Executive Summary

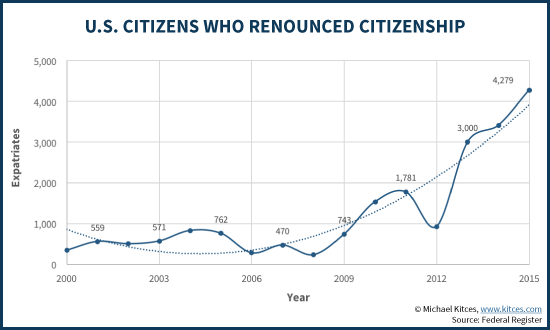

Given the especially contentious election cycle, many people have stated that if their opposing party's candidate wins, they're seriously thinking about leaving the country. And in point of fact, the number of people who renounce their U.S. citizenship actually has been on the rise in the past 15 years, though it is still a fairly low number in total.

However, the reality is that for those with a substantial net worth - in excess of $2M of total assets - and/or those who have an especially high income, their renunciation of citizenship can subject them to the so-called "Covered Expatriate" rules, which include a deemed disposition tax that can cause the individual's entire net worth to become immediately taxable upon leaving... including triggering all unrealized capital gains, and the instant deemed liquidation of all their IRAs!

In this guest post, Raoul Rodriguez - a specialist in cross-border financial planning (particularly between the US and Mexico) - discusses the tax issues involved in determining whether someone actually would be a Covered Expatriate if they decide to renounce their U.S. citizenship, the deemed disposition exit tax and other tax complications that may arise, and the planning opportunities that are available to at least try to mitigate the consequences.

So whether you have a client who is seriously talking about leaving the U.S. if the "wrong" candidate wins the presidential election, or you simply have clients who wistfully suggest they "might" someday leave, hopefully this article will be helpful in getting you up to speed about how the rules actually work... just in case it ever does become necessary to know!

Many people suggest that they are so fed up with the current political situation in the United States that they are ready to renounce their U.S. citizenship and move abroad. They would not be alone. Growing numbers of people are giving up their citizenship. Where once only a handful renounced their passports per year, nearly 4,300 did so in 2015 — and this trend continues to accelerate. But to do so implies real tax and financial planning consequences.

This article will explore the pros and cons of such a move from a tax perspective and as well as provide some planning ideas for those who are still seriously considering the option.

The first question to answer is: Can you legally give up your citizenship?

This is not such a silly question, as many countries of the world do not recognize that this is even a possibility. That being said, according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – a document from the United Nations that is not legally binding, but does have moral force for participating countries – we all have the right to renounce our current citizenship. Article 15(2) states that:

“No one…..shall be denied their right to change his nationality.”

In the U.S., one can lose U.S. citizenship by voluntarily committing one of several expatriating acts with the intention of giving up U.S. citizenship, including fighting in the armed services of a foreign state against the U.S., or committing an act of treason against the U.S. government.

In addition, U.S. citizens can also choose to outright renounce their citizenship. Specifically, under Section 1481(a)(5) of Title 8 the U.S. Code, one can lose their U.S. citizenship by:

“Making a formal renunciation of nationality before a diplomatic or consular officer of the United States in a foreign state, in such form as may be prescribed by the Secretary of State;”

In short, the US allows its citizens to renounce their citizenship, or “expatriate” (the act of withdrawing allegiance to a country).

Interestingly, expatriation laws apply not only to U.S. citizens but, as noted in IRC Section 877(2), also to long-term residents (i.e., lawful permanent residents in at least 8 of the past 15 years) who want to give up their “green card” status. In other words, these rules also apply to many foreigners that have lived legally in the U.S. and want to return home.

Expatriation is permanent, and irrevocable, and after doing so, the taxpayer would be treated (with important exceptions noted below) as a non-resident alien (NRA). In fact, because renouncing citizenship and expatriating forfeits an individual’s rights as a U.S. citizen, the act of renunciation itself must take place before a U.S. diplomatic or consular office outside the U.S. (i.e., renunciation can only take place while abroad). Notably, this also means someone who plans to expatriate should secure citizenship for another country/nationality, or risk becoming “stateless” and be unable to obtain rights of access to most countries.

The rules to acquire foreign citizenship are specific to each country, but some ways it can be acquired include: by being born in that country; by having parents or grandparents from that country; by marrying a citizen of that country; by having citizen children in that country; by living in that country’s jurisdiction for a certain (typically, multi-year) period of time; or by purchasing real estate or otherwise investing substantial assets in the foreign country.

Adverse Tax Consequences Of Renouncing For U.S. “Covered Expatriates”

The Heroes Earnings Assistance and Relief Tax Act (HEART) of 2008 set new tax rules for expatriation (those who expatriated prior would be subject to a different set of rules). Not everyone who expatriates is treated the same for tax purposes. Certain taxpayers can more easily renounce their citizenship or U.S. residence status, while others, known as “Covered Expatriates” face more stringent and expensive tax consequences.

Who Is A “Covered Expatriate”?

As of 2016, a Covered Expatriate is an individual with a net worth of $2 million or more, and/or an average annual net tax liability for the preceding 5 years of $161,000 or more (indexed annually for inflation).

Notably, the authorities look at the individual’s tax liability, not just his/her annual income. Thus, a taxpayer could have high gross income (hundreds of thousands of dollars or more) that was adjusted down due to exclusions, deductions, or mitigated by subsequent tax credits. For example, a high income earner working abroad might lower the U.S. tax burden significantly by use of the foreign earned income exclusion and foreign tax credits. In addition, other planning work can proactively take place to reduce the net worth and tax liability exposure.

In the year of renunciation, the taxpayer will need to file a regular Form 1040 to report the partial tax year from the beginning of the year to the date of renunciation, and a Form 1040NR to cover income for the remainder of the year. Since 2008, an expatriate must also attach Form 8854 to their final 1040 filing, which the government uses to determine if the individual will be treated as a “Covered Expatriate” (and also serves as notice to the U.S. Treasury Department of the new tax status).

In the case of married couples, it’s important to recognize that there is no such thing as a joint Form 8854. Therefore, married couples will need to each qualify individually under the net worth and income tax liability tests. For the net worth test of each married individual, who owns what should be determined according to state laws. For purposes of the average tax liability test, though, if a couple files jointly, the amount reflected on the return is not divided by 2 but instead under IRS Notice 97-19 is considered in its entirety for each individual.

Exceptions To Covered Expatriate Treatment

For those who meet the above net worth or tax liability requirements and would be treated as a Covered Expatriate, IRC Section 887A(g)(1)(B) states that it is still possible to avoid Covered status by meeting one of the following:

- If the taxpayer is a dual national of the country in which she was born AND she has not lived more than 10 out of the last 15 years in the U.S.;

- The individual originally expatriated before she was 18.5 years of age, and did not live in the U.S. for more than 10 out of the last 15 years.

(It’s important to note that long-term resident aliens may also be subject to the Covered Expatriate rules if they wish to renounce their green-card status. However, the Covered Expatriate rules will still not apply if the individual was a long-term resident for eight or fewer years out of the last 15. Or if any of the other exceptions above are met.)

Regardless of the exceptions, anyone expatriating must also certify that they have been compliant with U.S. tax law for the previous five years. Lack of full and accurate compliance, or failure to certify such compliance, results in an automatic designation as a Covered Expatriate, even when other exemptions might otherwise apply.

Exit Taxes That May Apply To Covered Expatriates

The 2008 HEART Act established several new taxes that apply to Covered Expatriates when they renounce citizenship:

- A deemed disposition (“exit”) tax

- A gift/estate tax

- An inheritance tax applicable to U.S. beneficiaries receiving assets from certain expatriates or their estates.

Deemed Disposition (Exit) Tax

Covered Expatriates are required to pay a deemed disposition or “exit tax” upon renouncing their citizenship.

The tax is determined by assuming that most property interests are “marked to market”, and then taxed as if they were sold on the date immediately prior to expatriation. These deemed sales (and the phantom capital gains they trigger) are then reported on the corresponding forms and schedules of form 1040.

Disposition rules stipulate that all deemed income retains its original character, which means that long-term capital gain property is taxed at favorable rates, ordinary gains at ordinary income tax rates, etc. Capital gains on property sold is reported on Schedule D, depreciated property sales are reported on form 4797, and gains on personal property are reported on form 8949.

Importantly, for 2016, the first $693,000 (indexed for inflation) in deemed gains are exempt from this tax, though this exception only applies against deemed capital gains, and not against the income from a deemed distribution of an IRA and/or other tax-deferred account.

What Assets Are Considered When Determining The Deemed Disposition Gains?

For purposes of determining gains for the deemed disposition tax, it is essential to know what property is included (and the associated basis).

Notice 2009-85, Section 3A states that the expatriating taxpayer includes all property where he or she:

“…owns any interest in property that would be taxable as part of his or her gross estate for Federal estate tax purposes under Chapter 11, Subtitle B of the Code as if he or she has died on the day before the expatriation date as a citizen or resident of the United States.”

In other words, all worldwide assets are included as part of the calculation. This is notable not just because of the sheer scope of the rule, but also because deemed dispositions of foreign property will not generate a foreign tax credit (just a U.S. tax liability), and property that is deemed disposed at expatriation is not eligible for any marital, charitable, or qualified domestic trust deductions that might have otherwise applied if held until death.

Furthermore, consideration must be given to gifts of certain assets and interests made three years prior to expatriation, since these might be clawed back into the taxable base.

Account Types That Do NOT Trigger A Deemed Disposition On Expatriation

Just to make things more complicated, there are three exceptions to the mark to market rules noted in IRC Sections 877 (a), (e), and (f):

- Eligible deferred compensation agreements

- Ineligible deferred compensation items

- Interests in non-grantor trusts

Under IRC Section 877A(d)(3), eligible deferred compensation agreements, such as deferred bonus plans, or more commonly 401(k)s, are not taxed on expatriation but are instead taxed when paid out, generally at 30% (and notably, per IRC Section 877A(d)(3)(B)(ii), even if a lower tax rate might have applied to the foreign citizen with U.S. investments under a tax treaty, after renouncing citizenship, the 30% withholding rate will always apply).

Notably, in the case of Traditional IRAs and similar specified tax-deferred accounts, and Roth IRAs, these will be treated as if a distribution of the entire account was made on the day prior to expatriation (though, under IRC Section 877A(e), early distribution penalties will NOT apply). However, deferred compensation plans (including non-qualified deferred compensation, the salary deferral component of a 401(k) plan, and certain non-grantor trusts) are only taxed in the future when liquidated (as discussed in a later section).

So-called ineligible deferred compensation plans, such as unfunded and unsecured promises to pay income in the future, have much more complicated formulas. The tax is applied on the present value of the deferred compensation pursuant to Notice 2009-45 and other treasury regulations.

Under IRC Section 877A(f)(3), non-grantor trusts are taxed when payments are eventually made, and again are generally subject to a 30% tax.

Gift And Inheritance Taxes

Covered Expatriates are taxed differently than “run-of-the-mill” non-resident aliens when it comes to making gifts or bestowing an inheritance on U.S. persons, called “Covered gifts or bequests” under IRC Section 2801(a).

In such situations, any gift or estate taxes are automatically applied at the highest marginal bracket (above exemption amounts) for gifts or estate tax purposes (currently a maximum 40% rate).

In addition, by default the tax is actually assessed twice – as a gift/estate tax paid by the donor or estate, AND a separate “inheritance tax” that is paid by the donee. However, if the donor files a timely gift tax return (or the estate a timely estate tax return), then the recipient avoids the subsequent tax under IRC Section 2801(e)(2). If the corresponding gift or estate tax returns are not filed in a timely manner, the transfer will be taxed twice.

Expatriation And Social Security Benefits

For those who have paid into the U.S. Social Security system while U.S. citizens, it’s notable that Social Security benefits are still available, even to those who expatriate. The Social Security payments can be deposited into foreign bank accounts in most (though not all) countries. However, once citizenship has been renounced, no further benefits will accrue (i.e., whatever benefit has already been earned will simply be ‘locked in’ at that point).

In the case of Medicare benefits, eligibility remains even for those who expatriate, though in practice will be used sporadically, if at all, as Medicare payments are generally only available for services rendered in the U.S. Though a former U.S. citizen who has qualified for Medicare could come back periodically to the U.S. for services already earned, as long as he/she otherwise complies with the rules for former citizens returning to the U.S (generally limited to no more than 30 days in a year for the first 10 years after renouncing).

Election To Defer

A Covered Expatriate may elect to defer tax due on the deemed sale of assets. Tax will be deferred until the property is actually sold or the taxpayer dies. However, consideration must be given to the fact that:

- Security must be provided

- Interest will accrue on deemed tax amounts

- Taxpayer must appoint a U.S. agent

- Treaty rules must be irrevocably waived if they preclude assessment of a given tax

Limitations On Returning To The U.S. After Expatriation

When discussing renunciation, it’s crucial to be aware of the Reed Amendment, which states:

Any alien who is a former citizen of the United States who officially renounces United States citizenship and who is determined by the Attorney General to have renounced United States citizenship for the purpose of avoiding taxation by the United States is inadmissible.

Denying one entry back into the U.S. forever is quite harsh. However, regulations have never been published for the Reed Amendment, and it is generally considered poorly written and unenforceable. I am unaware of any actions taken pursuant to the Reed Amendment. Subsequent legislative attempts have been made to limit access to the U.S. by expatriates or impose additional punitive measures, but all have been unsuccessful to date.

While an outright ban on returning to the U.S. is not current practice, as mentioned previously, current legislation does limit the time one can be in the U.S. after expatriation to no more than 30 days per year for ten years following expatriation. These 30 days may be increased another 30 if you are performing personal services for a non-related employer.

If the taxpayer exceeds this threshold, she is taxed as if she were again a U.S. person for that entire tax year (which means the U.S. will tax all of his/her income, worldwide, for the year).

U.S. Taxation Of Non-Resident Aliens (NRAs)

After reading all of the above, you may wonder if there really are any tax advantages to renouncing U.S. citizenship. Unbeknownst to many, the U.S. is in fact one of the principal offshore tax havens in the world. Expatriates, now NRAs (if they renounce citizenship and leave the U.S., but maintain assets in the U.S.), can take advantage of the favorable tax laws designed with the principal intent to encourage foreign investment in this country.

What is Subject to Taxation as a NRA?

NRAs are subject to U.S. income tax on a limited basis compared to U.S. citizens. Specifically, under IRC Sections 871(a), 871(b), 881, and 882(a), the only income that is taxed is “effectively connected income” (ECI) to a U.S. trade or business, and “income that is fixed, determinable, annual or periodical (FDAP)” that arises from U.S. sources.

Furthermore, the U.S. tax convention and totalization agreements signed with countries around the world will often reduce or eliminate income, estate, and Social Security taxes below statutory amounts. Thus, NRAs with U.S. assets are only taxed in a limited manner on their U.S. assets (while their non-U.S. assets remain outside the U.S. jurisdiction), even as U.S. citizens are taxed on worldwide income (U.S. and non-U.S. assets).

Given that many NRAs own real estate in the U.S., it is important to touch on this asset in particular. Income from real estate activities is considered ECI. Rental income will be taxed normally, and the property needs to be depreciated, per existing U.S. tax law. Upon sale of the property, certain withholding provisions apply pursuant to the Foreign Investment in Real Property Act (FRIPTA). Accordingly, the transaction may be subject to 10% withholding on the value of the transaction (not 10% of the gain, but 10% of the entire transaction price!). The gain is calculated normally, and any portion of the 10% withholding above and beyond the actual tax due is refunded to the NRA after the 1040NR is filed. In other words, there is no favorable capital gains treatment on real estate transactions.

However, beyond real estate transactions, there are NO capital gains taxes on the disposition of assets that are not effectively connected to a trade or business conducted in the US. The most important example are investments by NRAs in securities which when sold will not generate a capital tax obligation (though the NRA may still face capital gains taxes in his/her home country). In other words, there are no U.S. tax costs for buying and selling stocks, bonds, options, etc. (neither long- nor short-term). Interest paid by U.S. banks and on debt instruments issued after 1984 is also U.S. tax-free.

Further, dividends paid to NRAs are subject to 30% withholding, though tax treaties often reduce this burden (even for those who renounce their citizenship, for any dividend income received after expatriation). For example, Article 10 of the U.S. Mexico Tax Convention states that Mexican tax residents with U.S. dividend income pay only between 5-10% tax on dividend income regardless if the dividend income is U.S. tax qualified or not.

It is also important to note that the general estate tax rules that apply to NRAs are not modified for those that expatriate. Most notably, NRAs only have an exemption equivalent of $60,000 under IRC Section 2102(b)(1) (versus the $5.45 million that is available to U.S. persons in 2016) and regular estate tax rates apply to amounts above the exemption amount. The estate tax is applied on most U.S. situs assets including personal property, business interests, real estate and securities held in investment accounts. Notable exceptions are proceeds from life insurance contracts and deposits in bank accounts in the U.S. which are excluded from the gross estate of NRAs for estate tax purposes.

Imagine an investment world with practically no capital gains taxes, no tax on interest, and low taxes on dividends. Add to this the possibility of eliminating or significantly reducing the tax compliance burden.

This world does exist! That is what many people who have chosen this path have seen as a real possibility. Whether expatriating makes sense from a financial perspective will depend on several factors, including the time to recover deemed taxes paid by future good investment results, tax rates in the foreign country, and proper pre- and post-expatriation planning.

What About Taxes In The Adopted Country?

There is a principal in tax law that states that one needs to be a “tax resident” somewhere. In practice, there are three general categories of foreign tax jurisdictions to choose from: no tax, low tax, and everyone else.

“No tax” jurisdictions do not impose any income tax at all on their residents. Two popular countries for expatriates in this category are the Bahamas and Monaco.

“Low tax” jurisdictions impose tax only on in-country-sourced income. Income earned outside the jurisdiction is not subject to local income taxes (and as noted earlier for U.S. assets, may not be taxed in the U.S. either!). Examples of countries in this category include many jurisdictions popular with US expatriates, including Costa Rica, Panama, and Singapore.

Most other countries around the world will simply have their own “normal” tax rules for tax residents of their jurisdiction, which may include tax rates that are higher or lower than the U.S., and may also tax the resident on a worldwide basis. Though even in other relatively high tax countries, local tax law might provide important exemptions, allow for more creative tax deferral and gifting strategies, and may have less stringent tax compliance regimens.

Regardless of which jurisdiction one chooses, careful tax planning of not only the process of leaving the U.S., but tax emigrating into the new jurisdiction, needs to take place prior to expatriation.

U.S. Planning Opportunities And Considerations

The best of all worlds, by far, is to avoid being treated by the IRS as a Covered Expatriate. If the taxpayer can meet certain tests explained above, then life will be immensely simplified upon expatriation. The act of expatriating will still mean finding a new country of citizenship and returning to the U.S. might require a visa, but the additional deemed disposition and other tax consequences won’t apply for someone who chooses to renounce citizenship.

In fact, the tax consequences of trying to depart as a Covered Expatriate are so severe for many, that anyone who is considering whether to renounce U.S. citizenship would be well served to get themselves below the net worth or income tax liability thresholds, if possible.

For example, direct gifting can help lower the taxpayer’s net worth to amounts that would allow the taxpayer to avoid being considered a Covered Expatriate. This may be especially appealing for gifting U.S. property, which will no longer be eligible for the $5.45M unified gift and estate tax exemption after expatriating. However, the taxpayer need not only make direct gifts, but could also consider using trusts prior to expatriation to make completed gifts. Pre-expatriation trusts must take extreme care in how they are drafted so as not to inadvertently cause assets held in trust to be considered beneficial interests of the grantor or to be otherwise considered as owned by the grantor under IRC Sections 671 through 679, which could cause inclusion in the net worth calculations and possibly cause deemed disposition taxes. Further, as indicated by Notice 2009-85 which states IRC Section 684 may apply, care must also be taken not to cause the U.S. trust to be considered a foreign trust upon expatriation of the grantor, since this may also trigger capital gains taxes on appreciated property contributed to the trust (see also: IRC Section 7701(a)(31)(b) and Treasury Regulation 301.7701-7).

If Crummey powers are included in the trust provisions, the Covered Expatriate could continue to make gifts of up to $14,000 per beneficiary. Since the Crummey gifts by a Covered Expatriate are not considered for estate or gift tax purposes, there are no Generation-Skipping Transfer (GST) Tax issues either when a pre-expatriation trust is funded in this manner. Appropriately drafted pre-expatriation trusts can still allow the grantor to act as trustee.

The taxpayer could also use traditional planning techniques to discount the value of assets, both to facilitate gifting (e.g., to get under the Covered Expatriate income threshold) or to reduce the valuation and capital gains exposed for the deemed disposition tax itself, but the IRS has often challenged valuations and IRC Section 2704 Treasury Regulations have been proposed that may further limit flexibility in this area. Examples could be the creation of a Family Limited Partnership (FLP) or other fractional ownership arrangements for real estate assets.

Other gifting strategies might include the establishment of a Donor Advised Fund (DAF), assuming someone has charitable intent in the first place. Low cost basis property should be considered a high priority for any charitable gifting, as it not only leverages the charitable deduction, but avoids a capital gain that would be taxed as a deemed disposition.

Married couples may want to take advantage of the fact that gifts between spouses are tax free under IRC Section 1041, and use intra-couple transfers to clarify or arrange each person’s net worth with a view to have both spouses come in under the threshold of the net worth test. If they have been filing joint returns, they may want to consider changing status to married filing separately, which may increase the possibility of passing the average tax liability test by roughly splitting their tax liability between the two returns (with the caveat that it may increase their individual tax liabilities compared with filing jointly, given the tax disadvantages of married filing separately).

Life insurance could be purchased and placed in the trust for the benefit of U.S. persons. However, the taxpayer should consider buying the life insurance prior to leaving the U.S. since life insurance costs are often more expensive abroad and policy riders and flexibility may be limited in foreign policies.

For someone who cannot bring themselves below the Covered Expatriate thresholds, other tactics may at least help reduce the consequences of the deemed disposition exit tax.

Consideration, in some instances, should be given to actually selling capital gain property instead of paying the deemed disposition taxes. The reasoning here is that the deemed disposition or exit tax applied by the U.S. will not generate a foreign tax credit in the other jurisdiction of tax residence, since it is not technically an income tax. Then, in the future, the foreign jurisdiction might seek to tax the sale of those same assets when they are truly sold. In other words, the taxpayer could pay taxes twice, once on the deemed disposition in the U.S., and then again when sold, to the foreign country. If the taxpayer really wants to hold the assets, they could be repurchased after expatriation.

Taxpayers should probably consider selling the main home in order to take advantage of the exclusion under IRC Section 121 ($250,000 if single or $500,000 if filing a joint return), since it is not clear if the exclusion would be available after expatriation for a U.S. principal residence (and likely wouldn’t be available to minimize capital gains taxes in the foreign country of new citizenship).

Those expatriating may want to look into the possibility of a reverse rollover of Traditional IRA assets into a 401(k) if available and allowed, as 401(k) assets are not treated as a deemed disposition immediately upon expatriation (and instead can remain tax-deferred until subsequent liquidation). Notably, though, it only helps to transfer back the deductible, pre-tax, contributions and related earnings, which are eligible for the more favorable treatment. Conversely, be especially cautious not to roll over a 401(k) to a Traditional IRA, as the IRS will consider assets now held in the Traditional IRA to be treated as a deemed disposition upon expatriation.

In certain circumstances, the taxpayer may consider converting a Traditional IRA to a Roth IRA over a period of years prior to expatriation if the taxpayer has owned a Roth (any Roth) for more than five years and the Covered Expatriate is 59 and ½ or older upon expatriation. Like traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs will be considered as distributed on the day prior to expatriation (although the funds might not have left the account). Unlike Traditional IRAs, however, the putative distribution will not be a taxable event, as it satisfies the requirements to be a “qualified distribution” if the holding period and age requirements above are met. By converting the Traditional IRA over a period of years prior to expatriation, the taxpayer spreads the tax burden due to conversion among several years. Another possible advantage is that by spreading the taxable income over several tax periods, the taxpayer may avoid being kicked into a higher tax bracket if one large conversion took place in a single year. Finally, income within the Roth IRA continues to grow tax free and may be received without a US income tax consequence after expatriation (though distributions from the Roth IRA may be subject to withholding up to 30%, the taxpayer could file a 1040NR and request a refund for amounts of excess withholding).

In addition, converting a Traditional IRA and paying taxes may, in a perverse way, help a taxpayer avoid the net worth hurdle of $2 million, to the extent that the Roth conversion triggers an immediate tax bill that must be paid. In other words, when a person is on the threshold of meeting the $2 million test, a large tax hit (on a traditional IRA tax bill that would have to be paid someday, anyway) might tip the net worth below the amount that would cause a taxpayer to be considered as a Covered Expatriate. On the other hand, it’s worth noting that same large Roth conversion tax liability might cause the same person to cross over the five-year average tax liability test. This balancing act that needs to be taken into consideration.

Given that the gross estate of NRAs only enjoys a $60,000 exemption, consideration should be given to the pros and cons of holding U.S. interests within foreign entities (similar to how U.S. citizens may hold assets in U.S. entities, like an LLC); by using a foreign entity, the U.S. asset may be treated as a foreign business asset, reducing exposure to U.S. estate taxes after expatriation. Additionally, life insurance could be purchased to cover potential U.S. tax liabilities, especially in light of the fact that under IRC Section 2105(A), U.S. life insurance proceeds are not includable in the gross estate of the NRA decedent.

New U.S. estate planning documents need to be drafted with NRA provisions.

Conclusion

Some jurisdictions around the world provide for low tax rates and compliance burdens, especially as compared to what we face in this country, which can make renouncing U.S. citizenship an enticing proposition (and if you can’t stand the politics, maybe leaving is an added bonus!). In addition, the U.S. gives favorable tax treatment to foreigners that invest in this country — treatment more favorable than the tax rates that generally apply to citizens and residents. This can result in tax liabilities which can make it appealing to keep some assets in the U.S. even after expatriating.

However, it is strongly recommended that careful pre-expatriation planning take place, with a view to eliminate or diminish as much of the U.S. tax and travel restrictions that apply to some of those giving up their citizenship or long-term residency. This is especially true for those individuals who have sufficient net worth or income (tax liability) to be treated as Covered Expatriates.

Finally, the tax consequences of the other jurisdiction of choice must also be analyzed as part of the plan — or one risks jumping from the frying pan into the fire!

As with any discussion on taxes, the taxpayer should consult with her CPA and attorney before making any decision. This article is only meant to highlight some of the issues and possibilities and not meant to provide specific tax or legal advice.