Executive Summary

In a world where most major purchases – such as buying a house or a car – cannot be done with cash, the practical constraint to the question “how much can I afford to buy?” is usually based on “what monthly debt payment can I afford to make?” As a result, lender thresholds for the maximum amount to borrow – such as the popular 28/36 debt-to-income-ratios – are typically used to determine affordability.

However, the reality is that what’s good for the lender may not necessarily be good for the borrower. After all, lenders lend money assuming that at least some people will default, and that the rest will do ‘whatever it takes’ to repay the loan, even if that means significantly curtailing lifestyle. In other words, lending guidelines are based not on fiscal prudence, but the maximum amount of pain the borrower is anticipated to tolerate without causing mass defaults!

In turn, this suggests that when evaluating how much a borrower can really “afford”, without potentially making themselves miserable, lender guidelines should not be relied upon. Or at least, it suggests that consumers need a #FinTech tool for themselves, that can evaluate the financial risk of their borrowing, but based on prudent borrowing that minimizes the risk of default, rather than maximizing the level of “acceptable” default loss for the lender!

Of course, ideally the determination of spending levels shouldn’t be based on what you can afford (by borrowing against the future!) in the first place, but what is “enough” to bring about a comfortable lifestyle. Though in a world of trying to “keep up with the Joneses”, that is clearly easier said than done!

Debt-To-Income (DTI) Mortgage Lending Limits

Whether it’s buying a house or a car, one of the most common questions asked for any large purchase is “how much can I borrow?” After all, very few of us can afford to make such a major purchase with 100% cash. Realistically, most big transactions involve borrowing money in a lump sum to buy, and then repaying it over time via monthly payments. Which means figuring out “how much can I buy” is ultimately dictated by “how much can I [afford to] borrow?”

In turn, lenders decide how much to lend to a prospective buyer based on what that monthly cash flow obligation will be, and how it relates to the borrower’s income, by calculating the borrower’s debt-to-income (DTI) ratio.

In the case of housing, lenders typically include a debt-to-income limitation that monthly housing payments (including principal, interest, taxes, and insurance, or PITI) should be no more than 28% of monthly gross income (a debt-to-income ratio commonly known as the “housing ratio” or “front-end ratio”). In addition, a borrower’s total monthly payments for all obligations – including PITI mortgage payments, along with credit card payments, child support (and sometimes alimony), and other loan obligations (e.g., car payments) shouldn’t exceed 36% of monthly gross income.

These thresholds may be further impacted by those who are ‘especially qualified’ to borrow, such as buyers who are making a larger downpayment, have greater emergency savings, and/or have an especially good credit score. Given some of these factors, the FHA will allow the back-end ratio to go as high as 43% (and the housing ratio to be 31%), even with (just) a 3.5% downpayment. And certain types of Fannie Mae loans will permit the back-end ratio to go as high as 45% (or even 50% with other mitigating factors).

A similar framework occurs with auto loans, for those who already have a mortgage (and/or are renting), where again lenders will typically finance an automobile purchase up to a back-end ratio of 36%. Ironically, this means that buyers who didn’t already “max out” their debt-to-income ratio when buying a house, will often do so by purchasing an automobile up to the loan limits thereafter!

How DTI Limits Mask Remaining Lifestyle Affordability

Notwithstanding the fact that debt-to-income limits are so widespread – to the point that many people use them to figure out how much house or car they can afford – DTI thresholds are actually a remarkably poor financial planning measure to determine affordability.

First and foremost, the reason is simply that income ratios can tell a very different story in actual dollar terms.

Someone who makes $50,000/year and pays 36% in debt payments (and 15% in income/payroll taxes) will only net about $2,000/month for all other expenses, including food, clothing, and everything else needed to maintain a lifestyle. On the other hand, a self-employed couple that makes $150,000/year at the same 36% debt limit (and now potentially paying 30%+ in income and payroll taxes) will still have about $4,000/month for all other expenses. And a couple making $250,000/year with 36% in debt payments and 35% in cumulative tax rate obligations will have $6,000/month leftover for food, clothing, and the rest.

Of course, the amount of house and car that can fit within that 36% debt payment will be very different between the $50,000, $150,000, and $250,000/year income levels. Yet the difference in actual hard-dollar cash flows available for all other types of expenses, after debt and tax payments, is also quite material. Depending on the geographic region and its local cost of living, the $50,000/year individual might struggle to live a moderate lifestyle (e.g., San Francisco or New York City), while in other parts of the country the remaining income would be more than enough.

The fundamental point – evaluating debt based on income ratios alone may obscure whether the remaining assets and income are sufficient to maintain the desired lifestyle in actual dollar terms.

Why DTI Limits Are A Bad Measure Of Affordability

The primary reason why debt-to-income thresholds are a bad measure of affordability, though, becomes clear once you consider why they exist in the first place: they’re a measure used by lenders to determine the maximum amount of debt someone can possibly handle.

In other words, lenders don’t set DTI limits based on what would be considered “prudent” or “reasonable” spending for a given level of income. The thresholds are set at what lenders believe is the maximal amount of financial duress a household can take on while still, ultimately, eventually (but perhaps just barely) managing to pay the money back. It’s the maximum amount of risk the lender is willing to take in pushing the borrower to the limits of repayment.

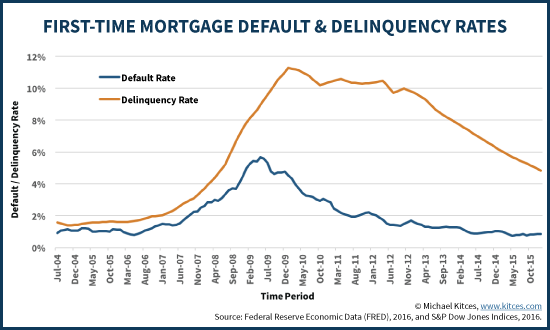

And in fact, lenders recognize that even at current debt-to-income guidelines, some borrowers are likely to fall behind (become delinquent), and a few will likely still default (be unable to repay at all). Not surprisingly, those delinquency and default rates will fluctuate over time, driven in large part by the business cycle and unemployment levels, and spiking whenever a recession occurs. But even in “good” times, there are still borrowers who fall behind on their payments, or default altogether.

In other words, even during good times, lenders assume and recognize there will be defaults. And they further adjust borrowing rates based on the reality that delinquency and default rates can go higher in times of economic stress. Which means ultimately, lending limits and borrowing rates are once again based not on "what's prudent" and "safe", but on what represents an "acceptable default loss" knowing that the borrowing is already so high that some people won't be able to repay.

Accordingly, lenders will sometimes allow higher debt-to-income ratios amongst households who make larger downpayments, because at higher debt-to-income levels it’s even more likely that someone will fail to repay the debt… but at least there’s still a good likelihood that the underlying asset (e.g., the house, or the car) will have sufficient value to avoid any loss for the lender. Not that it's better or more prudent to borrow more at higher income levels or with a larger downpayment, but simply because the lender can foreclose as a last resort, take possession of the property, and sell it themselves to repay the debt and minimize any of the lender's financial loss. For the borrower, of course, that’s still a disastrous outcome.

Nonetheless, the fundamental point remains: lender set debt-to-income thresholds assuming it’s so unaffordable that at least some borrowers will default, and the rest will eventually manage to repay, albeit with some potential struggle. After all, if you’re a lender in the business of lending money, you want to lend as much as you possibly can get anyone to borrow… as long as you can still ultimately be (mostly) repaid. Whether that makes the borrower miserable in the process literally isn’t part of the equation.

How SHOULD You Figure Out A Prudent Borrowing Amount?

So given that lender guidelines are based on tolerable maximum risk for the lender – which is past the point of basic prudence for the consumer, given that lenders assume there will be some delinquencies and defaults – what is the appropriate guideline on debt-to-income thresholds and “reasonable” borrowing?

The first target could simply be: something less than what the lender is willing to lend as a maximum. If the lender uses the thresholds of 28/36 on front-end and back-end ratios, choose something lower. It could be 3% lower. Or 5% lower. Anything would be an improvement. Because again, those borrowing limits are based on the maximum pain the lender believes the borrower can tolerate and still (usually) repay; that should not be a “goal” for the borrower!

Ultimately, though, ‘prudent’ use of debt is almost certainly more nuanced. As noted earlier, debt-to-income ratios say very little about the actual dollar amounts left over remaining to support the essentials and one’s overall lifestyle. And depending on where you live, and the lifestyle to which you’re accustomed, those remaining dollars could be more than enough, or grossly insufficient.

Ironically, perhaps the best approach to determining prudent borrowing would actually be to look at it like an underwriter who evaluates the risk of lending money in the first place, looking in depth at cash flow commitments and available resources. Except the debt target would not be based on an “acceptable loss” of delinquencies or defaults, but a threshold low enough to virtually eliminate them.

In this context, one could imagine a #FinTech software solution where the consumer determines how much is “safe” to borrow by looking at similar factors to what applies in mortgage and automobile loan underwriting now – such as debt-to-income ratios and available savings – but also go one step further, looking at your actual lifestyle spending as well, and how flexible it is. (After all, the lender doesn’t care if your mortgage crimps your lifestyle, but as the borrower you probably do!) Other factors might include whether you’re properly insured against potential risks (e.g., health insurance, auto insurance, disability insurance?), and how stable your job and income streams really are.

Of course, the reality is that many of these factors are considered when applying for a mortgage or automobile loan already. Still, though, the lender views it from the perspective of lending the maximum amount of money to make the maximum amount of income while targeting maximum permissible level of default. Which is fundamentally different than a borrower who might be aiming for a prudent amount of borrowing that uses a prudent amount of income while minimizing the risk of default. Not to mention the fact that debt borrowing which constrains the borrower can be limiting in other ways – for instance, the individual who has an opportunity to go back to school or take a new job or launch a new business… but can’t, because the committed debt payments have them locked into their current job to be able to afford to make the current mortgage and car payments.

In the end, though, perhaps the real point is simply to acknowledge that figuring out how much money to spend based on the maximum level of borrowing (“prudent” or default-based) is simply a bad approach to begin with. Instead, the ideal would be getting comfortable with a lifestyle that allows you to do the things you enjoy, without looking at debt as an opportunity to forever creep that lifestyle higher by borrowing against the future, especially given the research finding that buying “things” doesn’t appear to improve our long-term happiness anyway. But the question of how much spending is “enough” for happiness, and how to step off the hedonic treadmill altogether, is a conversation for another day!

So what do you think? How do you determine what is a "prudent" amount of money to borrow? Do you rely on lender debt-to-income guidelines for borrowing affordability?

Amen. I have been saying this for years to my clients. And, I myself never had home debt that I could not pay off over a 5 year period. It is so important to not buy too big a home and be house rich and cash poor. The real estate agents will always try to push you to higher price points (and the homes always look much better). Pick a price to suit your budget and stand firm.

Too many young adults are getting out of school (with debt)and wanting to buy a home right away as though it is a right of passage. Always better to rent when moving to a new area for a few years to get the lay of the land anyway.

Many of my Baby Boomer clients are now downsizing and feeling much freer.

I am a believer in minimal debt and appreciate this article. I will say, to your first sentence (“In a world where most major purchases – such as buying a house or a car – cannot be done with cash…”), buying a car CAN definitely be done with cash. In this keeping up with the Jonses world, however, many people choose not to do it and buy more than they can really afford. Great article!

I completely agree with Lucy. There is usually no good reason why a person needs to finance or lease an automobile if they learn to plan ahead.

In a nutshell, they need to get ahead of the curve by starting off by purchasing an old but safe, reliable car for a few thousand bucks. That might mean driving a clunker for a while, as they save the money they would have been making in car payments and put it in a savings account, which will be used towards a future cash auto purchase. Once a certain level is reached in the car savings account, they upgrade cars and buy a better car with the cash in the savings account. But they still continue to save towards their next car purchase with what they would have been making as a financing payment. And so the process continues until they have the car they desire, fully paid for in cash! They continue with this strategy for as long as they plan to buy cars.

Dave Ramsey (www.daveramsey.com), who specializes in consumer debt, has utilized this strategy with thousands of his radio and audience listeners. Sure, a sacrifice must be made upfront (heaven forbid!), but once that has been done and the savings system is firmly in place, the client never have to drive another clunker again, and never make another car payment again.

Michael,

I agree any prudent investor would follow your advice and discount the debt-to-income guidelines for borrowing affordability (how much to discount, I’m not sure). But the big assumption in those “How Much House Can I Afford” calculators or the #Fintech product you conceive is that potential home-owners’ current income and spending constraints are reasonably indicative estimates of their expected future income and spending constraints.

Banks might reasonably (for their purposes) assume that any couple with the aptitude and work ethic to bring in >150K per year on average have the means to make their mortgage payments each month.

But current income says nothing about a family’s expected future income based on their beliefs and desires (taking into account aspirations to build a business, be a stay-at-home mother, go back to school, etc.), and those beliefs and desires are constantly changing and highly uncertain!

Consider, for example, a couple of DINKS (double income, no kids) who one day aspire on cutting back time from work (no clue when or how much the mother will cut back, so expected future income is uncertain) to have children (no clue how many, so expected future spending is uncertain). Assuming one income and discounting the bank guidelines by 5% seems overly conservative of what the couple can reasonably afford (and sure, they’d like the nicest house they can afford), but adding the two incomes together would certainly constrain the borrowers’ options in other ways which your post nicely highlights.

Do you think a #Fintech product (like, for example FIRECalc for retirement savings) can take such uncertainty into account?

To answer that question, I pose the following to you: how might holistic financial planner approach the open-ended and evolving nature of this couple’s quandry? I am a programmer, and seek to derive a rough algorithm from your planning process. What “data” would you need from the couple, and how might you use it to come up with a number (or more likely, a range).

Sincerely,

Craig

Excellent article, Michael. I recommend that my clients track their spending through Quicken, Mint or similar. This makes it much easier to answer the “how much can I afford” decision by showing how much money is really leftover.

Interesting premise and analysis! Debt is somewhat of a financial PED (performance enhancing drug). Those not using it are at a competitive disadvantage (at least short term) compared to those who are. Ultimately, debt permits consumption smoothing by accelerating future net spending into the present. A Fintech approach might weight the types of consumption prudent to accelerate into the present. Further, re-engineering the lender risk models for consumers to provide a sort of dashboard is possible with adequate variables (liquid assets, household income; # of income sources by type, amount, relative stability; area median income; type of debt – house, education, auto, consumption; and risk reduction tools in place (insurance: DI, life, health, etc). Incurring debt always carries risk and the optimal borrowing opportunities are when one really doesn’t need to.