Executive Summary

After almost a year of often-public discussions, the CFP Board recently delivered its decision to financial planner Rick Kahler that, because he owns a (commission-based) real estate brokerage firm to which his financial planning clients are sometimes referred, he will no longer be permitted to label himself as "fee-only" and must describe his compensation as "commission and fee" instead, in light of the commission-based related party. In response, Kahler has declared that he will likely drop his CFP certification (after being the first in South Dakota to earn the CFP certification over 30 years ago), and may even file a lawsuit with the CFP Board over the issue, after failing to find any other remedy to the situation in more than 10 months of talks with CFP Board staffers.

In point of fact, though, the CFP Board's "related party" rules were arguably designed to catch situations precisely like Kahler's - the whole point of the rule is that a planning firm cannot make itself "fee-only" by simply splitting off its commission-based work into a separate business still owned by the CFP certificant. To allow such behavior would render compensation disclosure meaningless, as all advisors could be both "fee-only" AND "commission-only" by just hanging two shingles! As a result, it appears that this time the CFP Board may have really gotten its ruling right in this case.

However, the reality that the CFP Board could not come to an amicable resolution with Kahler about how to unwind the situation highlights what is still the CFP Board's fundamentally flawed interpretation of its own compensation disclosure rules. Kahler offered to cease providing referrals to the real estate firm, or even to outright bar any of his financial planning clients from doing business with the real estate firm, yet the CFP Board still insists that the mere fact that he owns the private-held firm "taints" his fee-only status, and that even if Kahler can prove that 100% of his clients pay only 100% fees from this day forward, forever, Kahler is still required to "disclose" client commissions that wouldn't actually exist or face potential sanction.

Instead, the CFP Board insists that the only solution is for Kahler to divest himself of his non-majority stake in a family firm he has owned for over 40 years, for what would surely be a significant personal financial loss to Kahler in trying to sell an illiquid closely-held business. But should the CFP Board really be allowed to dictate to fee-only CFP certificants what are and are not "permissible" investments to own for personal investment purposes apart from their financial planning clients? Ultimately, Kahler's dilemma about how to come back into compliance with the fee-only rules - and his inability to do so without divesting himself of a family business that he is willing to legitimately run separate from his financial planning clients - emphasizes the continued absurdity of how the CFP Board is interpreting its own three bucket doctrine for determining compensation to disclose.

Michael's Note: On July 29th, the day after the publication of this article, the CFP Board and Rick Kahler have issued the following joint statement: "CFP Board and Rick Kahler, CFP® continue to have ongoing conversations in which CFP Board is providing Mr. Kahler with guidance about how to properly identify his compensation. Until CFP Board provides the guidance Mr. Kahler has requested, CFP Board will not take any disciplinary action related to identification of his compensation."

Understanding The Kahler Situation

Rick Kahler is a long-standing CFP certificant who first got his CFP marks in 1983 (and was the first in South Dakota). Over his career, he has been involved in both a family real estate business (since 1972) and his advisory practice (founded in 1981), though in recent years his efforts have been focused primarily in his advisory firm, Kahler Financial Group.

While Kahler is not involved in selling real estate or the day-to-day management of the real estate brokerage business, he does still own a 50% stake in the family firm with his brother, and the business is an entity that is compensated by commissions (as is common for real estate brokerage). Since his advisory firm does not directly accept any real estate, insurance or securities-related commissions, Kahler refers to his business as “fee only”, and has also been an active member of NAPFA (which affirmed his “fee-only” status under their approval process as well).

However, last year the CFP Board ruling on Alan Goldfarb came out, followed shortly thereafter by the announcement of the lawsuit with the Camardas (and that Goldfarb was just the tip of the iceberg!), and the CFP Board publicly stated and embraced its “new” view (which had never been ruled upon in this manner before) that the mere ownership of a commission-paying entity is sufficient to require a CFP certificant to state that he/she is compensated with “commissions and fees” (and not as “fee-only”) regardless of whether any clients even do business with the entity. After the CFP Board sent a notice to CFP certificants “clarifying” these rules last year, Kahler realized that his ownership of the real estate business could run afoul of the CFP Board’s position, both due to his ownership interest, and the fact that clients of the advisory firm actually are sometimes referred to the family-owned real estate business (Kahler states that his policy when asked for a real estate broker referral is to give the client the names of three firms in the area, one of which is his family-owned firm).

Given the potential issue, Kahler voluntarily approached the CFP Board with his concern that he might be out of compliance with the “new” policy. And for much of the past year, Kahler has been engaged with the CFP Board regarding his compensation disclosure, whether he can declare himself to be “fee-only”, and if not (due to his ownership and relationship to the family real estate business) what he can do to remedy the situation and maintain his status as fee-only – recognizing that the “forced” sale of a non-majority interest in a family-owned business could have significant financial ramifications on its value as a personal asset.

After approximately 10 months of conversations, during which Kahler has also been vocal in the industry media regarding his situation and the problem that it presents, the CFP Board recently announced its final decision to Kahler that his ownership and compensation arrangement do constitute a commission-and-fee structure, and that Kahler must cease marketing his business as “fee only” or risk being sanctioned by the CFP Board for a misleading compensation disclosure. In addition to this conclusion, Kahler indicates that his alternative proposals, including transferring his ownership interest of his family real estate business to his spouse or a blind trust, or agreeing to cease making any referral to any real estate brokerage firm when asked (including his own or any other), or even agreeing to bar any clients of his advisory firm from doing business with the real estate entity at all (so they truly operate “independently” of each other), were rebuffed by the CFP Board as not resolving the issue regarding his claims of being “fee-only”.

In light of the outcome, Kahler has now announced that he is considering whether he will renounce his CFP certification (so that he can continue to market himself as “fee-only” without risk of a public sanction from the CFP Board), and that he may sue the CFP Board regarding the matter and how the organization has handled the situation.

Evaluating The Kahler “Fee-Only” Situation

To me, the Kahler situation ultimately comes down to two important but separate issues: 1) Should Kahler have been allowed to define himself as “fee only”; and if not, 2) What should Kahler need to do/change to “rectify” the situation so he can call himself fee-only if he wishes to appropriately characterize his financial planning services that way?

Regarding the first matter, I have to admit that the CFP Board’s conclusion seems entirely appropriate, not merely because Kahler owned a real estate business, but because – by his own admission, and the disclosure on his own Form ADV – there were actual referrals of clients from the advisory firm to the family real estate business to which commissions were paid and Kahler received economic benefit (though Kahler indicates the amounts had been "negligible" in recent years).

In other words, Kahler really was in a position to refer an advisory client to a (related) business that would generate a commission that financially benefitted him as a material owner of both firms. Whether the real estate business shared the commission directly, paid out as a dividend, or merely accrued it as profit on the books, the fact remains that a business Kahler owned was being enriched by commissions being paid by clients of Kahler’s advisory firm. Arguably, the whole point of these related party rules was specifically to ensure that situations like this are recognized as being commission-and-fee, and that advisors cannot turn a commission-and-fee business into a “fee-only” firm but simply creating a separate-but-related-and-co-owned entity to gather all the commission income that flows back to the same person.

Of course, the most common such situation is a separate business that collects insurance commissions – as was the issue in Camarda – and not real estate commissions, but it’s difficult to see why they would be treated differently. Real estate is still a financially-related business, other forms of real estate commissions (e.g., from the sale of REITs) are clearly commissions, and the real estate business was viewed as being material enough of a relationship that it was disclosed on the Form ADV in the first place. If the related party was related enough (and the commissions it generates were material enough) to be disclosed on the ADV, the “commission and fee” compensation should have been the required disclosure for Kahler as a CFP certificant, too. As the CFP Board correctly concluded in their decision.

No Way Out From Related Party Ownership

On the other hand, the more problematic issue was that Kahler’s proposals to resolve the issue, including transferring ownership (albeit to other “related” parties), and especially the offer to just completely bar clients from doing business with both entities, was not sufficient to rectify the issue. Arguably, as long as Kahler was going to continue referring clients to the real estate business, and he – or a party/entity clearly related to him – was going to continue to be enriched by the commission compensation the client paid, the compensation disclosure should still have been “commission and fee”.

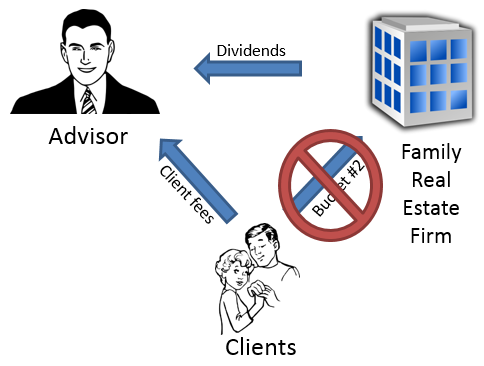

However, if Kahler was willing to actually create a total prohibition that would limit clients of the advisory firm from doing business with the real estate business – truly rendering the two businesses independent and unrelated with respect to clients – then why would the CFP Board still require Kahler to declare his advisory firm to be “commission and fee”? At that point, it would no longer be possible for that client to actually pay a commission, directly or indirectly, to Kahler or his businesses, in any way, shape, or form! Kahler would be required to disclose commissions that literally wouldn’t exist, as shown below!

Granted, Kahler would still own the real estate business conducting real estate transactions with other people where commissions occur (and generate dividends back to Kahler as the owner)… but that’s also true of any advisor who owns a financial interest in a private business, or a public one like the companies in the S&P 500. Advisors aren’t required to report to their clients the commissions paid by unrelated non-clients to unrelated businesses just because it’s a public or private stock that happens to be in their personal portfolio… so if Kahler was willing to create the same relationship with his own family real estate business, why was that still not acceptable… beyond the CFP Board’s ongoing arbitrary and problematic view that the mere ownership of commission-based businesses, even if unrelated to any actual client work, can still “taint” the fee-only status of an advisory firm that is otherwise fee-only in the business it actually conducts with clients. And being able to prove that 100% of financial planning clients paid only 100% in fees, ever, to anyone, is still not a legitimate defense to claim that the advisor is “fee-only” under the CFP Board’s rules!

Is it really appropriate for the CFP Board to have the right to dictate the private ownership of a CFP certificant’s stock portfolio and investments in companies unrelated to their actual financial planning clients? In Kahler’s situation, the CFP Board’s response was that the only way Kahler could possibly remain “fee-only”, regardless of whether his financial planning clients were barred from the real estate firm, was to actually fully divest his stock ownership!?

Ongoing Problems With The CFP Board Three Bucket Rule

As noted earlier, while I believe the immediate conclusion of the CFP Board regarding Kahler’s situation was right – clients of the advisory firm really were being referred to a related entity for financial transactions that resulted in commissions providing a financial benefit for the CFP certificant – the CFP Board’s inability to come to an amicable resolution for the situation with Kahler highlights the significant ongoing flaws that remain in how the CFP Board applies its fee-only definition, as well as the related definitions of the key terms that are used to apply the rules.

For instance, as the Kahler case highlights – and Kahler himself expresses in frustration after having requested clarification for months – there is still no clear definition of what constitutes “ownership” for the purpose of determining a related party. For instance, does spousal ownership actually count, or not? What about the use of a [blind] trust? There are cases to be made for allowing or disallowing either, but the CFP Board should have a clear and public position on this so CFP certificants understand the rules, and don’t find themselves in the position of being forced to divest ownership of illiquid assets on short notice.

Similarly, there is still no definition of “related party” in the first place, what constitutes a “related party”, and how significant of an ownership stake is required. Notably, the lack of definition on what constitutes a “related party” was a key factor in the Goldfarb case – where a mere 1% interest that paid a $2,000/year dividend was a fee-only “taint”, even though many advisors receive far more than this from the financial services stocks in their own investment portfolios. Of course, Goldfarb’s stock was a smaller, privately held company, and not a publicly traded stock on the S&P 500… but surely the CFP Board’s definition of “related party” is not going to hinge on whether a company has decided to do a public markets IPO, right?! In addition, the CFP Board’s rules for “fee-only” state that only compensation “from [the CFP certificant’s] client work” is supposed to count, yet the CFP Board is now stating that a party is related due to mere ownership even if there is no work actually done for clients (as would be the case if Kahler barred advisory clients from his real estate business, and just as Goldfarb’s advisory clients were not actually doing business with his 1%-owned broker-dealer, either).

Furthermore, the CFP Board has still not defined what constitutes “non-trivial economic benefit” from a related party, a factor that seems poorly considered in the Goldfarb case, may be a potential factor in the Kahler situation, and is possibly an issue in the Camarda scenario as well. Does “non-trivial” mean the compensation has to constitute a certain portion of the advisor’s income? Or a certain portion of the business’s? Does the related party entity have to be profitable, or does materiality depend on just the revenue provided to the business? If a client pays a $5,000 commission to a business that has $10,000 in expenses (so the business has a loss) and the advisor makes $600,000/year, is the compensation trivial because it’s <1% of the advisor’s income, trivial because the business shows a loss, or non-trivial because $5,000 is still a big chunk of change for the client themselves? Right now, the only way an advisor will know is after the fact, when they’re found guilty and publicly admonished for being in the wrong, because there is no definition and no bright line safe harbor. Or worse, is it only a matter of time before fee-only financial planners owning shares of an S&P 500 index fund risk being sanctioned by the CFP Board for claiming to be fee-only when they are really "commission and fee" because they own shares of commission-based financial services stocks within the index funds in their portfolio? Such an outcome may sound absurd, but it is exactly what is prescribed by a strict application of the current precedent for the CFP Board's flawed interpretation of its rules, when there is no clear threshold about what percentage of a firm is "too small" and what amount of income is "too little" to actually be trivial or not. Remember, Goldfarb received a public sanction for failing to disclose commissions that his clients never actually paid, simply because he had a 1% ownership interest that generated a $2,000 annual dividend. That's it.

The Kahler situation also highlights the confusion about what types of “income” even count as commissions in the first place. Kahler clearly thought that “commissions” should refer to insurance and securities/investment commission, and not real estate commissions. While I have sympathy for the CFP Board’s viewpoint that real estate commissions probably should be included, it still raises the question of where to draw the line. Would a store that sold furniture for the client’s house also count? If any commission-based entity or income can run afoul of the rules, does that mean an advisor must disclose themselves as “commission and fee” for also holding a Tupperware party for clients?!

But as I’ve written times before, the most fundamentally flawed aspect of the CFP Board’s definition is its failed "three buckets" approach to identify compensation, when an advisor must disclose “commissions” because the advisor owns a commission-based entity that no clients ever actually do business with in the first place. If Kahler really could show going forward that no advisor client ever does business with the real estate entity again, being able to prove that 100% of clients have only ever paid 100% fees is still not a legitimate defense to claiming that he is fee-only, merely because he still owns what at that point really would/should be an unrelated party!

After all, the technical definition from the CFP Board is that the advisor cannot be fee-only unless “all compensation from his/her client work comes exclusively from the clients in the form of... fees” (emphasis mine) yet if none of Kahler’s financial planning clients actually do any work with the real estate entity, how can Kahler receive compensation for client work!? How can Kahler be compensated by financial planning clients who didn’t actually receive services, and how can he disclose commissions that wouldn’t actually exist?

Of course, the reality is that there may still be other people who could receive services with the real estate business, but if they work solely with the real estate business, they would not be financial planning clients in the first place, as the CFP Board has taken pains in recent years to emphasize that financial planning has a limited scope and that a financial planning relationship (and therefore, associated compensation disclosure requirements?) only exists when the advisor does a financial plan or provides material elements of financial planning. So if clients of the real estate firm don’t get financial planning, and Kahler was willing to restructure his practice so financial planning clients really wouldn’t work with the real estate firm at all… why exactly would Kahler still be required to describe his compensation for financial planning work as “commission and fee” where there really would be no work done for his financial planning clients from his commission-based entity?

In fact, when the CFP Board eliminated its salary compensation category from its own "Find a Professional" tool last year, it did so with the specific explanation "...salary does not provide an accurate and understandable description of the compensation arrangement being offered by a CFP® professional because it does not describe how the client will pay the CFP professional and any related party." (emphasis mine) So if the CFP Board had the power to eliminate the "salary" compensation category altogether, and declare that compensation disclosure should be based on "how the client will pay the CFP professional and any related party" (not just how a firm compensates the advisor in the absence of what the client actually pays), then why can't the CFP Board apply the same clarifications of their problematic interpretation of the "3 bucket" approach?

Where Does The CFP Board Go From Here?

Ultimately, I will admit that I am still hopeful the CFP Board will “come to its senses”, clarify its key definitions, and resolve the flaw in its three-bucket rule by recognizing that client work must be delivered before a party is related, and that commissions must actually be paid and exist before they need to be disclosed. Unfortunately, though, given that the CFP Board is already embroiled in a lawsuit with the Camardas, it’s not clear that the situation will be resolved any time soon, as the court case could take years to complete – though notably, clarifying these rules, particularly regarding related parties, would not necessarily impact the Camarda case at all, as in that scenario there really were clients receiving services from a related party and paying commissions to it.

And sadly, the reality is that the CFP Board really could fix its rules any time it wants to, because the problem is not actually with the rules as they are written. The problem is that the CFP Board either has refused to define the key words in those rules – leaving ambiguity and confusion – or worse has taken a nonsensical interpretation of the words in those rules, such as claiming the rules require advisors to disclose commissions that don’t actually exist in the first place from a “related” party that has no actual relationship to the client because no client work was rendered. Fixing the situation is not about rewriting the rules, but simply reinterpreting them (perhaps with the assistance of Merriam-Webster!). The “change” that kicked off this series of problems was a faulty judicial interpretation of the rules by the inexperienced ad-hoc disciplinary committee established to rule on the Goldfarb case, which set a flawed precedent that has sent the CFP Board down a problematic path. And the “change” to fix it is issuing a clarification to the words in the current definition, that recognizes the interpretation of the words in the prior precedent were faulty. And since these issues are unrelated to the actual key factors in the Camarda case, the resolution really does not need to wait for the Camarda case to end, however many years down the road that may be.

In the meantime, Kahler sadly really is “stuck” and will have to either stop being a CFP certificant, or truly stop calling himself fee-only (even if he otherwise takes steps to completely separate his real estate commission activity). Though it’s worth noting that if Kahler renounces his CFP certification, after 90 days he will be required to pay a $100 reinstatement fee, after more than 1 year he will have to make up for all his missed CE along the way, and after 5 years he will have to sit for the CFP comprehensive exam again (or actually for the first time, since Kahler earned his certification before the comprehensive exam was instituted in 1991). By contrast, if Kahler merely recharacterizes his compensation as commission and fee “for now”, he can at least go back to fee-only in the future if/when the rest of the issues are resolved (and in the meantime, perhaps, he can simply state to his clients that he “receives no commissions from insurance and investment products” which remains accurate but does not use the prohibited “fee-only” label). And on the other hand, as I’ve written in the past, I’m not certain that using fee-only as the centerpiece of an advisor’s marketing is necessarily a good idea anyway?!

As for whether Kahler will sue the CFP Board over the matter, I have to admit that I hope this does not happen. Though I’m no attorney, I’ll admit it’s ultimately not clear to me on what grounds Kahler actually would sue; notably, while the Camarda lawsuit also ties back to fee-only compensation disclosures, the crux of the lawsuit is how their case was handled before the Disciplinary and Ethics Commission, not the actual definition of fee-only itself. And in the end, as noted here, it still appears to me that the CFP Board’s conclusion – that Kahler should disclose commissions that actual financial planning clients are paying to an actual related party that Kahler owns – actually is a proper application of the rules.

On the other hand, if Kahler really does bar his clients from doing business with the real estate entity, establishes documentation that 100% of his clients really did pay only 100% in fees and no commissions to any (related) entity, holds himself out as fee-only, and then really does get sanctioned for it, he may have some grounds for claiming that the CFP Board’s Disciplinary and Ethics Commission is ignoring the plain English language of its own rules. Though to say the least, that would be a rather public and messy (and potentially expensive) fight for Kahler.

Whether it comes from Kahler or someone else, though, it seems clear that until the CFP Board does a better job with its definitions, and fixes the flawed application of the three bucket rule, the problems will just continue to accrue. While the organization has maintained throughout that its position on compensation definitions is not “new” and that everything is “clear”, if that were the case the CFP Board would not have had to:

- Ask for the resignation and then publicly sanction its own board chair (Goldfarb) for failing to comply with the compensation definitions

- Remove two members of its own Disciplinary and Ethics Commission for also failing to following the definitions

- Eliminate its own compensation definition of salary from its "Find a CFP Professional" search engine after acknowledging it doesn't reflect what clients actually pay (yet refusing to hold the definition of commission compensation to the same standard)

- Issue a standalone notice to members specifically to explain the rules again

- Produce a new 1-hour webinar further explaining the “already clear” rules

- Reset compensation definitions for all "fee-only" advisors and issue yet another notice to "clarify" the rules after facing an article in Financial Planning magazine and WSJ about 468 wirehouse brokers - and apparently thousands of others not studied by the media - who even after all of the above, including the educational outreach, were still not applying the compensation disclosure rules appropriately and had to be granted retroactive amnesty (and even though the issue had been pointed out months earlier on this blog as well)

- Put NAPFA in the position where the current rules are so unusual that as much as 5% of their own membership doesn't qualify, and forced them to redefine their rules to match the CFP Board, despite NAPFA’s role they have played in defining this very term for 30 years

- Put certificants like Rick Kahler in a position of divesting the interest in an illiquid non-majority interest in a privately held company while failing to provide clarity about the definitions that could give ANY other way to remedy the situation

- Continue to face public and private criticism from industry leaders about a lack of clarity of the rules, including the fact that the CFP Board's current rules render all their commission-only advisors at brokerage firms in the exact same rule violation as fee-only advisors at the same firms (the next shoe to drop?)!

And then, of course, there’s the fact that the CFP Board is in an ongoing lawsuit about the definitions and its process for enforcing them (though ironically, the rules may actually have been clear and properly applied in that particular situation!).

To say the least, this is not a list of outcomes from rules that are “clear” and able to be properly enforced, despite the CFP Board’s public insistence to the contrary. Hopefully the CFP Board will come to its senses before some real damage is done.

Michael, excellent post, as always. Please permit me to add a few observations.

First, I believe “fee-only” is an important term, and the definition of that term must be preserved, and not co-opted. Being “fee-only” in financial services means not receiving material compensation from product providers, and this avoids many of the conflicts of interest which pervade financial services.

Second, while I have friends and colleagues that run RIA firms, with as associated insurance agency firm. For several colleagues they view this as a means to provide clients with lower-cost solutions, and they provide mostly term life insurance and long-term care insurance to clients, often by rebating (but not “rebating” under the law) by offsetting investment advisory fees. Offsets to investment advisory fees are a common practice in fiduciary environments (e.g., bank trustees using proprietary funds). Still, a few colleagues use the insurance firms to sell permanent life insurance, in my view when no permanent need exists. In either case, have any interest in an insurance agency negates, in my view, the ability to use the term “fee-only.” Not only would it violate CFP Board’s rules, but it would also be misrepresentation under state common law and under Sect. 204 of the Advisers Act.

Third, Rick Kahler is known to me, and to many, many others, as a thoughtful and thoroughly honest man. As increased focus has been brought to bear on “fee-only” definition, and new questions have emerged, I respect his attempts to proactively reach out to both NAPFA and the CFP Board to seek guidance and to comply with the fee-only definition.

Fourth, the receipt of only dividends from an ownership interest (or capital gains, or any other return) from a commission-based entity in the broad field of financial services (which includes insurance sales, broker-dealer, mortgage lending, and – likely – real estate brokerage), is likely to occur for all of us. I own a selection of mutual funds, which in turn own 10,000+ stocks globally. It is possible, as my mutual funds are largely market-cap-weighted, that some huge financial services firm (Citicorp, GE – which has financial services units?) might exceed 1% of my total portfolio, as a result – although I have never checked on same. Hence, there must be some de minimus exception. For years, NAPFA defined de minimus by its 5% test, but has since moved toward just a practical application of a de minimus standard. I hope the CFP Board is doing the same.

Fifth, the reason behind prohibiting material ownership of a related company, by a fee-only financial planner, is to remove the mere temptation (even unconciously) to usurp the client’s best interests. Many a jurist has warned about the “subconcious” motivations which arise when conflicts of interest exist. Hence, “fee-only” could be regarded as the purist form of compliance with the old adage, “no man can serve two masters.”

Sixth, the problem of spousal ownership of a company is a difficult one to resolve. What if a fee-only financial advisor has a spouse which works in a bank, and the bank owns (as many do) either a broker-dealer or insurance agency interest, and/or sells its own funds (for commissions and/or 12b-1 fees)? Does this mean that the fee-only advisor cannot hold out as such? Does it matter what the spouse does in the bank – i.e., teller, versus branch manager, versus commercial loan officer, versus private client relationship manager? Does it matter that the spouse may receive bonuses for referrals of clients to other areas of the bank? Where does this begin, and where does it stop? At the same time, I have seen a fiduciary (an attorney, involved in estate planning) who made referrals to her spouse (an insurance agent and registered representative) all the time, for products to implement ILITs, etc. – this seems to be a far more certain attempt to circumvent the spirit of the fiduciary rule to keep the best interests paramount at all times, and to properly manage conflicts of interest (even after disclosure) to ensure that the client is never harmed as a result of the conflict. (A related issue is whether the CFP Board can extend its rules to cover ownership by a spouse, or a spouse working in, an entity which receives commission-based compensation. This requires a legal interpretation of the CFP Board’s rules, which is a more complex issue.)

Seventh, Rick’s idea to prohibit referrals from his financial services firm to his family’s real estate firm seemed a plausible solution. Such “brick walls” often existed (at least in the past) as a means of adhering to fiduciary obligations in diverse financial services firms. And, in my mind, the solution adheres to the spirit of one’s fiduciary obligations and the spirit of the term “fee-only.” Enforcement could occur by means of a disclosure in Form ADV Part 2A of this arrangement (so that clients would be put on notice that they would never be referred), as well as some sort of annual affidavit Rick (or someone in his firm) would sign attesting to compliance with this brick wall. I hope that the CFP Board revisits this potential solution. This solution avoids the conflicts of interest, and respects, in my view, the spirit of the term “fee-only.”

Lastly, I would encourage your readers to not utilize the term “fee-based.” The CFP Board does not use this term, wisely. The term “fee-based,” as it omits mentioning of commissions, is inherently misleading. The correct term is either “fee-and-commission based” or “commission-and-fee based” (determined by dominance of the type of fees received). I would like to see the CFP Board, as well as federal and state regulators, take a stand on the misleading effect of the term “fee-based,” as violative of Sect. 204 of the Advisers Act and as common law fraud.

I think it is a bit of a stretch to declare the use of “fee-based” as common law fraud. In some cases, perhaps, but it isn’t that straightforward of an issue. Particularly when we consider the advisors who don’t receive any commissions and wouldn’t be fraudulently describing their business as fee-only (even if industry organizations/regulations wouldn’t condone the use). I can think of many examples where the use of fee-based wouldn’t fit any of the criteria for fraudulent behavior (http://www.mitchell-attorneys.com/legal-articles/common-law-fraud/).

Ron,

Thanks for the comments. A few key issues here:

1) I agree with you about the importance of being clear on the fee-only term. Owning an RIA and an insurance agency where clients cross over is NOT fee-only. I do not believe Kahler’s arrangement was fee-only either, as I stated here. The issue is that even if NO clients EVER did ANY business with the commission-based entity, ever, and EVERY client paid ONLY 100% fees, and that can be proven, IT IS STILL A VIOLATION TO CALL YOURSELF FEE-ONLY under CFP Board rules. THAT is a problem. When being able to prove that 100% of clients pay 100% fees and zero commissions ever is STILL not a defense to claiming you are fee-only, there is a problem.

2) While you articulate the value and importance of a de minimis rule, recognize that the CFP Board DOES NOT HAVE ONE. This is a key point I have emphasized repeatedly. There is NO safe harbor, no de minimis. In fact, under CFP Board pressure, NAPFA has now eliminated THEIR 2% de minimis threshold, creating the same problem for NAPFA. Technically, your mutual fund ownership really IS a violation, and the only defense is to plea to the DEC that should ownership should be “too little to matter”. Alan Goldfarb’s ownership interest was 1%, and generated a $2,000 dividend, and that was still “too much”, so the question of “what is de minimis” is REALLY an issue here!

3) Similarly, I agree with you about the spousal (or other family ownership) concerns. They’re legitimate concerns. There aren’t easy answers to many of the issues. However, the CFP Board’s current “we won’t give you ANY guidance, we’ll just punish you after the fact if we decide you’re in the wrong” is not a reasonable approach to enforcement.

4) I agree with you about the acceptableness of a “brick wall” solution. But recognize that NO brick wall solution is EVER permitted under CFP Board rules, because mere ownership – EVEN IN THE ABSENCE OF ANY CLIENT EVER DOING BUSINESS WITH THE FIRM AND NO COMMISSIONS EVER BEING PAID – is STILL a violation. That’s my whole point here.

5) Regarding “fee-based”, given that it is not an accepted compensation disclosure under CFP Board rules, I don’t endorse it all for any CFP certificants. Which is also why I didn’t even raise it as a possibility in the discussion here.

Thanks for your comments!

Respectfully,

– Michael

Michael, thank you for continuing to be a voice of reason in the midst of this idiocy! Have to say, though, I’m very sad that I’ll have to give-up my Tupperware parties. 😀

Larry,

Thanks for the kind words.

Alas, I wish we could see FPA and NAPFA take an advocacy leadership position on this though!

– Michael

Micheal,

I would like to add my thanks for your efforts to bring reason to this issue. If I may, though, I would like to re-frame the issue slightly. you repeatedly use terms like “in reality” and “really” and I wonder if that is not really the crux of the issue here. In an almost FINRAesque way (never a complement coming from me) the CFP Board has taken the position that only their rules matter and the truth is simply not relevant.

Instead of taking a principles based approach that clients ought never to be mislead by any claim of being “fee only”, which I think we could all heartily agree with and support, instead of focusing on the client as being paramount, they have chosen to focus on their rules as being paramount. As you point out, the fact that no client was ever given conflicted advice in the Goldfarb situation was simply deemed irrelevant.

The fact that Kahler offered a mechanism that would make it impossible for any client to be given conflicted advice is also deemed irrelevant. But that is exactly where the CFP Board got it backwards — whether clients are being mislead, whether clients are being given conflicted advice ought to be the ONLY thing that is ultimately relevant. Yet instead of focusing on protecting the clients and the public form conflicted advice, they have chosen to make the issue solely one of adherence to their rules – period.

Rule infractions seem to be the only thing that matters to the CFP Board. That’s wrong. The truth ought not to be irrelevant. Whether the clients’ and the public are IN FACT being given conflicted advice ought not to be irrelevant. Those are the rationales for the rules. In the final analysis, they ought to be the only things that matter. The rest is mere ego.

Would not just doing away with AUM fees and commissions be the solution to this problem? Has anyone heard of sending a bill for services rendered and then getting paid by check, money order, cashier’s check, credit card or ACH work? This would solve many, many, many problems in this conflict of interest ridden business of handling people’s lifelong, hard-earned savings. It seems absolutely ridiculous to me that there are payments like this–AUM fees and commissions–when the service deals with something that people have sacrificed and labored for so long to accumulate–their lifelong, hard-earned savings. Payments should NOT be out of sight, out of mind; payments should be front and center and in the bright, noon sunshine–no clouds, no fog, no darkness.

I don’t think there is anything inherently wrong with commissions or fees; I think the issue, as you pointed out, is the ways advisors can legally be deceptive in their pricing. Burying fee disclosure in piles of documents should be fraud, but instead, it has been legalized through the regulatory system.

Fees and commissions are for widgets NOT for people’s lifelong, hard-earned savings, and we’re not just talking about one person’s money. We’re talking about millions of people’s money. I’d like to say that I think that people are born with and maintain oodles of integrity, but let’s get real here folks. Your industry attracts many bad characters who lack morals. Your industry does not attract Mother Teresa’s. And Mother Teresa’s are the kind of people that should be managing people’s lifelong, hard-earned savings. All that money is like a magnet for the corruption and greed. Think–The best way to rob a bank is to own one? The second best way is to be a so-called financial advisor and get paid via AUM fees or commission or a combination of both. Anytime a so-called financial advisor’s name is mentioned in industry news it is followed by his/her AUM. How sick is that? It feeds/breeds dishonesty and greed and a keep-up-with-the-Jones mental state. Suffice it to say, if people from the outside were reading your industry’s publications and understood how your industry operates, no one would give you their money. There’s an undertone of entitlement in your industry. You are NOT gods although you do remind me of televangelists. Give me, give me, give me. Many of you are about as far from a god as one can get — https://screen.yahoo.com/church-chat-satan-000000502.html

Mother Teresa accepted stolen money from Fraudster Charles Keating. She declined to be return the money to the rightful owners after being notified they were a result of criminal activities. Instead she wrote a letter asking the court for leniency for the Keating. Should her types really be managing our hard earned money? The god industry breeds the same dishonesty and greed as the financial industry.

Do you think that Mother Teresa wrote that letter or a bunch of lawyers

that worked for the Vatican that were trying to protect that Catholic

Church? I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again the financial

“services” industry reminds me of the tobacco industry, the

Catholic Church and the NFL. All are leagues full of denial and

non-transparency.

I doubt that Mother Teresa bought a yacht with that money, but someone at the Vatican may have. What do you think?

I used to recommend to my non-FA clients that they only hire a CFP, not because they are fee based, but more because of the certification process and the training that needs to take place yearly to keep it.

I stopped doing that 2 years ago.

IMO, as the industry continues to change, more firms will offer clients more services under one roof. And so what if they earn a commission… as long as the commission is stated and known to the client.

There are many ways for FAs to be paid and many business models.

What matters or should matter, IMO, in any industry, is that nothing is ever sold to a client just because of a fee or commission someone is making. More than fees or commissions, people should take the time to really know clients, their needs, and goals and only offer/sell them services or products based on the information gathered.

IMO, that’s a heck more important that having a CFP designation or all the drama, that continues, regarding what percentage of other businesses FAs work with or own.

The integrity of the people we hire to work with us is more important, IMO, than whether a fee or commission is charged.

I think any kind of AUM fees should disqualify an advisor from advertising “fee-only”. An AUM fee is basically a commission in disguise. Investment management is a product and if you are “fee-only” you should not be selling any product other than the advice itself. Why is selling insurance or getting a commission for real-estate different than AUM on investments? I really don’t see the difference and I think the “fee-only” designation should be much narrower than it is. And that would really solve the problem.

As for the Kahler situation, I see the CFP board’s point. If he benefits from a commission-based business which he owns and refers or might refer clients to the business, then he can’t be fee-only. But I can’t understand that he would rather drop his CFP designation than simply change his advertising to say “fee-based”.

David,

I agree with your point regarding Kahler and the fact that clients were being referred. The issue here, though, is that even if clients hadn’t been referred, weren’t being referred, and they were never going to be referred, there was STILL no way for Kahler to be fee-only. Even if 100% of his clients really did only ever pay 100% of fees. Just because Kahler had a stock in his personal portfolio that happens to be a commission-based business.

– Michael

Michael,

I think it might be pretty hard to enforce that referral wall and that’s probably what the CFP board is struggling with. Does stock in your personal portfolio influence your recommendations? In politics I think the assumption is that it might. That’s the reason politicians put their personal holdings into blind trusts where someone else manages the investments. I am in favor of a much narrower interpretation of fee-only; not because I am fee-only myself, but because I am not. I’m very skeptical of the moral high-horse that fee-only planners seem to be on. I am not a fee only planner, but I still have the same fiduciary duty to my clients that the fee-only planners have.

So back to Mr. Kahler: Let’s say that his family’s real estate firm is really the best in town and the others are inferior. Mr. Kahler cannot refer his clients there, but as a fiduciary he really should be referring clients to the “best” real estate firm and that would be his family firm. That’s wrong too! The referral wall and fee-only label is stopping him from his fiduciary duty. Does this serve clients fairly?

Define fee-only very narrowly and most advisors would not qualify. I’m in favor of that. Fee-only planners would then REALLY be morally better.

Should all CFP’s divest themselves of any fund that holds financial services companies? After all, the S&P 500 holds Bank of America, Bank of NY Mellon, Citigroup, JPMorgan, PNC, SunTrust, US Bancorp, Wells Fargo, etc. All of these companies participate in and generate substantial revenue from commission-based activities in the financial services arena. Therefore, any CFP holding an S&P 500 index fund (or really any large cap fund) is profiting from commission-based business. Is sector-based investing is going to get very hot soon?… 🙂

I agree with Michael. The CFP is initially correct in determining that Kahler is not fee only. However, it’s puzzling that even though Kahler proposed to cease referring any of his financial advisory practice’s clients to his jointly owned real estate firm, the CFP board still said no to being fee only. In my opinion, Kahler’s offer seems like a reasonable solution that protects clients (what the CFP board wants) and what Kahler wants (ability to hold himself out as fee only). Normally I’m very strict with respect to fiduciary matters such as being fee only, but the CFP ruling seems a bit over the top by refusing Kahler’s resolution.