Executive Summary

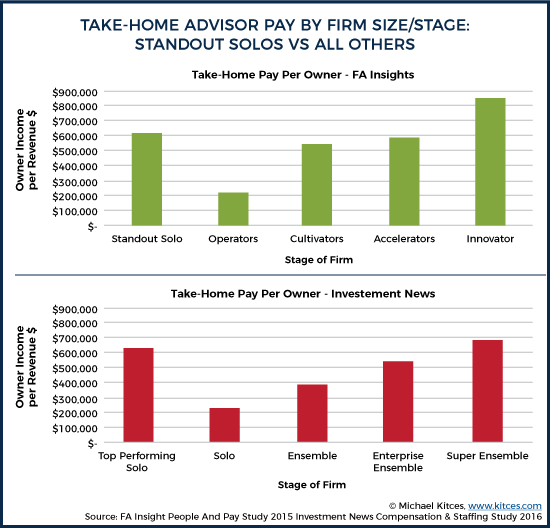

One of the most popular debates in the advisory industry today is whether small advisory firms of the future will be able to compete against the ongoing growth of today’s mega-advisory firms, from the small subset of the largest independent RIAs that control the marketplace (with more than 60% of client AUM held by fewer than 4% of firms), to the national brands like Vanguard and Schwab that are increasingly competing with independent advisory firms directly. Yet despite the negative forecasts, industry benchmarking studies continue to show record profits for the most successful solo advisory firms, generating as much income as the per-partner take-home pay of billion-dollar firms!

The ongoing success of the small firm shouldn’t be such a surprise, though, given the “long tail” phenomenon that is increasingly being observed in many industries – where niche providers can survive and thrive as technology makes it increasingly feasible for consumers to find their way to them, from niche books being found on Amazon, niche music being found via streaming music services, and niche financial advisors able to be found via a simple Google search.

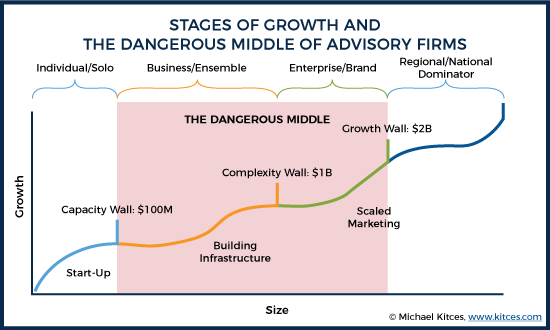

The caveat, however, is that, as the biggest advisory firms scale their operations and marketing and establish recognized brands, while niche advisory firms thrive in the online marketplace of the internet, “something” has to give. But the "something" appears not to be large firms dominating small ones, or small firms picking off the clients of large ones… but instead, both applying substantial business pressure to the dangerous middle in between. Which today would encompass a wide range of advisory firms from $100M to more than $2B of assets under management.

Because unfortunately, it’s the firms in the dangerous middle that are both too small to be big (lacking the scalable marketing and established brands of regionally and nationally dominant firms), but are too big to be small (struggling to capitalize on a focused niche to differentiate). And instead have to grow through a series of challenging business hurdles, from a capacity wall of client service to a complexity wall of operational infrastructure and a growth wall of centralized, scalable marketing.

Fortunately, the good news is that some firms really do grow successfully through the dangerous middle, but the rising pace of advisory firm mergers and acquisitions – with an average deal size directly in the middle of the dangerous middle range – suggests that more and more firms are feeling the pressure to either get much bigger to get past the dangerous middle, or consider how to downsize and get smaller instead (either by outright downsizing the firm, or by tucking into a larger one to simplify the practice).

The bottom line, though, is just to understand that, as the long tail grows longer and the big head grows bigger, the future of financial planning isn’t about whether the “small” firms will win or the “big” firms will win. There is room for both to succeed, as the biggest advisory firms grow bigger with their size and scale and the smallest advisory firms grow more profitable. Just be wary about getting caught in the dangerous middle.

The Long Tail (Of Financial Advisory Firms)

The concept of the “long tail” was first popularized by Chris Anderson in an article by the same name in Wired magazine in 2004, which in turn was expanded into a book a few years later.

The concept of the “long tail” was first popularized by Chris Anderson in an article by the same name in Wired magazine in 2004, which in turn was expanded into a book a few years later.

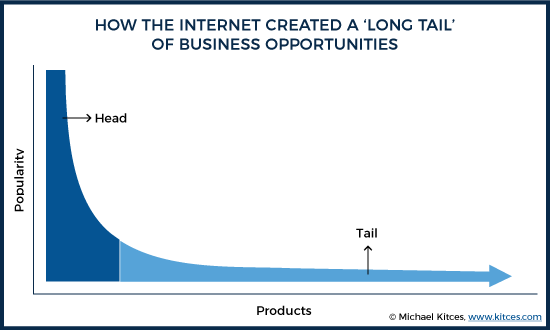

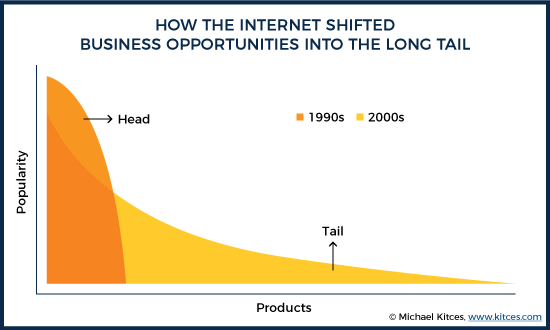

The essence of the “long tail” concept was that instead of trying to find the next hot product to stock in inventory and sell – the traditional challenge of the bricks-and-mortar store in an age where the breadth of available inventory was constrained by physical space and logistics – digital businesses with a near-zero marginal cost to expand their inventory could make a substantial profit in the “long tail” of niche items that individually sold too few units to be economically viable in a traditional store but could be profitable in the online world.

Thus for instance, Anderson’s article noted that, while bricks-and-mortar music stores at the time might only hold 40,000 tracks’ worth of music for customers to buy, Rhapsody (a popular digital music service of the time) was seeing regular downloads of its top 400,000 tracks (which means it was generating a substantial volume of sales amongst 360,000 tracks that traditional music stores couldn’t afford to make available for sale in the first place). Similarly, Barnes & Nobles physical bookstores at the time carried an average of 130,000 titles, but Amazon (back when it was still primarily a book-seller!) generated more than 50% of its revenue outside its top 130,000 titles. And the typical Blockbuster video rental store carried 3,000 titles, but Netflix was generating 20% of its rentals from outside the top 3,000 (and the demand continued to shift further into the long tail as Netflix grew).

The success of this phenomenon has come to be known over time as the development of a “platform” business, where the platform can outcompete traditional businesses by focusing not on the traditional stocking and selling of goods, but creating a marketplace where buyers and sellers can come together in a manner that dwarfs traditional competitors. Thus, as Tom Goodwin recently noted: “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.”

The success of this phenomenon has come to be known over time as the development of a “platform” business, where the platform can outcompete traditional businesses by focusing not on the traditional stocking and selling of goods, but creating a marketplace where buyers and sellers can come together in a manner that dwarfs traditional competitors. Thus, as Tom Goodwin recently noted: “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening.”

However, while the rise of the platform has been a huge success for the businesses that created them, from Uber to Facebook to Airbnb and eBay and Amazon, they’re also an enabler of success for the small niche players themselves, who may have never been able to create an economically viable business on their own, but are able to do so with the help of the technology to give them an efficient way to distribute their products or services.

The Big Head Vs. The Long Tail

The increasingly competitive financial advisor landscape over the past two decades, enabled in no small part by technology itself, has stoked a raging debate about whether the future of the financial advisor business will be focused primarily in the largest of firms that can leverage all this technology to out-scale the average independent advisor… or whether independent advisory firms will be able to leverage technology and the emergence of platform marketplaces to survive and thrive.

Thus far, the answer appears to be “both.”

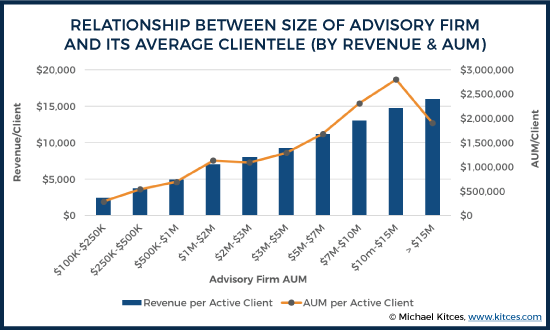

On the one hand, data by Cerulli indicates that there are only 687 RIAs with at least $1B of assets under management (out of nearly 18,000 SEC-registered investment advisers, and even more state-registered investment advisers), but that 3.8% of RIAs now have a whopping 60% of all RIA assets (up from 2.8% of firms in 2012). In other words, the largest firms are quickly becoming the dominant collectors of client assets, using their size and scale to grow even larger and capture more market share, and in turn, attracting the most affluent client who seems to gravitate to the largest firms. Simply put, the big are getting bigger. The race to be a $1B firm in the 2000s is now a race to hit $10B in the 2010s.

Yet on the other hand, industry benchmarking data also shows that the most successful solo advisors are seeing record profits as well, with average take-home pay of more than $600,000/year, and a whopping 75% profit margin (before owner’s compensation). Leveraging the power of the internet – the ultimate discovery vehicle for niche financial advisors – the data shows that advisory firms have to grow above $1B of AUM just to return to the average take-home pay per partner of the most successful solo advisory firms that stay small!

In other words, the issue is not that the largest advisory firms are necessarily beating out the ability of the small firms to compete (which are instead enjoying record profits), nor are the small firms drawing away a material number of clients from the largest firms (which instead seem to be successfully moving further upmarket as they grow).

Obviously, though, something has to give. And what appears to be “giving” are not the big firms losing to the small, or the small firms losing to the big… but the firms that are stuck in the middle.

The Rise Of The Declining Dangerous Middle

The significance of the long tail phenomenon when it first emerged was that it enabled small businesses (those that created niche products and services) to survive and thrive by selling those goods and services in the long tail – naturally drawing away market share from the most dominant companies at the top. The big head of the distribution got smaller as the long tail got longer, and small niche providers who might not have access to customers before suddenly gained access to them (often thanks to the platform itself).

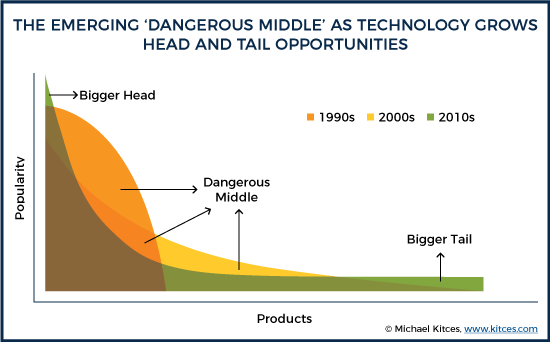

However, online platforms have evolved substantially since the early days of Anderson’s observation of the rising “long tail” phenomenon. As marketplaces grew, suddenly the challenge was figuring out how to select from an overwhelming level of choice, which led to new tools and systems (e.g., ratings and reviews, recommendations from others based on what you said you liked, etc.) that would help consumers discover new products and services of interest, based on what others thought and consumed.

The end result was the rise of products and services that “went viral” – where the social sharing phenomenon caused even more people to buy the most popular products and services, in addition to discovering more niche solutions. Thus, while the long tail grew longer… the head grew bigger, too. And the middle started to get squeezed.

Notably, this shift shouldn’t be entirely surprising, as it’s simply the discovery value of the long tail platform continuing to play out. First, it shrunk the middle by providing a way for consumers to buy products and services in the tail. Then as the platforms and their discovery capabilities grew – facilitating the natural tendency for humans to move in herds – the middle shrunk even further as both the most popular and the most niche benefitted (to the detriment of those remaining in the dangerous middle).

The Dangerous Middle In Financial Advisory Firms

When it comes to being a financial advisor, the dangerous middle is quickly evident in the decline in advisor take-home pay as advisors grow materially beyond $100M of AUM and begin down the path towards $1B of AUM. Which is even harsher given the reality that it can take a decade or often an entire career just to complete that growth path!

The reason is that advisory firms tend to hit a number of consistent challenge points as they grow down this path. The first is a Capacity wall; given that, as human beings, most financial advisors simply can’t mentally handle more than about 100 client relationships. Which means the advisory firm has to bring on additional advisors (or outright additional partners), increasing the overhead costs of the firm and/or splitting its net profits, and reducing per-advisor take-home pay.

Once the firm grows past its capacity wall, it has to begin building infrastructure to handle operating as a multi-advisor firm, until eventually, it hits a size and complexity wall, beyond which the firm has to reinvest even further into staff, systems, and technology. This is the stage where the firm hires a Chief Operating Officer, revamps its various software tools from CRM to trading and rebalancing, and incurs a series of additional infrastructure costs in an effort to grow and scale further.

And even if the firm makes it through the infrastructure-building phase and clears the complexity wall, the advisory firm then hits a growth wall, where the individual efforts of the founders to bring in new clients are no longer sufficient to power the growth of an ever-larger enterprise. Which in turn forces the advisory firm to then figure out how to establish and formalize a brand for itself, systematizing and scaling its marketing to power the growth of the firm to the next stage of actually becoming a regionally or nationally dominant firm.

The caveat, of course, is that many firms will never make it over the complexity and growth walls of the dangerous middle.

In practice, this “dangerous middle” for modern advisory firms today appears to start at the point firms reach “multi-advisor” status (typically around $50M to $100M of AUM), and likely doesn’t end until the firm is $2B+ of AUM (or higher) and has managed to clear its growth wall by systematizing its marketing with a standardized company brand (beyond which, growth rates typically start to tick up again).

The significance of this admittedly wide range of the “dangerous middle” is that, as noted earlier, many/most advisory firm founders may spend a lifetime trying to grow from $200M to $2B (a 10X growth cycle that takes 17 years even with a healthy 15%/year growth rate, and that’s after the difficult journey just getting to $200M of AUM in the first place!).

In this context, it is perhaps no great surprise that there continues to be a steady pace of advisory firm mergers and acquisitions, almost all of which are occurring precisely in this “dangerous middle” range, with the average transaction hovering right around where most advisory firms hit the complexity wall (approximately $1B of AUM). In essence, more and more firms in the dangerous middle are either deciding to merge together and try to achieve the scale necessary to become a market dominator, to sell and let a larger firm use the acquisition to power their path to scale, to tuck in and let someone else deal with the business challenges so the advisor can re-focus their energy on what they enjoy most (serving clients), or instead to simply downsize their practices and revert to a smaller-but-more-profitable long tail firm instead.

Fortunately, the good news is that some advisory firms do manage to grow their way through the dangerous middle, though admittedly as the largest firms leverage their scaled marketing to get even larger (now including national brands now competing with independent advisors like Vanguard and Schwab), growing through the dangerous middle is harder than ever.

The bottom line, though, is just to understand that, as the long tail grows longer and the big head grows bigger, the future of financial planning isn’t about whether the “small” firms will win or the “big” firms will win. There is room for both, as the biggest advisory firms grow bigger with their size and scale and the smallest advisory firms grow more profitable (leveraging the ultimate marketplace for niches: the internet), each providing different services as they compete for various segments of the consumer marketplace. Which means the choice isn’t about whether to be big or small in order to succeed; both can succeed. Just be wary about getting caught in the dangerous middle.

So what do you think? How can mid-sized firms work through the dangerous middle? Can smaller and start-up firms continue to serve increasingly specialized niches? Will new solutions emerge to help firms scale faster and easier? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

I am resurrecting this Dangerous Middle to say the “lifetime” effort is dangerous because owners are unconsciously allowing their firms to bloat by keeping not-fit staff and clients. This bloating drags down compensation, culture, quality of service, and business development. As the owner begins to burn out from the effects of bloating, they reach for solutions like shiny objects, random marketing, cutting random expenses, and on boarding advisors with clients in hopes of getting out of this dangerous middle. And they start to hallucinate and think a billion+ revenue is the Holy Grail and the moment they can hire someone else (aka. COO) to fix the bloating, restore comp and quality service, and pull them from the abyss of burnout. I say the middle could be the Holy Grail if leaders are willing to re-calibrate. I see this happening slowly but more often each year. These leaders are not allowing bloat, lowered comp, energy sapping cultures and degrading service. They are embracing the emotional upheaval of the middle, re-calibrating clients and staff, and celebrating well before the billion+ mark. They are leaning in, daring to lead, breathing as often as possible, and realizing that the middle can be a wonderful, not dangerous, place.