Executive Summary

One of the key benefits of Social Security is the spousal benefit – a payment at retirement that goes not to the worker who paid into Social Security over time, but his/her spouse. The payment was originally designed to provide retirement support for what were typically (at the time) stay-at-home spouses in a single-income household, and still remains relevant today for many spouses who take at least some time off from work to raise a family.

However, the spousal benefit is not only available for currently married couples; single people who were previously married may also be entitled to a spousal benefit, based on the ex-spouse’s earnings record. This spousal benefit for divorcees becomes available as long as the couple was married for at least 10 years, and the divorcee has not remarried.

For some divorcees, the ex-spouse’s spousal benefit is a key pillar of retirement income, and choosing when to start the benefit – early at a reduced amount, or at full retirement age for the full amount – is a crucial decision. For others, the ex-spousal benefit will ultimately be trumped the divorcee’s own retirement benefit from years of working. But for those born in 1953 or earlier, who are eligible for retirement and (ex-)spouse benefits, there is still an opportunity to further leverage the spousal benefit by filing a Restricted Application for just the ex-spouse’s benefit at full retirement age, and switching to his/her own individual benefit at age 70 – increased by 32% Delayed Retirement Credits!

For some divorcees, though, the biggest opportunity of the ex-spouse’s spousal benefit is simply recognizing when it’s available, and claiming it properly, as if the ex-spouse’s benefit is larger, the divorcee can actually step up his/her benefit to the higher amount!

Example. Jim and Mary were married for 22 years while raising a family, and during most of that time Mary was a stay-at-home mother. The couple divorced 5 years ago when Jim and Mary were both 57, and now as Mary reaches age 62, she is wondering whether/what Social Security benefits she may be entitled to as a divorcee.

Spousal Benefits For Married Couples and Divorced Ex-Spouses

Anyone who works and earns at least 40 Social Security credits (generally by working at least 10 years) is entitled for a Social Security retirement benefit. The full benefit – called the individual’s Primary Insurance Amount (PIA), and based on his/her historical earnings record – is payable at his/her full retirement age (FRA).

In addition, a worker’s spouse may be entitled to a spousal benefit, which is 50% of the worker’s PIA. The benefit was intended primarily to help cover stay-at-home spouses in a single-income household.

In the event that both members of the couple worked, technically they may be entitled to both his/her own individual retirement benefit and a spousal benefit. Although, ultimately, Social Security will only pay to each person whichever amount is higher, not the cumulative total of both. (Technically, the retirement benefit is always paid first, and then an additional benefit is paid to increase total payments up to the spousal benefit level, if the spousal benefit is the higher of the two.)

Example. Assume Jim and Mary are still married. Jim’s full Social Security benefit is $2,000/month, and Mary’s is $800/month (as she took several years out of the workforce to raise the children). Mary will be entitled to both her own $800 retirement benefit, and a $1,000/month spousal benefit (50% of Jim’s benefits). However, since Mary can only get the higher of the two, she will ultimately receive $1,000/month, which is her spousal benefit (technically by receiving her $800/month retirement benefit, and a $200/month supplement, paid out as a single $1,000/month check).

Notably, Jim will also be entitled for a spousal benefit of $400/month (50% of Mary’s benefit). However, since he is entitled for his own $2,000/month retirement benefit that is higher, he will simply receive his $2,000/month payment, and the spousal benefit is moot.

In the case of a divorced couple, a divorcee is actually still entitled to claim a spousal benefit based on the ex-spouse’s earnings record. And the benefit is calculated in the same manner – as 50% of the worker’s PIA, payable in full at the divorcee’s full retirement age. And if the divorcee is entitled for his/her own retirement benefit, again, the divorcee will receive the higher of the two (not both cumulatively).

Example. Given that Jim and Mary are divorced, Mary will still be entitled to a $1,000/month ex-spouse’s spousal benefit. Since that amount is higher than her $800/month retirement benefit, as a divorcee she can still claim the full $1,000/month ex-spouse’s spousal benefit, upon reaching eligibility.

Entitlement And Eligibility For Divorcee Spousal Benefits

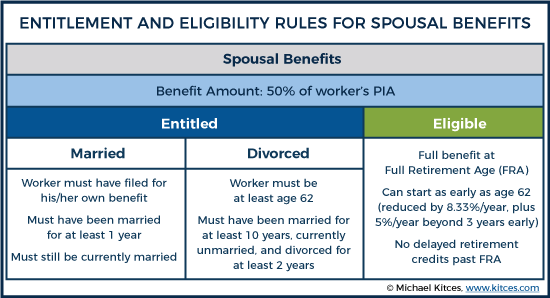

To claim a spousal benefit – whether as a current spouse, or a divorced spouse – the recipient must be both entitled and eligible for the benefit.

Being “entitled” means that the spouse (or divorcee) must qualify for a spousal benefit.

In the case of married couples, this means the couple must have been married for at least 1 year, must still be married, and, most importantly, the worker spouse must have actually filed for his/her own benefits. In other words, the spouse can only receive a spousal benefit when the primary worker is receiving his/her own individual retirement benefit as well. (In the past, it was possible for a worker to “file and suspend” to make a spouse entitled to spousal benefits, while not receiving his/her own retirement benefits, but those rules lapsed after April 29 of 2016 under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015.)

Example. If Jim and Mary were still married, then Mary may be entitled to a $1,000/month spousal benefit, but she can’t actually get her $1,000/month spousal check until Jim files for his retirement benefits as well. If Mary files but Jim hasn’t filed yet, she’ll get her $800/month retirement benefit for now, and will then step up to the full $1,000/month benefit later, once Jim actually files.

In the case of a divorced couple, the entitlement rules for spousal benefits are slightly different. For the divorcee to claim, the marriage must have (previously) lasted for at least 10 years, the divorce must have been at least 2 years ago, the divorcee must be currently unmarried (although the ex-spouse may have remarried), and the worker ex-spouse must be at least age 62. Notably, with a divorced couple, this means the worker spouse doesn’t have to actually have filed (as is the case if they couple is married); the worker (ex-)spouse must just be at least age 62, such that he/she could have filed.

In addition, to actually claim a spousal benefit, it’s also necessary to be age-eligible for it. To be eligible, the spouse/divorcee must be at least at age 62 to claim a spousal benefit, though the benefit is reduced (by 8.33%/year for the first 3 years early, and 5%/year for each additional year) if claimed that early. To receive the full spousal benefit, the spouse/divorcee must be full retirement age. (Special eligibility rules apply if there is a child in the household who is under age 16 or disabled.)

Notably, in order to claim a spousal benefit, the claimant must be both entitled and eligible.

Example. Because Jim and Mary were married for at least 10 years before their divorce, Mary will be entitled to a divorcee spousal benefit because Jim is at least age 62. However, Mary would not be eligible to claim that divorcee spousal benefit until she is also age 62.

Thus, for instance, if Jim were several years younger, Mary might be “stuck” waiting until her mid-60s or later, for Jim to reach age 62.

Similarly, Mary were several years younger than Jim, she might become entitled to a divorcee spousal benefit once Jim turns 62, but she couldn’t claim it until she ultimately turned 62 herself.

And in any case, if Mary claims as early as age 62, her spousal benefits will be reduced by 30% (for starting 4 years early), to only $700/month. To receive her full $1,000/month, she must wait until her full retirement age.

In the case of spousal benefits, while there is a reduction for starting early, there is no benefit (i.e., no Delayed Retirement Credits) for delaying past Full Retirement Age.

The Impact Of Remarriage On Divorcee Spousal Benefits

When it comes to ex-spouse’s spousal benefits for a divorcee, the whole point is that they’re benefits for an “ex-spouse”, not someone who’s currently married. After all, if you’re currently married – or in this context, remarried – you wouldn’t “need” an ex-spouse’s benefits, because you can get a current spouse’s benefits under the current rules instead.

As a result, a divorcee can only have ex-spouse’s spousal benefits as long as the divorcee remains unmarried. If the divorcee gets remarried, the ex-spouse’s spousal benefits will stop. Of course, the newly remarried divorcee may now become re-eligible for spousal benefits based on the current spouse. But that will depend on whether the newly married divorcee is entitled (and in particular, whether the new spouse is actually taking benefits themselves to render entitlement).

However, it’s important to note that the only remarriage that matters is the divorcee’s remarriage. If the ex-spouse remarries, it doesn’t impact the divorcee’s benefit. In fact, the ex-spouse could wind up funding a spousal benefit to the new wife and the divorcee simultaneously (each of whom are entitled to full spousal benefits).

Example. Given that Jim and Mary are divorced, but their prior marriage lasted for at least 10 years, Mary will be entitled to an ex-spouse’s spousal benefit because she is currently unmarried. If Mary remarries Donald, though, she will simply be entitled to a spousal benefit from Donald in the future, instead of an ex-spouse’s benefit from Jim.

On the other hand, even if Jim remarries, Mary will remain entitled for her ex-spouse’s benefit, in addition to the fact that Jim’s new wife may be entitled for her own spousal benefit as well. The fact that Mary does or does not claim a spousal benefit has no impact on timing or amount of spousal benefits for Jim’s new wife (or vice versa).

Notably, in scenarios where there are multiple remarriages and multiple divorces, a divorcee may become eligible for multiple ex-spouse benefits (as long as the marriage to each ex-spouse lasted for at least 10 years apiece). In such scenarios, the divorcee can receive benefits based on whichever ex-spouse gives the biggest/best benefit (but not all of them cumulatively).

Example. Continuing the prior scenario, if Mary’s new marriage to Donald lasts at least 10 years and then ends in divorce, in the future, Mary will become entitled to an ex-spouse’s spousal benefit from both Jim and Donald. In that case, she will receive whichever is the larger ex-spouse benefit. (Though if her own individual retirement benefits are larger, those will still overwrite all ex-spouse’s benefits.)

Claiming Strategies For Divorced Ex-Spouses

While the reality is that a divorcee either will or will not be entitled and eligible for ex-spouse spousal benefits – the rules are what they are – claiming strategies are still relevant, because divorcee’s still have to make a decision about when to claim available benefits.

At the least, there’s a timing decision for spousal benefits about whether to start early or delay to Full Retirement Age, and for divorcees who may be also eligible for their own individual retirement benefits, coordination strategies across multiple benefits become relevant as well.

Relying On Ex-Spouse Spousal Benefits Alone

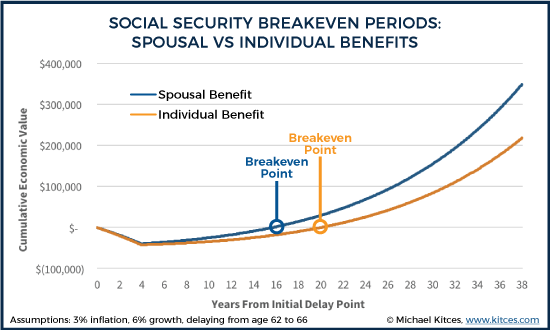

For divorcees who are solely entitled to ex-spouse spousal benefits (i.e., never having worked enough to have individual retirement benefits as well), the only decision is whether to start early (as early as age 62) or wait until full retirement age. The benefit of waiting is that the (ex-)spousal payments will be larger (by avoiding the reduction for starting early); the bad news is that no payments are made during the waiting period, so the divorcee must live long enough to make up for the years’ worth of foregone payments with the higher checks that come with waiting.

Example. Mary’s spousal benefit may be $1,000/month, but she can only get the full $1,000/month amount if she waits until her full retirement age (assumed to be age 66 for now). If Mary starts at age 62, her spousal benefit will be reduced by 30% to only $700/month, because she began her payments 4 years early.

Accordingly, Mary must decide if it’s preferable to get $700/month now, or $1,000/month starting in four years, recognizing that if she waits the four years, she’ll miss out on $33,600 of payments (plus a little more for ongoing Cost-Of-Living Adjustments) during the waiting period! Which means she’ll need to live a long ways past age 66, just to make up the $33,600 shortfall by collecting an extra $300/month (plus COLAs) for each year thereafter!

In reality, this type of “breakeven” analysis – how many years of larger payments must be received to make up for the early years when no benefits were paid – is necessary for anyone entitled to a Social Security benefit, whether as an individual retirement benefit or a spousal benefit.

Though the “good” news is that because the early benefits reduction is more severe for spousal benefits (starting at age 62 with FRA of 66 is a 30% reduction) than for individual retirement benefits (which is only a 25% reduction for starting 4 years early), delaying a spousal benefit to at least full retirement age is slightly more valuable for the divorcee, and the breakeven period is shorter.

In essence, as long as the divorcee believes he/she can survive the breakeven age, it’s beneficial to delay an ex-spouse’s spousal benefit. To the extent that the divorcee lives materially longer, inflation is higher, and/or market returns are lower, the decision to delay will look even better. Especially if the divorcee is actually now working, as the Earnings Test can partially or fully reduce spousal benefits for those who apply early and earn more than $16,920/year (in 2017).

Notably, though, because there are no Delayed Retirement Credits for starting later than full retirement age (as those apply only for an individual’s own retirement benefit), and the Earnings Test also ends at full retirement age, the latest a divorcee should ever delay a spousal benefit is simply up to full retirement age.

Coordinating Ex-Spouse Spousal Benefits And Retirement Benefits

For those divorcees who also worked and are entitled to their own retirement benefit in addition to an ex-spouse’s spousal benefit, there are more benefits available, but not necessarily much more flexibility in claiming choices.

The reason is the so-called “deemed filing” rule, which stipulates that anytime someone is eligible for both an individual and a spousal benefit (including an ex-spouse’s spousal benefit), they are “deemed” to file for all available benefits. And as usual, any time an individual applies for multiple benefits, they don’t get all the benefits cumulatively; they get whichever pays the highest amount.

In turn, this means that if there is a retirement and spousal benefit, and the retirement benefit is higher, the divorcee’s (ex-)spousal benefit is a moot point. At the point the divorcee is eligible for the spousal benefit, he/she will already be eligible for the (higher) retirement benefit, and the retirement benefit will overwrite the spousal benefit. As a result, the decision really just falls back to the standard analysis that applies to any individual who is considering whether to start retirement benefits early, which is evaluated by considering the breakeven period, the benefits of delaying, and the potential impact of the Earnings Test.

On the other hand, if the divorcee’s (ex-)spousal benefit is higher, the reality is that the spousal benefit will still ‘overwrite’ the retirement benefit whenever benefits are applied for (which, again, will be a deemed application for both). However, there may be a time window where retirement benefits are paid and not spousal, simply because the divorcee was personally eligible for retirement (at least age 62) but not yet entitled to spousal (because the ex-spouse isn’t 62 yet). Still, though, any early reductions (if the divorcee files early) will still apply upon becoming entitled to the spousal benefits… which means it’s even less valuable to start early, because the divorcee will have the early reduction despite not getting the full early check!

Restricted Application For Divorcee Spousal Benefits

A special exception to coordinating benefits is available for those who are entitled to both retirement and spousal benefits, depending on the year in which they were born.

The technique, called a “Restricted Application for Spousal Benefits”, or just “Restricted Application” for short, was eliminated under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, but grandfathered if the divorcee was born in 1953 or earlier (or on January 1st of 1954).

The Restricted Application rules allow a spouse – including a divorcee ex-spouse – to file for any spousal benefits to which he/she is entitled, but only spousal benefits and not individual retirement benefits. This allows the divorcee to receive spousal benefit payments now, but still earn 8%/year Delayed Retirement Credits on the retirement benefits not received. In essence, the divorcee gets to enjoy all the benefits of delaying individual retirement payments to age 70, and get ex-spouse’s spousal benefits along the way!

Example. At her full retirement age, Mary chooses to file a Restricted Application to receive the spousal benefit from Jim, but not her own benefit. As a result, she begins to receive her $1,000/month checks immediately. At age 70, Mary’s individual benefit will have earn 8% x 4 years = 32% in delayed retirement credits, boosting her individual benefit to $1,056/month. As a result, she can then switch at age 70 to her individual retirement benefit, which now actually is the larger benefit, thanks to the opportunity to earn Delayed Retirement Credits.

The appeal of the Restricted Application strategy is that the divorcee can earn the entire 32% Delayed Retirement Credit on his/her retirement benefit, even as the spousal benefits are being paid along the way. In the example above, this effectively reduced the “cost” of waiting to zero, because Mary was already receiving her $1,000/month spousal benefits in the meantime anyway! Yet the delayed retirement credits were large enough to eventually make her retirement benefit the larger of the two.

On the other hand, the Restricted Application strategy for divorcees can be appealing even with a substantial personal retirement benefit, because it still reduces the implicit cost of waiting to earn Delayed Retirement Credits.

Example. Assume that Mary had a full-time career herself, and a $2,000/month retirement benefit, similar to Jim’s. Normally, this would make Mary’s $1,000/month spousal benefit moot, as her $2,000/month retirement benefit is already larger.

However, Mary can still choose to file a Restricted Application at her full retirement age, and begin to receive $1,000/month from age 66 to 70. In the meantime, she will earn 32% in delayed retirement credits, boosting her retirement benefit up to $2,640/month.

Of course, Mary could have simply waited four more years until age 70 anyway to boost her retirement benefit until to $2,640/month. But doing so would have ‘cost’ her $2,000/month x 4 years = $96,000. With the Restricted Application, though, Mary receives $1,000/month x 4 years = $48,000 of payments in the meantime. The end result is that Mary still gets 100% of the Delayed Retirement Credit benefit, but at only half the upfront out of pocket cost (which in turn drastically reduces the breakeven period to benefit from waiting, and the upside in the long run for having waited).

Notably, to file a Restricted Application, the divorcee must be at least full retirement age. The birth-year requirement simply determines whether the divorcee can do a restricted application upon reaching FRA; it’s still necessary to wait until FRA to do so. If the divorcee files for benefits early, it will again be a deemed filing application for all benefits – retirement and spousal – and the opportunity is lost.

For those who were born on January 2nd of 1954 or later, the restricted application rules are simply unavailable, having been eliminated by the rule change under the Bipartisan Budget Act.

Filing For Ex-Spouse’s Benefits Online

Divorcees can file for (ex-)spousal benefits either by visiting a local Social Security office or online via SSA.gov.

If filing online, the Social Security Administration will make a follow-up request for documentation to substantiate eligibility for the ex-spouse’s spousal benefits, including a birth certificate (to validate the divorcee’s age), marriage license (to validate the marriage), and divorce decree (to validate that the marriage met the 10-year requirement, and that the divorce was valid and legal).

For divorcees who intend to do a Restricted Application, be certain to request in the application process only the spousal benefit and not individual retirement benefits as well. It’s also advisable to note in the Remarks section (of the online application) that the intention is to file a “Restricted Application for [only] Spousal Benefits” and not individual retirement benefits as well.

So what do you think? Are divorcees aware of the claiming strategies available to them? Do you have a process for making sure a divorcee isn't missing out on a higher (ex-)spousal benefit? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!