Executive Summary

In theory, the whole point of saving and investing for retirement is that upon reaching retirement, it’s time to spend down the money and enjoy it. In practice, a growing base of research finds that for most of their retirement, retirees are just continuing the growth of their pre-retirement portfolios, suggesting a “consumption gap” between what retirees could and should spend versus what they actually do.

However, the reality is that for a long-term retirement, where compounding inflation can double or even quadruple spending needs after 30 years, retirees actually should allow their portfolios to grow at least slightly for at least the first half of retirement. It’s a necessity just to cover later-years’ spending needs at their inflation-adjusted levels.

Furthermore, given uncertainty about the length of retirement, how high inflation will be, and whether portfolio returns will be favorable or not, often retirees spend even less in the early years just to defend against these risks – an approach now dubbed the “safe withdrawal rate”. Yet given that most of the time markets and inflation don’t actually spiral out of control, following a safe withdrawal rate approach just further increases the likelihood that retirement portfolios will continue to grow throughout retirement.

The end result is that while in theory a retirement portfolio is meant to be spent, in practice most retirees faced with an ever-open-ended potential of living many more years will feel compelled to keep extra assets available, just in case… and never actually reach the point of depleting the retirement portfolio at all! Which, notably, isn’t a sign of inefficient portfolio spending or a consumption gap, but merely the prudent reality of dealing with an uncertain future!

Retirees Aren’t Spending The Way They “Should”

The classic view of retirement is that in the early years people save and invest (the accumulation stage) in order to retire and consume all of their savings (the decumulation stage). As the saying goes, “you can’t take it with you”, so you may as well spend it while you can. Arguably, the whole point of retirement is to enjoy the fruits of your labor.

Of course, the caveat is that spending down retirement assets smoothly is no simple feat. From coordinating amongst various sources of retirement income, to the tax consequences of portfolio withdrawals and IRA and Roth distributions, to the timing of when to begin Social Security (especially for couples), helping people to successfully liquidate their retirement assets is a big business for advisors. Even if that business is to be provided to a declining asset base.

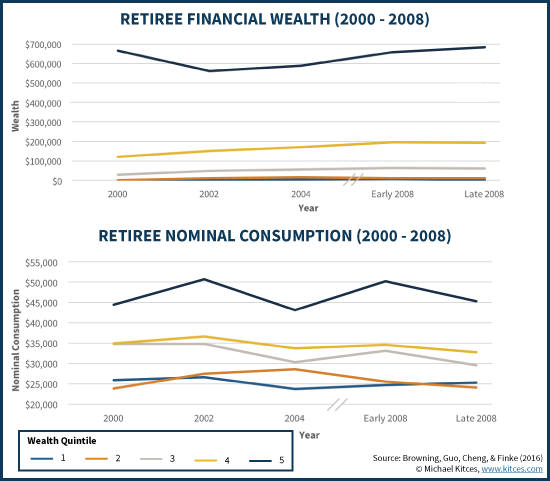

However, the biggest caveat of this conventional view of retirement is that it simply doesn’t appear to be happening. In a recent study entitled “Spending In Retirement: Determining The Consumption Gap” by Browning, Guo, Cheng, and Finke in the Journal of Financial Planning, researchers showed that affluent retirees relying on their portfolios in retirement are failing to even spend their annual income in their retirement years (and the more affluent they are, the worse the trend tends to be). In fact, not only are retirees not fully spending their available income, but their spending actually begins to decline in retirement. As a result, from the beginning of 2000 to the end of 2008 – a very challenging time of mediocre returns for retirement portfolios, when in theory account balances would have dipped with ongoing withdrawals – the average financial assets of wealthy retirees still continued to increase in retirement. Thus, the researchers identified a “consumption gap” between what spending the retirement portfolios could support, and the lesser amount that was actually getting spent (which in turn left room for the portfolios to continue to grow).

Yet given these results, suggesting that retirees are “doing it wrong” by not even spending the full amount of their retirement and portfolio income in retirement and allowing their portfolios to grow, the question arises: are retirees really under-spending in retirement, or is this actually a rational retirement spending strategy for a long retirement time horizon?

When Should Retirees Spend Down Their Retirement Assets?

While the conventional view is that once you hit retirement, it’s time to start spending down retirement assets, in practice the process isn’t so straightforward. While leaving over all your principal at the end of retirement may mean you “under-consumed” your retirement assets, spending down too quickly and running out early clearly isn’t a good result either.

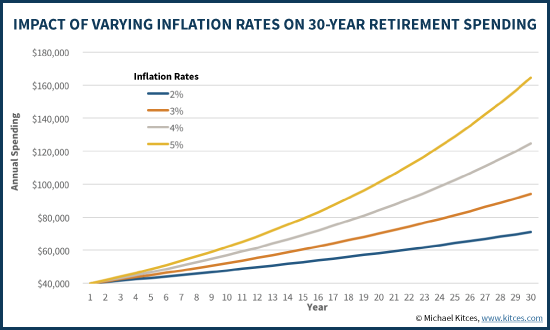

Timing the liquidation of retirement assets is especially complicated by the role that inflation plays in a long-term retirement plan. After all, over a multi-decade time horizon, even modest inflation can add up significantly. As the chart below shows, what starts out as $40,000/year spending can wind up anywhere between $70,000/year and $164,000/year after 30 years, just to maintain the same standard of living, depending on whether inflation averages just 2%/year or is as high as 5%/year.

Given the impact of inflation, it’s problematic to start digging into retirement principal immediately at the start of retirement, given that inflation-adjusted spending needs could quadruple by the end of retirement (at a 5% inflation rate). Accordingly, the reality is that to sustain a multi-decade retirement with rising spending needs due to inflation, it’s necessary to spend less than the growth/income in the early years, just to build enough of a cushion to handle the necessary higher withdrawals later!

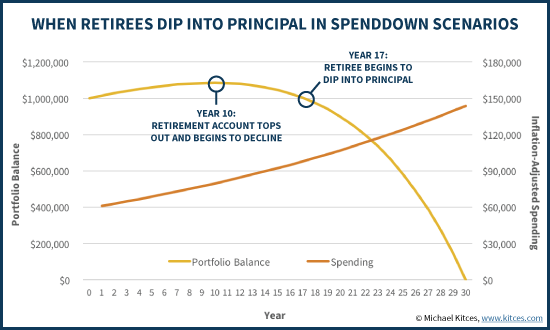

For instance, imagine a retiree who has a $1,000,000 balanced portfolio, and wants to plan for a 30-year retirement, where inflation averages 3% and the balanced portfolio averages 8% in the long run. To make the money last for the entire time horizon, the retiree would start out by spending $61,000 initially, and then adjust each subsequent year for inflation, spending down the retirement account balance by the end of the 30th year.

As the chart reveals, though, projected spending that plans to spend down assets by the end of a 30-year retirement still would spend less than the growth for the first 10 years, and wouldn’t actually dip into principal until the 17th year (out of 30)!

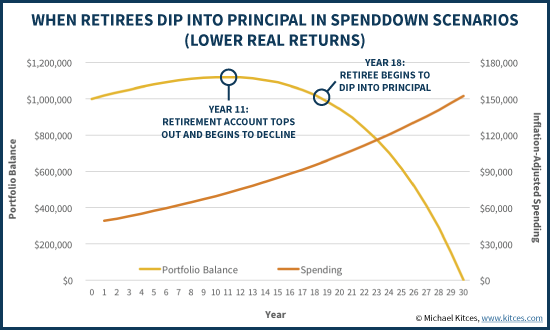

And that’s assuming “modest” 3% inflation and long-term returns of 8% (the approximate averages for the past 100 years). If instead, the retiree had a gloomier outlook, and projected a balanced portfolio to grow at only 7% while inflation could be as high as 4%, spending would be only $49,000 initially, the portfolio would peak in year 11, and dipping into principal wouldn’t occur until the 18th year!

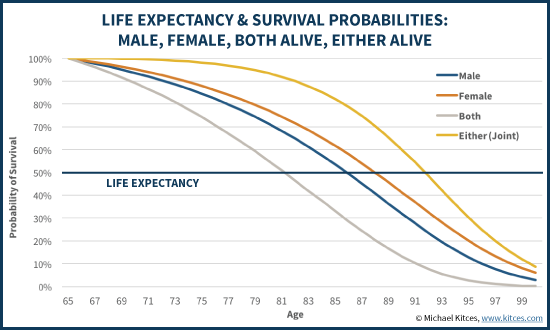

Notably, in the context of this more conservative scenario, a 65-year-old retiree’s life expectancy is only to their mid 80s (or early 90s as the joint life expectancy for a married couple). Which means a significant number of retirees who use this as their planned retirement spending strategy will pass away before they ever materially dip into retirement principal at all!

Similarly, the fact that most “spend-down” strategies won’t actually begin to spend principal until the final decade of retirement also means that for a portfolio-based retirement strategy, required minimum distributions won’t likely deplete the retirement portfolio either, and to the extent they’re not needed may even just be “forced transfers” of investments that were growing in the IRA and will now grow in a taxable investment account instead (but still not be spent, yet).

Managing Sequence Of Return Risk And Spending From Principal

In addition to the reality that even a retiree who intends to spend down principal won’t likely do it until the second half of retirement at best, the additional challenge is that returns (and inflation) are not as ‘certain’ as even straight-line conservative projections suggest. Instead, as we know from the research on Sequence of Returns Risk, even if the returns average out in the long run, if they come in an unfavorable sequence, the retirement portfolio can still fall short.

The solution to this challenge is to spend less – at least initially – “just in case” an unfavorable sequence occurs, which is the origin of the “4% rule”: it is an initial withdrawal rate low enough to have been “safe” and sustainable in any historical bear market scenario.

Of course, the caveat is that on average, the 4% rule is unnecessary. As noted earlier, given long-term average returns, the “safe” withdrawal rate would be over 6%. The 4% rule is built for environments that have horrible returns in the first part of retirement.

Which means if the retiree starts with a 4% initial withdrawal rate and actually does get anything close to merely average returns (and not an especially bad early sequence), the portfolio will just compound even more growth in the early years and get even further ahead.

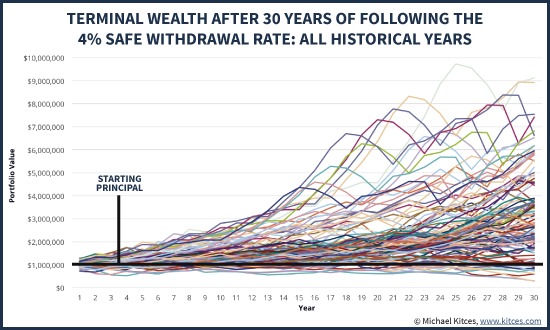

Accordingly, the chart below shows the path of wealth that would have occurred in any particular 30-year historical scenario going back to the 1870s, assuming a 4% initial withdrawal rate (with the dollar amount of spending adjusted each subsequent year for actual inflation) invested in a 60/40 portfolio (annually rebalancing, with the actual stock and bond market returns that occurred year by year).

As the chart reveals, the decision to follow a 4% initial withdrawal rate makes it exceptionally rare that the retiree finishes with less than what they started with, at the end of the 30-year time horizon; only a small number of wealth paths finish below the starting principal threshold. In fact, overall, the retiree finishes with more-than-double their starting wealth in a whopping 2/3rds of the scenarios, and is more likely to finish with quintuple their starting wealth than to finish with less than their starting principal!

Can Retirees Ever Really Spend Down Their Principal?

The bottom line is that from the perspective of whether retirees will likely spend down their assets in retirement, a normal retirement spending pattern suggests that it wouldn’t typically happen until retirees were well into their 80s at best, and following the 4% rule to defend against the risk of running out of money just further amplifies the likelihood of never spending down the portfolio at all. Even a rule that ratchets up spending in the later years still has a high likelihood of leaving significant dollars over at the end as well. The more conservatism in the early years in the face of retirement uncertainty, the more likely it is to have ever-larger retirement account balances later (since “most” of the time, the bad risks don’t actually manifest). Which is even harder to spend down in those later years given a growing base of research suggesting that the growth in retiree spending lags inflation as the years go on.

In point of fact, figuring out how best to balance the need for prudent spending in the early years with the potential for accumulating “excess” retirement dollars in the later years is arguably the greatest opportunity today in retirement income planning. Unfortunately, lifetime immediate annuities don’t necessarily do any better at accomplishing the goal right now, given today’s environment where a lifetime inflation-adjusted immediate annuity for a married couple only pays out about 3.5% at today’s rates as well (no better than following a 4% initial withdrawal rate, and forfeiting the upside potential as well). Although perhaps improving payout rates for longevity annuities, paired with a retirement portfolio, may eventually help to close the gap.

But at a minimum, it’s crucial to recognize that accumulating “excess” retirement dollars and seeing the retirement account balance grow, particularly in the first half of retirement, doesn’t mean the retiree is underspending. In fact, spending down the retirement principal early in retirement would be a sign of trouble. Accumulating continued growth throughout the early years of retirement is actually the normal, prudent course of action for anyone who anticipates living a long time, fears the potential impact of future inflation, and therefore recognizes the need for the retirement portfolio to grow in the early years to defend against the uncertainties of a long retirement future.

So what do you think? Do you see your retired clients actually spending down their retirement portfolios? If so, when do they actually begin to draw down? If not, is it because they're still protecting against an unknown future, or some other reason?