Executive Summary

With the implementation date of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule looming large in April, all attention has been focused on how financial advisors and their Financial Institutions are making adjustments to manage their compensation conflicts of interest, to avoid breaching the fiduciary’s fundamental duty of loyalty to act in the client’s best interests.

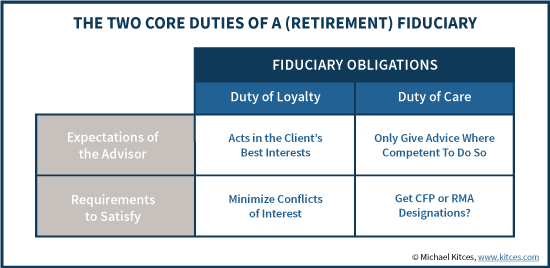

However, the reality is that being a fiduciary actually entails two core duties: the first is the duty of loyalty (to act in the client’s best interests), and the second is the duty of care (to provide diligent and prudent advice, and only in areas in which the advisor is competent to provide such advice). After all, a fiduciary obligation is relatively meaningless with only a duty of loyalty, if there’s no expectation of competency; otherwise, consumers would still be harmed by unwitting negligence, even if there was no intentional (or conflicted) self-enrichment.

And the distinction matters, because the Department of Labor’s Best Interests Contract Exemption attaches a fiduciary obligation to the Financial Institution itself, including the potential for a class action lawsuit against the institution for failing to meet its fiduciary obligations. Which means a Financial Institution could face a class action lawsuit not only for systemic breaches of the fiduciary duty of loyalty (e.g., by utilizing too much conflicted compensation), but also by systemically breaching the fiduciary duty of care but not sufficient training their advisors.

In other words, Financial Institutions face the risk that they will be sued in a class action lawsuit for failing to put their financial advisors through the training and education (e.g., professional designations) necessary to ensure that the advisor would even know what the “best” advice for the client was in the first place!

Unfortunately, right now there actually is no universally accepted minimum competency standard for financial advice (or in the case of DoL fiduciary, retirement advice), though certainly recognized rigorous designations that include both education and an advice process – such as the CFP Board’s CFP certification, and RIIA’s RMA designation – provide a likely path of safety for Financial Institutions. Which means in the coming year, there may soon be explosive growth in programs like the CFP and RMA, as Financial Institutions recognize and then try to minimize their exposure to a class action lawsuit for failing to meet the fiduciary duty of care.

The Two Core Duties Of A Fiduciary: Loyalty, And Care

The concept of a fiduciary duty spans more than just financial advice. The lawyer has a fiduciary duty to the client. A trustee has a fiduciary duty to the trust beneficiaries. A (corporate) board of directors has a fiduciary duty to the shareholders.

Although the exact application of fiduciary duties vary slightly based on context, they all typically entail two core duties.

The first is that a fiduciary owes a duty of loyalty (e.g., to clients, beneficiaries, or shareholders). The duty of loyalty is to serve the client first and foremost, rather than the fiduciary serving themselves; in other words, to act in their clients’ best interests. In the context of a fiduciary duty for financial advisors in particular, the ability to receive commissions presents the possibility that the advisor could be enriched at the expense of the client, rather than in his/her interests; as a result, advisors subject to a best interests standard are expected to disclose and minimize, or ideally avoid altogether, any conflicts of interest that could compromise the advisor’s ability to fulfill the duty of loyalty.

However, the reality is that there’s actually a second core duty that a fiduciary must fulfill as well: the duty of care. In essence, the duty of care requires that the fiduciary conduct appropriate due diligence, and make decisions in a prudent manner. Or viewed another way, the duty of care says that to serve as a fiduciary, you have to be competent enough to give fiduciary advice, and if not a core competency, to engage outside experts as necessary to substantiate that an appropriate best interests recommendation is being made.

Logically, the two duties actually should go hand in hand. After all, it makes little sense to require fiduciaries to exhibit a duty of loyalty to act in the best interests of the client, if the fiduciary doesn’t have the competency to know what’s in the client’s best interests in the first place. A fiduciary duty of loyalty without the associated duty of care would simply mean consumers are harmed by unwitting negligence rather than intentional (or conflicted) self-enrichment.

Which means, simply put, to actually deliver fiduciary recommendations the advisor must not only try to provide advice in the client’s best interests, but also ensure that he/she is competent enough to give that advice (or to appropriately vet and utilize experts who have the requisite expertise).

The Duty Of Care Under DoL Fiduciary

Recognizing that there are two core duties of a fiduciary – loyalty, and care – is not just an idle theoretical exercise. In the context of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, both are implicitly recognized in the requirements of the Best Interests Contract Exemption.

After all, the core requirement of the Best Interests Contract is that advisors must adhere to “Impartial Conduct Standards”, which stipulate that the advisor must give Best Interests advice, for Reasonable Compensation, and make no (materially) misleading statements.

In defining the specific expectations of the advisor’s advice, though, the Department of Labor states that:

"When providing investment advice to the Retirement Investor, the Financial Institution and the Adviser(s) provide investment advice that is, at the time of the recommendation, in the Best Interest of the Retirement Investor."

This statement, taken directly from the final rule, is a direct expression of both the Duty of Loyalty (that advice be in the Best Interests of the Retirement Investor), and also the Duty of Care (that the advice reflect the “care, skill, prudence, and diligence” that any other expert would have applied in a similar circumstance). Or viewed another way, if the advisor doesn’t have the knowledge and skills to be prudent and diligent, it’s not possible to fulfill the advisor’s fiduciary duty of care under the Department of Labor rules.

These dual fiduciary duties matter in the context of the Department of Labor’s rule in particular, because one of the key requirements of the Best Interests Contract Exemption is that Financial Institutions cannot exclusively limit consumers to mandatory arbitration in all circumstances. While any individual advisor/client incident can still be bound to arbitration, the DoL requires as a condition to qualify for the Best Interests Contract Exemption that consumers collectively still be allowed to sue the Financial Institution in a class action lawsuit.

Which means if a Financial Institution systemically violates its fiduciary obligation across the entire firm – either by not satisfying the duties of loyalty and care, and/or not overseeing and ensuring that the advisor meets those standards –it runs the risk of a very big class action lawsuit!

The Real Class Action Lawsuit That Looms Under DoL Fiduciary

Notably, the reality is that the compliance departments of many Financial Institutions have already been fretting the risk of a class action lawsuit. It’s one of the single most feared (or even loathed) provisions of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule for a large financial institution, because it dramatically raises the stakes of a potential systemic failure to fulfill the firm’s fiduciary duty to clients, outside the relative safety of one-advisor-at-a-time arbitration (especially industry-friendly FINRA arbitration).

On the other hand, thus far the focus of fulfilling the Financial Institution’s fiduciary obligation has been focused almost entirely on the duty of loyalty, from minimizing conflicts of interest by adjusting compensation grids and modifying recruiting contracts, to adjusting product shelves in an effort to eliminate differential compensation across products, and in some cases even choosing to pivot the entire Financial Institution to become a Level Fee fiduciary.

But this focus on managing exposure to potential fiduciary breaches of the duty of loyalty has completely missed that Financial Institutions are also exposed to failures in executing the fiduciary duty of care!

In other words, imagine what happens when a class action plaintiff’s attorney comes along to a mid-to-large-sized broker-dealer and says:

“Explain to me how your brokers would know what the “best interests” advice is for the client? What training and education have they had to establish the necessary technical competency, and what process were they trained in to ensure their advice reflects the care, skill, prudence, and diligence that a similar expert would have applied in a similar situation?”

For which the broker-dealer says… what?

“In order to deliver best-interests advice about a retiree’s life savings, we require our advisors to have a high school diploma*, and take a 3-hour regulatory exam (either the Series 6 or perhaps the Series 65)?

*But the high-school diploma is actually just optional.”

The unfortunate reality is that the standard FINRA regulatory exams do not actually provide the kind of training and education necessary to establish actual technical expertise (or even basic competency) regarding retirement advice. The Series 6 (or Series 7) are really just licensing exams to affirm that someone is legally allowed to sell various types of securities products; the Series 65 is designed primarily to ensure that investment advisers know the state and Federal laws that will apply to them. Neither train advisors in a process of evaluating client needs, nor provide them the technical competency to necessarily know which solution would be best in the first place.

Ironically, the Series 65 has been the minimum regulatory exam for Registered Investment Advisers for a long time, and RIAs have been subject to a fiduciary standard for a long time… and this disparity has been allowed to continue, despite the fact that the Series 65 doesn’t really provide much education to satisfy the fiduciary duty of care. However, from a practical perspective, any such breaches in the past would have still only been individual lawsuits with a particular advisor – and likely bound to arbitration. It’s only under the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule that the fiduciary duty is not just an obligation of the advisor but also the Financial Institution, and it’s only under the DoL rule (unlike the Investment Advisers Act) that fiduciary breaches must have the opportunity to escalate to class action status.

Which means, for the first time ever, Financial Institutions can be sued in a class action lawsuit for the lack of technical competency of their entire base of brokers. And with the DoL fiduciary rule effective date looming large in April of 2017, large broker-dealers may suddenly transition hundreds or even thousands of brokers into a new fiduciary obligation, all at once, with only perhaps some sales and product training, but not the training and education necessary to be capable of fulfilling their fiduciary duty of care!

What’s The Minimum Competency Standard For Financial Advice?

So given this dynamic, the question that arises for any Financial Institution facing DoL fiduciary implementation in April: what is an acceptable, defensible minimum competency standard to ensure a financial advisor is capable of giving best interests advice?

Notably, the key distinction here is not merely a question of raw technical knowledge alone. As a key part of the duty of care is not just “knowing stuff”, but having a process to substantiate that the fiduciary duty was executed appropriately. Accordingly, safe harbors of technical competency to meet the duty of care will likely be designation programs that teach not just the raw technical knowledge, but some kind of “advice process” as well.

For instance, CFP certification doesn’t just cover the breadth of its 72 principal knowledge topics; it also teaches the 6-step financial planning process as the core of its Financial Planning Practice Standards, to better substantiate that the advisor actually did his/her diligence in evaluating the client’s situation before making a prudent recommendation.

Arguably, an even more robust solution would be RIIA’s Retirement Management Analyst (RMA) designation, which also includes the use of its Retirement Procedural Prudence Map. The RIIA Procedural Prudence Map is the very essence of demonstrating the fiduciary advisor met his/her duty of care, with an in-depth process for validating why a particular retirement recommendation would be given (along with the supporting technical education to make the advisor competent enough to navigate the relevant decisions). This is an important distinction from even other retirement designations like the RICP or CRC, which don’t include the process tools that the RMA does.

In other words, it’s the combination of competency education, and a prudence process, that is necessary for an advisor to substantiate that he/she actually met the fiduciary duty of care (and not just the duty of loyalty).

At a minimum, though, the potential for a duty-of-care-based class action lawsuit could mean fresh scrutiny on the reams of lightweight or entirely “bogus” designations that still exist in the advisor marketplace, which appear to be on the decline with the rise of more credible designations (as there’s no reason to add a specious designation after getting a recognized one like CFP certification). As it stands, there are still surprisingly few designations that have ever been through any kind of stringent accreditation process (notable positive exceptions being IMCA’s CIMA certification with ANSI, and the CFP Board's accreditation with NCCA).

In other words, the issue of a designation’s credibility – especially given how many don’t have any accreditation or other means to substantiate and validate their program – will face greater scrutiny after DoL fiduciary, as Financial Institutions try to evaluate what will be a defensible designation to substantiate the advisor was trained enough to meet the Duty of Care. An advisor who is sufficiently trained and still fails to follow the process is the advisor’s fault; a Financial Institution that fails to train all of its advisors with a credible training program is a potential class action lawsuit.

The bottom line for Financial Institutions, though, is that while all eyes have been on the fiduciary duty of loyalty, arguably firms should also be taking an aggressive focus, now, on getting their advisors enrolled into a program that can actually substantiate that they are competent enough to give best-interests advice in the first place. Otherwise, the Financial Institutions may prevail in defending that their advisors meet the fiduciary duty of loyalty, but leave themselves a large class action lawsuit target for failing to meet the fiduciary duty of care.

Which, in turn, should be a substantial boon in the coming years to organizations like CFP Board, RIIA, and IMCA, which have focused for years on creating high-caliber designations, often accredited and/or backed by a legitimate advice process to substantiate the advisor’s due diligence (and further lifting their standards over time), which in a class action lawsuit could become enshrined as the recognized minimum standard for financial advisor competency (at least or especially when it comes to retirement advice) as financial planning slowly becomes the embodiment of fiduciary financial advice from the inside out.

So what do you think? Are too many firms focusing on the fiduciary duty of loyalty but ignoring the duty of care? What is the minimum competency standard for giving financial advice? Will DoL fiduciary be a boon for designations like the CFP and RMA? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!