Executive Summary

Planning for incapacity is one of the most important aspects of a sound financial plan, and one that is taking on increased importance as the Baby Boomer generation continues to age in record numbers. But while medicine has not yet reached the point where it can prevent (or reverse) all cognitive and physical impairments, there are a number of tools that can be used to ensure one’s finances continue to be managed effectively in the event that diminished capacity becomes a reality.

One common approach used by individuals looking to allow a trusted family member to manage an account on their behalf is to simply add that person to the account as a joint owner. These so-called “convenience accounts” are generally easy to establish, but can lead to a number of unforeseen problems.

For instance, once an individual is added as an owner to an account, they have access to the funds within the account and may be able to use those funds for their own benefit, as opposed to their intended purpose. Similarly, adding an additional owner to an account can subject the account’s assets to the new owner’s creditors. Even in the best of scenarios, this “strategy” can prove problematic, as certain assets, such as IRAs and other retirement accounts, cannot be turned into joint convenience accounts in the first place.

A second way of allowing someone to assist in the management of an account is through the use of a Power Of Attorney. Powers of Attorney are tried and true legal documents that can be drafted in a number of ways to meet an individual’s desired outcome. A General Power Of Attorney, for instance, can be used by a Principal to grant an Attorney-In-Fact a broad array of powers over virtually all assets. A Limited Power Of Attorney, on the other hand, can be used to give an Attorney-In-Fact only specifically enumerated powers, and/or powers over only specifically enumerated assets.

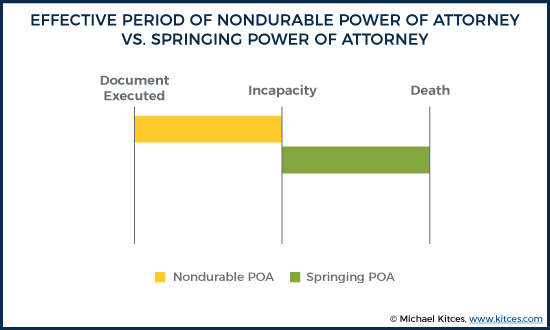

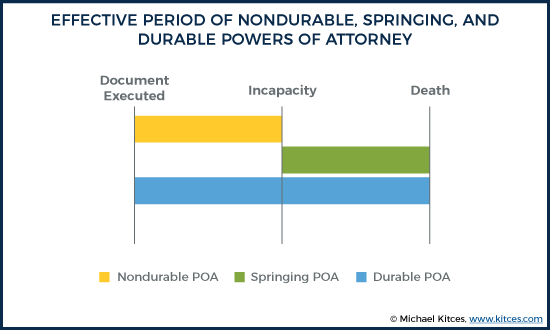

When using a Power Of Attorney to provide for account administration in the event of incapacity, it is critically important to make sure that the Power Of Attorney actually remains in force at that time! Thus, instead of a Nondurable Power Of Attorney, which is no longer effective once the Principal is incapacitated, planning should incorporate either a Springing Power Of Attorney, which typically only becomes effective at the time of incapacity, or a Durable Power Of Attorney, which is effective upon execution of the Power Of Attorney document and remains in effect even after incapacity.

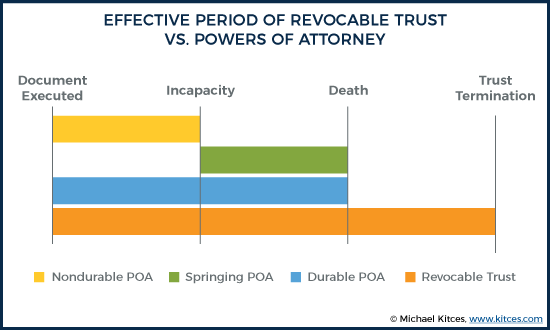

Finally, some individuals may wish to use a Revocable Living Trust to allow for continued management of accounts and financial matters in the event of their incapacity. Revocable Living Trusts are often more expensive to create, but because the Revocable Living Trust actually takes title to accounts and assets, they also offer benefits not available when a Power Of Attorney is used.

Revocable Living Trusts, for example, are less likely to be rejected or held up in lengthy legal department reviews by financial institutions. Also, unlike the rights conveyed to an Attorney-In-Fact via a Power Of Attorney, which end no later than the Principal’s death, the rights granted to a Trustee via a Revocable Living Trust can continue after the Trust creator’s death, allowing for effective post-death management of assets as well.

Notably, though, whichever approach(es) is(are) used, it is critical to act before an individual becomes incapacitated and can no longer legally act on behalf of themselves. Powers Of Attorney should be submitted to financial institutions before they are actually needed, and Revocable Living Trusts should be properly established and funded in advance. Absent such actions, one’s financial affairs may be left up to the mercy of the courts... when time is of the utmost importance.

One of the most important aspects of a “complete” financial plan is planning for the potential for diminished capacity, or even worse… incapacity. Such limited capacity scenarios can be caused by physical injury or, more often in the case of retirees, diminished mental capacity due to cognitive decline or diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Situations in which someone is incapacitated are only likely to increase as the Baby Boomer population continues to age. Today there are roughly 5.8 million people in the United States living with Alzheimer’s-related dementia, of which a whopping 97% are age 65 and older. And absent some sort of medical breakthrough with respect to treating dementia, that number is set to more than double over the next three decades as longevity increases and more and more people make it to the advanced ages where such conditions are more likely to occur.

Unfortunately, though, when an individual becomes incapacitated or is suffering from cognitive impairment, life doesn’t stop… and neither do bills... or the need to manage one’s investments and other financial affairs. And without proper planning in advance, the situation can quickly deteriorate from bad to worse.

Absent planning in advance, an incapacitated person will generally need to have a guardian appointed for them by a state court. But who should that be? Family infighting can quickly ensue.

Even in the best of scenarios where families are aligned, relying on courts to approve a guardian can prove to be a time intensive and expensive process. And in the interim, no one may be able to make needed changes to the incapacitated person’s accounts, nor access their funds to pay bills, including both doctor’s bills and the basic bills required to maintain a residence (such as property taxes and utilities).

To avoid such problems, individuals are generally best served by taking matters into their own hands and selecting someone to act on their behalf when they are no longer to do so. This is accomplished by making choices, taking action and, more often than not, executing certain documents while they still have the mental and physical capacity to do so. What follows then, is an overview of some of the most common options (as well as tactics to avoid) for giving a trusted family member access to financial accounts so that in the event of incapacity, they can “step in” and ensure that your financial affairs continue to be handled timely and efficiently.

Author’s note: This article deals primarily with property law and laws that apply in various fiduciary arrangements, such as powers of attorney and trusts. Such issues are generally a matter of state law. As such, while the information below is meant to highlight the rules that typically apply, and the problems and planning opportunities that may arise from such, differences may apply in certain jurisdictions.

Option #1: (Why You Shouldn’t) Create A “Convenience Account” By Adding A Trusted Family Member As Joint Owner Of An Account/Asset

In many instances, the easiest way to grant another person authority over an account is to simply make them a co-owner of the assets by establishing a joint account (or adding them as an additional owner to an existing joint account). For instance, a joint account owned by “mom” can be retitled to a joint account owned by mom and daughter. Similarly, a joint account owned by “mom and dad” can be converted into a joint account owned by mom, dad, and daughter.

Such accounts, where an additional owner is added purely for the sake of giving them the ability to access the funds on behalf of the “real” owner, are commonly known as “convenience accounts.” In some situations, such accounts may be specifically identified as convenience accounts by the financial institution. Many times, however, a convenience account is just a joint account with a specific purpose… giving another person access to the account for administrative purposes.

In choosing this approach, the original account owner(s) is(are) able to avoid the need for professional legal work, facilitate the change at no cost (other than, perhaps, some nominal administrative fees), and complete the change in short order. But as is often the case with quick and easy “fixes,” this “solution” is far from ideal and, in fact, can lend itself to a number of significant problems.

Retitling Accounts Means It’s Not “Just” The Original Owner’s Assets Anymore

Establishing a joint account creates joint ownership of assets. Which means an owner added to an existing account will have full access to the funds in the account, because it’s now their money too. And while doing so can enable a healthy child to have access to funds to pay for mom’s medical bills, it also gives the same healthy child the same access to the same funds to… say… pay off their own mortgage, buy a new sports car, transfer the funds to another account, or… well, you get the point.

Simply put, joint accounts virtually eliminate any checks and balances there might otherwise be over a family member’s funds. Even if a custodian, banker, advisor, etc., suspect that something is “not quite right” about a requested transaction, their hands are generally tied, and they must process the transaction accordingly if those instructions are received from an owner(!) of the account.

The “good(ish)” news is that when – or more appropriately, if – this sort of malfeasance is discovered, there may be a way to recover misappropriated funds. The problem, however, is that doing so will generally require expensive and time-intensive legal action. And even then, nothing is certain. In order to recover any funds, the other joint account owner (or a party acting on their behalf) must generally prove that the joint account relationship was merely established for “convenience,” and that the added joint owner was really “just” an agent of the other owner, and therefore, owned them a fiduciary duty to act in their best interest.

Adding A Joint Owner Can Subject Assets To Additional Creditors

One of the most troubling aspects of using a joint account as a means of allowing someone else (e.g., a family member) to oversee and handle assets is that it potentially exposes the account itself to the overseer’s creditors and other financial problems as well. As the general rule for creditor protection is that “if you can get to your own money, so can your creditors.” And we’ve just established that if you have a joint account, you have access to the money within the account… so, naturally, so would your creditors.

Imagine, for instance, that mom decides to add her son “Johnny” as a joint owner of her $1 million brokerage account so that he can help manage the account’s investments for her. One day, several years later, Johnny is on his way home from work when he hears on the radio that one of the companies in which he invested mom’s money was acquired, and its stock price has jumped. Excited about the prospects of his “victory” for mom, Johnny pulls out his phone to look up the current price of the stock… while he is still driving.

You know what happens next.

The ensuing accident is completely Johnny’s fault. In the resulting lawsuit, Johnny is sued “for everything he’s worth.” Unfortunately, that would generally include his (very) recently established joint account. Thus, through no fault of her own, mom could be out $1 million.

(Note: If mom can prove that the joint account was established purely for her convenience [i.e., it was a convenience account], she may be able to protect her funds from Johnny’s creditors. But the burden to prove the money was really hers, that Johnny was only added for her convenience, and that she didn’t actually intend the joint account to be a way of transferring assets to Johnny will be on mom. Thus, at best, she’s probably looking at substantial legal fees to defend her savings.)

And creditors from a tort lawsuit or a defaulted loan are far from the only people who may lay claim to the assets. (Soon-to-be-)ex-spouses may have a right to some of the assets too!

Suppose, for example, that Johnny wasn’t alone in the car above, but rather, his infant child was in the back seat. Appalled by her husband’s lack of common sense, Johnny’s wife immediately files for divorce. The assets in the newly established joint account could be “up for grabs” as part of the proceedings!

(Note: Once again, if mom can prove that the joint account was established purely for her convenience, she may be able to preserve her funds by keeping them out of the divorce proceedings. However, in general, the presumption will be that the account was established with the goal of creating joint tenancy. Further, while such property may be considered separate property, in certain cases, a judge may order the division of separate property as part of an “equitable distribution.”

Not All Assets Are Eligible To Add A Joint Owner For Assistance

Even if an account owner was willing to disregard all of the risks and potential issues associated with using a joint account to allow an individual to help manage their affairs, the approach is also limited simply because retitling certain types of assets as joint property can be difficult, if not impossible.

IRAs, Roth IRAs, and other retirement accounts, for instance, cannot be converted to joint accounts. There is no such thing as a “joint IRA.” The “I” in “IRA” stands for “individual,” and only an individual – a single person – can be the owner of an IRA during their lifetime.

The only way to get an IRA “into” a joint account would be to distribute the funds from the IRA in a taxable distribution and move them into a joint account. Of course, at that point, it’s no longer IRA money. It’s “just” money in a joint account that used to be IRA money! And doing so would be a fully taxable liquidation event for the entire IRA!

Of course, IRAs and retirement accounts are far from the only accounts that can’t be converted to joint accounts. For example, jointly owned annuities exist, but adding a child as a joint owner of a contract after it has been established can similarly trigger immediate income tax consequences for any gains (under IRC Section 72(e)(4)(C)). It can also be challenging to change ownership of certain privately held investments, such as privately held stock that may have bylaws-mandated restrictions on ownership and transfers. And like IRAs, other tax-favored accounts, such as HSAs, can’t be turned into joint accounts.

Thus, even in the best of situations, the add-a-person-as-a-joint-owner-of-an-account approach is limited.

Option #2: Use a Power Of Attorney (POA) To Name A Trusted Family Member As An Attorney-In-Fact

Another way - and in general, a much better way - to allow another individual to gain access to an account to help manage the account and/or facilitate transactions to/from the account is to name them as an Attorney-In-Fact via a Power of Attorney document.

A Power Of Attorney is a legal document that grants an individual (or group of persons, or even an organization) the right (i.e., the power) to act on another person’s behalf. It creates a fiduciary relationship between the document’s creator, referred to as the “Principal,” and the Attorney-In-Fact, who becomes an “Agent” of the Principal.

Critically, though, while an attorney-in-fact becomes an agent for the owner, the attorney-in fact does not become an owner of an account over which they have been granted power. Furthermore, by virtue of the fiduciary nature of the Attorney-In-Fact’s relationship, the Attorney-In-Fact is legally required to act in the Principal’s interest, exercising (amongst other duties) a duty of loyalty to not use the money for themselves.

However, one practical challenge is that while a valid Power Of Attorney document may legally allow the Attorney-In-Fact to “step into the Principal’s shoes” and act on their behalf, there is no central “Power Of Attorney database” or other method to instantly and/or automatically let all of an individual’s financial institutions know that such a document has been executed (side note for FinTech entrepreneurs: this seems like a perfect candidate for blockchain technology to revolutionize!?). Rather, the Attorney-In-Fact must generally provide a copy (or sometimes an/the original) of the document to each of the institutions at which the Principal holds an account prior to actually being able to exercise their legally-granted authority.

An additional complication to using a Power of Attorney is that institutions don’t always know when such a document is still in force, as the granting of authority over an individual’s financial assets does not last forever, either. Instead, a Power Of Attorney will expire when the Principal does (i.e., the Attorney-In-Fact’s authority to act on behalf of the Principal ends when the Principal dies), and may expire even earlier (as discussed further below) when certain conditions are met. And of course, Principals can alter and revoke their own Power of Attorney documents as well (which makes Financial Institutions all the more cautious to verify that a current Power of Attorney document is really current).

General Powers Of Attorney Vs. Limited Powers Of Attorney

In many instances, when a Power Of Attorney is created, the goal of the Principal is to grant their Attorney-In-Fact the authority to act on their behalf to the extent legally possible, and with regard to all of the Principal’s assets and accounts. Such a Power Of Attorney document is known as a “General Power of Attorney.”

Alternatively, when desired by the Principal, a Power Of Attorney can be drafted such that it provides the Attorney-In-Fact a narrower set of powers and/or authority over a more limited group of investments. Such a Power Of Attorney document is known as a “Limited Power of Attorney.” Such documents can be extremely useful in a variety of situations. Consider the following:

Example #1: Bill’s wife recently passed away. During her lifetime, Bill’s wife effectively managed all of the couple’s finances, including the investment management of their various accounts.

Bill is in good physical and mental health and wants to maintain control over distributions from his account. He has no interest, however, in learning about investments or figuring out what should actually be in his account. Bill’s son, on the other hand, is an avid investor. Bill can, if he wishes, execute a limited Power Of Attorney, giving his son only the power to change investments within his account, but no power to effect distributions from the account, or to make any other changes.

Example #2: Tyrone is an investor who is currently working with an estate planning attorney to craft his “just in case” documents. He has a number of “regular” financial accounts, including an IRA, a Roth IRA, a taxable brokerage account, a checking account, and a savings account, all of which he believes can be effectively managed by his wife.

Tyrone is also very active in the cryptocurrency space, and has accounts established at a number of online cryptocurrency exchanges. And while he trusts his wife implicitly, he believes that if for some reason he were incapacitated or otherwise disposed, his friend, Sean, who is also a cryptocurrency investor, would be better equipped to help manage his cryptocurrency accounts.

In such an instance, Tyrone could create a limited Power Of Attorney, naming Sean as his digital Attorney-In-Fact, or as his Attorney-In-Fact just for his cryptocurrency accounts.

Note: Discretionary Investment Advisors should be intimately familiar with Limited Powers Of Attorney. It is, in fact, a Limited Power Of Attorney which grants the Investment Advisor the ability to make discretionary trades within a client’s account and, in certain circumstances, to deduct advisory fees from the account.

Nondurable Vs. Springing Vs. Durable Powers Of Attorney

Occasionally, an individual may look to allow a family member to access an account to provide management or facilitate transactions, even while they are healthy and otherwise capable of handling those things themselves. Oftentimes, however, the bigger concern is: “If something happens to me, I want to make sure that someone can continue to access my accounts so that investments can continue to be managed, bills can continue to be paid, etc.” In such situations, it is necessary to have either a “Springing Power Of Attorney” or a “Durable Power Of Attorney.”

As noted above, an Attorney-In-Fact’s powers end no later than when the Principal dies. But again, depending upon the nature of the Power Of Attorney agreement, those powers may terminate long before the Principal’s death, too.

In fact, absent language to the contrary, the powers granted to an Attorney-In-Fact by a Principal via a Power Of Attorney will generally terminate (i.e., the Power Of Attorney becomes null and void) at the earlier of the:

- Principal’s Death

- Principal’s revocation the Power Of Attorney

- Expiration date “built in” to the Power Of Attorney

- Principal’s incapacity/mental incompetence

Note the final termination event listed above: incapacity. Now think about it… if your goal is to make sure that in the event you are incapacitated and unable to handle your own financial affairs that someone else can seamlessly step in to take your place, then what good is having a Power Of Attorney document that removes that trusted person’s authority precisely at that moment?!

Thus, while a Nondurable Power Of Attorney can make sense – if, for instance, you’ve granted powers for someone to help manage certain affairs in your stead but under your direction, and you don’t want them to continue to do so when you’re no longer able to direct them (because you’re incapacitated), if the goal is continuity of management through incapacitation – or to take effect when incapacitated – such a document won’t work. And that’s where either a Springing Power Of Attorney or a Durable Power Of Attorney comes into play.

The (Problems With A) Springing Power Of Attorney

You might think of a Spring Power Of Attorney as the “Yin” to a nondurable Power Of Attorney’s “Yang.”

More specifically, whereas a “plain old” nondurable Power Of Attorney grants the Attorney-In-Fact powers immediately upon execution, but ending at a specific event (the Principal’s incapacity), the Springing Power Of Attorney grants no power to the Attorney-In-Fact until a specific event occurs. Then, once that “triggering event” – commonly incapacity – occurs, the Attorney-In-Fact’s powers “spring to life” (thus the “springing” name), and he/she can begin acting on behalf of the Principal.

This type of Power Of Attorney is appealing for obvious reasons. Many individuals prefer to maintain sole control over their assets until they are no longer able to do so. And if the goal is to allow a family member to continue managing an account only after the account owner (the Principal) is no longer able to do so themselves, then why give the Attorney-In-Fact any power before that time?

In theory, it all sounds great. Unfortunately, in practice, though, the Springing Power Of Attorney can be rather problematic.

Example #3: You have been named as the Attorney-In-Fact for your elderly mother, who has executed a Springing Power Of Attorney that is to take effect upon your mother’s incapacity. During your most recent visit with your mom, you notice that she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things that happened only moments ago.

Furthermore, as you head into the living room, you find a large stack of unpaid bills stretching back several months. It is now clear to you that, although it’s something you have tried to avoid, your mother’s cognitive impairment has reached the point where it is time for you to take action as her Attorney-In-Fact.

Continuing on, you begin to sort through the bills until you reach one that looks rather ominous. It has a big red stamp across the front that says “Final Notice. Return Immediately.” You open the envelope to find that it’s the electric bill, and it hasn’t been paid for months. In fact, the notice says that if payment has not been received in just three more days, service will be suspended.

Aghast, you turn to your mother and ask why she hasn’t paid the bills, to which she replies, “I have, and mind your own business.” Rightfully concerned, as the electricity is days away from being shut off, you immediately leave the house and head to the bank, Power Of Attorney in hand, where mom maintains her checking account. As you reach the teller, you let her know that you need a check from your mother’s account immediately so that you can pay her electric bill. Accordingly, you present her with the Power Of Attorney and tell her that, “Sadly, mom is no longer capable of handling her affairs.”

Here’s the problem though… you don’t necessarily get to make that call. Rather, suppose that your mom’s Springing Power Of Attorney includes the common requirement that her incapacity be certified by two licensed physicians. At best, that will likely delay your ability to act on her behalf by several days. At worst, the physician may not agree with your lay assessment. Or mom may not be willing to go to the doctor just to risk being told she’s no longer competent!

Example 3a. Continuing the prior example, suppose that after being told by the bank that they will not act until receiving a physician’s certification, you immediately call up mom’s doctor, who agrees to see you both first thing the following morning.

But lo and behold, and as luck would have it, the next morning, mom is having one of her “good” days. She recalls the names of her children, the President, and even the date, all with ease. Thus, while privately your mother’s physician sympathizes with your predicament, they refuse to certify her as incompetent.

And now, to make matters worse, your mother is so insulted by your insinuation that she is no longer competent enough to handle her own affairs – even though in reality, she clearly is not – that she refuses to execute any sort of new agreement that would grant you authority over her accounts now!

This, of course, was just a hypothetical example. But sadly, this type of thing plays itself out every day in countless homes throughout the country.

The (Benefits Of A) Durable Power Of Attorney

One tool that can be used to effectively combat the risks associated with a Springing Power Of Attorney is another “flavor” of Power Of Attorney, known as a Durable Power of Attorney.

Unlike a regular (i.e., nondurable) Power Of Attorney which ceases to be effective once the Principal becomes incapacitated, or a Springing Power Of Attorney, which may only become effective after such an event, a Durable Power Of Attorney is effective upon execution and continues to remain in effect even after the Principal becomes mentally or physically incapacitated.

By default, however, Powers Of Attorney (other than Health Care Powers Of Attorney [a.k.a. Healthcare Proxies]) are nondurable in nature. Thus, in order to make a Power Of Attorney durable - given the risks involved, as a Durable Power Of Attorney then stays in effect "forever," or at least until the Principal dies, or revokes it – the document must include specific language, generally determined by state law, to stipulate that it will be durable.

While both Durable Powers Of Attorney and Springing Powers Of Attorney can allow a family member to step in and manage an account after the Principal is incapacitated, Durable Powers Of Attorney offer several advantages over the latter.

First, since Durable Powers Of Attorney are in continuous effect after execution, there is no triggering event that must first be “proved” before the Attorney-In-Fact can act. Thus, problematic delays caused by disagreements over whether the triggering event has occurred, and thus making the Attorney-In-Fact’s authority effective, can be avoided.

An additional benefit of a Durable Power Of Attorney is that, since it allows the Attorney-In-Fact to begin acting as soon as the document is executed (at which point, the Principal must be of sound mind and body), it can give the Principal an opportunity to give their Attorney-In-Fact a trial run of sorts.

Example #4: Martha names her daughter as her Attorney-In-Fact via a Durable Power Of Attorney. While Martha is still capable of making sound decisions, she can have her daughter begin to manage her affairs. If questions arise during this time, Martha should be able to help guide her daughter, effectively enhancing the degree to which she will be able to stand in for Martha when/if the need arises. Similarly, if things go well during this “trial run,” Martha can rest easier knowing that she’s made the right choice with respect to her Attorney-In-Fact. And on the off chance it doesn’t go so well, Martha can make a change while she is still competent to do so.

Financial Institutions May Have Their Own Requirements Regarding Powers Of Attorney

Having a valid Power Of Attorney is an integral part of just about every estate plan. But unfortunately, not every financial institution, such as a bank or brokerage firm, will honor the generic(ish) document drafted by an attorney. Instead, absent a court order, the institution may require the Principal to complete the financial institution’s own standard Power Of Attorney form. Other times, the institution will accept the document, but only following a(n often) lengthy review by its legal department. Clearly, either of these situations could become problematic.

As such, one of the most important aspects of making sure that a loved one will be able to manage an account on your behalf is to actually find out what your financial institutions’ policies are. If an institution requires its own Power Of Attorney form, be sure to complete that form while you are still capable of doing so (i.e., of sound mind and body).

Alternatively, if the financial institution will honor your own Power Of Attorney document, consider submitting the Power Of Attorney to the institution as soon as possible (i.e., while the Principal is still healthy and the document isn’t actually “needed”). This way, if there is any sort of legal review of the document that must be conducted prior to its approval for use at the institution, that process can be completed before the Attorney-In-Fact’s services are needed. And if, for whatever reason (e.g., a signature is ineligible, a page on the copy is cut off, etc.), the institution has any problems with the document, those problems can be addressed now.

All too often, Powers Of Attorney are only presented to financial institutions once the absolute need to use the powers conveyed by the document has materialized. By that time, however, any issues with the document may require a court intervention to resolve, and any delays preventing the Attorney-In-Fact from acting could be costly.

Option #3: Create A Revocable Living Trust And Name A Trusted Family Member As A (Co-)Trustee

A third potential option for allowing a trusted family member to aid in the management of an account is to create a Revocable Living Trust, and to “fund” that trust with the account(s) in question.

A Revocable Living Trust, sometimes referred to as an “Inter Vivos Trust” (where “inter vivos” is Latin for “between the living”), is a legal entity that is created upon the execution of the trust document that provide for a trust relationship between the trust creator and a trustee of the trust. In general, such trusts provide for the benefit of the creator during the creator’s lifetime and are drafted in a manner that allows their terms to be changed during the creator’s lifetime, or even for the trust to be terminated altogether (thus being “revocable”).

Notably, Revocable Living Trusts, like all trusts, must be administered by a Trustee. And similar to the fiduciary duty owed to a Principal by an Attorney-In-Fact upon the execution of a Power Of Attorney, the Trustee of a trust is also a fiduciary and must legally act in the interest of the trust beneficiaries.

Revocable Living Trusts offer several advantages when compared to Powers Of Attorney. For one, a valid Revocable Living Trust is less likely to be flat out rejected by a Financial Institution, because once a Living Trust is created it is its own ongoing entity, and if it has taken legal title of property, by definition the trust is active and controlling with respect to that property (which means the institution doesn’t have to scrutinize it like a Power of Attorney that may or may not actually still be effective when the time comes). And, since the Revocable Living Trust must become the actual owner of the assets in order to work (more on this in a moment), if an existing financial institution has any issues with your trust paperwork, etc., you should be able to find that out before it becomes an issue (as it will instead become an issue when the account is opened and/or when property is funded into the trust in the first place).

Compared to using a Power Of Attorney, another advantage of using Revocable Living Trusts to allow a trusted family member to gain access to an account for management purposes is that the powers given to the trustee of a Revocable Living Trust don’t end at the creator’s death. Rather, the Revocable Living Trust lives on (though generally now as an irrevocable trust, since the creator is no longer alive to revoke it), allowing the Trustee to continue to administer trust property going forward. Thus, such revocable living trust property is able to bypass the probate process and can virtually immediately be transitioned for use by the next-in-line trust beneficiaries. Alternatively, the trust can terminate after the death of the creator, and its assets distributed outright the remaindermen.

Co-Trustees Vs. Successor Trustees Of Revocable Living Trusts

Oftentimes, Revocable Living Trusts are drafted such that the creator of the trust serves as the sole trustee of the trust and retains complete authority of the trust’s assets. Which makes sense, since the revocable living trust is funded with the creator’s own assets, for the creator’s benefit, akin to the creator owning those assets outright. As ultimately, the whole point of a revocable living trust is to ensure that a third party can control the assets if/when/as needed… but not necessarily to relinquish control upfront. Thus, it’s common that the creator retains control as trustee until such time as he/she resigns from that position, or is no longer able to do so due to death or incapacity. Only at that time would the “back-up” next-in-line trustee, known as a Successor Trustee, assume responsibility for administering the trust and its property.

While this sort of structure can sound appealing to the trust creator, since it allows them to “hold on to the reigns” right up until they are no longer able to do so, it can result in similar problems as a Springing Power Of Attorney. For instance, in order for the Successor Trustee to assume the Trustee role in the event of the original trustee’s incapacity, the original trustee must generally be “proved” incapacitated, often by the same as-certified-by-two-licensed-physicians test. This can lead to critical delays in access to funds at a time when they are desperately needed, where the Successor Trustee needs to step in but doesn’t yet have the requisite incapacity certification to do so.

To that end, instead of having the to-be-responsible-in-the-event-of-incapacity party serve as a Successor Trustee, it may be better to name them as a Co-Trustee (effective immediately, even while the creator is still healthy and able to manage his/her own affairs), and to further structure the Revocable Living Trust such that each Trustee can act independently of the other. In doing so, the trusted person will legally have access to administer the trust assets from “day one,” but other than perhaps signing a few account opening forms, they won’t have to use their powers until the time is necessary.

When that time comes, however, there should be no delays or gaps in access to trust assets, because a Co-Trustee already has access to those assets. There’s nothing new for the financial institution to review!

Of course, granting a Co-Trustee power immediately does create the risk that a Co-Trustee has power immediately... and may use it irresponsibly. However, like the Durable Power Of Attorney, using a Co-Trustee setup with a Revocable Living Trust can allow the creator to “test drive” the Trustee first. If unforeseen problems arise, or the job seems overly burdensome, the creator can always make use of the “living” part of the Revocable Living Trust and use their powers to “vote” the current Co-Trustee off of “Trust Island,” and name a new Co-Trustee.

But ultimately, if the creator trusts their Co-Trustee enough to be responsible for the trust property while the creator is incapacitated and can’t oversee their activities, it ostensibly shouldn’t be a problem for the Co-Trustee to have powers while the creator can monitor the situation. Yet, in the meantime, the trust creator is still more protected, because a Co-Trustee may have immediate access to trust property, but must still use it for the creator’s benefit, and cannot use the assets for the Co-Trustee’s own benefit, nor are the trust assets subject to the Co-Trustee’s own creditors (as would be the case if the Co-Trustee were simply added to the property title directly).

Revocable Trusts Must Be Funded (In Advance Of Incapacity) In Order To Work

One of the most important aspects of using a Revocable Living Trust to allow a trusted family member to help manage assets in the event of incapacity is that the trust document (and thus the trustee) only controls assets for which the trust itself is actually the owner.

To that end, after a Revocable Living Trust has been created, it must be “funded” in order for it to be effective. In general, “funding” a revocable living trust means opening new accounts at financial institutions, in the name of the trust, and transferring assets from existing accounts into the newly-established trust accounts. For other assets, such as real estate, it means changing the title of the asset to be held in the name of the Revocable Living Trust (and not directly in the creator’s own name).

The caveat to funding revocable living trusts, though, is funding must occur while the trust creator is of sound mind and body themselves… since they must be the ones to effectuate the transfer of their existing property into the trust in the first place.

Even a Co-Trustee is of little to no use if the revocable living trust isn’t funded before incapacitation, because again, even a trusted-family-member Co-Trustee powers only extend to trust assets. And prior to being transferred into the trust/retitled, assets are not assets of the trust!

Thus, in the event of incapacity, if assets are not already inside of the Revocable Living Trust, it will likely require either a court order or the act of an Attorney-In-Fact via a Power Of Attorney that grants them gifting powers (which in some states, often requires a special rider to be attached to the Power Of Attorney) to make the transfer into the revocable living trust in the first place. And frankly, at that point, the Attorney-In-Fact could just deal with the assets themselves, making the Revocable Living Trust somewhat useless (at least for incapacity planning purposes, though it would still enable the assets to bypass probate and allow trustee-led post-death control).

The three options listed above – joint ownership, Powers of Attorney, and Revocable Living Trusts – are some of the most commonly used tools when it comes to planning for incapacity, but they are no means the only options. Other possibilities include the use of irrevocable trusts, which provide the added benefit of enhanced creditor protection, or partnership entities that enable a family member to manage the investable assets of other family members together in a combined pool.

Ultimately, like most planning scenarios, figuring out the best way to deal with a potential incapacity and how to maintain seamless access to, and management of accounts must be determined on a case-by-case basis. Though commonly, the “answer” is more than just a single solution.

After all, certain assets cannot be moved into a Revocable Living Trust during the trust owner’s lifetime to begin with, and thus, cannot be controlled by the Trustee of the trust via their trust-given powers. Similar to the joint account “solution” discussed above, IRAs and other retirement accounts are a prime example of this problem, as transferring such assets into a trust would be treated as a taxable distribution of the retirement accounts. Similarly, retitling an annuity into a trust can also trigger a taxable account, although annuities generally can be transferred to and owned by a revocable living trust, as long as it has the same tax ID (i.e., Social Security) number as the original creator (which is typically the case for a revocable living trust).

Still, though, what this means is that when planning for incapacity, often some of the largest assets in an individual’s estate cannot be adequately addressed with a Revocable Living Trust. Rather, a Power Of Attorney is often the only solution. As a result, incapacity planning for multiple types of different accounts and assets is often a blend; for instance, it may be that a Revocable Living Trust is used for bank and taxable brokerage assets, while a Durable Power Of Attorney is used for retirement assets.

The key, however, is to plan in advance, so that when the time comes, there is minimal disruption to one’s finances. And, of course, to make sure that what happens is decided by the creator’s own choice, and not in a courtroom by a judge who has to step in due to a failure to plan in advance.