Executive Summary

Leveraging the success (and the systems and infrastructure) of tax-preferenced 529 college savings plans, in 2014 Congress passed the “Achieving a Better Life Experience” (ABLE) Act, which created a new “529A” version of the accounts, designed specifically to allow families to accumulate assets on a tax-preferenced basis for special needs beneficiaries. Which for some families may be a more cost-effective (and tax-favored) alternative to a special needs trust, and for others may at least supplement a special needs trust for a portion of the assets the family sets aside.

The caveat, however, is that similar to 529 college savings plans, the new ABLE accounts are established on a state-by-state basis, with everything from the costs to the state tax deductions varying from one state to the next. And because 529A plans are more likely to be used transactionally on an ongoing basis for their special needs beneficiaries… they’ll less likely to grow to a significant size. Which has resulted in some states deciding not to even offer the accounts. Making the process of selecting a 529A plan far more of a state-by-state evaluation effort than even traditional 529 college savings plans.

In this guest post, Andrew Komarow and Craig Breitsprecher of Tenpath Financial Group, an advisory firm with a specialization in working with families that have special needs beneficiaries, explores the current landscape of 529A plans, the key criteria to compare one ABLE account to the next, and what advisors should be mindful of in helping clients to select a plan. Including the fact that very few 529A plans are even designed to work with financial advisors directly in the first place, with only one broker-sold plan and no fee-based options. But with at least some potential workarounds for RIAs through their own custodial platforms.

And with potential legislation under consideration in Washington that might further increase contribution limits, expand age limits, and overall make 529A plans more appealing, ABLE accounts may increasingly need to become part of the financial advisor’s "quiver" of tools to use with clients. At a minimum, though, it’s important to be aware of the options that exist today, and what it takes to ensure that clients who do have a special needs beneficiary pick the plan that’s best for them.

As the advocacy of the special needs community continues to be a major focal point in financial planning, 529As, also known as ABLE accounts have become a tremendously useful tool for families in their care for a disabled person. The “Achieving a Better Life Experience Act” of 2014 created 529A accounts with the intention of allowing families to save and invest funds for the care of a disabled family member while maintaining eligibility for public benefits such as Social Security, Medicaid, and public housing.

In our practice, we work closely with respected attorneys and tax-advisors who have a hand in crafting a care plan for a family member with special needs. We are often asked to facilitate opening 529A accounts and better educate families on their use.

Understanding Section 529A Plans For Special Needs Beneficiaries

Perhaps the best way to become familiar with 529A accounts is to compare them with a 529 college savings plan for education.

Like “regular” 529 accounts for college, all growth inside of an ABLE account is tax-deferred, and the subsequent growth (whether from capital gains or dividends or ordinary income) can be withdrawn tax-free if used for qualified purposes. In the case of a regular 529 plan, “qualified expenses” for higher education under IRC Section 529(d)(3) include those incurred for tuition, supplies, or fees incurred by the institution. In the case of 529A plans, IRC Section 529A(e)(5) defines “qualified disability expenses” to include basic living expenses, health, housing, transportation, legal fees, assistive technology, and similar expenses, for the eligible (disabled) beneficiary. Distributions not made for qualified disability expenses from a 529A plan are taxed as ordinary income, and subject to an additional 10% penalty tax as well.

Notably, though, a key benefit of a 529A plan – as opposed to just saving money directly for a special needs beneficiary – is that the tax-free distributions for qualified disability expenses from the ABLE account are also not treated as “income” for the purposes of qualifying for most state or federal aid in the first place. In other words, 529A plan distributions are not only excluded from income for tax purposes with the IRS, but also for means-testing purposes with various state and federal aid agencies. Nor is the account balance of the 529A plan treated as a countable asset, either. Though for purposes of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which kicks in beyond traditional Social Security Disability Income benefits, 529A plan account balances above $100,000 are considered (and can trigger suspension of SSI benefits), and 529A plan distributions used specifically for housing expenses are treated as countable income for SSI (again potentially disqualifying some or all of the SSI benefits). In addition, under the new IRC Section 529A(f), any remaining funds in a 529A account at the death of the beneficiary must be used to repay the state for any Medicaid assistance received by the beneficiary after the account was created.

In order to be an eligible beneficiary of an ABLE account, the beneficiary must be someone who is blind or disabled, as certified by a physician, due to an impairment that began before the age of 26, and has lasted (or will last) for at least 12 months. Alternatively, an individual who is receiving Social Security disability payments (or aid from a state program funded by Social Security) is presumed to qualify (without the separate physician’s certification), but again only as long as their blindness or disability began before the age of 26. In addition, contributions are limited to only $15,000 per year for any individual beneficiary (i.e., the Federal annual gift limit).

In essence, then, a 529A plan functions similar to a special needs trust, in that it provides benefits for a special needs beneficiary but where income and assets can be excluded for (most or all) Federal and state aid purposes. However, ABLE accounts are unique in that their growth inside the plan is tax-free as well (while special needs trusts are still taxable trusts). Although in exchange for their more preferential tax and aid treatment, 529A plans have the aforementioned annual contribution limits and a $100,000 limit to still fully qualify for social services, and have a Medicaid payback requirement (unlike a special needs trust).

There are also some interesting interplays between the 529A plan and special needs trust strategies. For instance, one can use a special needs trust to contribute to an ABLE account itself; because one cannot use a special needs trust for shelter expenses, this may be a creative workaround. Another important practical consideration is the fact that, because income within a special needs trust is taxable, trustees may be reluctant to make investment changes after a period of time due to embedded capital gains, and/or may primarily/only invest into growth assets to avoid the unfavorable taxation of interest and dividends… none of which are issues with the (tax-deferred-and-ultimately-tax-free) ABLE account.

Functionally, it should also be noted that special needs trusts are often more of an estate planning tool, whereas a 529A plan is a more "current" independence-enhancement tool, due to the ability to add debit cards and other transaction privileges to the account to facilitate the direct and ongoing use of the account by a disabled beneficiary.

529A Plan Selection And State-By-State Variability

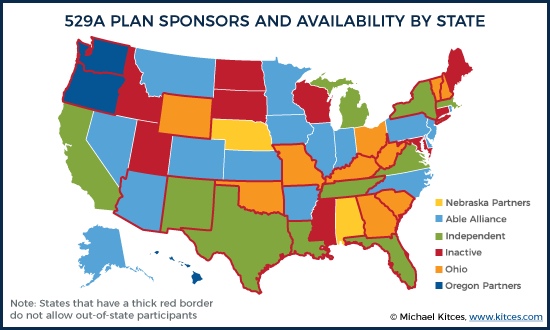

Similar to 529 college savings plans, 529A plans are also organized by state, with each state potentially offering its own 529A plan (or agreeing to cross-utilize another state’s plan for states that don’t want to roll out their own). And similar to 529 college savings plans, individuals can potentially choose any state’s 529A plan to participate in.

Currently, the available “independent” plans include Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Tennessee, and Virginia. In addition, several coalitions of states have formed, where sister states all participate in one anchor state’s plan; for instance, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, South Carolina, and Vermont are all partner states of the Ohio 529A STABLE Account plan, and a coalition of other states have come together in the “ABLE Alliance” to share expenses and lower the costs of 529A plans in their states (including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, DC, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island).

A meaningful recent addition to the independent plan is CalABLE. As the largest state in the U.S., California, has come to the forefront in launching a series of educational events, conferences, and lectures meant to better educate the public on policy and support (rather than just relying on ABLE account product to speak for itself in an otherwise complex planning area).

However, a key caveat of 529A plans is that, unlike their college-based brethren, when it comes to ABLE accounts, not all states have adopted plans (even if they have the legislative rules in place to allow them), including Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wisconsin. In addition, some states have chosen to limit themselves to only in-state participants. For instance, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming do not allow for out-of-state investors, regardless of whether the client’s own state of residence offers a plan. (Which means residents in a state that doesn’t offer a plan must then choose another state’s plan that will accept them as out-of-state investors!)

According to a progress report from Strategic Insight in December of 2017, the average ABLE account balance has grown from $1,000 in June 2016 to $3,679 in September of 2017. Of the roughly $48.5 million invested in ABLE’s, the independent plans hold 40% of assets, Ohio Partner States hold 35% of assets, ABLE Alliance States hold 12% of assets, with Nebraska, Alabama, Oregon, Washington, and Maryland comprising the remaining 12%.

Differences In 529A Plans From State To State

Ultimately, the reason why the state-by-state choice of 529A plan matters is that, similar to 529 college savings plans, everything from the costs to the tax treatment of ABLE accounts may vary from one state’s plan to the next.

The largest expenses for both 529 and 529A plans consists of their underlying investment management costs, and thus far, typical expense ratios appear to be fairly similar. Saving for College conducted a study of 529 fees which showed the average costs to be about 42 basis points per year, while the ABLE National Resource Center has found that the average fee for an ABLE account is around 38 basis points per year. In addition, though, ABLE accounts also typically have account maintenance fees – currently averaging around $45 per year – that are assessed annually, while traditional 529 college savings plans more commonly waive maintenance fees altogether. Notable states that also waive their maintenance fees altogether are Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Tennessee.

In addition, where there are no Federal tax deductions for contributing to an ABLE account (nor a traditional 529 college savings plan), many states do provide a state tax deduction for 529A plan contributions. Currently, this includes the states of Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia offering a state tax deduction, which applies for new deposits (either in cash, or as a rollover from an existing 529 college savings plan for a disabled beneficiary).

Ironically, though, the fact that 529 plans can now be rolled over to 529A plans (since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017) means that residents in the states of Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, West Virginia, and Wisconsin could simply make contributions to traditional 529 plans (for the tax deduction) and then subsequently transfer those accounts to a 529A plan after the tax deduction has been claimed. While this may incur transfer fees (typically $95 when moving 529A assets from one plan to another), and it’s important to check whether the applicable state has a recapture tax on the deduction if not used directly for qualified higher education expenses, the state-tax deduction may yield a positive result in at least some states.

Fortunately, organizations like the ABLE National Resource Center have developed 529A plan comparison tools to evaluate at least some of the key features (and tax rules and state-specific limitations) from one state to the next.

Working With 529A Plans As A Financial Advisor

While it is our job to be on the forefront of financial products and solutions for clients, 529A accounts are particularly challenging, as most have not yet been tailored for mainstream use by financial planners. And recent regulatory hurdles are making them even more difficult to facilitate.

In practice, virtually all 529A plans are “direct-sold” plans – in other words, they’re made available directly to consumers, and not available through an advisor. The only current alternative is Virginia, which offers the ABLEAmerica plan from American Funds, though it is an A-share broker-sold option. Thus, there are not currently any 529A plans that are available in a fee-based structure or are otherwise feasible for an RIA to charge an ongoing advisory fee from the ABLE account itself (though in theory the advisor could simply bill an overall Assets Under Administration [AUA] fee to the client directly, and include the value of the 529A plan in the calculation).

On the other hand, the reality is that only two reallocations are allowed per year in an ABLE account, so justifying an ongoing management fee may be difficult anyway, beyond the initial advice process to establish the account (and weighing it against alternatives like a special needs trust). In addition, 529A plans tend to be much more “transactional” in nature, as paying for a person’s care may incur daily, weekly, and monthly expenditures on an ongoing basis… while realistically a 529 college savings might accumulate untouched for years or more than a decade, and then only be used once or twice a year when tuition payments are due (depending on the particular school’s tuition payment plan options). Which even raises the question about whether brokers should be allowed to receive trails for C-Share funds in ABLE accounts anyway when there is limited ongoing investment management and a potentially large volume of ongoing distributions depleting the account.

Yet in many cases, the advisor simply wants to be able to support the client’s ongoing use of the account as an advisor… and unfortunately, at this point, there are no “advisor-supported” 529A plans.

One potential workaround is to have a client authorize you as a financial representative on an account, using an RIA agreement, and operating through a traditional RIA custodian (at least where the RIA custodian is otherwise willing to facilitate the process). For instance, Fidelity allows the client open an ABLE account on their own, through either Fidelity’s own 529A plan, or the ABLEAmerica plan, and then have them sign off on an RIA Authorization Agreement adding the advisor to the account, and then “house” the client’s ABLE account through the Fidelity platform. This helps to make our relationship with the client more “sticky,” even though we cannot charge a fee or make revenue on the account. In addition, we can trade and transact on the client’s behalf in their 529A plan through Fidelity, and become a valued partner in the management of the ABLE account. The ABLE account can then also integrate with performance reporting software, creating better transparency, and overall coordination and organization of the client’s household assets. The obvious detriment here is Fidelity has been the only platform to allow an RIA agreement on the account, and it is restricted to otherwise using the Fidelity or American Funds 529A plans.

Legislative Outlook And Future Developments For 529A Plans

While 529A plans are somewhat of a “frontier” investment, it seems that there is national momentum to create advantages and incentive for families to take responsibility in saving for a special needs family member.

For instance, beyond the creation of 529A plans themselves (as a [permanent] part of the Tax Extenders legislation in 2014), and the more recent ability to roll over from 529 plans to 529A plans, new as of 2018, 529A contributions are eligible for the Saver’s Credit as well. The Saver’s Credit, traditionally for those who contribute to their own retirement accounts, provides a tax credit up to $1,000 per year, and will now be available for disabled individual beneficiaries who do earn income and are able to save it into their own 529A plan.

There is also active discussion on increasing several of the current age limits and restrictions within ABLE accounts.

For example, under current rules, disability must be declared before age 26 to qualify for making contributions to a 529A plan. If a disability arises in early adulthood, this cutoff may prove burdensome, so rightfully, there have been talks to increase the age threshold. One recent legislative proposal introduced in the Senate would increase the ABLE account age limit to 46.

Secondly, the annual $15,000 contribution limit (tied to the Federal annual gift limit) has also been the subject of discussion. For some, allowing a higher contribution limit may allow more flexibility in early planning and asset sheltering if trying to qualify for state and federal assistance. The ABLE to Work Act of 2017 would potentially allow an ABLE account beneficiary to make additional contributions equal to the lesser of the beneficiary’s compensation, or an amount equal to the federal poverty level for a one-person household.

While these changes are still in the works, and may or may not ultimately come to pass, it is a welcome sight to see 529A accounts receiving diligence and attention from regulators.

The bottom line, though, is simply that while there is certainly room for improvement in letting advisors manage 529A plans more directly, the most value an advisor can bring is helping facilitate the conversation about planning for a special needs beneficiary, and implementing a team approach. It would be wise to consult with an attorney who can help weigh the pros and cons between a traditional special needs trust and a 529A plan, and determine the appropriate blend that is in the client’s best interest. Arguably, this reason is at the forefront for why your clients are working with you… and will continue to do so, despite the current limitations.