim to have captured all avenues perfectly, they have agreed to share it so that financial planners have a resource available to help educate future and current professionals about the opportunities that exist within the profession. If you are involved with a local university chapter of FPA or otherwise engage with folks entering the profession, you may wish to pass it along to them.

Research on How Consumers Engage with Financial Advisors

Another broad theme which received a fair amount of attention at the 2019 Academic Research Colloquium was research on consumer engagement with financial advisors, including which households tend to use financial planners rather than brokers, characteristics of those who are most likely to be victimized by investment fraud, and how consumers tend to use municipal bond investments in their portfolios.

Who Uses Brokers vs. Advisors?

In a paper titled Financially Sound Households Use Financial Planners, Not Transactional Advisors, David Blanchett explores the ways in which households make financial decisions when influenced by either financial planners, transaction financial advisors, friends, or the internet.

Using the six most recent waves (2001 to 2016) of the Survey of Consumer Finances, Blanchett assesses the quality of financial decisions made by households influenced by different sources of information.

Specifically, Blanchett looks at five different aspects of decision-making, including emergency savings, saving habits, revolving credit card balances, life insurance coverage, and portfolio risk levels. Blanchett found that households made the best financial decisions when working with a financial planner, followed by (in order) the internet, friends, and then those working with a transactional advisor.

Not surprisingly, the internet has grown in popularity as a source of information for making financial decisions. In 2001, only 3% of households were using the internet as their primary source of information, but that number grew to 40% in 2016. Blanchett notes that the quality of outcomes associated with those who use the internet as their primary source has been declining over time, which should perhaps not be surprising when considering the other ways in which tech-savvy early adopters (usually fairly high in intelligence and good at seeking out information) differ from, say, the median Facebook user of today. Over that same time period, the use of a financial planner has grown from 10% to 18%, while the use of a transactional advisor has fluctuated yet remained fairly stable around the 16%-18% level.

One issue with using publicly available datasets to evaluate the use of financial planners is that the way the use of financial advisors is measured in each dataset contains significant limitations. Heckman et al. (2017) examined this topic in-depth, ultimately concluding that although each data set has issues, the SCF (as used by Blanchett) has one of the most promising measures. Specifically, the SCF asks respondents:

What sources of information do you (and your family) use to make decisions about savings and investments? (Do you call around, read newspapers, magazines, material you get in the mail, use information from television, radio, the internet or advertisements? Do you get advice from a friend, relative, lawyer, accountant, banker, broker, or financial planner? Or do you do something else?)

For the purposes of his analysis, Blanchett assumes that anyone who selected “financial planner” from the set of options is using a financial planner, whereas anyone who selected “banker” or “broker” is using a transactional advisor. The sample of respondents was restricted to only those between 25 and 55 in age, with at least $5,000 in financial and retirement assets, and at least $25,000 in income (since it was assumed that a household with no assets or income would be unlikely to seek financial advice from a financial planner in the first place).

To determine whether households were making prudent financial decisions, Blanchett relies on various rules to assess the prudence of observed household characteristics. For example, a portfolio was assumed to be risk-appropriate if a household’s level of equity investment in retirement assets was within 25 percentage points of the Morningstar Moderate Lifetime Index (i.e., if the Morningstar Moderate Lifetime Index contains 60% equity at a given age, values of anywhere from 35% equity to 85% equity would be classified as prudent).

Households were further assumed to be making prudent decisions if they had a savings plan in place, held at least one-times annual wage income in life insurance, did not have a revolving credit card balance, and had at least three months’ worth of income in an emergency fund.

An aggregate score of financial decision-making is then generated. When averaging across all households within a given category, only those using a financial planner scored above average across each three-year time period from 2001 to 2016. Those using a friend or transactional advisor scored below in almost all years (and in years in which these categories measured above average, it was only very slightly above average). In 2001, users of the internet measured well above all other households, but in all subsequent survey years, internet users have ranked below those who use a financial planner. In all years prior to 2016, internet users ranked at or near the second highest rank but came in with the lowest ranking of all groups in 2016. Households using financial planners ranked as the highest of all groups in each year except 2001.

Blanchett’s regression results, which allow him to control for other factors simultaneously, yield similar findings—i.e., that households using a financial planner achieve the best outcomes. Blanchett does note that it is possible that the relationship identified is endogenous since it is possible that there is selection bias present and it is not the use of a financial planner per se that is driving the results. In other words, it may not be that those using a financial planner are adopting better financial habits because of the planner, but instead that those who are most likely to make good financial decisions and proactively plan for their futures both have good financial habits and a tendency to seek out financial planners for support.

Unfortunately, this is a hard issue to address given the nature of the data available. However, this is a topic that future research will hopefully delve into further, as the downward trend present among those who use the internet to make financial decisions is also (unfortunately) consistent with this type of selection bias, and not accounting for this selection bias could lead to erroneously concluding that both financial planners are adding value (when perhaps they are not) and that transactional advisors are harming clients (when perhaps they are not). It’s reasonable to suspect that more nuance exists here in both directions—e.g., both financial planners and transactional advisors can either positively or negatively influence a client’s situation, although quite likely not at equal rates. Nonetheless, Blanchett’s study does provide some potential preliminary evidence that financial planners may have a positive impact on households and adds to a steadily building literature on the value that financial advisors provide.

Influence of Financial Planner Use on Holding Municipal Bonds

Continuing with the theme of financial decision-making among those who use a financial planner, a paper from Timothy Todd, Maurice MacDonald, and Stuart Heckman, titled Examining the Conventional Wisdom of Municipal Bond Investments and Use in Financial Planning examined whether any relationship exists between the use of a financial planner and holding municipal bonds.

While the conventional wisdom regarding municipal bonds is that they can be effective tools for individuals with high income for the purposes of reducing tax liabilities, little empirical evidence exists in the financial planning literature regarding precisely who does tend to use such investments. Furthermore, given the complexity of understanding tax-efficient investing (which requires not just an understanding of tax implications of certain investments, but also the underlying investment opportunity itself), a higher usage rate of municipal bonds among advisor-assisted individuals could be an tangible piece of evidence supporting the value that a financial advisor can provide (assuming, of course, that municipal bonds are appropriate for such individuals).

Todd et al. use the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to explore these questions. Because this data set includes detailed information regarding not only the assets and liabilities of individuals but also attitudinal and other demographic characteristics, the authors were able to assess what factors were associated with holding municipal bonds.

Not surprisingly, those with higher levels of net worth and investment income were more likely to use municipal bonds. However, forms of active and passive income were not associated with the use of municipal bonds, despite the fact that these forms of income still influence an individual’s marginal tax rate, and therefore would presumably be positively associated with municipal bond use as well. The authors also found that willingness to take financial risk was negatively associated with the use of municipal bonds, some measures of objective financial knowledge were positively associated with the use of municipal bonds, and subjective financial knowledge (i.e., a self-assessment of one’s financial knowledge) was not associated with the use of municipal bonds.

Regarding the use of financial professionals, Todd et al. found that those who use a financial planner or an accountant were more likely to hold municipal bonds, even after controlling for other factors such as age, gender, income, and net worth. The authors note that this finding is interesting, as it may be evidence of a potential recommendation effect that would help demonstrate the value of a financial advisor.

However, consistent with the caveats noted by Blanchett in his use of the SCF (see article above), the authors do note that a limitation of this study is that any relevant-but-omitted variables which could not be included in this analysis could influence the results. An unfortunate reality of cross-sectional research such as this is simply that while we can identify that correlations between factors exist, we cannot determine whether one factor causes another factor. Ultimately, this is just a reality of research using this type of data, but again, Todd et al. document another potential piece of evidence pointing to the value that financial planners can provide.

Who is Victimized by Investment Fraud?

Again, sticking with the theme of consumer engagement with the financial industry, Steven Lee, Benjamin Cummings, and Jason Martin explore the characteristics of those who have been victims of investment fraud in their award-winning paper (Northwestern Mutual Best Paper Award in Insurance/Risk Management) titled, Victim Characteristics of Investment Fraud.

Based on a review of SEC disclosures of instances of fraud, the authors posit that five “fraud languages” (designed in a similar vein to Chapman’s five love languages) are commonly used by fraudsters against their victims. These languages include perceived success (e.g., false account statements that give a sense that all is going well), air of familiarity (e.g., using one’s identity as a member of a common group, such as a church, to build trust that can be exploited), claim to authority (e.g., appealing to the approval of some third-party institution, such as a bona fide business, as evidence of trustworthiness), noble pursuits (e.g., tying the fraud to the mission of some other institution, such as a non-profit organization or a church), and framed authenticity (e.g., similar to claim to authority, but applies specifically in cases where fraudsters attempt to build trust by pointing to their being regulated by some third-party governmental institution such as the SEC).

Using the 2008, 2010, and 2012 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) (a longitudinal survey of Americans over the age of 50), Lee et al. were able to identify individuals who had self-reported being victims of investment fraud within the past five years. Using principal components analysis (PCA) (a statistical technique for reducing a large number of variables into a smaller number of "components," which are subsequently often named by researchers to reflect what it appears the overall component may be measuring), the researchers identified five factors that they referred to as (1) control and certainty, (2) long-term orientation, (3) responsible spending, (4) save for heirs, and (5) investing confidence.

While some may associate investment fraud with elder abuse and other forms of victimization that prey on particularly vulnerable populations, Lee et al. found that it is actually younger (among a sample of individuals age 50+), wealthier, well-educated males that disproportionately reported being defrauded within the past five years. Furthermore, using a logistic regression analysis that included the factors identified via PCA, the authors found that individuals who exhibited responsible spending were less likely to report being defrauded within the past five years.

While the authors could not directly test the fraud languages developed within their study, they were able to identify some other notable characteristics which may help provide a clearer understanding of who is most at risk of being victimized by financial fraud.

Overall, the second Academic Research Colloquium again brought together a strong mix of academics and practitioners to present and discuss financial planning research. It will be interesting to see how the ARC continues to evolve in coming years, as the Center for Financial Planning faces both challenges and opportunities such as the continued pursuit of developing a high-impact journal (Financial Planning Review) that is attractive enough to get scholars to submit their best work, dealing with the (potentially) declining sponsorship and institutional support for the event, and the Center’s ongoing push to establish the ARC as the core “academic home” for financial planning research. Only time will tell if the Center for Financial Planning will be successful in their pursuit, but the ARC continues to be a conference worthy of attending for both academics and practitioners who wish to engage in academic research.

So what do you think? Did you attend the 2019 Academic Research Colloquium? Do you have plans to attend in the future? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Leave a Reply