Executive Summary

The current regulatory oversight structure for advisors is a patchwork combination of FINRA, SEC and state securities regulators, and state insurance regulators, depending on which types of insurance or investment products/services the advisor offers. Regardless of the regulator, though, the compliance process is substantively similar for all of them: the advisor is evaluated based on the final solution that is sold/implemented, and the focus of compliance is on substantiating that particular product recommendation or investment portfolio implementation.

Under the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, though, a new standard is emerging, in a manner that transcends the traditional dividing lines of product channels: that the advice must be in the best interests of the client. Which means not only must the product have been reasonable and not UNsuitable… a prudent expert would have to concur that the recommendation itself was actually in the best interests of the client and improved his/her situation.

In today’s compliance landscape, though, this introduces significant new challenges. The financial services industry has not adopted a standardized advice process for advisors to consistently adhere to, in order to demonstrate their fiduciary duty of care and due diligence. Nor is there any clear agreed-upon framework to determine when a particular recommendation is “best” or not, based on a specific set of client goals and circumstances.

Fortunately, technology can help to solve these problems, but will require a significant change from the compliance technology tools today. This may entail a shift in financial planning software (from being a mere analytical tool for advisors to an actual oversight tool for financial institutions), or the development of third-party software that takes an established advice process (or creates a new one) and institutionalizes it with due diligence and procedural checklists.

Or alternatively, the DoL fiduciary rule may actually spawn the next generation of “robo-advice” software, designed not directly for consumers, but as a compliance-driven solution to ensure that all advisors in the organization are giving the same consistent advice… and potentially transforming the financial advisor from the one who crafts the client advice, to someone who instead simply delivers the institution’s computer-generated advice and helps the client take the necessary steps to change their behavior, follow through, and implement?

Oversight Of “Advisors” Has Historically Focused On Products, Not Advice

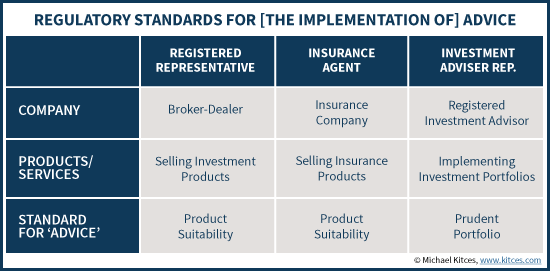

While the use of the term “financial advisor” and “financial consultant” has exploded in popularity over the past 20 years, legally most “advisors” are not actually regulated as advice-providers.

Instead, the largest number are registered representatives of broker-dealers – technically, salespeople who are compensated to sell the financial services products that their company makes available. To the extent they give any advice at all, it is represented as being “solely incidental” to the sale of products (otherwise, those brokers would actually have to register as investment advisers).

Accordingly, the legal standard to which most advisors are held is a “suitability” standard – requiring that the products they recommend be “not UNsuitable” for the client. Technically, it doesn’t actually matter what advice was provided (or not) in the lead-up to the product recommendation. Ultimately, the actions of the “advisor” are judged solely by whether the subsequently-implemented product was suitable.

Similarly, insurance agents are also held accountable based on the suitability of the annuity and insurance products they recommend… not necessarily the advice that was provided in the lead-up to the sale.

In fact, even in the context of a registered investment advisers (RIAs), because ultimately their legal oversight is based primarily on the delivery of (ongoing) investment management services, RIAs are judged not directly on their “advice”, but on how their portfolio recommendations for the client are implemented. Under current law, it’s not a ‘problem’ for a retirement advisor to tell a client to spend too much (or too little) in retirement, or to transfer money from a 401(k) plan to an IRA the advisor will manage, as long as the portfolio itself is prudently designed based on the long-term retirement goal time horizon, required return, and risk tolerance.

In other words, notwithstanding the broad range of labels regarding financial advisors and the delivery of financial advice, the regulation and oversight of those advisors and that advice is predicated almost entirely on the investment or insurance products implemented after the advice. We don’t actually regulate the quality of the advice itself.

Accordingly, the sad reality is that financial services firms can spent little or no time overseeing what advice the advisor gives, nor established any systems to monitor the advisor’s advice process. Compliance oversight is focused entirely on what product is actually implemented for the client after the advice, rather than the advice itself.

How DoL Fiduciary Requires Compliance Oversight Of Advice Itself

In this context – where virtually all financial services firms don’t actually oversee an advisor’s advice or process, just the product-implemented outcomes – the Department of Labor’s (DoL) fiduciary rule introduces a unique new wrinkle: the shift from a suitability standard to a fiduciary standard pertaining to investment advice for retirement investments.

The significance of this shift is that under a suitability standard – where the recommendation has to be not UNsuitable – the ultimate test is effectively whether the product was reasonable for the client to purchase. Notably, that doesn’t mean the product has to be better and improve the client’s situation. Obviously, the client likely expects that the product will improve their outcomes and ability to achieve their goals, or it wouldn’t be purchased. But the advisor is not actually accountable for whether the product improves the client’s situation – only that it’s not blatantly detrimental (i.e., not UNsuitable).

By contrast, with a fiduciary standard, the advice must actually be in the client’s best interests, which means a prudent expert would have made a similar recommendation given a similar client situation (and without any financial self-interest). Or viewed another way, the client can’t simply have believed that the recommended product will improve their ability to achieve their goals. An objective evaluation of the recommendation must conclude that it improved the client’s situation, such that the advice met the Best Interests obligation to the client when the advisor is compensated for that advice.

In addition, because the DoL fiduciary rules span a wide range of products – including not just traditional investment options like stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and ETFs, but also variable and indexed annuities – the fiduciary rule will for the first time directly raise the question of when one type of product is objectively better as a solution for a client than another investment alternative (e.g., when/how an annuity is better than a portfolio, or vice versa).

What IS The Objective Standard For Quality Financial Advice?

The challenge of implementing a prudent expert standard for the delivery of retirement advice is that, in the current landscape, there is not necessarily clear consensus on what “prudent” experts would recommend to better various client circumstances.

For instance, when it comes to the prudent expert standard for portfolio design, there is a recognized and accepted framework – Modern Portfolio Theory – used to evaluate whether a portfolio was objectively well-constructed. In turn, best practices in executing that portfolio design process have evolved over years and decades, now codified into frameworks like Fi360’s Prudent Investment Process.

In the context of financial advice for retirement, though, there is no universally accepted framework for determining what is objectively “better” (or worse) retirement advice. In fact, neither advisors nor academics even yet have a clear consensus on how to measure what constitutes a “better” retirement outcome in the first place. Nor in the context of DoL retirement advice in particular, is there a recognized and standardized “retirement planning process” that an advisor can rely upon, and use as a legal defense to substantiate that “all” the relevant facts and circumstances were considered when crafting the “best” retirement recommendation (or at least, one that a prudent expert would agree was leading to an improved outcome for the client).

In theory, the CFP Board’s 6-step process and supporting Practice Standards might form the framework for an advice standard, though arguably their process is still too broad to form a clear evaluation of whether a particular recommendation was in the best interests of the client. In addition, the scope of the financial planning process is ultimately broader than the retirement advice context of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule (which is solely for Retirement Investors). A better alternative may be the Practice Standards associated with the Retirement Income Industry Association (RIIA) and their Retirement Management Analyst (RMA) certification, which includes its own Practice (Standards) Manual and a supporting Procedural Prudence Map for retirement advice. Yet as it stands now, RIIA's standards are expected only of those who earn the RMA certification as their retirement income designation of choice; it has not been institutionalized across the industry.

The Compliance Technology Gap In Overseeing Advice

Notably, a key requirement of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, and the related Best Interests Contract Exemption, is that not only must advisors meet the Impartial Conduct Standards of providing investment advice in the best interests of their [retirement investor] clients, but Financial Institutions that allow conflicted advice must adopt Policies and Procedures to designed to prevent violations of those Impartial Conduct Standards. Or viewed another way, financial institutions (including advisory firms themselves) now have an oversight responsibility pertaining to whether the advice their advisors provide really betters the client’s situation.

In today’s landscape, this presents a significant challenge for large financial services firm, whose compliance processes and tools are still built primarily around the suitability of the product being recommended, not the advice being delivered. In fact, many firms don’t even have a process to capture the details of what advice, exactly, the advisor even delivered, before the final stage of product implementation. And as noted earlier, there’s certainly no framework to do the supervisory objective analysis of whether the advisor’s advice actually meets the prudent expert standard.

Given these challenges, I suspect we’ll see several prospect solutions emerge in the coming year, as the April 10th 2017 effective date approaches for the Impartial Conduct Standards, and especially as the January 1st 2018 deadline arrives for Financial Institutions to fully implement their Policies and Procedures obligation.

Advisor FinTech Opportunities For DoL Fiduciary Compliance

The starting point for new advisor fintech solutions to meet the DoL fiduciary compliance burden may simply be technology to help support the requisite due diligence and data gathering process itself, in order to substantiate that the advisor’s fiduciary duty of care was met. This could include everything from “robo” data gathering tools to help clients enter their financial information (e.g., via financial planning software like MoneyGuidePro's new Best Interest Scout, personal financial management tools like the eMoney Advisor dashboard, or standalone data gathering tools like PreciseFP), to analytics software that brings in external data on the prior 401(k) plan’s investment choices and costs (e.g., from providers like BrightScope or Morningstar’s recently-acquired RightPond).

However, such tools still don’t necessarily provide a central location for the delivered advice itself, and the supporting analytical process, to be monitored. Which raises the possibility that financial planning software itself may actually become a central compliance software solution in the future. As is, compliance departments already have at least some oversight into how financial planning software is used, though most commonly that relates to questions like “what investment assumptions are being used in the planning projections” and not “what analyses were conducted and what recommendations were presented to the client.” Ironically, most financial planning software doesn’t even have the capabilities to create the client’s written financial planning recommendations directly in the software itself – instead, it’s often handled outside the software, with a separate “Action Items” or “Recommendations” document the advisor creates. In the future, it seems likely that even more of the “financial plan creation” process will happen inside the software. This may include not only tying recommended advice and action items directly to the related analyses, but also incorporating product sales illustrations directly into the financial plan – necessary to substantiate that the recommendation was not merely suitable on a standalone basis, but one that a prudent expert would objectively affirm was able to improve the client’s situation and therefore was in the client’s best interests.

Another possibility is the rise of some sort of third-party “advice oversight” fintech solution – ostensibly a series of process checklists to validate the advisor’s duty of care and due diligence in crafting the recommendations to the client, perhaps by codifying the advice processes promulgated by the CFP Board or RIIA. Notably though, even in this context, oversight of the advice process still leaves a gap about determining what the “right” final advice is. For instance, in medicine, there are not only clear processes that stipulate “if patient presents with symptom A, the appropriate diagnostic process is to run tests B and C” but also recognized diagnostic outcomes: “If the patient’s final diagnosis is X, the correct prescription is Y, and Z is contraindicated.” With financial planning and retirement advice, though, we still struggle with the fact that two advisors may engage in the same duty of care and due diligence process, gather the same data and client goals, yet “conclude” with different “best interests” recommendations. Over time, true “best advice” practices will likely emerge, substantiated by both ongoing academic research, and perhaps by looking at the best outcomes that occur from a consistent advice process that can be benchmarked. Still, in the near term, the lack of any clear connection between client goals and financial circumstances, and “accepted best practices recommendations” related to them, will be a significant challenge.

Ironically, though, the development of software to aid in conducting the data gathering process, and the analysis of the data, and fitting actually-better recommendations to the results, actually begins to look a lot like a true “robo-financial-planning” platform, where the technology does the heavy “advice” work (crafting recommendations objectively and ensuring advice consistency) and the advisor’s job is simply to deliver the software’s recommended advice. The virtue of such an approach from the perspective of the Financial Institution is that it reduces the company’s liability exposure, given the risk that many companies’ “advisors” aren’t actually capable of giving Best Interests advice because they simply don’t have the training and competency to know what the “best” advice would be. After all, a “centralized [robo] advice platform” can be effectively vetted once up front to ensure appropriate and consistent advice for all, where the client facts come in and the software spits out an advice recommendation; overseeing dozens (or hundreds or thousands) of financial advisors is far more difficult, given that many advisors are giving people advice about their life savings with no more training than a 3-hour regulatory exam about the state and Federal securities laws!

Ultimately, though, the fundamental point is simply that the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule has put a significant and newfound pressure on Financial Institutions to actually and truly oversee the advice that their advisors give, and given the number of advisors and clients involved, some forms of technology solution seem inevitable. Now, it’s simply a question of whether the technology that fills the void is an expansion in the role of financial planning software, the development of new “advice process” software solutions, or the possibility that the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule may end out actually spawning a true “robo-advice” movement as Financial Institutions craft the recommended advice for consumers and the role of advisors shifts to simply delivering that advice and helping clients to (behaviorally) follow through and implement the recommendations!

So what do you think? How will the world of compliance shift in light of the Department of Labor's fiduciary rule? Do you see technology gaps and opportunities? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

I earned my AIF designation with Fi360 a couple years ago. I let the designation expire. They used mutual fund peer groups as a benchmark. I asked the instructor why they did not use the relative index. He did not know . It seems to me their system is geared to help the sales side of the industry.

Michael,

You might be reading to much into the word “best” here to suggest that it extends as far as you describe — all the way to the overall advisory relationship in some measurable qualitative or quantitative manner — such that the advice objectively “improves” the client’s situation. This rule (and the related impartial conduct standards) is MOSTLY about conflicts of interest. So that when it speaks to the client’s best interest it means as opposed to in the advisor’s interest. You made this point in your April 11 piece in which you clearly distinguish between “prudent” advice and “not actually the difficult-to -define best” advice. The FI360 materials have always made clear the prudence, when it comes to investment advice, is about process and not about results.

Now of course in order to document a prudent process you’ve gotta have one. Meaning a financial plan, an investment policy statement, a comprehensible philosophy for choosing products and a monitoring program.

Please, please just stop!!!

No financial planner/IAR or RIA had their liability go up 1 cent as a result of the DOL rule.

-Were you already obligated to do what was in the best interests of a client as an IAR or RIA? Yes!

-Was arbitration done away? No!

-What changed? Nothing… Oh, I have to put like 2 more pieces of info on my website, gee…

The only thing that worried me after this rule came out was intense overreactions to essentially meaningless legislation.

Every advisor with a compliance officer other than themselves is both shaking your head and laughing at this blog post. None of them have a clue about financial planning let alone tax issues, estate planning, etc. If even 10% of what you’re suggesting ever happened it would lead to vicious fights with compliance officers all over the country in ways that got compliance officers to realize how clueless they are about this.

So please, please as respectfully as I can say this, shut up about the DOL rule, and the absolutely zero impact it brings other than overreactions by people who are in capable of comparing the DOL framework to the IAR/RIA SEC framework.

yes advice is about process which at a minimum must include an IPS and an appropriate low cost portfolio implementation…the courts will ultimately determine compliance with fiduciary/best interest standards…but I don’t think it will be that difficult to do

The requirement, as discussed by Fiduciary recent blog post,obligation to “avoid misleading statements, manage assets prudently and with undivided loyalty to the plans and their participants and beneficiaries, and receive no more than reasonable compensation further help to writing a dissertation with easier to know the plannings.

I’m new to blogging and love the technical aspects of it. Thanks for your research and writing. Here’s my very first post, written today:Custom Dissertation UK on a high talk intelligent way to proceeds.