Executive Summary

It is a staple of financial advising to measure a client's risk tolerance; whether out of a mere regulatory requirement to do so, or out of a best practices desire to better understand a client's comfort level with the investments (and other financial planning advice) being recommended, so process to measure risk tolerance is essential in today's world.

Yet many financial advisors severely question the value of doing so; as the saying goes, "Clients are risk tolerant in bull markets, and intolerant of risk in bear markets, so is there really that much value to going through the exercise at all?" And a recent academic presentation at the FPA Experience conference added fuel to the fire, showing a remarkably high correlation between the monthly average risk tolerance scores of a well respected measurement tool, and the monthly level of the S&P 500.

Yet a deeper look reveals that while even the best risk tolerance measuring process is not totally immune to the vicissitudes of the market, a client's true risk tolerance appears to be remarkably stable and doesn't change much at all in the midst of volatile markets. Instead, what appears to be unstable is not the client's tolerance for risk, but their perceptions of risk in the first place; in other words, clients may be loading up on stocks in bull markets not because they're more tolerant of risk, but because they don't think there is any risk in the first place. In turn, this suggests that ultimately, it may be time for financial planners to more widely adopt quality tools to measure risk tolerance, but simultaneously recognize that managing client (mis-)perceptions of risk is the real challenge that we face.

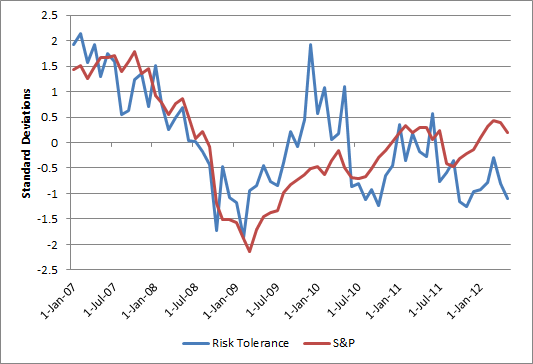

Inspiration for today's blog post is presentation from FPA Experience Academic Track (which was subsequently discussed on Wade Pfau's blog), where Texas Tech researchers Michael Guillemette and Michael Finke showed a version of the following chart, demonstrating a remarkably strong relationship between the average (monthly) risk tolerance score (RTS) and an index of the S&P 500 (on a total return basis).

As the chart above suggests, there is a high correlation between client risk tolerance, and the price level of an S&P 500 total return index. As the market declined in the midst of the financial crisis, average RTS declined, and as the market recovered, so too did average risk tolerance scores. In fact, the correlation between the two data series is a whopping 0.70.

Putting Risk Tolerance Volatility In Proper Context

Notably, the chart above is graphed on what's called a "standardized" scale, which means each set of data - for risk tolerance and for the S&P 500 total return - have been converted from their actual score ranges to a scale based on their standard deviations. The purpose of this conversion is, as the name implies, to view both sets of data next to each other on a "standardized" scale where each is measured relative to its own intrinsic volatility (as measured by standard deviation).

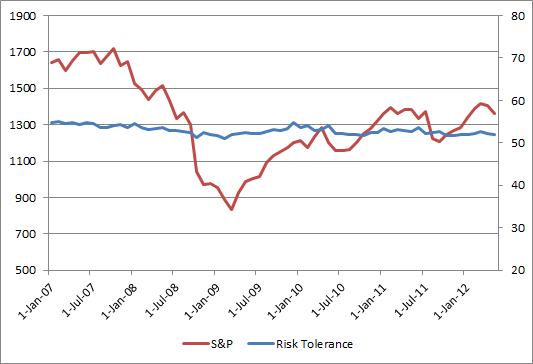

However, it can also be helpful to view the results in the context of their actual underlying scores... which in this case, paints a rather different picture, as illustrated below.

In this context, the results suddenly paint a very different picture. While risk tolerance scores do trend in the same general direction as the S&P 500 (graph includes total return, not just price), the stock market looks like a grand rollercoaster compared to the relatively benign ripples in risk tolerance scores; in part, this is because the scoring methodology for FinaMetrica is already a standardized scale (with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10), such that the researchers' decision to standardize an already-standardized scale may have been a methodological error that inappropriately amplified the apparent volatility of risk tolerance.

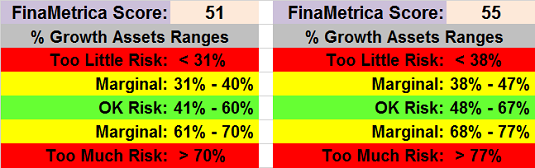

In fact, the entire range of risk tolerance scores over this time horizon spans from only 51 to 55 on a scale that can theoretically go all the way from 0 to 100 (though almost all scores fall between 20 and 80, which would be +/- 3 standard deviations). So just how mild is a four point swing? The FinaMetrica risk tolerance scoring structure is shown below:

In other words, with the stock market going through a nearly-50% decline followed by a nearly total recovery through the end of the time horizon (the data used for this analysis ended in early 2012), the "tolerable" equity allocation range would have changed only a few percent. For someone who started out with a middle score (e.g., a "53" on the FinaMetrica scale), moving up and down would have resulted in a 'recommended' asset allocation change of no more than about 3% up or down from the starting point. And of course, as FinaMetrica notes, risk tolerance scores are typically associated with a range of possible equity exposures; for a client that was already 50%-60% in equities, none of this mild volatility in risk tolerance scores would have even taken them out of the "OK" risk range into the "Marginal" range on the above chart, and certainly would not have taken the client to the point where there was outright too little or too much risk relative to the score.

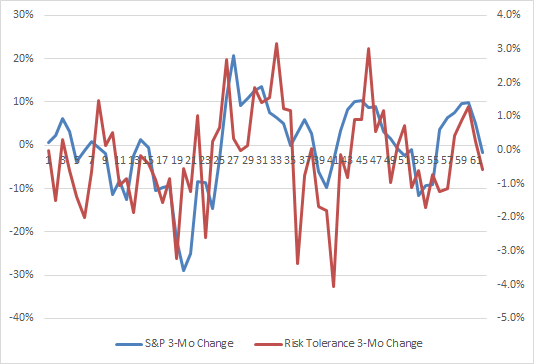

Simply put, if the S&P's volatility represented earthquakes, the associated changes in risk tolerance scores were no more than tiny ripples or aftershocks; enough that you might notice something happened, but not enough that you would actually advise doing anything about it! In fact, the chart below looks more specifically at the trailing 3-month price return of the S&P 500 total return, versus the 3-month change in FinaMetrica Risk Tolerance Scores. While once again the correlation is fairly high at 0.487 (notably, still less than the correlation between the absolutely level of the markets, suggesting that the "wealth effect" of feeling more or less affluent may impact tolerance even more than recent returns!), the scales are still dramatically different; every 10% change in the markets only moved the typical risk tolerance score by about 1.5%, which in turn translates to such a little change that the client's equity exposure wouldn't even be impacted given the score ranges on the FinaMetrica scale!

Volatility In Risk Tolerance, Or Risk Perception?

While the changes in risk tolerance through market cycles appear to be tiny when viewed in context, any planners who have dealt with clients through a full bull-and-bear market cycle have witnessed some pretty dramatic behavior changes as market returns come and go. Which raises the question - how do we reconcile what appears to be relatively stable risk tolerance in the charts above, where equity exposure would hardly change at all, with the rather unstable client behaviors around risk where they try to make dramatic changes in their asset allocation?

The key distinction is the difference between risk tolerance, and risk perception. Risk tolerance is meant to be a measure of a client's willingness to pursue a risky (financial) goal, in the hopes of getting a better outcome. It's a measurement of willingness to engage in potentially risky trade-offs.

Risk perception, by contrast, is a measure of how risky a client thinks their own behavior might be. It's the self-check we go through to ask "is the risk of the current behavior I'm engaged in consistent with the kinds of risks I'm comfortable taking?" Of course, the problem is that in general, we are remarkably poor at judging the risk of our own behaviors, due a wide range of now-well-documented behavioral finance biases that cause us to misjudge. The recency bias causes us to ignore the actual risks of our behavior and assume the recent past will continue into the future (bull markets will keep going up, bear markets will keep going down). Familiarity bias causes us to assume things with which we're more familiar must be less risky. Availability bias causes us to overestimate the risk of situations for which we can easily recall an example to memory (it's why the movie Jaws has left us thinking the risk of shark attacks is high, when in reality even for those living in the coastal United States it's almost 80 times more likely to be fatally struck by lightning than killed in a shark attack!).

Accordingly, this suggests that for clients who are difficult to manage in the midst of volatile markets, the problem is not likely to be their volatile risk tolerance (which is actually quite stable with only small changes), but their volatile risk perception, which can swing wildly as they constantly mis-judge the actual risk of their investment portfolios. In other words, clients didn't want to keep buying more technology stocks in 1999 because their risk tolerance had changed; they wanted to buy tech stocks in 1999 because they thought tech stocks provided risk-free double-digit returns that would extend indefinitely (availability bias, plus perhaps overconfidence in prior successful tech investments), which meant that even the most conservative clients loaded up (after all, what ultra-conservative client wouldn't want a "risk-free" 15%-25% annual return!?). Similarly, clients may tend to want to bail out of stocks in bear markets like the 2008-2009 financial crisis not because their tolerance for risk necessarily changed, but because they're afraid that stocks are going to decline to nothing. After all, if you're (mistakenly) convinced that the entire stock market are falling all the way to $0, you wouldn't want to own stocks regardless of how tolerant you are of risk, as even the most tolerant investor doesn't want to own something they're convinced is going to have a total loss!

Practical Implications - How Effectively Can Risk Tolerance Really Be Measured, Anyway?

Of course, the fact remains that, while the actual fluctuations in risk tolerance with market volatility are quite small, they remain nonetheless; the data does show that FinaMetrica risk tolerance scores are shifting based on the absolute level of the markets, and recent price changes.

Nonetheless, it still remains unclear whether the reality is that risk tolerance is actually changing with market results, or whether FinaMetrica is simply a not-quite-perfect measure of risk tolerance in the first place. After all, the reality is that measuring an abstract psychological trait like risk tolerance is difficult at best, especially when it's intended to be confined to the realm of investment risk tolerance in particular. Which means, simply put: is the correlation between risk tolerance scores and market activity a sign that risk tolerance isn't stable, or a sign that FinaMetrica hasn't quite managed to completely filter out market noise when trying to estimate a client's risk tolerance?

Similarly, at the aforementioned FPA Experience presentation, Guillemette and Finke showed that risk tolerance exhibits correlations to the overall P/E ratio of the stock market. To the extent the P/E ratio reflects investors perceptions of risk - willing to invest at higher P/E ratios when fears are low and demanding more favorable valuations and a "margin of safety" when perceived risks are high - their data showed a relationship between risk tolerance scores and P/E ratios, but it's still unclear that's because risk tolerance is actually unstable, or simply because FinaMetrica scores are not totally immune to the impact of risk perceptions.

Still, given the overall stability of FinaMetrica risk tolerance scores, the implication is that risk tolerance can be measured effectively (especially if the test is used as a starting point that is confirmed with a subsequent conversational process with the client), and the resultant scores can be relied upon by financial planners, as the magnitude of changes that are occurring are very mild. Similarly, even FinaMetrica acknowledges that there is some imprecision to the measurement process, which is why their FinaMetrica risk tolerance scores are associated with a range of recommended portfolios (or conversely, portfolios are associated with a range of risk tolerance scores), rather than a pure 1:1 relationship where a specific score of X means an exact equity exposure of Y.Y%. FinaMetrica itself suggests that risk tolerance itself should perhaps be viewed as a comfort "zone" rather than a specific target point, as illustrated in the graphic below.

The bottom line, though, is that in light of how stable even FinaMetrica scores are - even given the murkiness of trying to measure psychological traits - the preponderence of the evidence suggests that while markets may be volatile, risk tolerance is at least "mostly" stable (to the point where you shouldn't anticipate clients needing to change their portfolios due to risk tolerance score "wobble" in the midst of volatile markets). Of course, that doesn't mean we can afford to be hands-off with clients in the midst of market volatility - to the upside or the downside - but it does reinforce the conclusion that in the end, risk tolerance may be something that's stable enough to measure once as an anchor, but managing client risk perceptions - and mis-perceptions - is something we'll need to continue doing as long as we have clients who invest!

And there’s a double edged sword involved here too — the negative feedback loop of the market. The misperceptions of investors, believing the market was going to zero and staying there (resulting in panic selling) is largely what caused the market to go down in the first place.

I’ve never understood why the question is how much risk can you tolerate? That, to me, is like a doctor saying “you have cancer. how much pain can you take?” I would prefer the doctor to say “You have cancer. Here are the 4 options you have – chemo, radiation, surgery, nothing – and what their implications are for your specific case. In my professional opinion, here’s the risk you NEED to take (chemo and radiation) to cure the cancer. . [Here’s how much risk you need to take to meet your retirement goals.] Here’s the risk you can AFFORD to take (surgery would likely kill you). [You have no emergency fund and no disability insurance, so you shouldn’t invest everything in the stock market.] So here’s what I recommend. Now that you know your options and what they mean for you, then the question is “how much risk do you WANT to take?”

Jean,

Targeting portfolios based on “how much risk CAN you take” is not the proper use of risk tolerance tools. That’s the way FINRA regulators have often applied it, but that’s not actually how it should be done.

The point of risk tolerance is a CONSTRAINT. For example: “Your goals require that you grow your portfolio at 9%/year. That requires a portfolio so risky you’d throw yourself off a building [it grossly exceeds your risk tolerance].” The proper solution is not to invest to the client’s risk tolerance here; it’s to recognize that the mismatch between required risk (for goals) and risk tolerance dictates that the client find some new (more realistic) goals.

Conversely, if the scenario is “Well, it turns out you can tolerate a portfolio with 70% in equities, but after going through the financial planning process you clearly only need a portfolio with 30% in equities to achieve your goals” the proper allocation is 30%. It meets the client goals, and it’s within risk tolerance.

In either case, though, risk tolerance is not a target or goal itself, not should it ever be. It’s a constraint to recognize that certain portfolios – and certain goals themselves – may be beyond tolerable risk, requiring a reassessment of the whole portfolio and goal itself.

– Michael

Risk tolerance tools have always been used primarily as a way for advisors, compliance officers and financial institutions to protect themselves from liability. It is ridiculous on its surface to ever purport there could be a tool which would measure anyone’s tolerance for any kind of risk, including financial. The fact that my personality is relatively stable does give not any clue as to how I will act in any particular terrifying situation, nor is there a way to measure what I’m likely to do.

Russ,

The fact that risk tolerance tools have been grossly misused & distorted does not invalidate them or their usefulness.

Quality risk tolerance measures don’t guide HOW someone will act in a particular terrifying situation. They give an indication as to what will BE a terrifying situation for the client. Different clients have different levels of risk tolerance, and as a result vary greatly in what they find “terrifying” in the first place (which is also exacerbated by risk [mis]perception issues as well).

– Michael

Your article ”

Can We Really Measure Risk Tolerance Or Does It Swing Too Wildly With Market Volatility” is really worth reading!

Thanks,

Mith @ Accident Compensation

Unless your clients are engineer types, I find the most simplistic tool to evaluate “true” client risk tolerance is to have them tell you the maximum percentage their portfolio can draw down (peak to trough) without abandoning their “plan”. Understanding this max draw down sets expectations on both sides of the table.

Darryl,

Unfortunately, there’s virtually no evidence I’ve been able to find anywhere in research to substantiate that that’s an effective tool to measure tolerance. It presumes clients can predict how they will act in situations they’ve never experienced. Psychometrically designed risk tolerance questionnaires can examine behavior at large to draw parallels; clients on their own are guessing blind.

– Michael

I’ve always found funny the risk tolerance tools that measure tolerance in absolute terms. Isn’t it more valuable to gauge risk tolerance _relative_ to other investors? And not just similarly situate individual investors with professional advisors, but institutional, governmental, etc.? Seems like relative tolerance is where the rubber hits the road, i.e. are you more tolerant of risk than the next guy at that point in time or given a certain set of variables.

Stephen,

That’s why a properly designed risk tolerance questionnaire is necessary – NOT the crap that regulators typically use.

A psychometrically designed risk tolerance questionnaire goes through a norming process that helps to ensure its relative results on the scale are meaningful. We do this regularly in practice now with the FinaMetrica tool – it’s particularly helpful to highlight risk tolerance disparities with a couple, not only to see if/whether they’re different but HOW different they are.

– Michael

Thanks for the reply. Thinking in particular about the other half of my “couple” I can see how that would be incredibly interesting.

Perhaps the whole problem is with the concept of risk tolerance itself, defined as some kind of psychological, subjective state of mind? We ask our clients how much risk they are willing to accept or are comfortable in accepting. My view is that the only correct answer to this question is “none.” Why would anyone want to expose themselves to any risk? The answer of course is that they need to expose themselves to some amount of risk in order to meet their goals. But isn’t that our job, to define how much risk they “need” to take in order to get where they want to go?

Suppose we simply said: “In order to meet the various goals which you’ve defined, this is the asset allocation I recommend, and this is the amount of downside risk that allocation will expose you to.” Clients will either say that’s fine or they’ll say they don’t want that much downside, in which case we would ask them which of their goals they would like to reduce. At this level it’s a simple trade-off.

Admittedly, these calculations are not an exact science, but aren’t WE better qualified to come up with reasonable answers than our clients?

Thank you for bringing this issue to the discussion forefront. It is a simple reality that (1) what is conservative to one investor may be aggressive to another and (2) individual investor risk tolerance is a constantly moving target. The regulatory requirement to ask clients to state their risk tolerances is a loaded question. Most advisors will likely agree that their clients have a virtually unlimited tolerance for upside volatility, but considerably less for downside. Conversely, we have all likely had clients who have expressed a conservative risk tolerance but have virtually no chance of achieving their long term retirement objectives by investing at the “risk-free” rate.

Nest Egg Guru,

Thanks for the kind words.

But the “simple reality” as this article is trying to highlight is that yes, what is conservative to one investor is aggressive to another, but that is NOT a “constantly moving target” of risk tolerance. That is a constantly moving target of risk PERCEPTION, and it’s an entirely separate matter.

In fact, that’s the whole point of why an accurate measurement of risk TOLERANCE matters so much. If two clients are invested 100% in equities, and one has a high tolerance and the other has a low tolerance, measuring tolerance is how you know the first has an appropriate portfolio, and the second is actually MISPERCEIVING (and grossly underestimating) the risk of the portfolio and that it’s actually outside of tolerance.

Until we consistently and appropriately measure risk tolerance, we have no way of distinguishing those who mis-perceive risk from those who are truly comfortable taking it.

Respectfully,

– Michael

Michael, I thought you would be very interested in this article. Their findings are very similar to ours except that they use data from the Netherlands and are able to measure risk perception.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1717984

Know any affordable psychometric risk tolerance questionnaires out there, as an alternative to FinaMetrica?