Executive Summary

While the accelerating pace of technological change has many industries buzzing about the risk of disruption – including the world of financial advice – in practice, many forecasted disruptions never come to pass. Sometimes, it’s because the new “innovation” isn’t really all that much better than the status quo – at least, not better-enough to convince people to make a change. In other cases, it’s simply because it’s a new solution that consumers aren’t yet accustomed to paying for.

In fact, often some of the most disruptive business models are the ones that succeed through the use of cross-subsidies – giving away “for free” something that consumers were previously paying for, because there’s an opportunity to make money in other ways instead. Or viewed another way – not every part of every business model must be compensated, as long as there’s at least one component that is valuable to someone who’s willing to pay enough to make it economically viable.

In the context of financial advisors in particular, the rise of technology and the opportunities of cross-subsidy models introduce the potential for numerous disruptions in the coming years. From an RIA custodian that gives away the actual custody services, trading, and execution for free (and gets paid for its technology platform instead), to model management software that makes it feasible to buy index ETFs (or factor-weighted smart beta, or portfolios with SRI tilts) without the need for a mutual fund or ETF itself, and even the possibility that in the future some financial advisors might stop charging for investment management altogether and instead charge fee-for-service financial planning and “give away” the investment management services for free!

Ultimately, the challenge of disruptive cross-subsidy models is that they still require finding someone who is willing to pay for a key component of value, potentially at a cost that is far higher (or at least far different) than what he/she was accustomed to previously. Nonetheless, from Google Maps disrupting Garmin, to Chance the Rapper and other musicians increasingly giving away their music for free (and getting paid for live performances and merchandising instead), the reality is that significant disruption can occur by finding the one most valuable component of a solution… and giving everything else away for “free” to support that core value.

Is it time for the industry supporting financial advisors – and the financial advisor business model itself – to experience such a disruption?

Technology And The Age Of Disruption

With an ever-accelerating pace of technological change, it seems that more and more industries are being disrupted by technology. Or at least, that’s the prediction.

In practice, it’s somewhat messier. While companies like Uber and Airbnb and Amazon in particular have had rapid disruptive impact, other technology innovations – like the “robo-advisor” movement in financial services, which still has less than 1% market share after 6 years – turn out to merely win a small incremental share of the market, rather than disrupt it.

Some of the biggest disruptions, though, come when industries collide, which creates the potential for the economies of one industry to fundamentally disrupt the pricing and business model of the adjacent industry – in some cases, where one competitor literally gives away its solution for free, because the company has “other ways” of making money.

In some cases, this is a classic “loss leader” or “freemium” approach to marketing, dating back to when King Gillette famously gave away razors because he knew people would end out buying a lifetime of razor blade refills anyway – or in the model era, how wireless carriers give away low-cost or entirely free cell phones, that are ultimately subsidized by expensive data plans.

In other situations, though, the model is not one of “loss leaders” – where a disruptive offering is given away for free because it’s expected to be profitable later – but a “cross-subsidy” model, where a solution is free and remains free because there is some other aspect of the business that generates revenue. For instance, radio, television, and most newspapers have historically been “free”, because they were cross-subsidized by the advertisers who were willing to pay the entire cost of the business for the opportunity to get in front of the readers/viewers/listeners (which so institutionalized “free” news that it’s still difficult for even quality organizations to get paid for it today!).

And notably, the cross-subsidy model exists in many industries and domains. Chance the Rapper has managed to become a (financially) successful musician by giving away his music for free, because he makes his money from those who hear the music online and then pay to see him live (a model that more and more musicians are adopting as streaming services reduce the income from selling “records” but boost reach to make concerts more profitable).

Although such disruption is perhaps most commonly seen in the technology industry. Such as when Google disrupted Garmin and other in-vehicle GPS navigation devices, by giving away a (superior) Google Maps product for free... because it was financially supported the rest of Google’s business (advertising) model, forcing Garmin to focus on other markets for GPS devices instead. Woe to the company whose prior product has to compete with the “free” version of a well-cross-subsidized competitor!

In practice, though, cross-subsidy models can be challenging to establish, because someone still has to pay, and it may require at least one group of customers to pay for something they’re not accustomed to paying for (in order for someone else to get it free). Thus, Google Maps couldn’t disrupt Garmin, until it established the validity of online advertising to make (other) companies willing to pay to subsidize Google Maps in the first place.

Nonetheless, the disruptive potential is tremendous. And has long existed in the financial services industry as well. Look no further than RIA custodians who give away “free” custody services to RIAs… not to mention bundled technology, from Fidelity’s full Wealthscape platform to TD Ameritrade’s iRebal software (alongside the whole VEO platform itself), because RIA custodians get paid via business cross-subsidies, from securities lending and order routing to earning a spread or net interest margin on cash.

Which raises the question: what other disruptive possibilities may emerge in the financial advisory industry from here?

Charge For Technology And Give Away RIA Custody For Free?

Arguably, one of the first and best disruptive possibilities is for the RIA custodial business model itself. As while historically, it’s been “great” that RIAs have been able to get RIA custody services “for free” – because of the cross-subsidies that already exist – those current cross-subsidies are becoming increasingly tenuous, opening the door to new models.

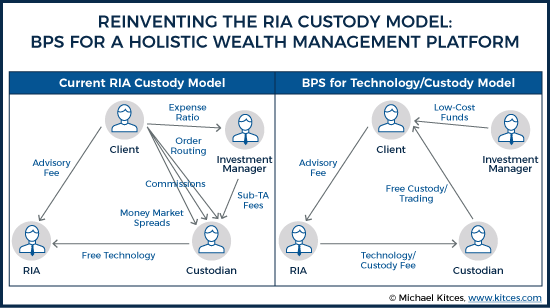

In practice today, the overwhelming majority of RIA custodian revenues come from just a few narrow cross-subsidy buckets – earning a spread on money markets (or net interest margin on cash deposits via an affiliated bank), securities lending and margin lending, trading commissions, order routing, and shareholder servicing and sub-TA fees (or sometimes, other sponsor or shelf space fees) paid by asset managers to be on the custodial platform.

Except the fundamental challenge is that as fiduciaries – and businesses simply trying to demonstrate value to their own clients – RIAs have spent years systematically chipping away at those RIA custodian revenue streams! Focusing on best execution order routing, moving cash balances to higher yielding options (or using emerging new technology services like MaxMyInterest to automate it), discouraging the use of margin, minimizing trading fees, and selecting the lowest cost investment options (which in the case of some are cheapest precisely because their expense ratios don’t include room for custodial payments for shareholder servicing or sub-TA fees), are all things that RIAs do that minimize the cross-subsidies of the current custody model.

And the issue has recently been coming to a head, from controversy around Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolios “robo” service being offered for “free” but requiring a substantial cash allocation (on which Schwab Bank earns a net interest margin), to Fidelity previously raising ticket charges on DFA funds, to TD Ameritrade recently stripping out Vanguard ETFs from its ETF Market Center because Vanguard wouldn’t make any back-end shareholder servicing and sub-TA payments to TD Ameritrade. And the end result of each… RIA adoption of Institutional Intelligent Portfolios has been lackluster, many DFA-based RIAs moved away from Fidelity in recent years, and there was such significant backlash against TD Ameritrade for the removal of Vanguard ETFs that it forced them to extend the transition window.

Ultimately, RIA custodians are entitled to get paid – as with any business – but the “need” to drive the current set of cross-subsidies is increasing tension between RIAs and their custodians, even as the platforms build out more and more technology tools that make it absolutely essential to use an existing custodian to run your business as an RIA anyway. Which means it may only be a matter of time before some RIA custodian tries a new disruption: charge (basis points) for the technology, and just give away all the custody services for free.

As some advisors might note, paying basis points for technology seems very cost-ineffective – especially for larger firms – compared to paying the fixed monthly or annual costs of many software providers today. Yet the reality is that most RIA custodian cross-subsidies are already in basis points, from the spreads on money markets, to the shareholder servicing and sub-TA fees of mutual funds and ETFs.

In essence, most of the RIA custody model already boils down to “getting paid basis points on assets on platform” and measuring the profitability of advisors based on their custodian-revenue/assets ratio. The distinction, however, is that a straight bps-for-custody model reduces many of the other conflicts between RIAs and their custodians, from the pressure to keep cash on platform, to fighting about the cost of ticket charges (which should vanish entirely in a bps-for-custody model), to the ability to get the true lowest cost version of funds (e.g., DFA funds without ticket charges, Vanguard ETFs without shareholder servicing fees, or American Funds F-3 shares).

In fact, in many cases, the clients would end out with approximately the same all-in cost anyway! After all, the whole point of the model would not necessarily be to raise the custodian’s revenue/assets pricing, but just to simplify it, make it more transparent, reduce the inherent conflicts so RIAs and custodians can grow more effectively together, and focus on the real value proposition (the technology) and not the commoditized components (basic custody services).

In reality, this bps-for-custody model exists to some extent already – with the availability of asset-based wrap fees in lieu of trading commissions – but the real opportunity is to expand asset-based wrap fees into a full-platform fee, that allows the custodian to give “everything” away in the custody business (including the trading fees), in exchange for a robust technology layer that the advisor uses to run their business.

Which is actually very close to what tech-savvy Apex Clearing is already trying to do in entering the RIA custodian marketplace, albeit by partnering with “robo” middleware technology players that would blend their fees on top of an asset-based wrap fee to formulate a single platform fee.

Just think of it from the advisor perspective: if you could get all the technology you need, plus have the true lowest cost version of every possible fund and ETF, the highest yielding money market (no custodian spreads!), better assurances of true best execution (no incentives for order routing), and all with no trading costs at all… what would you pay as an all-in-one bps-for-custody fee? And if it added up to the true net revenue/assets cost that you and your clients are paying anyway – which would you prefer?

Indexing 2.0: “Robo” Technology To Disintermediate Pooled Investment Vehicles (Mutual Funds And ETFs)?

While one possibility for technology disruption is that it becomes the primary thing that advisors and clients pay for – with the rest of the custody services thrown in for free – another option is simply that the efficiencies and economies of scale that technology can bring may disrupt some of today’s intermediaries.

For instance, consider the mutual fund (or its more recent brethren, the exchange-traded fund). For most of its existence, one of the primary benefits of a mutual fund was, as a pooled investment vehicle, to gain trading economies of scale that reduce the drag of transaction costs. Especially in their early years, when Wall Street trading costs were both high and fixed, it was crucial to invest a substantial dollar amount at once to mitigate the impact of the ticket charges. Thus, investors didn’t just buy stocks a few shares at a time individually. They invested into mutual funds, which in turn pooled their dollars together to buy hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of shares at a time, because a $200 ticket trade (at the time) didn’t take nearly as much of a bite of a pooled 10,000 share purchase as it did of an individual’s 10 share trade.

However, since the SEC eliminated fixed trading commissions on May Day of 1975, the cost to execute a stock trade has plummeted (by more than 90% in the first 20 years alone), and the need to pool investment dollars to make stock purchases at a “reasonable” price has been less and less relevant. And would actually be made completely irrelevant in a world of asset-based wrap fees (or trading commissions that are bundled into RIA custody)!

Which raises the question of whether a mutual fund or ETF is actually still necessary today?

Of course, with some ultra-low-cost index ETFs from companies like Vanguard, it’s difficult, even with efficient technology tools, to get exposure to the total stock market for as little as 4 basis points. And for actively managed mutual funds, ostensibly there is value not just to the mutual fund as a vehicle to pool investment trades, but the ability to delegate to the mutual fund manager themselves to select the trades… which, in the absence of a mutual fund, falls back to the investor themselves to choose (or to hire another expert).

Nonetheless, in a world where the transaction costs are less and less relevant, the pooled mutual fund is no longer the “only” way for a centralized investment manager to make investment decisions for a distributed group of investors. For instance, many financial advisors already use rebalancing software to manage model portfolios across multiple individual accounts, so each client’s account is invested consistently (but individually).

In addition, we’ve seen the rise of Turnkey Asset Management Platforms (TAMPs), Separately Managed Accounts (SMAs), and more recently the emergence of the Model Marketplace. Of course, many of those still commonly use ETFs (or even mutual funds) as their “building blocks”, instead of individual securities like stocks and bonds. But it seems only a matter of time before ever-improving rebalancing and model management software makes it feasible to manage a wide slate of individual securities, and just eschew the ETF or mutual fund wrapper altogether.

For instance, instead of paying an average of almost 0.50% for a smart beta ETF, imagine simply buying a “robo-advisor” software solution that uses software to manage a model that replicates all of the holdings of a smart beta ETF, but at a robo-advisor software price of “just” 0.25%? In essence, the technology would disintermediate the ETF manager.

In addition, with the advisor implementing their own technology, there would be no particular constraint for using a specific existing smart beta allocation. Instead, an advisor might establish their own parameters, giving their own customized client-specific weightings to small cap, value, momentum, and any other factors they wished to over- or under-weight. In a world where the average price of robo-advisor technology is already cheaper than the average cost of a smart beta ETF!

And the opportunity is not limited to smart beta. Technology tools could similarly disintermediate socially responsible investing funds (for technology-driven solutions that adjust weightings to be perfectly customized to the client’s own SRI preferences). Active managers could be selected directly from an available menu, with trade orders simply routed through technology for implementation in the client’s individual account (a natural extension of today’s SMA and Model Marketplaces).

Even the index fund itself could be threatened. After all, why pay for an S&P 500 index fund, when it’s possible to simply use low-cost technology to own all the individual components of an S&P 500 index fund instead?

Of course, when it comes to true index funds, the current costs are so low – typically in the range of just 3 to 7 bps – that there isn’t much cost left to eliminate with technology. However, the reality is that when the underlying stocks of an index are owned individually, it can be more tax efficient – at least for individual investors in a brokerage account. The reason is that when the individual stocks of the index are owned individually, each can be tax loss harvested individually, in a manner that cannot be done with an index fund.

Example. If at the end of the year, the S&P 500 is up by 7%, because 353 of the stocks were up for the year, and 147 were down, then the S&P 500 index fund investor cannot do any tax loss harvesting (since the index fund itself is up). However, the technology-driven indexing solution could harvest the 147 stocks that were down, while continuing to hold the 353 that were up, producing a natural tailwind in favor of the “Indexing 2.0” solution over the current index mutual fund/ETF approach.

Which means even if the Indexing 2.0 technology solution was slightly more expensive than a traditional index ETF, it may still be less expense on a net after-tax basis (at least for those individuals investing with dollars in taxable accounts) thanks to the added value of more efficient tax loss harvesting that can more than overcome the difference between low-cost technology and a low-cost index ETF!

More generally, though, the fundamental point is simply that as trading costs continue to fall – and perhaps “go to zero” with a bps-for-custody platform that completely eliminates individual ticket charges – the potential emerges for technology to disrupt and displace pooled investment vehicles, including both mutual funds and ETFs, with both “Indexing 2.0” and technology-driven smart beta and other customized-model-driven solutions!

Charge (Retainer) Fees For Financial Planning Advice And Give Away Investment Portfolios For Free?

While technology is often a catalyst that outright makes a new business model and value proposition possible, in practice technology can also “force” new business models and value propositions to emerge, by making “old” models obsolete.

In the context of financial advisors, this phenomenon isn’t actually new at all. In the 1970s and 1980s, a “financial advisor” was a stockbroker, getting paid generously for each stock transaction that was executed. Until the “technology companies” of the era – like Charles Schwab, Ameritrade, and Scottrade – used technology in lieu of the human stockbroker, scaling it to the point that the cost to execute a stock transaction fell by more than 90%, effectively putting the stockbroker out of business and rendering the pure stockbroker model obsolete.

Of course, financial advisors didn’t disappear with the disruptive impact of technology. Instead, they evolved to a new business model and value proposition – identifying and recommending the best mutual funds, which both spawned the explosive growth of mutual funds themselves in the 1990s, and also the rise of the independent broker-dealer (as once financial advisors sold third-party mutual funds instead of first party stocks from dealer inventory, it became possible to be an “independent” under a broker-dealer!). And the business model shifted as well, from getting paid based on the quantity of trades (at a fixed trading fee), to getting paid based on the total amount of assets on which an upfront commission load was paid (plus a small 12b-1 servicing commission trail).

However, eventually technology showed up once again – with the rise of the internet, the emergence of online brokerage firms offering “mutual fund supermarkets”, the availability of online resources to research funds (from Yahoo Finance to BigCharts and Morningstar.com), consumers suddenly began to ask “why pay a load to a financial advisor, when I can buy a no-load version of the mutual fund directly?” Marking the beginning of the end of the mutual fund era for financial advisors.

Although once again, financial advisors didn’t disappear with the disruptive impact of technology. Instead, we once again evolved to a new business model and value proposition – creating asset allocated diversified portfolios (instead of just picking individual mutual funds), and the AUM model (either as an RIA, or via 12b-1 fees or fee-based wrap accounts at a broker-dealer).

Until yet again, technology has arrived – now in the form of TAMPs, SMAs, rebalancing software, model marketplaces, and most recently the “robo-advisor” – that is reducing the value proposition of offering asset allocated portfolios, and driving financial advisors to step up on their value once again… and raising the question of whether a new and different business model may emerge as well?

The most disruptive possibility? What if financial advisors begin to charge for fee-for-service advice, and give away the investment portfolio implementation for free? (Especially since technology makes it feasible to deliver to clients at a near-zero cost anyway?)

For instance, what if an advisory firm that currently charges 1% for asset management and “includes” financial planning for a $1,000,000 client, instead charged $10,000 for financial planning and “included” asset management? Notably, the total cost to the client isn’t necessarily different – 1% of $1,000,000 is $10,000 as well – but the positioning of the value to the client is substantially different!

Clients who “primarily” wanted financial planning, for whom the value of asset management was tenuous, may be far happier to pay for what they want, and get the “lesser value” asset management included.

Of course, clients who still want (active) investment management – and only asset management – would ostensibly still pay an AUM fee for that service. Still, the idea of “giving away” asset management alongside fee-for-service financial planning, in a world where the dominant model is to charge for asset management, creates significant disruptive potential.

How many clients really just want to pay for financial planning in the first place, and “can’t” buy it because they don’t want – or can’t even qualify for – asset management services? What kind of specialized high-value financial planning could be offered by a firm that was fully focused on it as their core value to clients, for which asset management was just incidental and bundled in?

And what other “no-load” product solutions might be offered to clients as well, in an already-bundled financial planning fee? With DoL fiduciary spurring new product innovation, will a financial planner soon be able to offer a wide range of no-load life insurance and annuities as well as no-load investments? How much of what consumers pay for today (typically via commissions) could be entirely “free” in a predominantly fee-for-service financial planning model?

Ultimately, it remains to be seen whether any of these financial advisor industry disruptions will come to pass. Because in the end, services must still be paid for, somehow. And changing business models, in a way that requires services to be paid for in a different manner than they currently are, can be challenging – as someone will be required to pay, or at least visible see a cost, that they are not accustomed to seeing.

Nonetheless, in the end, disruptive cross-subsidy models “work” because they’re successful at charging the people who are most willing to pay for the service they find most valuable and worth paying for.

So to the extent that the value of custody is really the technology and trading, the value of asset management is really the (technology tools to manage) models and asset allocation, and the value of financial advisors is really the financial planning (and not the asset management)… all of these areas may be ripe for disruptive potential!

So what do you think? Would you prefer to have a simpler RIA custody platform with one all-in bps-for-custody payment, that provides access to the lowest-cost version of every mutual fund and ETF with no trading fees? If technology made it easier to manage large portfolios of individual stocks “just like ETFs” but without the ETF wrapper (and cost), would you use it? Could a financial planner really get paid for “just” financial planning, and give away investment management for free? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

Great ideas here! We partner with a local food bank, and for every introduction we receive, feed a local child for a month.

It amazes me how you guys create such insightful content week after week! I keep reading different blogs that I don’t think can get any better and the next week – another one comes out full of highly valuable information on a completely different topic… All the information on Kitces.com saves me a HUGE amount of time, a lot of blunders and provides great guidance. You really are living your mission of advancing knowledge in financial planning and I want to make sure you know this is very much appreciated by people on the other side of the world! With grateful thanks, Sam

Thanks Sam! Happy to be of service! 🙂

– Michael

> an advisor might establish their own parameters, giving their own customized client-specific weightings to small cap, value, momentum, and any other factors they wished to over- or under-weight.

Yes! This is a great use case of our personalized portfolios solution. To control weightings to smart beta, ESG, or any other asset class/sub asset class on a per client basis. To learn more, visit us at http://www.capitect.com.

Totally agree. Value of financial planning is in strategic advice which clients really want, not in isolated asset management.

I have already needed to start doing this for many of my clients. While my goal is to grow AUM, my niche has many clients whose primary investment account is their USG TSP account. They don’t yet have enough in non-TSP assets to qualify as an AUM client. However, they still need and want financial planning. I do comprehensive planning and recommend a self-maintaining portfolio like Vanguard’s LifeStrategy Funds for these clients. I completed about 85 comprehensive plans in the past 12 months following this model.

This requires a lot of ‘selling’ on my part, but it has given me incredible planning experience. Having completed hundreds of plans in a somewhat short time provides better quality planning for my clients because it allows me to be a real expert for this niche. My plans are not cookie cutter and each one is developed collaborative with each client. I even help with implementation when needed.

The biggest issue with the move to the retainer model is that you can’t deduct the full amount from retirement accounts. Let me know if you figure out away around this. And I know technically you shouldn’t be able to deduct the 1% management fee, but I am pretty sure this is industry standard. Could be wrong.

Are we helping clients do financial/investment transactions (now mostly lowest-cost automated) OR are we helping them secure their financial health, invest their assets wisely and retire well?

As a RIA, I know the “nakedness” of getting paid for “just” financial planning instead of hidden investment management fees/margins/commissions scares the crap out of me. However, it delights my clients. Without them I have no business. So the course is clear.

PS. the latest Tax Reform Bill for the 1% will be great for my business as it will muddy the waters with lots of new tax schemes, money movement and associated asset management opportunities – in other words more “hidden” fees. This will delay the need to strip naked and serve my clients honestly.

I think the industry will move towards a split revenue model. Planning will be offered via Retainer, Hourly & Project Based fees while Investment Management services will be offered at a lower cost compared to today.

Maybe it’s just my personal preference for my future non existent solo firm, but I can see a scenario where you charge a $3500ish annual planning retainer fee with an optional investment management fee of 0.35ish%. The client can decide if they want to implement the IPS on their own or let the advisor manage it.