Executive Summary

As digital software solutions become more sophisticated (and new ones continue to roll out at breakneck speed), they may offer relief with what they offer but, at the same time, they may also introduce a burden for the user to vet and review the results to ensure that it actually provides the 'correct' output. When it comes to digital estate planning solutions tools, this particular burden is amplified not only because of the many clients who need an estate plan (with about 2/3 of Americans estimated to be without a will!), but also because advisors may be concerned that choosing the wrong estate planning solution could create a risk involving legal action, engagement in the unauthorized practice of law, and user error. That being said, advisors who understand how to review and use these tools well can leverage their features and provide considerable value to their clients.

As a starting point, it is important to know what digital estate planning solutions can actually do. Platforms generally help users in the following 3 areas: document creation (creating basic documents such as revocable trusts, powers of attorney, healthcare directives, and wills), document extraction (providing easy-to-read summaries of existing estate planning documents), and estate visualization (creating visual reports that detail the estate plan in a user-friendly matter). Today, services in each of these areas can be provided to users of software technology – without ever having to sit down with an attorney face-to-face.

For some advisors, implementing digital tools as part of their estate planning process can be daunting because they lack the reassuring expertise an actual attorney can provide. Furthermore, a stigma is sometimes associated with 'boilerplate' language or generic document templates. However, in most instances, advisors can help clients realize that boilerplate language can be legally valid, enforceable, and sometimes even preferable (and in many instances, estate planning attorneys themselves often use boilerplate documents anyway!). Accordingly, a digital solution can offer an alternative to the typical process of creating documents after physically meeting with an attorney. Certainly, in more complex situations – such as with ultra-high-net-worth clients, families with unique relationship dynamics, or disabled beneficiaries who need to preserve access to government benefits – an attorney may be required to draft customized estate planning documents or, at the very least, carefully review estate documents created by digital planning solutions. But for the vast majority of 'typical' clients, a digital solution could satisfy a client’s estate planning needs.

One particular concern for financial advisors involved in their clients' estate planning needs is unintentionally engaging in the Unauthorized Practice of Law (UPL) by actually giving estate planning legal advice. While this can create particular liability issues for advisors, digital estate planning solutions can help advisors avoid UPL by providing guardrails that safeguard them from doing so, and by helping them frame their conversations with clients as education and guidance about the options available to them. For example, an advisor may be prompted by the software tool to tell their client: "It may be beneficial to look into whether a spousal lifetime access trust could make sense for you. Here's what it is…". This helps the advisor remain removed from implementing strategies and not risk crossing the line into UPL, but still being able to monitor the client to make sure that things get done.

Ultimately, the key point is that digital estate planning solutions can provide powerful tools that complement the roles both estate attorneys and advisors play for clients, especially for (the many) clients with less complex estate planning needs. With the help of software tools, advisors may find that initiating conversations and offering guidance around estate planning strategies for clients can be carried out much more efficiently and even add to the value they're already providing!

In 1965, Norman Dacey shook the estate planning world when he published "How to Avoid Probate!", which included a strongly worded critique of the probate court system and its associated costs. It suggested that a revocable trust could be a cure for many of the issues caused by probate and provided forms for trusts and wills, along with instructions to implement them.

It was a bestseller with over 2 million copies sold. But Norman Dacey was not a licensed attorney, and his promotion of revocable trusts as an alternative to probate upset the apple cart (to say the least). It required many attorneys who had become comfortable in their probate practices to adjust to this non-attorney's new take on how things could work – and in ways that potentially challenged the fees they could charge to their own clients.

Here is an excerpt from an attorney's published book review at the time:

Probate has a purpose. It gives creditors the opportunity to collect their debts. Heirs are assured of receiving their rightful legacy. The estate assets are protected from improper use of investment. Dacey's trusts will not eliminate all or even most of the necessary costs involved in the post-death administration of an estate. Taxes must still be computed and paid, disputes must be resolved, creditors must be paid, titles must be cleared, and assets must be traced. These "probate-type expenses" will not be erased by merely drafting a trust document.

Certainly, the above insight would not be a common response to the suggestion of avoiding probate in current times. Today, avoiding probate is a key objective of many estate plans.

However, despite his potentially helpful insights, Mr. Dacey was subject to legal actions for the unauthorized practice of law and to stop the future publication and distribution of his book. Ultimately, the legal results were mixed for Mr. Dacey, but his case represented a great allegory to the changes in the realm of estate planning today – namely, the ongoing technological estate planning revolution.

Society is becoming increasingly reliant on digital solutions, and software has become more sophisticated, with new financial planning tools rolling out at breakneck speed. However, many financial advisors have felt lingering resistance and skepticism about the growing use of digital estate planning tools. Everything from compliance/legal concerns to the unauthorized practice of law, user error, lack of specificity and sophistication, and alienating attorney COIs have contributed to the hesitance to adopt these tools.

Digital estate planning platforms are well aware of this list of concerns and have sought to create innovative solutions and guardrails to alleviate them. Accordingly, as new solutions emerge and innovate estate planning, considering these tools with fresh eyes can help advisors set aside their learned fears and understand what these solutions can offer for their clients and their practice.

Only about 1/3 of Americans are estimated to even have a will. The supply and demand issue of estate planning attorneys creating estate plans for clients has not helped this issue. Factors such as an increasing elderly baby boomer population, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the upcoming sunset of the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act in 2026 have contributed to a higher need for estate planning services that estate planning attorneys may not be able to fulfill on their own.

Clients need somewhere to turn for their estate planning needs, especially in an increasingly digital society. A 2022 study by Spectrum Group showed that 93% of clients expect estate planning services from their advisor, yet only 22% actually receive them. Estate planning is a core tenet of financial planning. The Certified Financial Planner (CFP) certification and Certified Private Wealth Advisor (CPWA) designation include estate planning as key components of their curriculum, underscoring the importance of financial advisors being capable of and active in providing estate planning services to clients.

But what does providing estate planning services actually mean? Certainly, advisors usually are not lawyers themselves and, therefore, shouldn't be the ones to provide estate planning recommendations or draft documents. Doing so could be viewed as an unauthorized practice of law. However, that doesn't mean there aren't ways for advisors to still play an integral role in helping to address clients' estate planning concerns.

In fact, advisors are pivotal in helping clients identify and articulate their estate planning needs and guiding them to the best options to implement an effective plan that accomplishes their objectives. That option could certainly be an attorney, but it could also be a digital estate planning platform where the client can implement the plan themselves.

Additionally, creating documents isn't the only way an estate plan can come together. Tools exist for advisors to help clients see how their current estate is structured and what potential planning gaps exist that need to be addressed. By knowing all the 'arrows in their quiver', advisors can be in the best position to help provide a truly holistic financial planning experience for clients without getting themselves in trouble.

What A Digital Estate Planning Platform Does

First, it is important to know what digital estate planning solutions actually do. Today, digital estate planning solutions exist in a variety of forms and offer various services to advisors and their clients. Platforms generally assist clients in the following 3 main areas:

- Document creation;

- Document extraction; and

- Estate visualization.

Document creation tools produce the documents that form the basis of the estate plan. When it comes to document creation, estate planning software addresses the basic documents virtually every person should have as part of their estate plan. This could typically consist of revocable trusts, wills, powers of attorney, and health care documents. These tools typically address the 'low hanging fruit' of estate planning for clients who know they need an estate plan, have a relatively typical asset makeup and family dynamic, and would like to implement a plan without the high cost of an attorney.

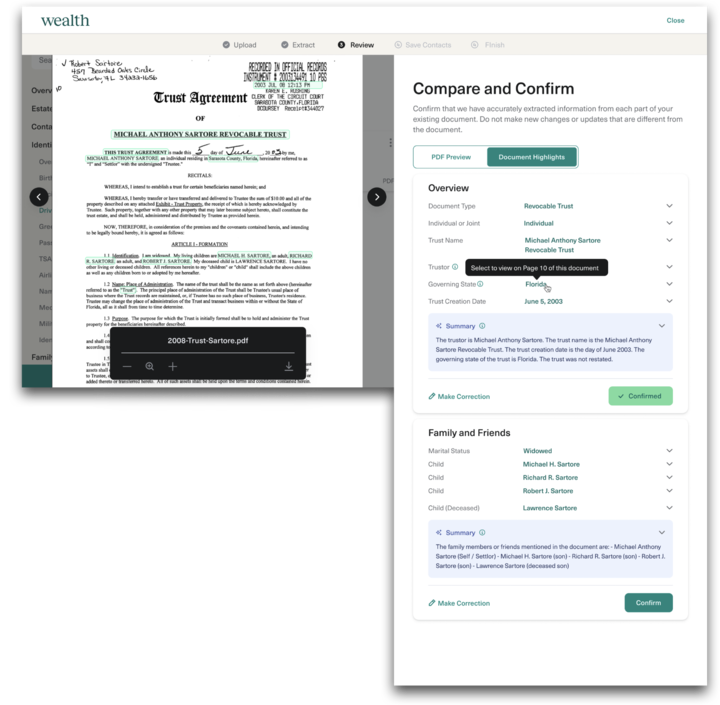

Document extraction tools provide summaries of existing estate plan documents based on information provided through human review or an artificial intelligence scan of plan documents. AI-based tools are powerful features that can assist advisors in understanding a client's estate plan document with incredible efficiency and scalability. Many people are aware of tools like Holistiplan that will read and summarize a tax document like Form 1040. Similarly, estate platforms may allow users to upload an estate plan document (such as a revocable trust), relying on AI technology to quickly analyze and summarize the document.

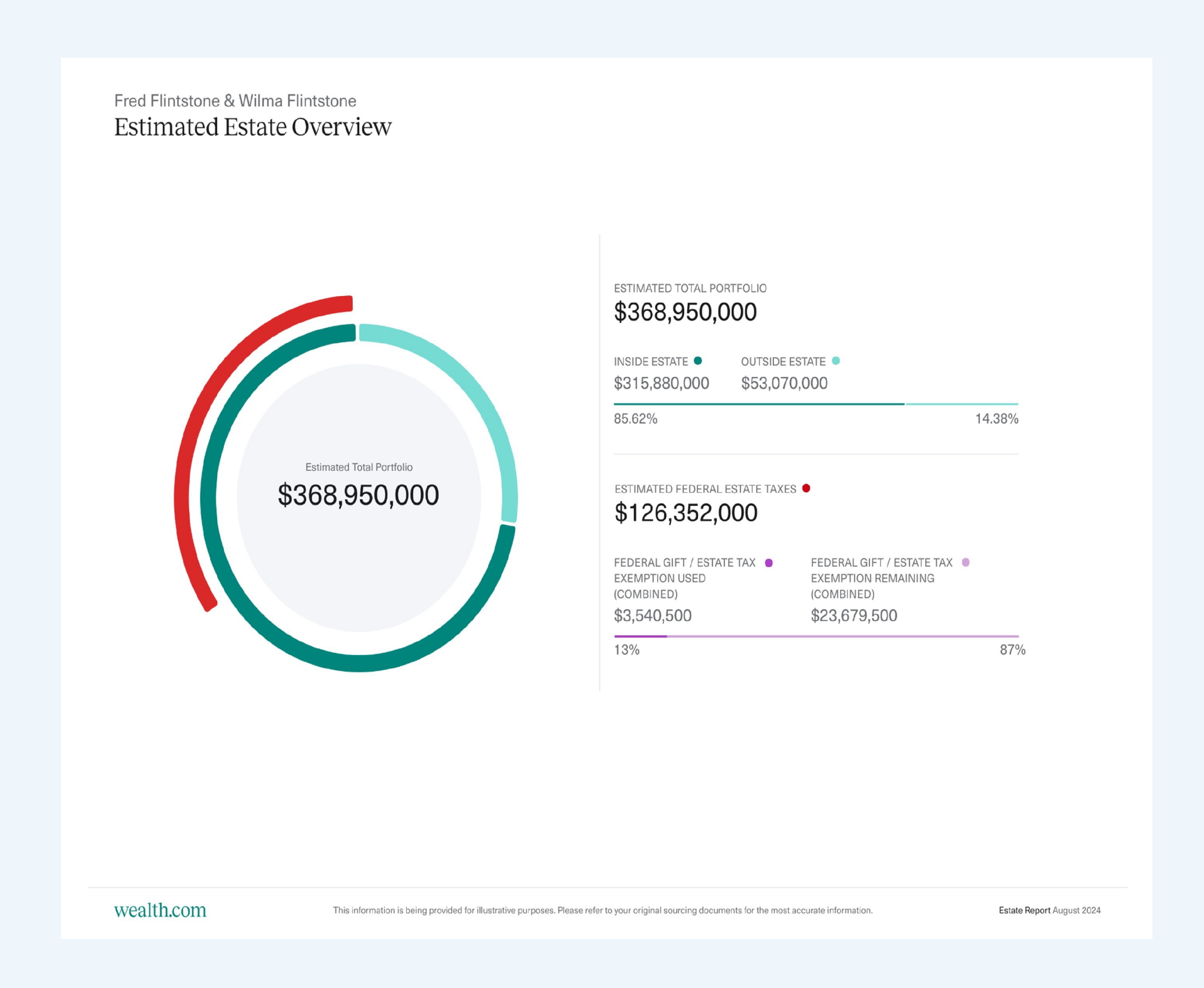

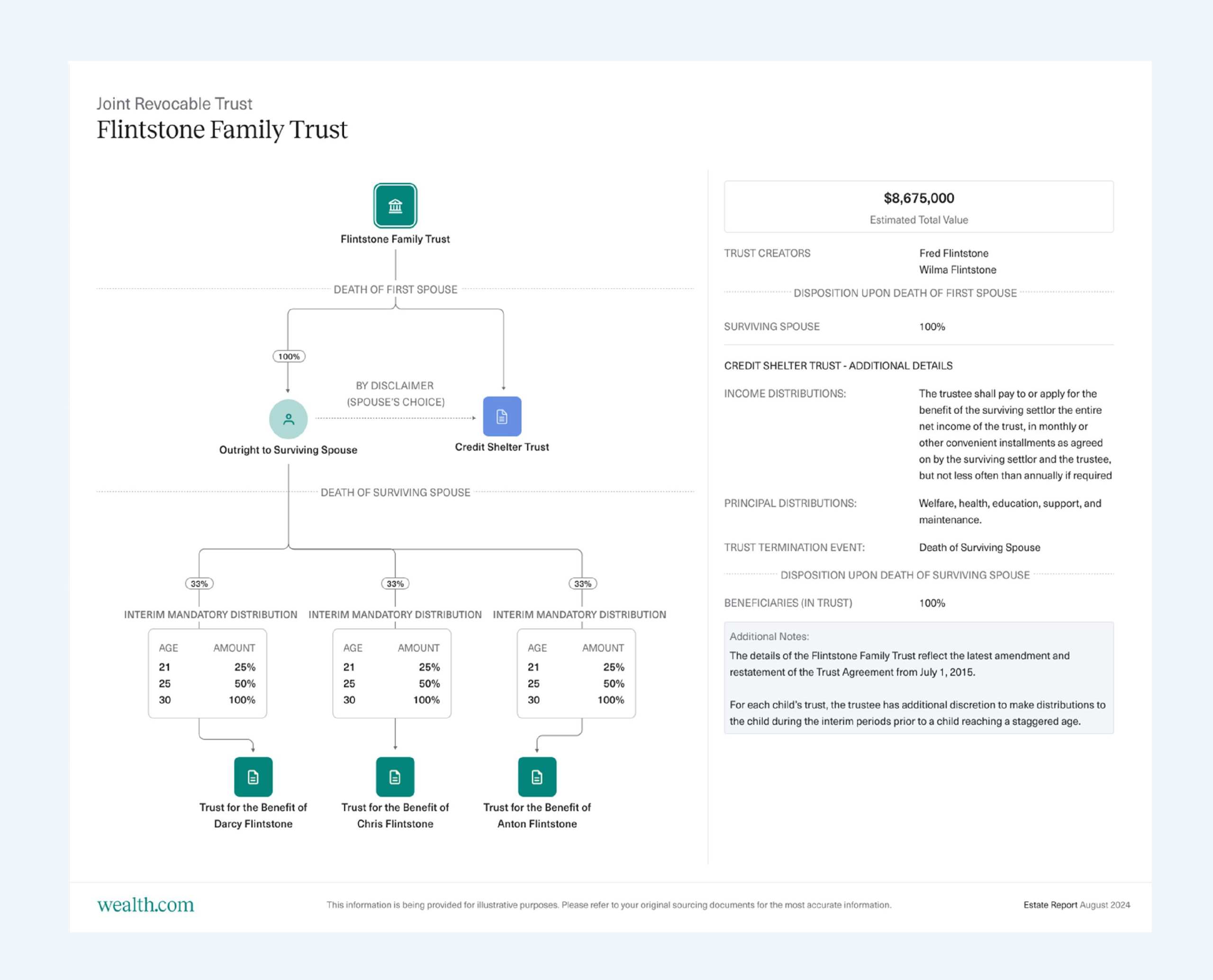

Estate visualization tools create a visual report that details the estate plan in a client-friendly manner. This process could involve taking in the data associated with the estate plan, organizing the information, and formatting the data into an attractive client deliverable. For example, visualization tools can lay out the specific details of a client's plan visually and explain core concepts using basic terms targeted for a lay user (e.g., what's inside versus outside the estate and what their potential estate tax liabilities could be).

The Historical Concerns Of Advisors Over Client Use Of Digital Estate Planning Platforms Versus Using An Attorney

The estate planning industry has seen many disruptions (and abuses). Norman Dacey's book represents one point in history when a disruption occurred, where Dacey presented an alternative approach to estate planning that challenged the then-popular reliance on the probate system. Another was the advent of trust mills in the 1990s, where non-lawyers were engaged in the business of selling living trusts to the aging population. Typically, this was done by inviting elderly individuals to seminars where presenters would hammer home how essential a living trust was, and then (typically) non-attorneys would create living trusts for the attendees for a fee.

You can think of the term "trust mills" in the context of a factory having individual employees pumping out a product at a high rate as if being made in a production mill. Although the basic legal practice of implementing a living trust was not seen as inherently problematic, the practice of these trust mills was seen as abusive and exploitative. The issue with trust mills was not confined to the preparation of the documents themselves; salespeople were also taking the financial information disclosed to them in the trust-creation process and using it to sell the client high-cost financial products (i.e., a bait and switch tactic). The exploitation of older individuals through trust mills became so rampant that it resulted in Congressional hearings on the matter. Even today, 'trust mills' remain a key focus of Attorney Generals in states concerned about elder abuse.

Then, in the 2000s, document creation platforms such as LegalZoom emerged for consumers to directly create a wide range of legal documents themselves, including estate planning documents. This raised questions about the role of software companies in legal advice and estate planning; for example, LegalZoom was subject to multiple allegations of the unauthorized practice of law over the last decade, and, more recently, the question has been raised of whether modern AI systems such as ChatGPT may be violating bar association rules on the unauthorized practice of law.

Many of the initial challenges could likely have been seen as knee-jerk resistance to new technologies disrupting the legal field and some concerns over whether the public could be harmed. These platforms offered a vast menu of legal documents involving a wide variety of areas of law, and there was heavy skepticism that the documents were comparable to those created through personal interaction with an attorney.

All of these historical issues have contributed to resistance and skepticism over digital solutions as compared to traditionally personalized professional services. Therefore, many advisors and compliance departments tread carefully when assessing new estate planning tools that are available to clients. Yet, at this point, similar to tax professionals who rely on technology tools for tax analysis and preparation, many estate planning professionals would now admit that digital platforms have become accepted as an inevitable part of society where users who resist them risk falling behind to competitors who choose to adopt them.

These points have also led to several concerns among the advisor community when it comes to using digital estate planning tools. Perhaps the most challenging is understanding and safeguarding against the unauthorized practice of law, but providing high-quality, relevant, and accurate services with digital tools are also common – and valid – concerns when considering whether to use digital estate planning solutions and how they might be implemented in the financial planning process.

Digital Estate Planning Solutions Might Engage Advisors In The "Unauthorized Practice Of Law"

While some advisor concerns are related to typical compliance matters related to the services provided by technology companies (such as information security and whether the company has a Service Organization Control Type 2, aka SOC 2), estate planning technology solutions add another category of concern for advisors providing estate planning services – the unauthorized practice of law.

The term "Unauthorized Practice of Law" (UPL) does not have a uniform definition and, therefore, can cause confusion for many non-lawyers concerned about wading into prohibited practice territory. The American Bar Association's comments on the rule that governs the unauthorized practice of law (Rule 5.5 in the ABA's Model Rules of Professional Conduct) state the following about how "the practice of law" is defined:

The definition of the practice of law is established by law and varies from one jurisdiction to another. Whatever the definition, limiting the practice of law to members of the bar protects the public against rendition of legal services by unqualified persons.

Accordingly, this flexibility across legal jurisdictions means that individuals need to be cognizant that no single definition applies across the nation and, when it comes to digital technology, that software companies may also be subject to different rules around what it means to practice law. This can influence how companies develop processes and guidelines to protect not only the company but also the people who use their services and products from crossing the line into the unauthorized practice of law (whatever that means for their particular jurisdiction).

Depending on the state jurisdiction, the penalty for the Unauthorized Practice of Law (UPL) can vary. State bar associations typically serve as major authorities in interpreting and enforcing UPL laws.

Non-attorney professionals in many disciplines have been tiptoeing around UPL concerns for years. Realtors, for example, have been long familiar with UPL rules due to the nature of their work, which can include helping clients with home sale documents. Accordingly, realtors may tread lightly when it comes to actually attempting to craft the language of a purchase and sale agreement, but in general, they may insert factual information into a legal form to assist the client.

Advisors run into similar challenges when determining where the line is for UPL when assisting a client with financial planning. Advisors routinely assist clients with a variety of issues that touch areas generally reserved for specific licensed professionals (e.g.,taxes or the law). Although disclaimers to the client at the point of service may cure many ills, the simple insertion of a disclaimer at the bottom of an email signature may not be sufficient protection from claims of practicing without a license.

From a public policy perspective, statutes and rules relating to UPL are typically designed to protect the public from receiving bad advice that leads them into a disadvantageous position. However, there is an anti-competitive motive at play – making sure that technological advances that help the public are not blocked due to laws and practitioners rendered obsolete by such advances. To this end, the law has struggled to reach a proper balance between promoting affordable technological advances that increase access to legal services versus protecting the public from unscrupulous individuals and companies providing less than adequate legal assistance.

Since this line has been so difficult to walk, the answer for advisors has typically been to be as careful as possible. However, with the rapid advances in technologies and available financial planning tools to attract and retain clients, advisors who are overly cautious risk finding themselves at a competitive disadvantage. Encouragingly, estate planning platforms, for the most part, hear these concerns and have made platform design choices that help protect the advisor from engaging in UPL (as will be discussed later).

Technology Solutions Might Create Estate Planning Documents That Are Too Generic To Address A Client's Specific Situation

Advisors may sometimes consider software that creates estate planning documents as a 'one size fits all' solution that cannot possibly be tailored to a client's unique situation. After all, no 2 clients are the same. They have different family dynamics, net worths, asset types, priorities, concerns (and the list goes on).

This concern is likely due to past reviews of documents prepared by 'do-it-yourself' legal document preparation platforms and 'take-on-all-comers' general practice attorneys trying their hand with estate plan documents. When the source creating the estate plan document is not well-versed in estate planning laws and trends (including those related to the client's state of residence), then documents can be overly generic to the detriment of the client.

Accordingly, it is critical for companies developing estate planning technology to ensure that the documents generated are initially crafted by highly competent estate planning attorneys and tailored to comply with the laws and local practices of the user's specific state of residence.

The Risk Of User Error Is Higher Without The Involvement Of An Attorney

Without an attorney involved in drafting and proofreading the documents, some advisors are concerned that clients may unwittingly wreak havoc on their plans. User error could come in the form of something as minor as misspelled names or as major as implementing an improper overall plan.

For example, a resident of Florida could decide they are in need of a power of attorney in case they become incapacitated and cannot manage their own affairs. Therefore, they go online and find a power of attorney that can be created through a website identified through a Google search. They had read that a "Springing Power of Attorney" would only become effective upon their incapacity, rather than being immediately effective. This sounded ideal, because they wouldn't want anyone accessing their accounts while they were still capable of managing their finances on their own. So, they go through the process and create their springing power of attorney thinking, "Mission accomplished!" The problem? Florida doesn't recognize springing powers of attorney as legally effective! So, the power of attorney (which may be otherwise useful in another state) is not worth the paper it is written on in this individual's state of residency.

The risk of such errors can often come down to the sophistication of the technology platform and the available guardrails to ensure the client doesn't travel too far down the wrong path. In this case, it would have been ideal for either the individual setting up a springing power of attorney to be alerted that they were potentially creating an invalid document for their state of residency or, even better, that the platform would deliver only the appropriate state-specific documentation.

How The Rise Of The Digital Estate Planning Platform Addresses Advisor Concerns

Estate planning platforms that recognize UPL as a top concern of advisors and compliance departments assessing the space will provide guardrails to protect against violating UPL rules. Accordingly, UPL concerns can typically be addressed by the platform if they ensure that the user (i.e., the client, not the advisor) controls the experience and makes legally effective decisions based on their own objectives and circumstances.

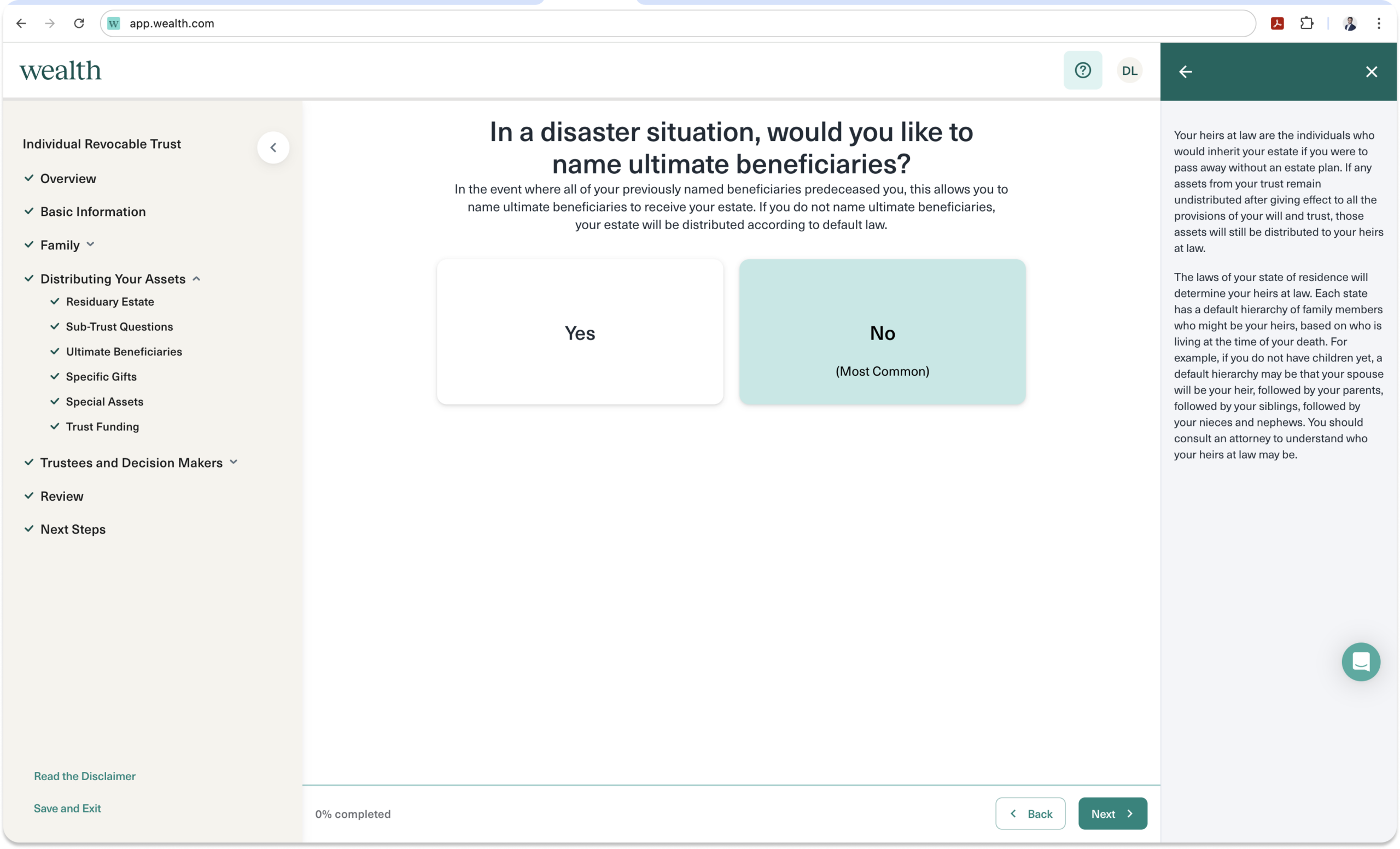

On an estate planning platform like Wealth.com, the client themselves arrives at the appropriate estate plan solution after being presented with estate plan design choices based on their personal factual circumstances and objectives (rather than a direct recommendation).

For example, rather than asking a user, "Do you want a Marital Trust?" (which requires understanding the legal construct of a marital trust and knowing how to apply it to their own circumstances, the platform might instead ask, "Do you have a net worth approaching or surpassing $6 million?" and "Do you worry that your spouse could disinherit your preferred beneficiaries?". This approach of using questions that examine a client's actual circumstances lessens the burden of legal jargon on the client (and, in turn, the client's reliance on the advisor to make a legal determination) to understand how legal concepts apply to them.

Instead, the client can consider a factual question about their net worth and whether a goal of theirs is to put some fetters around the spousal inheritance. The client then evaluates the applicable pros and cons of including a Marital Trust and can choose either to implement that strategy or to explore other estate planning forms. If a more detailed discussion is needed, the client also has the opportunity to obtain legal advice by accessing Wealth.com's vetted network of attorneys through the platform.

Additionally, platforms may provide document outputs for clients themselves to implement their estate plans, which can shield the advisor from becoming involved in a way that would create UPL concerns. An advisor should steer clear of recommending a client implement specific legal documents to accomplish their objectives. Rather, an advisor should uncover the client's goals and priorities and help direct them to a place where they can guide themselves to the appropriate legal solution.

For example, if an advisor said to a client, "I have reviewed your asset makeup, and I recommend you immediately put your assets into a spousal lifetime access trust for estate tax planning purposes", this would pretty obviously consist of providing legal advice because a direct recommendation to implement a legal strategy was provided to the client based on their personal circumstances.

However, the advisor could instead say, "I have reviewed your asset makeup, and it would appear you may have a potential estate tax issue. It may be a good idea to look into whether a spousal lifetime access trust could make sense for you. Here are some general resources on what a spousal lifetime access trust is; you can decide whether to seek out resources to implement this strategy". By taking this deferential approach, the advisor offers informative guidance and provides resources available to the client, but the onus is on the client to implement the strategy on their own.

It is important to note that while non-lawyers who provide direct recommendations can run afoul of UPL rules, providing general information on legal concepts should not be viewed as such. If non-lawyer advisors were prohibited from educating the public on legal concepts, then every webinar, college lecture, or estate planning article could be viewed as providing personal legal advice. It is typically only when a specific legal recommendation is presented to an individual based on their own unique circumstances that a person could be stepping over the line into offering legal advice.

Accordingly, while the advisor plays a key role in the estate planning process, the role should be limited when it comes to the implementation of the plan. Certainly, the advisor can (and should) have a visible role in the planning process and in monitoring whether the client has completed their plan, but the advisor should not be active in guiding the client's decision-making process when implementing the plan. Luckily, estate planning platforms can provide guardrails that restrict an advisor's access to a client's account and the level of interaction they may have. This helps create a "UPL firewall" between the advisor and client while the client uses technology tools to craft their estate plan documents.

Using Estate Plan Software Without Substantial Risk Of Error And/Or Advisor Liability

One key criticism of estate plan creation software has been that it results in a "boilerplate" estate plan. The term "boilerplate" has received a negative connotation, suggesting that a document is not sufficiently tailored to a person's unique circumstances. This has resulted in some clients saying, "I don't want boilerplate documents".

However, "boilerplate" isn't necessarily a bad word. Advisors can help clients realize that, in most circumstances, they actually do want boilerplate language in their estate plan documents. Such language is used because it is more likely to withstand legal scrutiny and is time-tested as consisting of legally valid and enforceable provisions. Therefore, many legal documents are simply a collection of reused, standardized provisions selected to meet a client's objectives. This is in contrast to provisions that are custom drafted or created 'freehand' where such provision has likely yet to meet a legal objection to determine whether it will stand as valid. Accordingly, the more creative the document, the more it is prone to human error and/or the more likely that the drafting could result in dispute/invalidation.

Take the example of a client who requests that their child does not receive any distributions if they have "committed a crime" (a real word-for-word client request I've received). Drafting a provision for that is challenging. What constitutes a crime? Only felonies? Misdemeanors? Getting a speeding ticket? And what’s the standard of verification – convictions only? What if they entered a "no contest" plea? The questions are endless. And therein lies the issue with diverting from the ‘time-tested’ discretionary language in boilerplate text and attempting to customize the wording. It can certainly be warranted, but it does carry a level of risk.

Just about every legal document generated today is likely produced by some kind of software program, and the wording may or may not have been altered by the professional creating the document. Many attorneys rely on software programs such as WealthCounsel to input client information and create estate plan documents like wills and trusts. Others may simply engage in 'Find and Replace' tools in a Microsoft Word document template to create estate plans. The point is that attorneys utilize much of the same type of technology as digital estate planning platforms to generate estate plan documents – only often the software the attorney utilizes is less sophisticated.

The key difference between a digital estate document creation platform and a law office is that the attorney (or, more likely, their paralegal) guides the information through the program and can physically amend the document once it is produced. However, as discussed above, attorneys often prefer to stick to the reliability of boilerplate language rather than risk the liability of custom drafting a provision into the plan. Additionally, if the client requires custom legal drafting to accomplish their goals, then they may not be a great candidate for a digital estate planning platform anyway.

AI Used Primarily For Efficiency (And Not Blindly Relied On) Can Reduce The Risk Of Error

"Artificial intelligence" is an accurate, overused, and misunderstood term when it comes to estate planning tech. Certainly, AI has represented a game-changing feature of estate planning platforms when it comes to document extraction. However, it is important to understand how AI does (and does not) come into play with estate planning platforms.

For document creation, AI should not be a substantial feature of the technology. As discussed above, the standardization of estate planning documents means that many clients do not require custom drafting and, therefore, the language used to create the estate plan is often static and does not rely on AI to create any new language to be added to documents.

However, for document extraction, the platforms may use AI-based Language Learning Models (LLMs) to interpret documents and extract key information in much more sophisticated ways than purely using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) functions (which many document scanning tools rely on) to read the plain text. When properly supervised, AI can be an invaluable tool for efficiency that helps advisors and/or their clients quickly read and summarize estate planning documents that can be lengthy and complex.

Notably, though, some AI tools like ChatGPT have created some concern in the legal field, famously resulting in the sanctioning of lawyers for citing fake cases in legal briefs to a judge. This is clearly concerning, which is why understanding what AI should and should not be used for is essential. AI is most beneficial when used as a helpful co-pilot that can assist the advisor in being more efficient in their document review process rather than as a tool capable of 'running the show'. Accordingly, validating all AI-extracted information is a crucial step when using digital estate planning platforms, rather than blindly relying on its accuracy.

Why Digital Estate Planning Platforms Will Not Replace Attorneys But, Rather, Complement Them

While the advisor concerns discussed earlier are historically well-founded, estate tech platforms have taken these concerns to heart, making intense efforts to address many of them in ways that alleviate advisor angst. They have also worked to enhance the availability of estate planning solutions to clients without compromising the important roles that their attorneys – or their advisors – play in helping guide their clients to find those solutions.

Digital Solutions Have Limitations That Still Necessitate The Services Of Attorneys

Digital solutions can only take a client so far; even the most sophisticated estate plan document creation platforms are not a replacement for the guidance and expertise of an attorney, especially in the case of a complex estate. The term "complex" can come in many forms.

The following are some typical scenarios where an estate plan may be better suited for the client's personal attorney to custom draft:

- A beneficiary is disabled and in need of "special needs" trust planning to preserve access to government benefits;

- The client is high-net-worth or ultra-high-net-worth and is in need of sophisticated estate planning involving the use of irrevocable trusts;

- The client desires to institute an asset protection plan to ensure Medicaid eligibility in the event of future long-term care in a skilled nursing facility; or

- The client has unique family dynamics, assets, or priorities that necessitate custom drafting in the estate plan to accomplish their goals.

Clients Will Still Need To Rely On Attorneys For Sound Legal Advice

Even in scenarios where a client's estate planning needs align with the capabilities of an estate document creation platform, the client may have questions about their plan or documents to guide them to the best choices or to confirm they are implementing the best plan for their situation. While the platform can provide a lot of general information to inform and educate on legal concepts, it cannot provide specific advice tailored to the client's personal situation (see the many references to UPL herein!).

Therefore, when a client requires advice or recommendations on their personal situation and estate, the client should reach out to an attorney to provide guidance to avoid implementing a plan through a digital estate planning platform that may not be best suited to them, even if the attorney does not ultimately create the documents. Estate platforms, like Wealth.com, may provide the option for the client to consult a vetted attorney within their network to get guidance on their estate.

Attorneys Serve Critical Functions Beyond Creating Estate Plan Documents

Even in scenarios where a client creates their estate plan through a digital estate planning platform, that doesn't mean an attorney won't still be a requisite part of the process in that plan. Once an estate plan based on a revocable trust is formed, the trust typically needs to be funded during the client's lifetime to ensure that assets avoid probate and properly flow through the trust. This process often involves the preparation of deeds to transfer the ownership of any real property the client owns into the trust. It could also involve the assignment of business interests to the trust. These types of actions typically necessitate the use of a local attorney.

Additionally, once a client passes away, while the documents themselves may do the job of reducing administrative costs and making a decedent's wishes clear and legally binding, the client's family or heirs may still require assistance in legally administering the estate. This often requires an attorney who is well-versed and experienced in the local laws of the decedent's state of residency.

Concerns such as the violation of UPL rules, overly generic documents, and alienation of attorney COIs are logical concerns of advisors who are assessing whether to add digital estate planning software to their tech stack. However, reviewing the advances aimed to alleviate those concerns and the guardrails put in place to safeguard advisors and clients against making errors can be an effective strategy to help advisors decide whether (and how) these digital tools can benefit them.

Given the shockingly high percentage of clients who don't have estate plans (and who need them), advisors who entertain digital estate planning solutions for clients can be confident that they are providing accessible and affordable options for clients with less complex estate planning needs.